<Back to Index>

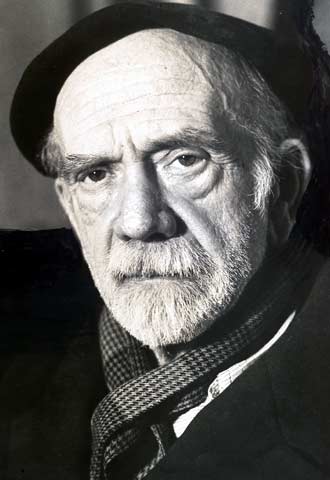

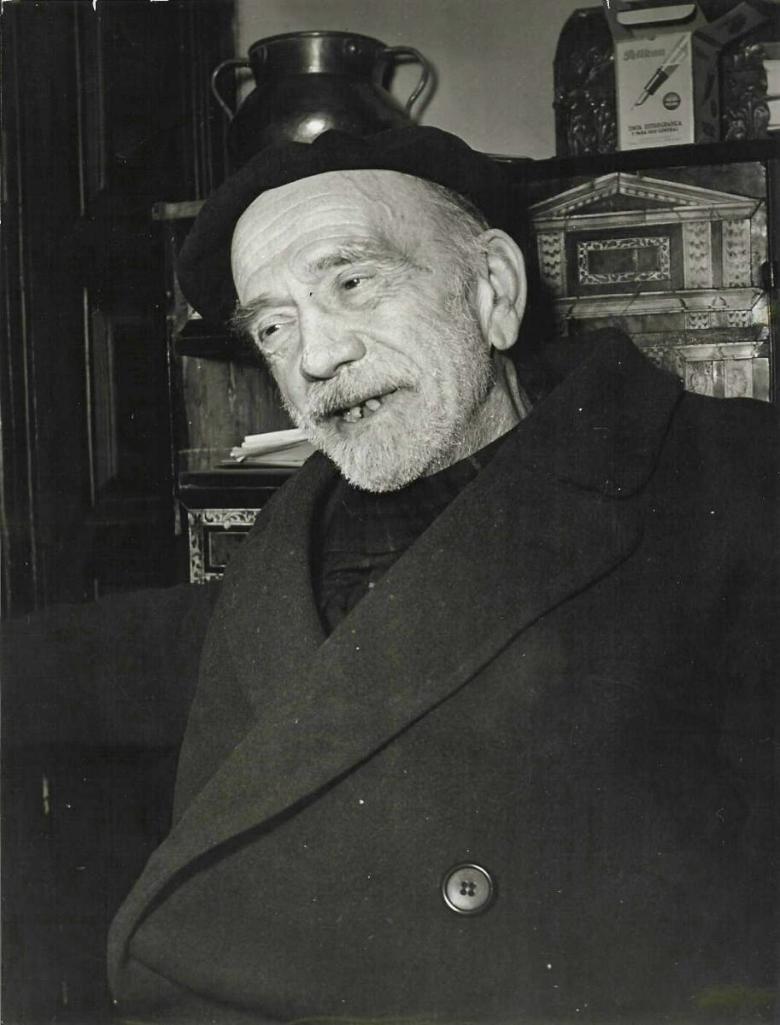

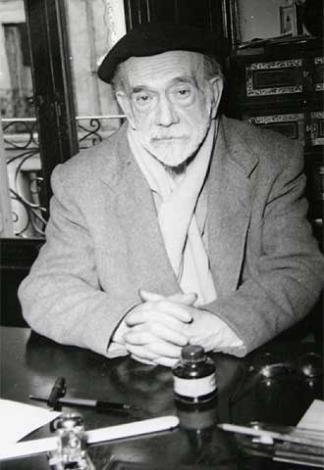

- Writer Pío Baroja y Nessi, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Pío Baroja y Nessi (December 28, 1872 – October 30, 1956) was a Spanish Basque writer, one of the key novelists of the Generation of '98. He was a member of an illustrious family, his brother Ricardo was a painter, writer and engraver, and his nephew Julio Caro Baroja, son of his younger sister Carmen, was a well known anthropologist.

The son of Serafin Baroja, a Basque writer and mining engineer, Pío was born in San Sebastian, Spain. Although educated as a physician, Baroja only practiced this profession briefly. As a matter of fact, he would use his student's memories - some of them he would consider terrible - as the raw material for his novel The Tree of Knowledge. He also managed the family bakery for a short time and ran unsuccessfully on two occasions for a seat at the Cortes (Spanish parliament) as a Radical Republican. Baroja's true calling, however, was always writing, which he began seriously at the age of 13.

His first novel -- La casa de Aizgorri (The House of Aizgorri, 1900) -- is part of a trilogy called La Tierra Vasca (The Basque Country, 1900 – 1909). This trilogy also includes El Mayorazgo de Labraz (The Lord of Labraz, 1903) which became one of his most popular novels in Spain.

However, he is best known internationally by another trilogy entitled La lucha por la vida (The Struggle for Life, 1922 – 1924) which offers a vivid depiction of life in Madrid's slums. John Dos Passos greatly admired these works and wrote about them.

Another major work -- Memorias de un Hombre de Acción (Memories of a Man of Action, 1913 – 1931) -- offers a depiction of one of his ancestors who lived in the Basque region during the Carlist uprising in the 19th century.

Another of his trilogies is called La mar (The sea) and comprises La estrella del capitán Tximista, Los Pilotos de altura, and Los mercaderes de esclavos. Baroja also wrote the biography of Juan Manuel Antonio Julian Van Halen, a mariner who lived in the late 18th century.

However, some believe his masterpiece to be El árbol de la ciencia (1911) (translated as The Tree of Knowledge), a pessimistic Bildungsroman that depicts the futility of the pursuit of knowledge and of life in general. The title is ironically symbolic: The more the chief protagonist Andres Hurtado learns about and experiences life, the more pessimistic he feels and the more futile his life seems.

In keeping with Spanish literary tradition, Baroja often wrote in a pessimistic, picaresque style. His deft portrayal of the characters and settings brought the Basque region to life much as Benito Pérez Galdós' works offered an insight into Madrid. Baroja's works were often lively, but could be lacking in plot and are written in an abrupt, vivid, yet impersonal style. Sometimes he is even accused of grammatical errors, which he never denied.

Baroja as a young man believed loosely in anarchistic ideals, as other members of the '98 Generation. However, later he would derive into simple admiration of men of action, somehow similar to Nietzsche's superman. His vitalistic vision of life - although pessimistic - led his novels, his ideas and his figure to be considered somehow a precursor of a kind of Spanish fascism. In any case, he was not loved by Catholic and traditionalist ideologists and his life was at risk during the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 39).

Ernest Hemingway was greatly influenced by Baroja, and told him when he visited him in October 1956, "Allow me to pay this small tribute to you who taught so much to those of us who wanted to be writers when we were young. I deplore the fact that you have not yet received a Nobel Prize, especially when it was given to so many who deserved it less, like me, who am only an adventurer".