<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Hans Reichenbach, 1891

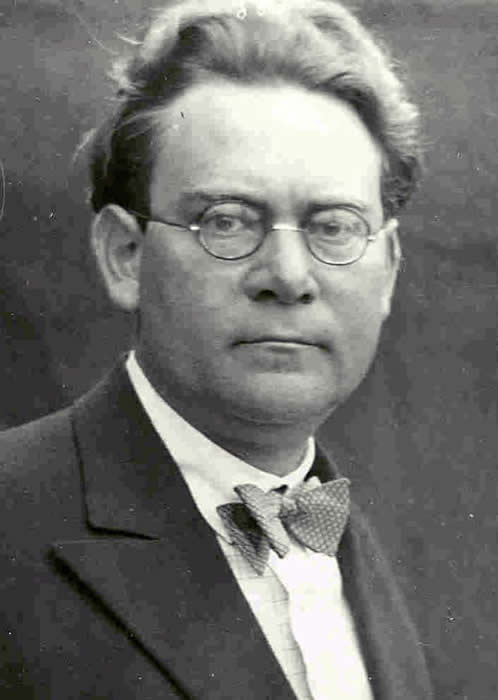

- Philosopher, Sociologist and Political Economist Otto Neurath, 1882

PAGE SPONSOR

Hans Reichenbach (September 26, 1891 in Hamburg – April 9, 1953 in Los Angeles) was a leading philosopher of science, educator and proponent of logical empiricism. Reichenbach is best known for founding the Berlin Circle, and as the author of The Rise of Scientific Philosophy.

After completing the secondary school in Hamburg with his older brother Bernhard Reichenbach who would go on to be a member of the Communist Workers' Party of Germany, Hans studied civil engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Stuttgart, and physics, mathematics and philosophy at various universities, including Berlin, Erlangen, Göttingen and Munich. Among his teachers were Ernst Cassirer, David Hilbert, Max Planck, Max Born and Arnold Sommerfeld. Reichenbach was active in youth movements and student organizations, and published articles about the university reform, the freedom of research, and against anti - Semitic infiltration in student organizations. Reichenbach himself was of Jewish ancestry.

Reichenbach received a degree in philosophy from the University of Erlangen in 1915 and his dissertation on the theory of probability, supervised by Paul Hensel and Emmy Noether, was published in 1916. Reichenbach served during World War I on the Russian front, in the German army radio troops. In 1917 he was removed from active duty, due to an illness, and returned in Berlin. While working as a physicist and engineer, Reichenbach attended Albert Einstein's lectures on the theory of relativity in Berlin from 1917 to 1920.

In 1920 Reichenbach began teaching at the Technische Hochschule at Stuttgart as Privatdozent. In the same year, he published his first book on the philosophical implications of the theory of relativity, The Theory of Relativity and A Priori Knowledge, which criticized the Kantian notion of synthetic a priori. He subsequently published Axiomatization of the Theory of Relativity (1924), From Copernicus to Einstein (1927) and The Philosophy of Space and Time (1928), the last stating the logical positivist view on the theory of relativity.

In 1926, with the help of Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Max von Laue, Reichenbach became assistant professor in the physics department of Berlin University. He gained notice for his methods of teaching, as he was easily approached and his courses were open to discussion and debate. This was highly unusual at the time, although the practice is nowadays a common one.

In 1928, Reichenbach founded the so-called "Berlin Circle" (German: Die Gesellschaft für empirische Philosophie; English: Society for Empirical Philosophy). Among its members were Carl Gustav Hempel, Richard von Mises, David Hilbert and Kurt Grelling. In 1930 he and Rudolf Carnap began editing the journal Erkenntnis ("Knowledge").

When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, Reichenbach was immediately dismissed from his appointment at the University of Berlin under the government's so called "Race Laws" due to his Jewish ancestry. He thereupon emigrated to Turkey, where he headed the Department of Philosophy at the University of Istanbul. He introduced interdisciplinary seminars and courses on scientific subjects, and in 1935 he published The Theory of Probability.

In 1938, with the help of Charles W. Morris, Reichenbach moved to the United States to take up a professorship at the University of California, Los Angeles, in its Philosophy Department. His work on the philosophical foundations of quantum mechanics was published in 1944, followed by Elements of Symbolic Logic in 1947, and The Rise of Scientific Philosophy — his most popular book — in 1951.

Reichenbach helped establish UCLA as a leading philosophy department in the United States in the post war period. Carl Hempel, Hilary Putnam and Wesley Salmon are perhaps his most prominent students.

Reichenbach died in Los Angeles on April 9, 1953, while working on problems in the philosophy of time and on the nature of scientific laws. As part of this he proposed a three part model of time in language, involving speech time, event time and - critically - reference time, which has been used by linguists since for describing tenses. This work resulted in two books published posthumously: The Direction of Time and Nomological Statements and Admissible Operations.

Otto Neurath (Vienna, December 10, 1882 - Oxford, December 22, 1945) was an Austrian philosopher of science, sociologist and political economist. Before he was to flee his native country in 1934, Neurath was one of the leading figures of the Vienna Circle.

Neurath was born in Vienna, the son of Wilhelm Neurath (1840 – 1901), a well known political economist at the time. He studied mathematics in Vienna and gained his Ph.D. in the department of Political Science and Statistics at the University of Berlin.

He married Anna Schapire in 1907. She died as a result of childbirth (Paul Neurath) in 1911, and he married a close friend, the mathematician and philosopher Olga Hahn. Perhaps because of Olga's blindness and then because of the outbreak of war, his son, Paul Neurath was sent to a children's home outside Vienna, where Neurath's mother lived, and returned to live with his father and Olga when he was nine years old.

Neurath taught political economy at the Neue Wiener Handelsakademie (New College of Commerce, Vienna) until war broke out. Subsequently he became director of the Deutsches Kriegwirtschaftsmuseum (German Museum of War Economy, later the Deutsches Wirtschaftmuseum) at Leipzig. Wolfgang Schumann, known from the Dürerbund for which Neurath had written many articles, urged him to work out a plan for socialization. Neurath joined the German Social Democratic Party in 1918 - 19 and ran an office for central economic planning in Munich. When the Bavarian Soviet Republic was defeated, Neurath was imprisoned but returned to Austria after intervention from the Austrian government. While in prison he wrote "Anti - Spengler", a critical attack on Oswald Spengler's "Decline of the West".

In Red Vienna, he joined the Social Democrats and became secretary of the Austrian Association for Housing and Small Gardens (Verband für Siedlungs - und Kleingartenwesen), a collection of self - help groups that set out to provide housing and garden plots to its members. In 1923, he founded a new museum for housing and city planning called Siedlungsmuseum. In 1925 he renamed it Gesellschafts - und Wirtschaftsmuseum in Wien (Museum of Society and Economy in Vienna) and founded an own association for it, in which the Vienna city administration, the trade unions, the Chamber of Workers and the Bank of Workers became members, then mayor Karl Seitz having acted as first proponent of the association. Julius Tandler, city councilor for welfare and health, served at the first board of the museum together with other prominent social democratic politicians. The museum was provided with exhibition rooms at buildings of the city administration, the most prominent being the People's Hall at the Vienna City Hall. To make the museum understandable for everybody, Neurath worked on graphic design and visual education. With the illustrator Gerd Arntz and with Marie Reidemeister (who he would marry in 1941), Neurath created Isotype, a symbolic way of representing quantitative information via easily interpretable icons. At international conventions of city planners, Neurath presented and promoted his communication tools.

During the 1920s, Neurath also became an ardent logical positivist, and was the main author of the Vienna Circle manifesto. He was the driving force behind the Unity of Science movement and the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. During the 1930s, he also began promoting Isotype as an International Picture Language, connecting it both with the adult education movement and with the Internationalist passion for new and artificial languages, although he stressed in talks and correspondence that Isotype was not intended to be a stand alone language, and was limited in what it could communicate.

During the Austrian Civil War of 1934, Neurath had been working in Moscow. Anticipating problems, he had asked to get a coded message in case it would be dangerous for him to return to Austria. As Marie Reidemeister reported later, after receiving the telegram "Carnap is waiting for you" Neurath chose to travel to The Hague instead of Vienna, where he could continue his international work. His Vienna team soon dispersed, the museum's work came to a hold.

His wife fled to Holland as well. There Olga died and after the Luftwaffe bombing of Rotterdam he fled with Marie Reidemeister to England, crossing the Channel with other refugees in an open boat. He and Marie married in 1941, after a period interned on the Isle of Man (Neurath was in Onchan camp). In England, he and Marie set up the Isotype Institute in Oxford and he was asked to advise on, and design Isotype charts for, the intended redevelopment of the slums of Bilston, near Wolverhampton.

Neurath died, suddenly and unexpectedly in December 1945. After his death, Marie Neurath continued the work of the Isotype Institute, publishing Neurath's writings posthumously, completing projects he had started and writing many children's books using the Isotype system, until her death in the 1980s.

Most work by and about Neurath is still available only in German. However he also wrote in English, using Ogden's Basic English. His scientific papers are held at the Noord - Hollands Archief in Haarlem; the Otto and Marie Neurath Isotype Collection is held in the Department of Typography & Graphic Communication at the University of Reading in England.

In one of his later and most important works, Physicalism, Neurath completely transformed the nature of the logical positivist discussion of the program of unifying the sciences. Neurath delineates and explains his points of agreement with the general principles of the positivist program and its conceptual bases:

- the construction of a universal system which would comprehend all of the knowledge furnished by the various sciences, and

- the absolute rejection of metaphysics, in the sense of all propositions not translatable into verifiable scientific sentences.

He then rejects the positivist treatment of language in general and, in particular, some of Wittgenstein's early fundamental ideas.

First Neurath rejects isomorphism between language and reality as useless metaphysical speculation, which would call for explaining how words and sentences could represent things in the external world. Instead, Neurath proposed that language and reality coincide — that reality consists in simply the totality of previously verified sentences in the language, and "truth" of a sentence is about its relationship to the totality of already verified sentences. Either a sentence failing to "concord" (or cohere) with the totality of the sentences already verified, should be considered false, or that some of that totality's propositions must in some way be modified. He thus views truth as a question of internal coherence of linguistic assertions, rather than anything to do with facts or other entities in the world. Moreover, the criterion of verification is to be applied to the system as a whole (semantic holism) and not to single sentences. Such ideas exercised a profound influence over the holistic verificationism of W.V.O. Quine.

In fact, it was Quine, in Word and Object, who made famous Neurath's analogy which compares the holistic nature of language and consequently scientific verification with the construction of a boat which is already at sea:

We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom. Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support. In this way, by using the old beams and driftwood the ship can be shaped entirely anew, but only by gradual reconstruction.

Stanovich discusses this metaphor in context of memes and memeplexes and refers to this metaphor as a "Neurathian bootstrap".

Neurath also went on to reject the notion that science should be reconstructed in terms of sense data, since perceptual experiences are too subjective to constitute a valid foundation for the formal reconstruction of science. The phenomenological language that most positivists were still emphasizing was to be replaced, in his view, with the language of mathematical physics. This would allow for the objective formulations required because it is based on spatio - temporal coordinates. Such a physicalistic approach to the sciences would facilitate the elimination of every residual element of metaphysics because it would permit them to be reduced to a system of assertions relative to physical facts.

Finally, Neurath suggested that since language itself is a physical system, because it is made up of an ordered succession of sounds or symbols, it is capable of describing its own structure without contradiction.

These ideas helped form the foundation of the sort of physicalism which is still today the dominant position with regard to metaphysics and, especially, the philosophy of mind.