<Back to Index>

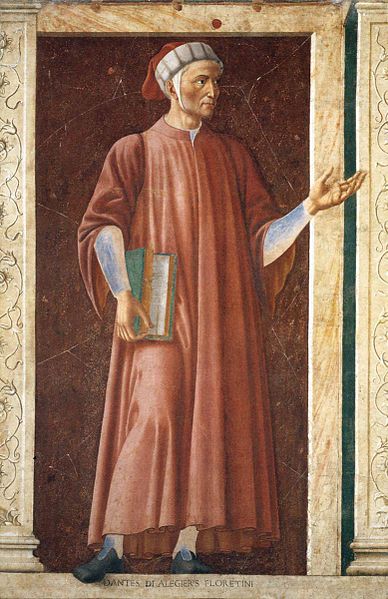

- Writer and Philosopher Durante degli Alighieri (Dante), 1265

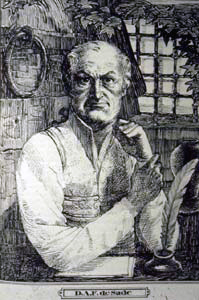

- Revolutionary Politician and Philosopher Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade, 1740

PAGE SPONSOR

Durante degli Alighieri, mononymously referred to as Dante (c.1265 – 1321), was an Italian poet, prose writer, literary theorist, moral philosopher and political thinker. He is best known for the monumental epic poem Commedia, later named La divina commedia (Divine Comedy), considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

In Italy he is known as il Sommo Poeta ("the Supreme Poet") or just il Poeta. Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio are also known as "the three fountains" or "the three crowns". Dante is also called the "Father of the Italian language".

Dante

was born in Florence, Italy. The exact date of Dante's

birth is unknown, although it is generally believed to be

around 1265. This can be deduced from autobiographic

allusions in La Divina

Commedia, "the Inferno" (Halfway through

the journey we are living, implying that Dante was

around 35 years old, as the average lifespan according to

the Bible (Psalms 89:10, Vulgate) is 70 years; and as the

imaginary travel took place in 1300, Dante must have been

born around 1265). Some verses of the Paradiso

section of the Divine Comedy also provide a

possible clue that he was born under the sign of Gemini:

"As I revolved with the eternal twins, I saw revealed from

hills to river outlets, the threshing - floor that makes

us so ferocious" (XXII 151 - 154). In 1265 the Sun was in

Gemini approximately during the period of May 11 to June

11.

Dante claimed that his family descended from the ancient Romans (Inferno, XV, 76), but the earliest relative he could mention by name was Cacciaguida degli Elisei (Paradiso, XV, 135), of no earlier than about 1100. Dante's father, Alaghiero or Alighiero di Bellincione, was a White Guelph who suffered no reprisals after the Ghibellines won the Battle of Montaperti in the middle of the 13th century. This suggests that Alighiero or his family enjoyed some protective prestige and status, although some suggest that the politically inactive Alighiero was of such low standing that he was not considered worth exiling.

Dante's family had loyalties to the Guelphs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy and which was involved in complex opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor. The poet's mother was Bella, likely a member of the Abati family. She died when Dante was not yet ten years old, and Alighiero soon married again, to Lapa di Chiarissimo Cialuffi. It is uncertain whether he really married her, as widowers had social limitations in these matters, but this woman definitely bore two children, Dante's half - brother Francesco and half - sister Tana (Gaetana). When Dante was 12, he was promised in marriage to Gemma di Manetto Donati, daughter of Manetto Donati, member of the powerful Donati family. Contracting marriages at this early age was quite common and involved a formal ceremony, including contracts signed before a notary. Dante had by this time fallen in love with another, Beatrice Portinari (known also as Bice), whom he first met when he was nine years old. Years after his marriage to Gemma, he claims to have met Beatrice again; although he wrote several sonnets to Beatrice, he never mentioned his wife Gemma in any of his poems. The exact date of his marriage is not known: the only certain information is that, before his exile in 1301, Dante already had three children (Pietro, Jacopo and Antonia).

Dante fought with the Guelph cavalry at the Battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289). This victory brought about a reformation of the Florentine constitution. To take any part in public life, one had to be enrolled in one of the city's many commercial or artisan guilds, so Dante entered the guild of physicians and apothecaries. In the following years, his name is occasionally found recorded as speaking or voting in the various councils of the republic. A substantial portion of minutes from such meetings from 1298 - 1300 were lost during World War II, however; consequently the true extent of Dante's participation in the city's councils is uncertain.

Dante had several children with Gemma. Several people subsequently claimed to be Dante's offspring; however, it is likely that Jacopo, Pietro, Giovanni and Antonia were truly his children. Antonia later became a nun with the name of Sister Beatrice.

Not much is known about Dante's education, and it is

presumed he studied at home or in a chapter school

attached to a church or monastery in Florence. It is known

that he studied Tuscan poetry, at a time when the Sicilian

School (Scuola poetica Siciliana), a cultural group

from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. His interests

brought him to discover the Provençal

poetry of the troubadours

and the Latin writers of classical antiquity, including

Cicero, Ovid, and especially Virgil.

Dante says that he first met Beatrice Portinari, daughter of Folco Portinari, at age nine, and he claims to have fallen in love "at first sight", apparently without even speaking to her. He saw her frequently after age 18, often exchanging greetings in the street, but he never knew her well; in effect, he set an example of so-called courtly love, a phenomenon developed in French and Provençal poetry of the preceding centuries. Dante's experience of such love was typical, but his expression of it was unique. It was in the name of this love that Dante gave his imprint to the Dolce Stil Novo (Sweet New Style, a term which Dante himself coined), and he would join other contemporary poets and writers in exploring the themes of Love (Amore), which had never been so emphasized before. Love for Beatrice (as in a different manner Petrarch would show for his Laura) would be his reason for poetry and for living, together with political passions. In many of his poems, she is depicted as semi - divine, watching over him constantly and providing spiritual instruction, sometimes harshly. When Beatrice died in 1290, Dante sought refuge in Latin literature. The Convivio reveals that he had read Boethius's De consolatione philosophiae and Cicero's De Amicitia. He then dedicated himself to philosophical studies at religious schools like the Dominican one in Santa Maria Novella. He took part in the disputes that the two principal mendicant orders (Franciscan and Dominican) publicly or indirectly held in Florence, the former explaining the doctrine of the mystics and of Saint Bonaventure, the latter presenting Saint Thomas Aquinas' theories.

At 18, Dante met Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Cino da Pistoia and soon after Brunetto Latini; together they became the leaders of the Dolce Stil Novo. Brunetto later received a special mention in the Divine Comedy (Inferno, XV, 28), for what he had taught Dante. Nor speaking less on that account, I go With Ser Brunetto, and I ask who are His most known and most eminent companions. Some fifty poetical components by Dante are known (the so-called Rime, rhymes), others being included in the later Vita Nuova and Convivio. Other studies are reported, or deduced from Vita Nuova or the Comedy, regarding painting and music.

Dante, like most Florentines of his day, was embroiled in the Guelph - Ghibelline conflict. He fought in the Battle of Campaldino (June 11, 1289), with the Florentine Guelphs against Arezzo Ghibellines; then in 1294 he was among the escorts of Charles Martel of Anjou (grandson of Charles I of Naples, more commonly called Charles of Anjou) while he was in Florence. To further his political career, he became a pharmacist. He did not intend to practice as one, but a law issued in 1295 required that nobles who wanted public office had to be enrolled in one of the Corporazioni delle Arti e dei Mestieri, so Dante obtained admission to the apothecaries' guild. This profession was not inappropriate, since at that time books were sold from apothecaries' shops. As a politician, he accomplished little, but he held various offices over a number of years in a city undergoing political unrest.

After defeating the Ghibellines, the Guelphs divided into two factions: the White Guelphs (Guelfi Bianchi) — Dante's party, led by Vieri dei Cerchi — and the Black Guelphs (Guelfi Neri), led by Corso Donati. Although initially the split was along family lines, ideological differences arose based on opposing views of the papal role in Florentine affairs, with the Blacks supporting the Pope and the Whites wanting more freedom from Rome. Initially the Whites were in power, and they expelled the Blacks. In response, Pope Boniface VIII planned a military occupation of Florence. In 1301, Charles of Valois, brother of King Philip IV of France, was expected to visit Florence because the Pope had appointed him peacemaker for Tuscany. But the city's government had treated the Pope's ambassadors badly a few weeks before, seeking independence from papal influence. It was believed that Charles of Valois had received other unofficial instructions, so the council sent a delegation to Rome to ascertain the Pope's intentions. Dante was one of the delegates.

Pope Boniface quickly dismissed the other delegates and asked Dante alone to remain in Rome. At the same time (November 1, 1301), Charles of Valois entered Florence with the Black Guelphs, who in the next six days destroyed much of the city and killed many of their enemies. A new Black Guelph government was installed and Cante de' Gabrielli da Gubbio was appointed podestà of the city. Dante was condemned to exile for two years and ordered to pay a large fine. The poet was still in Rome where the Pope had "suggested" he stay; Dante was therefore considered an absconder. He did not pay the fine in part because he believed he was not guilty and in part because all his assets in Florence had been seized by the Black Guelphs. He was condemned to perpetual exile, and if he returned to Florence without paying the fine, he could be burned at the stake. (The city council of Florence finally passed a motion rescinding Dante's sentence in June 2008.)

He took part in several attempts by the White Guelphs to

regain power, but these failed due to treachery. Dante,

bitter at the treatment he received from his enemies, also

grew disgusted with the infighting and ineffectiveness of

his erstwhile allies and vowed to become a party of one.

Dante went to Verona as

a guest of Bartolomeo I della Scala, then moved to Sarzana

in Liguria. Later, he is supposed to have lived in Lucca

with a lady called Gentucca, who made his stay comfortable

(and was later gratefully mentioned in Purgatorio,

XXIV, 37). Some speculative sources claim he visited Paris

between 1308 and 1310 and others, even less trustworthy,

take him to Oxford: these claims, first occurring in Boccaccio's book on Dante

several decades after his death, seem inspired by readers

being impressed with the poet's wide learning and

erudition. Evidently Dante's command of philosophy and his

literary interests deepened in exile, when he was no

longer busy with the day - to - day business of Florentine

domestic politics, and this is evidenced in his prose

writings in this period, but there is no real indication

that he ever left Italy. Dante's Immensa Dei dilectione

testante to Henry VII of Luxembourg confirms his

residence "beneath the springs of Arno, near Tuscany" in

March 1311. In 1310, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of

Luxembourg marched 5,000 troops into Italy. Dante saw in

him a new Charlemagne who would restore the office of the

Holy Roman Emperor to its former glory and also re-take

Florence from the Black Guelphs. He wrote to Henry and

several Italian princes, demanding that they destroy the

Black Guelphs. Mixing religion and private concerns, he

invoked the worst anger of God against his city and

suggested several particular targets that were also his

personal enemies. It was during this time that he wrote De

Monarchia, proposing a universal monarchy under

Henry VII.

At some point during his exile, he conceived of the Comedy, but the date is uncertain. The work is much more assured and on a larger scale than anything he had produced in Florence; it is likely that he would have undertaken such a work only after he realized that his political ambitions, which had been central to him up to his banishment, had been halted for some time, possibly forever. It is also noticeable that Beatrice has returned to his imagination with renewed force and with a wider meaning than in the Vita Nuova; in Convivio (written c.1304 - 07) he had declared that the memory of this youthful romance belonged to the past. One of the earliest outside indications that the poem was under way is a notice by the law professor Francesco da Barberino, tucked into his I Documenti d'Amore (Lessons of Love) and written probably in 1314 or early 1315: speaking of Virgil, da Barberino notes in appreciative words that Dante followed the Roman classic in a poem called the Comedy, and that the setting of this poem (or part of it) was the underworld, that is, Hell. The brief note gives no incontestable indication that he himself had seen or read even Inferno, or that this part had been published at the time, but it indicates that composition was well under way and that the sketching of the poem may likely have begun some years before. We know that Inferno had been published by 1317; this is established by quoted lines interspersed in the margins of contemporary dated records from Bologna, but there is no certainty whether the three parts of the poem were published each part in full or a few cantos at a time. Paradiso seems to have been published posthumously.

In Florence, Baldo d'Aguglione pardoned most of the White Guelphs in exile and allowed them to return; however, Dante had gone too far in his violent letters to Arrigo (Henry VII), and the sentence on him was not recalled.

In 1312, Henry assaulted Florence and defeated the Black Guelphs, but there is no evidence that Dante was involved. Some say he refused to participate in the assault on his city by a foreigner; others suggest that he had become unpopular with the White Guelphs, too, and that any trace of his passage had carefully been removed. In 1313, Henry VII died (from fever), and with him any hope for Dante to see Florence again. He returned to Verona, where Cangrande I della Scala allowed him to live in a certain security and, presumably, in a fair amount of prosperity. Cangrande was admitted to Dante's Paradise (Paradiso, XVII, 76).

In 1315, Florence was forced by Uguccione della Faggiuola

(the military officer controlling the town) to grant an

amnesty to people in exile, including Dante. But Florence

required that, as well as paying a steep sum of money,

these exiles would do public penance. Dante refused,

preferring to remain in exile. When Uguccione defeated

Florence, Dante's death sentence was commuted to house

arrest, on condition that he go to Florence to swear that

he would never enter the town again. Dante refused to go.

His death sentence was confirmed and extended to his sons.

Dante still hoped late in life that he might be invited

back to Florence on honorable terms. For Dante, exile was

nearly a form of death, stripping him of much of his

identity and his heritage. He addresses the pain of exile

in Paradiso, XVII (55 - 60), where Cacciaguida,

his great - great - grandfather, warns him what to expect:

| ... Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta | ... You shall leave everything you love most: |

| più caramente; e questo è quello strale | this is the arrow that the bow of exile |

| che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta. | shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste |

| Tu proverai sì come sa di sale | of others' bread, how salty it is, and know |

| lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle | how hard a path it is for one who goes |

| lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale ... | ascending and descending others' stairs ... |

As for the hope of returning to Florence, he describes it as if he had already accepted its impossibility, (Paradiso, XXV, 1–9):

| Se mai continga che 'l poema sacro | If it ever come to pass that the sacred poem |

| al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra, | to which both heaven and earth have set their hand |

| sì che m'ha fatto per molti anni macro, | so as to have made me lean for many years |

| vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra | should overcome the cruelty that bars me |

| del bello ovile ov'io dormi' agnello, | from the fair sheepfold where I slept as a lamb, |

| nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra; | an enemy to the wolves that make war on it, |

| con altra voce omai, con altro vello | with another voice now and other fleece |

| ritornerò poeta, e in sul fonte | I shall return a poet and at the font |

| del mio battesmo prenderò 'l cappello ... | of my baptism take the laurel crown ... |

Prince Guido Novello da

Polenta invited him to Ravenna in 1318, and he

accepted. He finished the Paradiso, and died in

1321 (at the age of 56) while returning to Ravenna from a

diplomatic mission to Venice, possibly of malaria

contracted there. Dante was buried in Ravenna at the

Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called San Francesco).

Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice, built a tomb in 1483.

On the grave, some verses of Bernardo Canaccio, a friend of Dante, dedicated to Florence:

- parvi Florentia mater amoris

- "Florence, mother of little love"

The first formal biography of Dante was the Vita di Dante (also known as Trattatello in laude di Dante) written after 1348 by Giovanni Boccaccio; several statements and episodes of it are seen as unreliable by modern research. However, an earlier account of Dante's life and works had been included in the Nuova Cronica of the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani.

Eventually, Florence came to regret Dante's exile, and the city made repeated requests for the return of his remains. The custodians of the body at Ravenna refused, at one point going so far as to conceal the bones in a false wall of the monastery. Nevertheless, in 1829, a tomb was built for him in Florence in the basilica of Santa Croce. That tomb has been empty ever since, with Dante's body remaining in Ravenna, far from the land he loved so dearly. The front of his tomb in Florence reads Onorate l'altissimo poeta — which roughly translates as "Honor the most exalted poet". The phrase is a quote from the fourth canto of the Inferno, depicting Virgil's welcome as he returns among the great ancient poets spending eternity in Limbo. The continuation of the line, L'ombra sua torna, ch'era dipartita ("his spirit, which had left us, returns"), is poignantly absent from the empty tomb.

In 2007, a reconstruction of Dante's face was completed in a collaborative project. Artists from Pisa University and engineers at the University of Bologna at Forli completed the revealing model, which indicated that Dante's features were somewhat different from what was once thought.

The

Divine Comedy describes Dante's journey through

Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and

Paradise (Paradiso), guided first by the Roman poet

Virgil and then by Beatrice, the subject of his love and

of another of his works, La Vita Nuova. While the

vision of Hell, the Inferno, is vivid for modern

readers, the theological niceties presented in the other

books require a certain amount of patience and knowledge

to appreciate. Purgatorio, the most lyrical and

human of the three, also has the most poets in it; Paradiso,

the most heavily theological, has the most beautiful and

ecstatic mystic passages in which Dante tries to describe

what he confesses he is unable to convey (e.g., when Dante

looks into the face of God: "all'alta fantasia qui mancò

possa" — "at this high moment, ability failed my capacity

to describe," Paradiso, XXXIII, 142).

By its serious purpose, its literary stature and the range — both stylistically and in subject matter — of its content, the Comedy soon became a cornerstone in the evolution of Italian as an established literary language. Dante was more aware than most earlier Italian writers of the variety of Italian dialects and of the need to create a literature beyond the limits of Latin writing at the time, and a unified literary language; in that sense he is a forerunner of the renaissance with its effort to create vernacular literature in competition with earlier classical writers. Dante's in - depth knowledge (within the realms of the time) of Roman antiquity and his evident admiration for some aspects of pagan Rome also point forward to the 15th century. Ironically, while he was widely honored in the centuries after his death, the Comedy slipped out of fashion among men of letters: too medieval, too rough and tragical and not stylistically refined in the respects that the high and late renaissance came to demand of literature.

He wrote the Comedy in a language he called "Italian", in some sense an amalgamated literary language mostly based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, with some elements of Latin and of the other regional dialects. The aim was to deliberately reach a readership throughout Italy, both laymen, clergymen and other poets. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression. In French, Italian is sometimes nicknamed la langue de Dante. Publishing in the vernacular language marked Dante as one of the first (among others such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio) to break free from standards of publishing in only Latin (the language of liturgy, history, and scholarship in general, but often also of lyric poetry). This break set a precedent and allowed more literature to be published for a wider audience — setting the stage for greater levels of literacy in the future. However, unlike Boccaccio, Milton or Ariosto, Dante did not really become an author read all over Europe until the romantic era. To the romantics, Dante, like Homer and Shakespeare, was a prime example of the "original genius" who sets his own rules, creates persons of overpowering stature and depth and goes far beyond any imitation of the patterns of earlier masters and who, in turn, cannot really be imitated. Throughout the 19th century, Dante's reputation grew and solidified, and by the time of the 1865 jubilee, he had become solidly established as one of the greatest literary icons of the Western world.

Readers often cannot understand how such a serious work may be called a "comedy". In Dante's time, all serious scholarly works were written in Latin (a tradition that would persist for several hundred years more, until the waning years of the Enlightenment) and works written in any other language were assumed to be more trivial in nature. Furthermore, the word "comedy" in the classical sense refers to works which reflect belief in an ordered universe, in which events not only tended towards a happy or "amusing" ending, but an ending influenced by a Providential will that orders all things to an ultimate good. By this meaning of the word, as Dante himself wrote in a letter to Cangrande I della Scala, the progression of the pilgrimage from Hell to Paradise is the paradigmatic expression of comedy, since the work begins with the pilgrim's moral confusion and ends with the vision of God.

Dante's other works include the Convivio ("The

Banquet") a collection of his longest poems with an

(unfinished) allegorical commentary; Monarchia, a

summary treatise of political philosophy in Latin, which

was condemned and burned after Dante's death by the Papal

Legate Bertrando del Poggetto,

which argues for the necessity of a universal or global

monarchy in order to establish universal peace in this

life, and this monarchy's relationship to the Roman Catholic Church as

guide to eternal peace; De vulgari eloquentia ("On

the Eloquence of Vernacular"), on vernacular literature,

partly inspired by the Razos de trobar of Raimon

Vidal de Bezaudun; and, La Vita Nuova ("The New

Life"), the story of his love for Beatrice Portinari, who

also served as the ultimate symbol of salvation in the Comedy.

The Vita Nuova contains many of Dante's love poems

in Tuscan, which was not unprecedented; the vernacular had

been regularly used for lyric works before, during all the

thirteenth century. One of the most famous poems is Tanto

gentile e tanto onesta pare, which many Italians can

recite by heart. However, Dante's commentary on his own

work is also in the vernacular — both in the Vita

Nuova and in the Convivio — instead of the

Latin that was almost universally used. References to Divina

Commedia are in the format (book, canto, verse),

e.g., (Inferno, XV, 76).

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814) was a French aristocrat, revolutionary politician, philosopher, and writer famous for his libertine sexuality and lifestyle. His works include novels, short stories, plays, dialogues and political tracts; in his lifetime some were published under his own name, while others appeared anonymously and Sade denied being their author. He is best known for his erotic works, which combined philosophical discourse with pornography, depicting sexual fantasies with an emphasis on violence, criminality and blasphemy against the Catholic Church. He was a proponent of extreme freedom, unrestrained by morality, religion or law.

Sade was incarcerated in various prisons and in an insane asylum for about 32 years of his life; 11 years in Paris (10 of which were spent in the Bastille), a month in the Conciergerie, two years in a fortress, a year in Madelonnettes, three years in Bicêtre, a year in Sainte - Pélagie, and 13 years in the Charenton asylum. During the French Revolution he was an elected delegate to the National Convention. Many of his works were written in prison.

The Marquis de Sade was born in the Condé palace, Paris, to Comte

Jean - Baptiste François Joseph de Sade and Marie -

Eléonore de Maillé de Carman, cousin and Lady - in -

waiting to the Princess of Condé. He was educated by an

uncle, the Abbé de Sade. Later, he attended a Jesuit lycée, then pursued a

military career, becoming Colonel of a Dragoon regiment,

and fighting in the Seven Years' War. In 1763, on

returning from war, he courted a rich magistrate's

daughter, but her father rejected his suit and, instead,

arranged a marriage with his elder daughter, Renée -

Pélagie de Montreuil; that marriage produced two sons and

a daughter. In 1766, he had a private theater built in his

castle, the Château de Lacoste, in Provence. In January

1767, his own father died.

The Sade men alternated using the marquis and comte (count) titles. His grandfather, Gaspard François de Sade, was the first to use marquis; occasionally, he was the Marquis de Sade, but is documentarily identified as the Marquis de Mazan. The Sade family were Noblesse d'épée, claiming at the time the oldest, Frank descended nobility, so, assuming a noble title without a King's grant, was customarily de rigueur. Alternating title usage indicates that titular hierarchy (below duc et pair) was notional; theoretically, the marquis title was granted to noblemen owning several countships, but its use by men of dubious lineage caused its disrepute. At Court, precedence was by seniority and royal favor, not title. There is father - and - son correspondence, wherein father addresses son as marquis.

For many years, Sade's descendants regarded his life and

work as a scandal to be suppressed. This did not change

until the mid twentieth century, when the Comte Xavier de

Sade reclaimed the marquis title, long fallen into disuse,

on his visiting cards, and took an interest in his

ancestor's writings. At that time, the "Divine Marquis" of

legend was so unmentionable in his own family that Xavier

de Sade only learned of him in the late 1940s when

approached by a journalist. He subsequently

discovered a store of Sade's papers in the family château

at Condé - en - Brie, and worked with scholars for decades

to enable their publication. His youngest son, the Marquis

Thibault de Sade, has continued such collaboration. The

family have also claimed copyright of the name. The

Château de Condé was sold by the family in 1983. As well

as the manuscripts they retain, others are held in

universities and libraries. Many, however, were lost in

the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A substantial

amount were destroyed after Sade's death at the

instigation of his son, Donatien - Claude - Armand.

Sade lived a scandalous libertine existence and repeatedly procured young prostitutes as well as employees of both sexes in his castle in Lacoste. He was also accused of blasphemy, a serious offense at that time. His behavior included an affair with his wife's sister, Anne - Prospère, who had come to live at the castle.

Beginning in 1763, Sade lived mainly in or near Paris. Several prostitutes there complained about mistreatment by him and he was put under surveillance by the police, who made detailed reports of his activities. After several short imprisonments, which included a brief incarceration in the Château de Saumur (then a prison), he was exiled to his château at Lacoste in 1768.

The first major scandal occurred on Easter Sunday in 1768, in which Sade procured the sexual services of a woman, Rose Keller; whether she was a prostitute or not is widely disputed. He was accused of taking her to his chateau at Arcueil, imprisoning her there and sexually and physically abusing her. She escaped by climbing out of a second floor window and running away. At this time, la Présidente, Sade's mother - in - law, obtained a lettre de cachet (a royal order of arrest and imprisonment, without stated cause or access to the courts) from the king, excluding Sade from the jurisdiction of the courts. The lettre de cachet would later prove disastrous for the marquis.

A 1772 episode in Marseille involved the non - lethal poisoning of prostitutes with the supposed aphrodisiac Spanish fly and sodomy with his manservant Latour. That year, the two men were sentenced to death in absentia for sodomy and said poisoning. They fled to Italy, and Sade took his wife's sister with him.

Sade and Latour were caught and imprisoned at the Fortress of Miolans in late 1772, but escaped four months later.

Sade later hid at Lacoste, where he rejoined his wife, who became an accomplice in his subsequent endeavors. He kept a group of young employees at Lacoste, most of whom complained about sexual mistreatment and quickly left his service. Sade was forced to flee to Italy once again. It was during this time he wrote Voyage d'Italie, which, along with his earlier travel writings, has never been translated into English. In 1776, he returned to Lacoste, again hired several servant girls, most of whom fled. In 1777, the father of one of those employees went to Lacoste to claim his daughter, and attempted to shoot the Marquis at point blank range, but the gun misfired.

Later that year, Sade was tricked into going to Paris to visit his supposedly ill mother, who in fact had recently died. He was arrested there and imprisoned in the Château de Vincennes. He successfully appealed his death sentence in 1778, but remained imprisoned under the lettre de cachet. He escaped but was soon recaptured. He resumed writing and met fellow prisoner Comte de Mirabeau, who also wrote erotic works. Despite this common interest, the two came to dislike each other immensely.

In 1784, Vincennes was closed and Sade was transferred to the Bastille. On 2 July 1789, he reportedly shouted out from his cell to the crowd outside, "They are killing the prisoners here!", causing something of a riot. Two days later, he was transferred to the insane asylum at Charenton near Paris (the storming of the Bastille, a major event of the French Revolution, occurred on 14 July).

He had been working on his magnum opus Les 120 Journées de Sodome (The 120 Days of Sodom). To his despair, he believed that the manuscript was lost during his transfer; but he continued to write.

He was released from Charenton in 1790, after the new

Constituent Assembly abolished the instrument of lettre

de cachet. His wife obtained a divorce soon after.

During Sade's time of freedom, beginning in 1790, he published several of his books anonymously. He met Marie - Constance Quesnet, a former actress, and mother of a six year old son, who had been abandoned by her husband. Constance and Sade would stay together for the rest of his life.

He initially ingratiated himself with the new political situation after the revolution, supported the Republic, called himself "Citizen Sade" and managed to obtain several official positions despite his aristocratic background.

Due to the damage done to his estate in Lacoste, which was sacked in 1789 by an angry mob, he moved to Paris. In 1790, he was elected to the National Convention, where he represented the far left. He was a member of the Piques section, notorious for its radical views. He wrote several political pamphlets, in which he called for the implementation of direct vote. However, there is much to suggest that he suffered abuse from his fellow revolutionaries due to his aristocratic background. Matters were not helped by his son's May 1792 desertion from the military, where he had been serving as a second lieutenant and the aide - de - camp to an important colonel, the Marquis de Toulengeon. De Sade was forced to disavow his son's desertion in order to save his neck. Later that year, his name was added – whether by error or willful malice – to the list of émigrés of the Bouches - du - Rhône department.

Despite being appalled by the Reign of Terror in 1793, he wrote an admiring eulogy for Jean - Paul Marat. At this stage, he was becoming publicly critical of Maximilien Robespierre, and on 5 December, he was removed from his posts, accused of "moderatism" and imprisoned for almost a year. This experience presumably confirmed his life long detestation of state tyranny and especially of the death penalty. He was released in 1794, after the overthrow and execution of Robespierre had effectively ended the Reign of Terror.

In 1796, now all but destitute, he had to sell his ruined

castle in Lacoste.

In 1801 Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the anonymous author of Justine and Juliette. Sade was arrested at his publisher's office and imprisoned without trial; first in the Sainte - Pélagie prison and, following allegations that he had tried to seduce young fellow prisoners there, in the harsh fortress of Bicêtre.

After intervention by his family, he was declared insane in 1803 and transferred once more to the asylum at Charenton. His ex-wife and children had agreed to pay his pension there. Constance was allowed to live with him at Charenton. The benign director of the institution, Abbé de Coulmier, allowed and encouraged him to stage several of his plays, with the inmates as actors, to be viewed by the Parisian public. Coulmier's novel approaches to psychotherapy attracted much opposition. In 1809, new police orders put Sade into solitary confinement and deprived him of pens and paper, though Coulmier succeeded in ameliorating this harsh treatment. In 1813, the government ordered Coulmier to suspend all theatrical performances.

Sade began a sexual relationship with 13 year old Madeleine Leclerc, daughter of an employee at Charenton. This affair lasted some 4 years, until Sade's death in 1814.

He had left instructions in his will forbidding that his body

be opened for any reason whatsoever, and that it remain

untouched for 48 hours in the chamber in which he died,

and then placed in a coffin and buried on his property

located in Malmaison near Épernon. His skull was later

removed from the grave for phrenological examination. His

son had all his remaining unpublished manuscripts burned,

including the immense multi - volume work Les Journées de Florbelle.

Numerous writers and artists, especially those concerned with sexuality, have been both repelled and fascinated by Sade.

The contemporary rival pornographer Rétif de la Bretonne published an Anti - Justine in 1798.

Geoffrey Gorer, an English anthropologist and author (1905 – 1985), wrote one of the earliest books on Sade entitled The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade in 1935. He pointed out that Sade was in complete opposition to contemporary philosophers for both his "complete and continual denial of the right to property" (particularly evident in his advocacy of a utopian socialist society in Aline and Valcour and Yet Another Effort, Frenchmen, If You Would Become Republicans), and for viewing the struggle in late 18th century French society as being not between "the Crown, the bourgeoisie, the aristocracy or the clergy, or sectional interests of any of these against one another," but rather all of these "more or less united against the proletariat." By holding these views, he cut himself off entirely from the revolutionary thinkers of his time to join those of the mid nineteenth century. Thus, Gorer argued, "he can with some justice be called the first reasoned socialist."

Simone de Beauvoir (in her essay Must we burn Sade?, published in Les Temps modernes, December 1951 and January 1952) and other writers have attempted to locate traces of a radical philosophy of freedom in Sade's writings, preceding modern existentialism by some 150 years. He has also been seen as a precursor of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis in his focus on sexuality as a motive force. The surrealists admired him as one of their forerunners, and Guillaume Apollinaire famously called him "the freest spirit that has yet existed".

Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 book Sade Mon Prochain ("Sade My Neighbor"), analyzes Sade's philosophy as a precursor of nihilism, negating Christian values and the materialism of the Enlightenment.

One of the essays in Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) is titled "Juliette or Enlightenment and Morality" and interprets the ruthless and calculating behavior of Juliette as the embodiment of the philosophy of enlightenment. Similarly, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan posited in his 1966 essay "Kant avec Sade" that de Sade's ethics was the complementary completion of the categorical imperative originally formulated by Immanuel Kant. However, at least one philosopher has rejected Adorno and Horkheimer’s claim that Sade’s moral skepticism is actually coherent, or that it reflects Enlightenment thought.

In his 1988 Political Theory and Modernity, William E. Connolly analyzes Sade's Philosophy in the Bedroom as an argument against earlier political philosophers, notably Rousseau and Hobbes, and their attempts to reconcile nature, reason and virtue as basis of ordered society. Similarly, Camille Paglia argued that Sade can be best understood as a satirist, responding "point by point" to Rousseau's claims that society inhibits and corrupts mankind's innate goodness: Sade wrote in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when Rousseauist Jacobins instituted the bloody Reign of Terror.

In The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography (1979), Angela Carter provides a feminist reading of Sade, seeing him as a "moral pornographer" who creates spaces for women. Similarly, Susan Sontag defended both Sade and Georges Bataille's Histoire de l'oeil (Story of the Eye) in her essay "The Pornographic Imagination" (1967) on the basis their works were transgressive texts, and argued that neither should be censored. By contrast, Andrea Dworkin saw Sade as the exemplary woman hating pornographer, supporting her theory that pornography inevitably leads to violence against women. One chapter of her book Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1979) is devoted to an analysis of Sade. Susie Bright claims that Dworkin's first novel Ice and Fire, which is rife with violence and abuse, can be seen as a modern retelling of Sade's Juliette.

Ian

Brady, who with Myra Hindley carried out torture and

murder of children known as the Moors murders in England

during the 1960s, was fascinated by Sade, and the

suggestion was made at their trial and appeals that the

tortures (some of which they tape recorded) were

influenced by Sade's ideas and fantasies.

Brady and Hindley had, however, read very little of Sade's

actual work; the only book of his they possessed was an

anthology of excerpts that included none of his most

extreme writings.

There have been many and varied references to the Marquis de Sade in popular culture, including fictional works and biographies. The eponym of the psychological and subcultural term sadism, his name is used variously to evoke sexual violence, licentiousness and freedom of speech. In modern culture his works are simultaneously viewed as masterful analyses of how power and economics work, and as erotica. Sade's sexually explicit works were a medium for the articulation of the corrupt and hypocritical values of the elite in his society, which caused him to become imprisoned. He thus became a symbol of the artist's struggle with the censor. Sade's use of pornographic devices to create provocative works that subvert the prevailing moral values of his time inspired many other artists in a variety of media. The cruelties depicted in his works gave rise to the concept of sadism. Sade's works have to this day been kept alive by artists and intellectuals because they espouse a philosophy of extreme individualism that became reality in the economic liberalism of the following centuries.

In the late 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in Sade; leading French intellectuals like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault published studies of the philosopher, and interest in Sade among scholars and artists continued. In the realm of visual arts, many surrealist artists had interest in the Marquis. Sade was celebrated in surrealist periodicals, and feted by figures such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard and Maurice Heine; Man Ray admired Sade because he and other surrealists viewed him as an ideal of freedom. The first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) announced that "Sade is surrealist in sadism", and extracts of the original draft of Justine were published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution. In literature, Sade is referenced in several stories by horror and science fiction writer (and author of Psycho) Robert Bloch, while Polish science fiction author Stanisław Lem wrote an essay analyzing the game theory arguments appearing in Sade's Justine. The writer Georges Bataille applied Sade's methods of writing about sexual transgression to shock and provoke readers.

Sade's life and works have been the subject of numerous fictional plays, films, pornographic or erotic drawings, etchings and more. These include Peter Weiss's play Marat / Sade, a fantasia extrapolating from the fact that Sade directed plays performed by his fellow inmates at the Charenton asylum. Yukio Mishima, Barry Yzereef, and Doug Wright also wrote plays about Sade; Weiss's and Wright's plays have been made into films. His work is referenced on film at least as early as Luis Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (1930), the final segment of which provides a coda to Sade's 120 Days of Sodom, with the four debauched noblemen emerging from their mountain retreat. Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), updating Sade's novel to the brief Salo Republic; Benoît Jacquot's Sade and Philip Kaufman's Quills (from the play of the same name by Doug Wright) both hit cinemas in 2000. Quills, inspired by Sade's imprisonment and battles with the censorship in his society, portrays Sade as a literary freedom fighter who is a martyr to the cause of free expression.

Oftentimes Sade himself has been depicted in American

popular culture less as a revolutionary or even as a

libertine and more akin to as a sadistic and tyrannical

villain. For example, in the final episode of the

television series, Friday the 13th: The Series,

Miki, the female protagonist, travels back in time and

ends up being imprisoned and tortured by Sade. Similarly,

in the horror film, Waxwork, Sade is among the

film's wax villains to come alive.

The Marquis de Sade viewed Gothic fiction as a genre that relied heavily on magic and phantasmagoria. In his literary criticism Sade sought to prevent his fiction from being labeled ‘Gothic’ by emphasizing Gothic's supernatural aspects as the fundamental difference from themes in his own work. But while he sought this separation he believed the Gothic played a necessary role in society and discussed its roots and its uses. He wrote that the Gothic novel was a perfectly natural, predictable consequence of the revolutionary sentiments in Europe. He theorized that the adversity of the period had rightfully caused Gothic writers to "look to hell for help in composing their alluring novels." Sade held the work of writers Matthew Lewis and Ann Radcliffe high above other Gothic authors, praising the brilliant imagination of Radcliffe and pointing to Lewis' The Monk as without question the genre’s best achievement. Sade nevertheless believed that the genre was at odds with itself, arguing that the supernatural elements within Gothic fiction created an inescapable dilemma for both its author and its readers. He argued that an author in this genre was forced to choose between elaborate explanations of the supernatural or no explanations at all and that in either case the reader was unavoidably rendered incredulous. Despite his celebration of The Monk, Sade believed that there was not a single Gothic novel that had been able to overcome these problems. He theorized that if these problems were successfully avoided within the genre that the resulting work would be universally regarded for its excellence in fiction.

Many assume that Sade's criticism of the Gothic novel is

a reflection of his frustration with sweeping

interpretations of works like Justine. Within his

objections to the lack of verisimilitude in the Gothic may

have been an attempt to present his own work as the better

representation of the whole nature of man. Since Sade

professed that the ultimate goal of an author should be to

deliver an accurate portrayal of man, it is believed that

Sade's attempts to separate himself from the Gothic novel

highlights this conviction. For Sade, that his work was

best suited for the accomplishment of this goal was in

part because he was not chained down by the supernatural

silliness that dominated late 18th century fiction.

Moreover, it is believed that Sade praised The Monk

(which displays Ambrosio’s sacrifice of his humanity to

his unrelenting sexual appetite) as the best Gothic novel

chiefly because its themes were the closest to those

within his own work.

Sade's fiction has been tagged under many different titles, including pornography, Gothic, and baroque. Sade’s most famous books are often classified not as Gothic but as a libertine novel, and include the novels Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue; Juliette; The 120 Days of Sodom; and Philosophy in the Bedroom. These works challenge perceptions of sexuality, religion, law, age and gender in ways that Sade would argue are incompatible with the supernatural. The issues of sexual violence, sadomasochism and pedophilia stunned even those contemporaries of Sade who were quite familiar with the dark themes of the Gothic novel during its popularity in the late 18th century. Suffering is the primary rule, as in these novels one must often decide between sympathizing with the torturer or the victim. While these works focus on the dark side of human nature, the magic and phantasmagoria that dominates the Gothic is noticeably absent and is the primary reason these works are not considered to fit the genre.

Through the unreleased passions of his libertines, Sade

wished to shake the world at its core. With 120 Days,

for example, Sade wished to present "the most impure tale

that has ever been written since the world exists."

Though much of the fiction written by the Marquis de Sade has been classified as libertine, his tales in The Crimes of Love utilize Gothic conventions. Subtitled “Heroic and Tragic Tales”, Sade combines romance and horror, employing several Gothic tropes for dramatic purposes. There is blood, banditi, corpses, and, of course, insatiable lust. Compared to works like Justine, here Sade is relatively tame, as overt eroticism and torture is subtracted for a more psychological approach. It is the impact of sadism instead of acts of sadism itself that emerge in this work, unlike the aggressive and rapacious approach in his libertine works.

An example is “Eugenie de Franval”, a tale of incest and retribution. In its portrayal of conventional moralities it is somewhat of a departure from the erotic cruelties and moral ironies that dominate his libertine works. It opens with a domesticated approach:

“To enlighten mankind and improve its morals is the only lesson which we offer in this story. In reading it, may the world discover how great is the peril which follows the footsteps of those who will stop at nothing to satisfy their desires.”

Descriptions in Justine seem to anticipate Radcliffe’s scenery in Mysteries of Udolpho and the vaults in The Italian but unlike these stories, there is no escape for Sade’s virtuous heroine, Sophie. Unlike the milder Gothic fiction of Radcliffe, Sade’s horror ends in sodomy, rape or torture. To have a character like Sophie, who is stripped without ceremony and bound to a wheel for fondling and thrashing, would be unthinkable in the domestic Gothic fiction written for the bourgeoisie. Sade even contrives a kind of affection between Sophie and her tormentors, suggesting shades of masochism in his heroine.

Despite the strong adverse reaction to Sade’s work and Sade’s own disassociation from the Gothic novel, the similarities between the fiction of sadism and the Gothic novel were much closer than many of its readers or providers even realized. After the controversy surrounding Matthew Lewis' The Monk, Minerva Press released The New Monk as a supposed indictment of a wholly immoral book. It features the sadistic Mrs. Rod, whose boarding school for young women becomes a torture chamber equipped with its own "flogging - room." Ironically, The New Monk wound up increasing the level of cruelty, but as a parody of the genre, it illuminates the link between sadism and the Gothic novel.