<Back to Index>

- Poet Paul Éluard, 1895

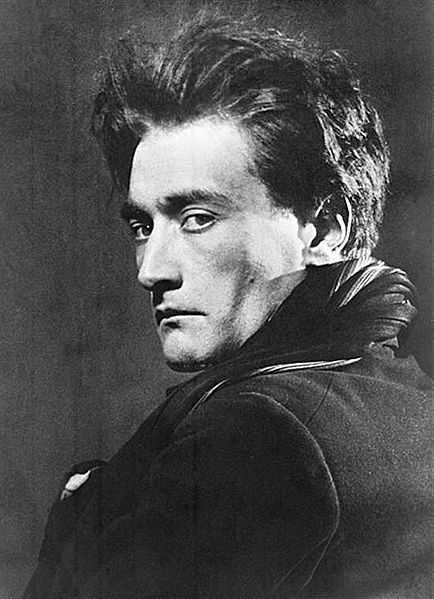

- Writer and Actor Antonin Artaud, 1896

PAGE SPONSOR

Paul Éluard, born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel (14 December 1895 – 18 November 1952), was a French poet who was one of the founders of the surrealist movement.

Éluard was born in Saint - Denis, Seine - Saint - Denis, France, the son of Clément Grindel and wife Jeanne Cousin. At age 16 he contracted tuberculosis and interrupted his studies. He met Gala, born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, whom he married in 1917, in the Swiss sanatorium of Davos. Together they had a daughter named Cécile. Around this time Éluard wrote his first poems. He was particularly inspired by Walt Whitman. In 1918, Jean Paulhan “discovered” him and introduced him to André Breton and Louis Aragon. After collaborating with German Dadaist Max Ernst, who had entered France illegally, in 1921, he entered into a menage a trois living arrangement with Gala and Ernst in 1922.

After a marital crisis, he traveled, returning to France in 1924. Éluard's writings of this period reflect his tumultuous experiences. In 1929 he had another bout of tuberculosis and separated from Gala when she left him for Salvador Dalí.

In 1934, he married Nusch (Maria Benz), a model and a friend of his friends Man Ray and Pablo Picasso, who was considered somewhat of a mascot of the surrealist movement. During World War II, he was involved in the French Resistance, during which time he wrote Liberty (1942), Les sept poèmes d'amour en guerre (1944) and En avril 1944: Paris respirait encore! (1945, illustrated by Jean Hugo).

He joined the French Communist Party in 1942, which led to his break from the Surrealists, and he later eulogized Joseph Stalin in his political writings. Milan Kundera

has recalled he was shocked when he heard of Éluard's public

approval of the hanging of Éluard's friend, the Prague writer Zavis Kalandra in 1950.

His grief at the premature death of his wife Nusch in 1946 inspired the work "Le temps déborde" in 1947. The principles of peace, self - government, and liberty became his new passion. He was a member of the Congress of Intellectuals for Peace in Wrocław in 1948, which he persuaded Pablo Picasso to participate in.

Éluard met his last wife, Dominique Laure, at the Congress of Peace in Mexico in 1949. They married in 1951. He dedicated his work The Phoenix to her.

Paul Éluard died from a heart attack in November 1952. His funeral was held in Charenton - le - Pont, and organized by the Communist Party.

He is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Antoine Marie Joseph Artaud, better known as Antonin Artaud (4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948), was a French playwright, poet, actor and theater director. Antonin is a diminutive form of Antoine "little Anthony", and was among a list of names which Artaud used throughout his writing career.

Antonin Artaud was born in Marseille, France, to Euphrasie Nalpas and Antoine - Roi Artaud. Both his parents were natives of Smyrna (modern day İzmir), and he was greatly affected by his Greek ancestry. His mother gave birth to nine children, but only Antonin and one sister survived infancy. When he was four years old, Artaud had a severe case of meningitis, which gave Artaud a nervous, irritable temperament throughout his adolescence. He also suffered from neuralgia, stammering and severe bouts of clinical depression, which was treated with the use of opium — resulting in a life long addiction.

Artaud's parents arranged a long series of sanatorium

stays for their temperamental son, which were both prolonged and

expensive. This lasted five years, with a break of two months in June

and July 1916, when Artaud was conscripted into the French Army. He was allegedly discharged due to his self induced habit of sleepwalking. During Artaud's "rest cures" at the sanatorium, he read Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe. In May 1919, the director of the sanatorium prescribed laudanum for Artaud, precipitating a lifelong addiction to that and other opiates.

In March 1920, Artaud moved to Paris to pursue a career as a writer, and instead discovered he had a talent for avant garde theater. Whilst training and performing with the most acclaimed directors of the day, most notably Charles Dullin and Georges Pitoeff, he continued to write both poetry and essays. At the age of 27, he mailed some of his poems to the journal La Nouvelle Revue Française; they were rejected, but the editor, Jacques Rivière, wrote back seeking to understand him, and a relationship in letters had developed. This epistolary work, Correspondance avec Jacques Rivière, was Artaud's first major publication.

Artaud cultivated a great interest in cinema as well, writing the scenario for the first Surrealist film, The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928), directed by Germaine Dulac. Dali and Buñuel, two key Spanish surrealists, took their cue for Un Chien Andalou (1929) from this film. He also acted in Abel Gance's Napoleon (1927) in the role of Jean - Paul Marat, and in Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) as the monk Massieu. Artaud's portrayal of Marat used exaggerated movements to convey the fire of Marat's personality.

In 1926 - 28, Artaud ran the Alfred Jarry Theater, along with Roger Vitrac. He produced and directed original works by Vitrac, as well as pieces by Claudel and Strindberg. The theater advertised that they would produce Artaud's play Jet de sang in their 1926 - 1927 season, but it was never mounted and was not premiered until 40 years later. The Theater was extremely short lived, but was attended by an enormous range of European artists, including André Gide, Arthur Adamov, and Paul Valéry.

In 1931, Artaud saw Balinese dance performed at the Paris Colonial Exposition. Although he did not fully understand the intentions and ideas behind traditional Balinese performance, it influenced many of his ideas for Theater. Also during this year, the 'First Manifesto for a Theater of Cruelty' was published in La Nouvelle Revue Française which would later appear as a chapter in The Theater and Its Double. In 1935, Artaud's production of his adaptation of Shelley's The Cenci premiered. The Cenci was a commercial failure, although it employed innovative sound effects — including the first theatrical use of the electronic instrument the Ondes Martenot -- and had a set designed by Balthus.

After the production failed, Artaud received a grant to travel to Mexico, where in 1936 he met his first (Mexican) Parisian friend, the painter Federico Cantú when he gave lectures on the decadence of Western civilization. He also studied and lived with the Tarahumaran people and experimented with peyote, recording his experiences, which were later released in a volume called Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara. The content of this work closely resembles the poems of his later days, concerned primarily with the supernatural. Artaud also recorded his horrific withdrawal from heroin upon entering the land of the Tarahumaras. Having deserted his last supply of the drug at a mountainside, he literally had to be hoisted onto his horse, and soon resembled, in his words, "a giant, inflamed gum". Artaud would return to opiates later in life.

In 1937, Artaud returned to France where he obtained a walking stick of knotted wood that he believed belonged not only to St. Patrick, but also Lucifer and Jesus Christ. Artaud traveled to Ireland, landing at Cobh and traveling to Galway, in an effort to return the staff, though he spoke very little English and was unable to make himself understood. He would not have been admitted at Cobh, according to Irish government documents, except that he carried a letter of introduction from the Paris embassy. The majority of his trip was spent in a hotel room that he was unable to pay for. He was forcibly removed from the grounds of Milltown House, a Jesuit community when he refused to leave. Before deportation he was briefly confined in the notorious Mountjoy Prison. According to Irish Government papers he was deported as "a destitute and undesirable alien". On his return trip by ship, Artaud believed he was being attacked by two crew members and retaliated. He was arrested and put in a straitjacket.

His best known work, The Theater and Its Double, was published in 1938. This book contained the two manifestos of the Theater of Cruelty.

The return from Ireland brought about the beginning of the final phase of Artaud's life, which was spent in different asylums. When France was occupied by the Nazis, friends of Artaud had him transferred to the psychiatric hospital in Rodez, well inside Vichy territory, where he was put under the charge of Dr. Gaston Ferdière. Ferdière began administering electroshock treatments to eliminate Artaud's symptoms, which included various delusions and odd physical tics. The doctor believed that Artaud's habits of crafting magic spells, creating astrology charts, and drawing disturbing images, were symptoms of mental illness. The electroshock treatments have created much controversy, although it was during these treatments — in conjunction with Ferdière's art therapy — that Artaud began writing and drawing again, after a long dormant period. In 1946, Ferdière released Artaud to his friends, who placed him in the psychiatric clinic at Ivry - sur - Seine. Current psychiatric literature describes Artaud as having schizophrenia, with a clear psychotic break late in life and schizotypal symptoms throughout life.

Artaud was encouraged to write by his friends, and interest in his work was rekindled. He visited an exhibition of works by Vincent van Gogh which resulted in a study Van Gogh le suicidé de la société [Van Gogh, The Man Suicided by Society], published by K éditeur, Paris, 1947 which won a critics' prize. He recorded Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu [To Have Done With the Judgment of god] between 22 and 29 November 1947. This work was shelved by Wladimir Porché, the director of the French Radio, the day before its scheduled airing on 2 February 1948. The performance was prohibited partially as a result of its scatological, anti - American, and anti - religious references and pronouncements, but also because of its general randomness, with a cacophony of xylophonic sounds mixed with various percussive elements. While remaining true to his Theater of Cruelty and reducing powerful emotions and expressions into audible sounds, Artaud had utilized various, somewhat alarming cries, screams, grunts, onomatopoeia and glossolalia.

As a result, Fernand Pouey, the director of dramatic and literary broadcasts for French radio, assembled a panel to consider the broadcast of Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu. Among the approximately 50 artists, writers, musicians and journalists present for a private listening on 5 February 1948 were Jean Cocteau, Paul Éluard, Raymond Queneau, Jean - Louis Barrault, René Clair, Jean Paulhan, Maurice Nadeau, Georges Auric, Claude Mauriac, and René Char. Although the panel felt almost unanimously in favor of Artaud's work, Porché refused to allow the broadcast. Pouey left his job and the show was not heard again until 23 February 1948 at a private performance at the Théâtre Washington.

In January 1948, Artaud was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. He died

shortly afterwards on 4 March 1948, alone in the psychiatric clinic. It

was suspected that he died from a lethal dose of the drug chloral hydrate,

although it is unknown whether he was aware of its lethality. Thirty

years later, French radio finally broadcast the performance of Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu.

Artaud believed that theater should affect the audience as much as possible, therefore he used a mixture of strange and disturbing forms of lighting, sound and other performance elements.

In his book The Theater and Its Double, which contained the first and second manifesto for a "Theater of Cruelty," Artaud expressed his admiration for Eastern forms of theater, particularly the Balinese. He admired Eastern theater because of the codified, highly ritualized and precise physicality of Balinese dance performance, and advocated what he called a "Theater of Cruelty". At one point, he stated that by cruelty he meant not exclusively sadism or causing pain, but just as often a violent, physical determination to shatter the false reality. He believed that text had been a tyrant over meaning, and advocated, instead, for a theater made up of a unique language, halfway between thought and gesture. Artaud described the spiritual in physical terms, and believed that all theater is physical expression in space.

- The Theater of Cruelty has been created in order to restore to the theater a passionate and convulsive conception of life, and it is in this sense of violent rigor and extreme condensation of scenic elements that the cruelty on which it is based must be understood. This cruelty, which will be bloody when necessary but not systematically so, can thus be identified with a kind of severe moral purity which is not afraid to pay life the price it must be paid.

- – Antonin Artaud, The Theatre of Cruelty, in The Theory of the Modern Stage (ed. Eric Bentley), Penguin, 1968, p.66

Evidently, Artaud's various uses of the term cruelty must be examined to fully understand his ideas. Lee Jamieson has identified four ways in which Artaud used the term cruelty. First, it is employed metaphorically to describe the essence of human existence. Artaud believed that theater should reflect his nihilistic view of the universe, creating an uncanny connection between his own thinking and Nietzsche's:

[Nietzsche's] definition of cruelty informs Artaud's own, declaring that all art embodies and intensifies the underlying brutalities of life to recreate the thrill of experience ... Although Artaud did not formally cite Nietzsche, [their writing] contains a familiar persuasive authority, a similar exuberant phraseology, and motifs in extremis ...

- – Lee Jamieson, Antonin Artaud: From Theory to Practice, Greenwich Exchange, 2007, p.21-22

Artaud's second use of the term (according to Jamieson), is as a form of discipline. Although Artaud wanted to "reject form and incite chaos" (Jamieson, p. 22), he also promoted strict discipline and rigor in his performance techniques. A third use of the term was ‘cruelty as theatrical presentation’. The Theater of Cruelty aimed to hurl the spectator into the center of the action, forcing them to engage with the performance on an instinctive level. For Artaud, this was a cruel, yet necessary act upon the spectator designed to shock them out of their complacency:

Artaud sought to remove aesthetic distance, bringing the audience into direct contact with the dangers of life. By turning theater into a place where the spectator is exposed rather than protected, Artaud was committing an act of cruelty upon them.

- – Lee Jamieson, Antonin Artaud: From Theory to Practice, Greenwich Exchange, 2007, p.23

Artaud wanted to put the audience in the middle of the 'spectacle' (his term for the play), so they would be 'engulfed and physically affected by it'. He referred to this layout as being like a 'vortex' - a constantly shifting shape - 'to be trapped and powerless'.

Finally, Artaud used the term to describe his philosophical views.

Imagination, to Artaud, was reality; he considered dreams, thoughts and delusions as no less real than the "outside" world. To him, reality appeared to be a consensus, the same consensus the audience accepts when they enter a theater to see a play and, for a time, pretend that what they are seeing is real.

Artaud saw suffering as essential to existence and thus rejected all utopias as inevitable dystopia. He denounced the degradation of civilization, yearned for cosmic purification, and called for an ecstatic loss of the self. Hence Jane Goodall considers Artaud to be a modern Gnostic while Ulli Seegers stresses the Hermetic elements in his works.

A very important study on the Artaud work comes from Jacques Derrida.

According to the philosopher, as theatrical writer and actor, Artaud is

the embodiment of both an aggressive and repairing gesture, which

strikes, sounds out, is harsh in a dramatic way and with critical

determination as well. Identifying life as art, he was critically

focused on the western cultural social drama, to point out and deny the

double - dealing on which the western theatrical tradition is based; he

worked with the whirlpool of feelings and lunatic expressions, being

subjugated to a counter - force which came from the act of gesture.

Definitely, the Artaud work gave life to all of what has never been

admitted in art, all the torment and the labor into the creator

consciousness, which is about the research of the meaning of making a

work of art.

Artaud was heavily influenced by seeing a Colonial Exposition of Balinese Theater in Marseille. He read eclectically, inspired by authors and artists such as Seneca, Shakespeare, Poe, Lautréamont, Alfred Jarry and André Masson.

Mötley Crüe named the Theatre of Pain album after reading his proposal for a Theater of Cruelty, much as Christian Death had with their album Only Theatre of Pain. The band Bauhaus included a song about the playwright, called "Antonin Artaud", on their album Burning from the Inside. Charles Bukowski also claimed him as a major influence on his work. Influential Argentine hard rock band Pescado Rabioso recorded an album titled Artaud. Their leader Luis Alberto Spinetta wrote the lyrics partly basing them on Artaud's writings. Composer John Zorn has four records, "Astronome", "Moonchild", "Six Litanies for Heliogabalus" and "The Crucible" dedicated to Artaud.

Theatrical practitioner Peter Brook took inspiration from Artaud's "Theater of Cruelty" in a series of workshops that led up to his well known production of Marat / Sade. The Living Theatre was also heavily influenced by him, as was much English language experimental theater and performance art; Karen Finley, Spalding Gray, Liz LeCompte, Richard Foreman, Charles Marowitz, Sam Shepard, Joseph Chaikin, and more all named Artaud as one of their influences.

Poet Allen Ginsberg claimed his introduction to Artaud, specifically "To Have Done with the Judgement of god", by Carl Solomon had a tremendous influence on his most famous poem "Howl".

The popular mid twentieth century poet and lyricist Jim Morrison was directly influenced by Artaud's Theater of Cruelty. He employed a conscious, but sometimes unconscious, method of arousing the so-called "Rock Music" audience to face "reality", cathartically. He failed in this effort a majority of the time, often over - estimating the potential of the audience to transcend the bounds of superficial fandom and fad - induced behavior. Morrison enrolled in and attended Jack Hirschman's famous course on Artaud at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1964, while a undergraduate student majoring in Cinematography and Theater.

The novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi includes a debate between artists and poets concerning the merits of Artaud's "multiple talents" in comparison to the singular talents of other French writers.

Artaud also had a profound influence on the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, who borrowed Artaud's phrase "the body without organs" to describe their conception of the virtual dimension of the body and, ultimately, the basic substratum of reality.