<Back to Index>

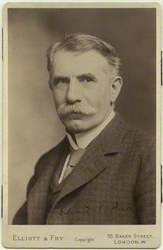

- Architect Edward Schroeder Prior, 1857

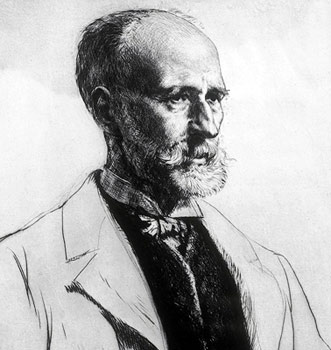

- Gardener and Journalist William Robinson, 1838

- Architect Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott, 1865

PAGE SPONSOR

Edward Schroeder Prior (1857 – 1932) was an architect who was instrumental in establishing the arts and crafts movement. He was one of the foremost theorists of the second generation of the movement, writing extensively on architecture, art, craftsmanship and the building process and subsequently influencing the training of many architects.

He was a major contributor to the development of the Art Workers Guild and other organizations that lay at the heart of the movement’s attempts to bring art, craftsmanship and architecture closer together. His scholarly work, particularly A History of Gothic Art in England (1900), achieved international acclaim. He became one of the leading architectural educationalists of his generation. As Slade Professor of Art at Cambridge he established the Cambridge School of Architectural Studies.

Initially his buildings show the influence of his mentor Norman Shaw and Philip Webb, but Prior experimented with materials, massing and volume from the start of his independent practice. He developed a style that was intensely individual and a practical philosophy of construction that was perhaps nearer to Ruskin's ideal of the "builder designer" than that of any other arts and crafts architect.

The buildings of his maturity, such as The Barn, Exmouth, and Home Place, Kelling, are among the most original of the period. In St Andrew's Church, Roker, he produced his masterpiece, a church that is now recognized as one of the best of the early 20th century.

Prior experimented with unusual plans, massing and volumes and became more and more interested in the nature and use of material and texture. In particular he experimented with reinforced concrete, which was used extensively in Home Place and St Andrew's.

Prior's approach to building was to ensure the use of the best quality materials, developing constructional techniques in partnership with the craftsmen builders. Despite the pioneering use of concrete and experimentation with structural systems, Prior's buildings seem to have relatively few construction and material defects, a tribute to his philosophy and skills.

Edward Schroeder Prior was born in Greenwich on July 4, 1852, his parents' fourth son, one of eleven children. His father John Venn Prior, who was a barrister in the Chancery division, died at the age of 43 as a result of a fall from a horse. Edward was aged 10 at the time. His mother moved the family to Harrow, where Edward's eldest brother John Templer was at school and where widows did not have to pay school fees if they were day boys. Here, next door to the house of Matthew Arnold, she started a school for children whose parents were in India, and Edward was one of its first pupils.

His grandfather Dr John Prior was a prominent figure in the Evangelical movement and a member of the Clapham Sect that revolved around the Revd. John Venn, the first chairman of the Church Missionary Society, and included notable figures in the abolition of the slave trade, such as William Wilberforce and Zachary Maclaulay. Prior was later to work for Evangelical patrons such as the Cambridge Missionary Society as well as High Church Romanists.

In 1863 at the unusually young age of 11, Edward entered Harrow School. Here his interest in natural history, art, architecture and science was fostered, particularly by F.W. Farrar, H.M. Butler and B.F. Wescott, his housemaster and private tutor. (Prior remained a committed naturalist throughout his life. His collections of Lepidoptera remain largely intact, held by the Museum of St Albans.) Prior remained connected to Harrow School and was later to design several buildings for the school.

In 1869 Prior won the Sayer Scholarship "for the promotion of classical learning and taste" to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, to read the Classical Tripos. He augmented the Sayer Scholarship by also gaining a College Scholarship. In the same year B.F. Westcott was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity. Prior continued to gain from his instruction in architectural drawing at Cambridge. Other influences were Matthew Digby Wyatt and Sidney Colvin, the first and second Slade Professors of Fine Art. Wyatt's lecture program for 1871 included engraving, woodcutting, stained glass and mosaic. Prior's interest in the applied arts was probably strongly encouraged by Wyatt. Colvin, a friend of Edward Burne - Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was elected Slade Professor in January 1873.

At Cambridge. Prior was also exposed to the work of William Morris. For example G.F. Bodley employed Morris & Co. to decorate All Saints Church in 1864 - 1866 and to design the glass for others of his Cambridge buildings.

Prior was a noted athlete at Cambridge. He was a blue in long jump and high jump and won the British Amateur High Jump in 1872.

In the autumn of 1874 Prior was articled to Norman Shaw at 30 Argyll Street. Shaw seems to have been his first choice as mentor. Shaw had been George Edmund Street's chief clerk and had set up in partnership with William Eden Nesfield in 1866. The partnership only lasted until 1869, though Nesfield continued to share the premises until 1876. Shaw had made his name through country houses such as Cragside, Northumberland. At the time Shaw’s architecture was regarded as original and entirely on its own by the younger generation of architects. His practice was already attracting brilliant young architects. Shaw's pupils were articled for three years, learning to measure buildings and to draw plans and elevations for contracts.

At the time Prior joined Shaw the practice was still small, with only three rooms shared with Nesfield. Shaw had a limited number of assistants and pupils, including Ernest Newton (1856 – 1922), who had joined Shaw in 1873 but who left to set up on his own in 1879, Richard Creed (1846 – 1914) and William West Neve (1852 – 1942), who was also soon to set up in practice on his own behalf. Nesfield's assistant at the time was E.J. May, a former pupil of Decimus Burton, who had been responsible for the Palm House at Kew Gardens among other buildings.

It was only later that the group that produced some of the most exiting Arts and Crafts Movement Architecture and scholarship and provided the impetus to the Movement came together under Shaw. William Lethaby (1857 – 1931) joined the practice as Chief Assistant in 1878, Mervyn Macartney (1853 – 1932) joined as a pupil in the same year and Gerald Horsley (1862 – 1917) in 1879. May and Newton both set up in practice nearby. Horsley later illustrated Prior's A History of Gothic Art in England (1900). The St George's Art Society grew out of the discussions held among Shaw's past and present staff at Newton's Hart Street offices.

In the late 1870s and early 1880s Shaw's prestige was greatly enhanced by major success with "spectacular perspectives" exhibited at Royal Academy exhibitions. As Chief Draftsman Newton was probably the main influence on the drawing style though Prior may have made a considerable contribution.

By 1877 Shaw's health was deteriorating. His assistants were encouraged to supervise jobs and live on site. Prior was appointed Clerk of Works for St Margaret's Church, Ilkley, administering the works from November 1877 to August 1879. Prior was responsible for the contract drawings and possibly for the design of the roof reinforcement and some of the detailing and furniture, such as the font. Prior had been eager to gain practical experience of construction, an area of the profession in which Shaw was loath to give instruction. The expertise of the craftsmen at Ilkley made a deep impression on Prior;

| “ | He (Prior) went (to Ilkley) and then found that the idea of wonderful construction was all an imposture: there was no science of construction, but there was an experience of construction to be gained by the man who worked with his hands and not the man who made the drawing. | ” |

Prior only stayed a few months further with Shaw on his return from Ilkley. In 1880 he began his own practice at 17 Southampton Road, in close proximity to Shaw and others of his former employees. Reginald Blomfield leased an office on the second floor. Prior occupied the building until 1885 and again in 1889 - 94 and 1901.

His early commissions were primarily located in areas where he had connections, in Harrow and around Bridport in Dorset, where his father had lived and his mother's relatives, the Templers, were prominent and in Cambridge where he had been at University. The opening of the Metropolitan Railway to Harrow in 1880 and his connections with Harrow in particular encouraged Prior to work in the Harrow area.

His work in Dorset was to lead to his marriage. Whilst designing Pier Terrace at West Bay, Prior met Louisa Maunsell, the daughter of the vicar of nearby Symondsbury. They were married in Symmondsbury Church on 11 August 1885. Mervyn Macatney was best man.

The Priors lived in 6 Bloomsbury Square from 1885 - 1889. Here his daughters Laura and Christobel were born. Prior leased Bridgefoot, Iver, Bucks as a country residence in 1889, but on the birth of his second daughter it was leased to the architect G.F. Bodley.

In 1894 Prior moved to 10 Melina Place, St John's Wood, next door to Voysey, resulting in the development of a long term friendship and exchange of ideas between the two men, to the extent that Voysey is recorded as having painted the roofs of Prior’s seminal Model for a Dorsetshire Cottage

Prior moved to Sussex in 1907 initially living in an early 18th century house at 7 East Pallant, Chichester. In 1908 he bought an 18th century house in Mount Lane with an adjacent warehouse which he converted to provide a studio. He continued the London practice as 1 Hare Court, Temple until the middle of the First World War. On his appointment as Slade Professor at Cambridge Prior also bought a house, Fariview in Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge.

After the First World War Prior unsuccessfully tried to restart his practice with H.C. Hughes. He started a commission for a house outside Cambridge but fell into a dispute with the client over the materials for the boundary hedge. Hughes took over the job as his own. Prior's scheme for the ciborium at Norwich Cathedral was dropped deeply disappointing him.

In the post war years he only undertook the design of war memorials at Maiden Newton in Dorset and for Cambridge Union Rugby Club.

Prior played a crucial role in the establishment of the Guilds that were the intellectual focus of the Arts and Crafts Movement. The St George's Art Society 1883 - 1886 was founded by a group of architects who had seen service in the Shaw's offices, Ernest Newton, Mervyn Macartney, Reginald Barratt, Edwin Hardy, William Lethaby and Prior, to discuss Art and Architecture. It initially met in Newton's chambers by St George's Church, Bloomsbury. Prior was on the committee. Monthly meetings were held and papers read, Prior speaking on "Terracotta" and "Tombs". Trips were arranged to see buildings.

At the October 1883 meeting it was decided that it would be preferable to found a new organization that would bring together "craftsmen in Architecture, Painting, Sculpture and the kindred Arts." The proposals stemmed from the members' alarm at the lack of relationship between architects and artists and their dissatisfaction with the Institute of British Architects and the Royal Academy.

After various consultations invitations were sent out to twenty four artists including members of The fifteen, founded by the designer and writer Lewis Day and the illustrator and designer Walter Crane and other such as J.D. Sedding, Ernest George and Basil Champneys. Various names for the group were proposed and Prior's suggestion of the "Art Workers Guild" was accepted at the meeting of 11 March 1884. Prior also wrote the Guild's first prospectus.

The Guild was highly influential on the architecture of the Arts and Crafts Movement, but Prior remained only a minor player for some time, until he was elected to the governing committee in 1889. However the contact with other luminaries of the Society certainly encouraged Prior to rationalize and develop his theories. He was also able to call on the skills of a wide range of craft practitioners from the Guild for the design and construction of furniture for many of his buildings. Prior became Master in 1906.

Prior was also active in various other organizations of the time, including the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society of 1886, set up to combat the exclusiveness of the Royal Academy, and the National Association for the Advancement of Art and its Application to Industry of 1888, at which he gave his inspired lecture on "Texture as a Quality of Art and a Condition for Architecture" that set out the rationale behind his most significant buildings. His involvement with The Clergy and Artists’ Association of 1896, set up to improve the links between patron and producer, led directly to commissions for example for the lych gate at Methley Church.

During the late 1890s Prior's practice received few commissions. The study of Gothic art and architecture became one of Prior’s major concerns the period. In 1900 he published A History of Gothic Art in England, which as rapidly recognized as a standard text. This was followed by The Cathedral Builders in England in 1905, An Account of English Medieval Figure - Sculpture in 1912, which provided an exhaustive account of figurative sculpture from the 7th to the 16th Century for the first time.

A History of Gothic Art in England made Prior's scholastic reputation and contributed to his appointment as Slade Professor of Art at Cambridge University in 1905.

Prior first became involved in architectural education during the debate over the professionalization of architectural practice in the 1890s. The protest against examination and registration was launched by the Art Workers Guild, whose members believed, quite correctly, that RIBA wished to establish itself as the sole arbiter of the profession culminating in the publication of a collection of essays Architecture: A Profession or an Art in 1892, to which Prior contributed a chapter criticizing the common use of "hirelings" to do the architect's work. In the same year Prior, among others resigned from the RIBA.

As a result of the controversy members of the Guild became very interested in architectural education. The Architectural Association established a School of Handicraft and Design to extend its training scheme. It had been criticized for being too geared to the RIBA’s examination system. Prior was one of the architect - visitors who drew up projects and gave the "crits".

He became increasingly interested in education, giving lectures at various conferences, to the RIBA and schools of design. Moves were instigated to establish a School of Architecture at Cambridge in 1907. The syndicate seeking the establishment of the school included Prior's old headmaster Dr H.M. Butler, who was by then Dean of Trinity College, Dr Charles Waldstein, Slade Professor of Fine Art and William Ridgway the Disney Professor of Archaeology. The establishment of examinations were approved in 1908. Waldstein favored Prior as his successor. Prior was elected Slade Professor on 20 February 1912 with the role of developing the new School of Architecture. In 1915 the tenure of the Professorship was extended to life.

Prior established the syllabus for the School, oversaw the establishment of the Department and instigated a research program. The latter included experimental studies into the performance of limes and cements.

In many ways Prior fits the stereotype of a privileged late 19th Century ex public school boy, barrister's son and Cambridge Blue. His bullying, playful manner are well recorded:

| “ | On Saturdays Mr Shaw did not come to his office he worked at home. So just before the hour when the clerks were due to leave Mr Prior got hold of some brown paper and string and also of Federick O’Neil (Shaw’s latest pupil) and tied him up in a brown paper parcel and put him on Ma Heaton’s Hall Table. It was found later in the day who happened to pass through the hall.. | ” |

| “ | One day Mr Prior when on his way to the Office was caught in heavy driving rain without an overcoat. So his trousers were drenched through and through. He took them off..... When Mr Shaw happened to come into the office later on, he was startled to see a pair of legs dangling from Mr Prior’s stool. | ” |

However underlying the argumentative and bulling façade lurked an artist and scholar. He was and remained a Tory throughout his life, perhaps explaining his lack of interest in social housing and the garden city movement. Yet he was close friends with the socialist Lethaby and a strong opponent of the professionalization of architecture and believed that the architect should merely facilitate the work of craftsmen. In his long academic career he aimed to produce a "world of builders, who would build with the direct knowledge of working conditions".

His obituary in the Architect and Building News perhaps best summed him up:

And he could be something of a grizzly old bear at times, for he was pertinacious and his opinion once formed was hardly to be changed. To hear an argument — and we have heard several – between Prior and Leonard Stokes was an education. Yet it was a kindly bear withal, that would emerge, honors divided, from a wordy warfare with a joyous twinkle in its eye; and for any small personal attention or service, it could be immensely grateful and appreciative.

He remained as Slade Professor until his death from cancer in August the 19th 1932. He was buried in an unmarked grave at St. Mary’s Church, Apuldram. Few of his friends remained, Lethaby, Newton, and Horsley were all dead, and none of his former architectural colleagues attended his funeral.

William Robinson (5 July 1838 – 17 May 1935) was an Irish practical gardener and journalist whose ideas about wild gardening spurred the movement that evolved into the English cottage garden, a parallel to the search for honest simplicity and vernacular style of the British Arts and Crafts movement. Robinson is credited as an early practitioner of the mixed herbaceous border of hardy perennial plants, a champion too of the "wild garden", who vanquished the high Victorian pattern garden of planted - out bedding schemes. Robinson's new approach to gardening gained popularity through his magazines and several books — particularly The Wild Garden, illustrated by Alfred Parsons, and The English Flower Garden.

Robinson advocated more natural and less formal - looking plantings of hardy perennials, shrubs and climbers, and reacted against the High Victorian patterned gardening, which used tropical materials grown in greenhouses. He railed against standard roses, statuary, sham Italian gardens, and other artifices common in gardening at the time. Modern gardening practices first introduced by Robinson include: using alpine plants in rock gardens; dense plantings of perennials and ground covers that expose no bare soil; use of hardy perennials and native plants; and large plantings of perennials in natural looking drifts.

Robinson began his garden work at an early age, as a garden boy for the Marquess of Waterford at Curggaghmore. From there, he went to the estate of an Irish baronet in Ballykilcannan, Sir Hunt Johnson - Walsh, and was put in charge of a large number of greenhouses at the age of 21. According to one account, as the result of a bitter quarrel, one cold winter night in 1861 he let the fires go out, killing many valuable plants. Other accounts consider the story to be a gross exaggeration. Whether in haste after the greenhouse incident or not, Robinson left for Dublin in 1861, where the influence of David Moore, head of the botanical garden at Glasnevin, a family friend, helped him find work at the Botanical Gardens of Regent's Park, London, where he was given responsibility for the hardy herbaceous plants, specializing in British wildflowers.

At that time, the Royal Horticultural Society's Kensington gardens were being designed and planted with vast numbers of greenhouse flowers in mass plantings. Robinson wrote that "it was not easy to get away from all this false and hideous "art"." But his work with native British plants did allow him to get away to the countryside, where he "began to get an idea (which should be taught to every boy at school) that there was (for gardens even) much beauty in our native flowers and trees."

In 1866, at the age of 29, he became a fellow of the Linnean Society under the sponsorship of Charles Darwin, James Veitch, David Moore, and seven other distinguished botanists and horticulturists. Two months later, he left Regents Park to write for The Gardener's Chronicle and The Times, and represented the leading horticultural firm of Veitch at the 1867 Paris Exhibition. He began writing many of his publications, beginning with Gleanings from French Gardens in 1868, The Parks, Gardens, and Promenades of Paris in 1869, and Alpine Flowers for Gardens and The Wild Garden in 1870. In 1871 he launched his own gardening journal, simply named The Garden, which over the years included contributions from notables such as John Ruskin, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Gertrude Jekyll, William Morris, Dean Hole, Canon Ellacombe and James Britten.

His most influential books were The Wild Garden, which made his reputation and allowed him to start his magazine The Garden; and The English Flower Garden, 1883, which he revised in edition after edition and included contributions from his lifelong friend Gertrude Jekyll, among others. She later edited The Garden for a couple of years and contributed many articles to his publications, which also included Gardening Illustrated (from 1879).

He first met Jekyll in 1875 — they were in accord in their design principles and maintained a close friendship and professional association for over 50 years. He helped her on her garden at Munstead Wood; she provided plants for his garden at Gravetye Manor. Jekyll wrote about Robinson that:

...when English gardening was mostly represented by the innate futilities of the "bedding" system, with its wearisome repetitions and garish coloring, Mr William Robinson chose as his work in live to make better known the treasures that were lying neglected, and at the same time to overthrow the feeble follies of the "bedding" system. It is mainly owing to his unremitting labors that a clear knowledge of the world of hardy - plant beauty is now placed within easy reach of all who care to acquire it, and that the "bedding mania" is virtually dead.

Robinson also published God's Acre Beautiful or The Cemeteries of The Future, in which he applied his gardening aesthetic to urban churchyards and cemeteries. His campaign included trying to win an unwilling public to the advantages of cremation over burial, and he quite freely shared unsavory stories of what happened in certain crowded graveyards. He was instrumental in the founding of Golders Green Crematorium and designed the gardens there, which replaced the traditional Victorian mourning graveyard with open lawn, flowerbeds and woodland gardens.

With his writing career a financial success, in 1884 Robinson was able to purchase the Elizabethan Manor of Gravetye near East Grinstead in Sussex, along with about 200 acres (0.81 km2) of rich pasture and woodland. His diary of planting and care was published as Gravetye Manor, or Twenty Years of the Work round an old Manor House (1911). Gravetye would find practical fulfillment of many of Robinson's ideas of a more natural style of gardening. Eventually it would grow to nearly 1,000 acres (4 km2).

Much of the estate had been managed as a coppiced woodland, giving Robinson the opportunity to plant drifts of scilla, cyclamen and narcissus between the coppiced hazels and chestnuts. On the edges, and in the cleared spaces in the woods, Robinson established plantings of Japanese anemone, lily, acanthus and pampas grass, along with shrubs such as fothergilla, stewartia and nyssa. Closer to the house he had some flower beds; throughout he planted red valerian, which he allowed to spread naturally around paving and staircases. Robinson planted thousands of daffodils annually, including 100,000 narcissi planted along one of the lakes in 1897. Over the years he added hundreds of trees, some of them from American friends John Singer Sargent and Frederick Law Olmsted. Other features included an oval - shaped walled kitchen garden, a heather garden and a water garden with one of the largest collections of water lilies in Europe.

Robinson invited several well known painters to portray his own landscape artistry, including the English watercolorist Beatrice Parsons, the landscape and botanical painter Henry Moon, and Alfred Parsons. Moon and Parsons illustrated many of Robinson's works.

After Robinson's death, Gravetye Manor was left to the Forestry Commission, who left it derelict for many years. In 1958 it was leased to a restaurateur who refurbished the gardens, replacing some of the flower beds with lawn. Today, Gravetye Manor serves as a hotel and restaurant.

Through his magazines and books, Robinson challenged many gardening traditions and introduced new ideas that have become commonplace today. He is most linked with introducing the herbaceous border, which he referred to by the older name of 'mixed border' — it included a mixture of shrubs, hardy and half - hardy herbaceous plants. He also advocated dense plantings that left no bare soil, with the spaces between taller plants filled with what are now commonly called ground cover plants. Even his rose garden at Gravetye was filled with saxifrage between and under the roses. Following a visit to the Alps, Robinson wrote Alpine Flowers for Gardens, which for the first time showed how to use alpine plants in a designed rock garden.

His most significant influence was the introduction of the idea of wild gardening, which first appeared in The Wild Garden and was further developed in The English Flower Garden. The idea of introducing large drifts of native hardy perennial plants into meadow, woodland, and waterside is taken for granted today, but was revolutionary in Robinson's time. In the first edition, he happily used any plant that could be naturalized, including half - hardy perennials and natives from other parts of the world — thus Robinson's wild garden was not limited to locally native species. Robinson's own garden at Gravetye was planted on a large scale, but his wild garden idea could be realized in small yards, where the 'garden' is designed to appear to merge into the surrounding woodland or meadow. Robinson's ideas continue to influence gardeners and landscape architects today — from home and cottage gardens to large estate and public gardens.

In The Wild Garden Robinson set forth fresh gardening principles that expanded the idea of garden and introduced themes and techniques that are taken for granted today, notably that of "naturalized" plantings. Robinson's audience were not the owners of intensely gardened suburban plots, nor dwellers in gentrified country cottages seeking a nostalgic atmosphere; nor was Robinson concerned with the immediate surroundings of the English country house. Robinson's wild garden brought the untidy edges, where garden blended into the larger landscape into the garden picture: meadow, water's edge, woodland edges and openings.

The hardy plants Robinson endorsed were not all natives by any means: two chapters are devoted to the hardy plants from other temperate climate zones that were appropriate to naturalizing schemes. The narcissus he preferred were the small, delicate ones from the Iberian peninsula. Meadow flowers included goldenrod and asters, rampant spreaders from North America long familiar in English gardens. Nor did Robinson's 'wild' approach refer to letting gardens return back to their natural state — he taught a specific gardening method and aesthetic. The nature of plants' habit of growth and their cultural preferences dictated the free design, in which human intervention was to be kept undetectable.

Without being in any sense retrograde, Robinson's book brought attention back to the plants, which had been eclipsed since the decline of "gardenesque" plantings of the 1820s and 30s, during the use of tender annuals as massed color in patterned schemes of the mid century. The book's popularity was largely due to Robinson's promise that wild gardening could be easy and beautiful; that the use of hardy perennials would be less expensive and offer more variety than the frequent mass planting of greenhouse annuals; and that it followed nature, which he considered the source of all true design.

The book was dedicated to Robinson's friend S. Reynolds Hole, dean of Rochester, the "Dean Hole" of garden history, a connoisseur of hardy roses.

In The English Flower Garden, Robinson laid down the principles that revolutionized the art of gardening. Robinson's source of inspiration was the simple cottage garden, long neglected by the fashionable landscapists. In The English Flower Garden he rejected the artificial and the formal, specifically statuary, topiary, carpet bedding and waterworks — comparing the modern garden to "the lifeless formality of wall paper or carpet." The straight lines and form in many gardens were seen by Robinson to "carry the dead lines of the builder into the garden." He admired nature's diversity, and promoted creepers and ramblers, smaller plantings of roses, herbaceous plants and bulbs, woodland plants and winter flowers.

Robinson compared gardening to art, and wrote in the first chapter:

The gardener must follow the true artist, however modestly, in his respect for things as they are, in delight in natural form and beauty of flower and tree, if we are to be free from barren geometry, and if our gardens are ever to be true pictures.... And as the artist's work is to see for us and preserve in pictures some of the beauty of landscape, tree, or flower, so the gardener's should be to keep for us as far as may be, in the fullness of their natural beauty, the living things themselves.

The first part of The English Flower Garden covered garden design, emphasizing an approach that was individual and not stereotypical: "the best kind of garden grows out of the situation, as the primrose grows out of a cool bank." The second part covered individual plants, hardy and half - hardy, showing artistic and natural use of each plant — with several articles included from The Garden and chapters contributed by leading gardeners of the day, including Gertrude Jekyll, who contributed the chapter on "Colour in the Flower Garden".

This book was first published in 1883, with the last and definitive edition published in 1933. During Robinson's lifetime, the book found increasing popularity, with fifteen editions during his life. For fifty years, The English Flower Garden was considered a bible by many gardeners.

Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott (23 October 1865 – 10 February 1945), son of a wealthy Scottish landowner, was a British architect and artist. Through his long career he designed in a variety of styles, including a style derived from the Tudor, an Arts & Crafts style reminiscent of Voysey and later the Neo - Georgian.

Baillie Scott was born at Beards Hill, St Peters near Ramsgate, Kent, the second of ten children. He originally studied at the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester, but, having qualified in 1885, he decided to study architecture instead. He studied briefly in Bath, but his architectural development was especially marked by the 12 years he spent living in the Isle of Man. The first four years of this time he lived at Alexander Terrace, Douglas. In 1893, he and his family moved to Red House, Victoria Road, Douglas, which he had designed.

At the beginning of his career, Baillie Scott worked with Fred Saunders, with whom he had studied at the Isle of Man School of Art, which is also in Douglas. In May 1891, he was an art teacher. It was at the school of art that Baillie Scott and Archibald Knox became friends. He then left Saunders and set up his own business in 23 Athol Street, Douglas. In 1894 an article in The Studio he proposed a design having a high central hall with a galleried inglenook between the drawing and dining rooms and separated from them by folding screens. This hypothetical 'ideal house' brought in many commissions.

Baillie Scott developed his own unique Arts and Crafts style however, which progressed towards a simple form of architecture, relying on truth to material and function, and on precise craftsmanship.

Baillie Scott was known for the work he put into both the exterior and the interior, and its decoration. He produced nearly 300 buildings over the course of his career, including Red House, Isle of Man; Majestic Hotel, Onchan, Isle of Man; Blackwell, Bowness, Cumbria; Woodbury Hollow, Loughton, Essex; Winscombe House, Crowborough, Sussex; and Oakhams in 1942.

Baillie Scott died at the Elm Grove Hospital in Brighton. His gravestone in Edenbridge, Kent reads: "Nature he loved and next to nature art".