<Back to Index>

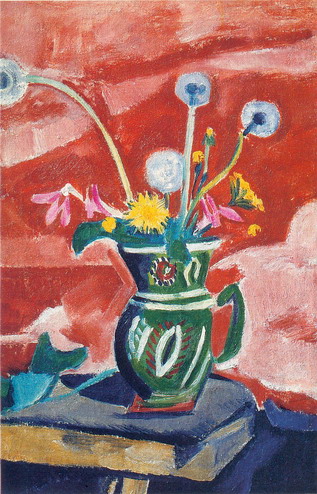

- Painter Olga Vladimirovna Rozanova, 1886

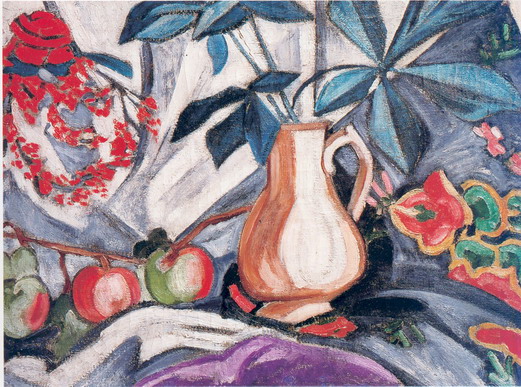

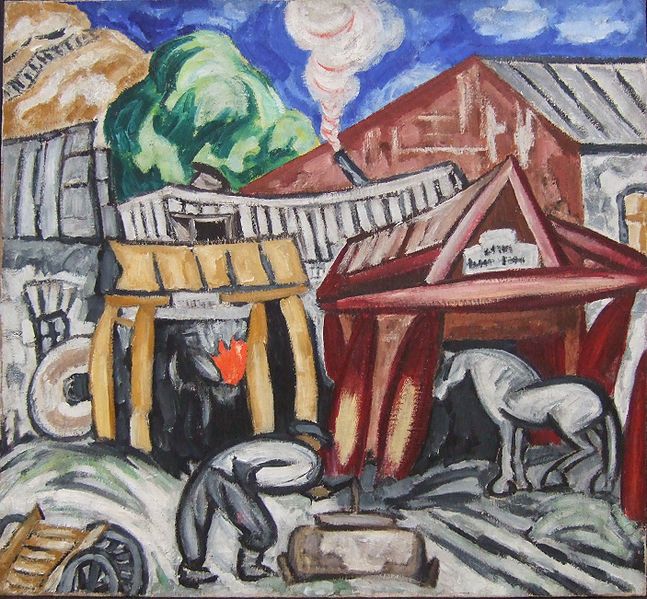

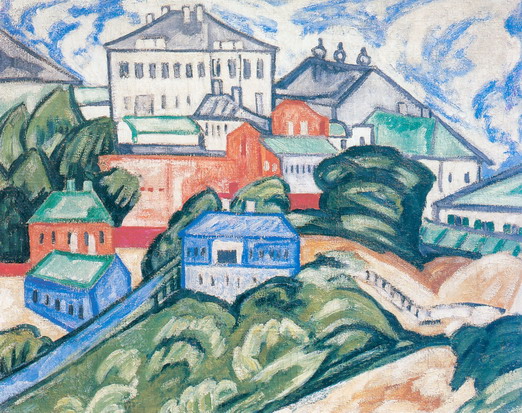

- Painter Nadezhda Andreeva Udaltsova, 1886

PAGE SPONSOR

Olga Vladimirovna Rozanova (also spelled Rosanova, Russian: Ольга Владимировна Розанова) (22 June, 1886 – 7 November, 1918, Moscow) was a Russian avant-garde artist painting in the styles of Suprematism, Neo-Primitivism and Cubo-Futurism.

Olga Rozanova was born in Melenki, a small town near Vladimir. Her father, Vladimir Rozanov, was a district police officer and her mother, Elizaveta Rozanova, was the daughter of an Orthodox priest. She was the family's fifth child; she had two sisters, Anna and Alevtina, and two brothers, Anatolii and Vladimir. Rozanova's father died in 1903, and her mother became the head of the household.

She graduated from the Vladimir Women's Gymnasium in 1904. Due to her interest in the avant-garde movement, she moved to Moscow to study painting.

After arriving in Moscow, she attended the Bolshakov Art School, where she worked under Nikolai Ulyanov and sculptor Andrey Matveev. She audited courses at the Stroganov School of Applied Art in 1907 but was not accepted for admission. After this, she trained in the private studio of Konstantin Yuon. From 1907 to 1910, fellow drawing and painting students studying in these private studios included Lyubov Popova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Aleksei Kruchenykh and Serge Charchoune. Unlike most of the other female avant-garde artists, Rozanova was the only one who did not study abroad to learn about European art.

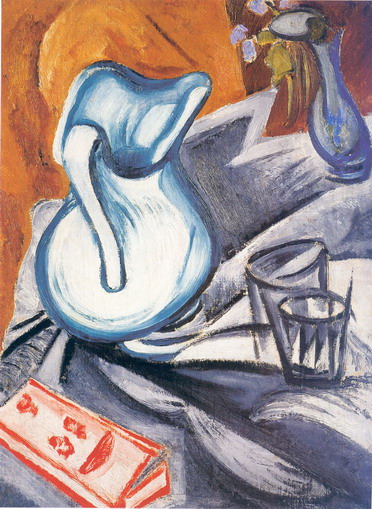

By 1910, she was fairly well known in Russian art circles. She moved to St. Petersburg and joined Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in 1911. She became one of the most active members of this organization, which organized art exhibitions, lectures, and discussions. Two of her canvases, Nature-morte and The Cafe debuted at the second Soyuz Molodyozhi exhibition in April 1911. She would submit her canvases to their group exhibitions until 1913. Razanova briefly studied at the art school of Elizabeta Zvantseva, which housed many Russian art nouveau artists. In January 1912, her two works, Portrait and Still-Life, appeared at the next Soyuz Molodyozhi exhibition in January 1912. This exhibition was the first appearance of the Donkey's Tail, a Moscow-based artistic group led by Mikhail Larionov. Rozanova later traveled to Moscow to try to establish joint projects between the two groups; these negotiations proved to be unsuccessful. Soyuz Molodyozhi disbanded in 1914.

From 1913 to 1914, Cubo-Futurist ideas appeared in her work, but she appears to have been especially inspired by Futurism. Of all of the Russian Cubo - Futurists, Rozanova's work most closely upholds the ideals of Italian Futurism. During Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's visit to Russia in 1914, he was very impressed with her work. Rozanova later exhibited four works in the First Free International Futurist Exhibition in Rome, which took place from April 13 to May 25, 1914. Other Russian artists featured in the exhibition included Alexander Archipenko, Nikolai Kulbin and Aleksandra Ekster.

She met the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh in 1912; he then introduced her to the Russian Futurist concept of zaum

(translated as "beyonsence") poetry, a language with no fixed meanings

and constant neologisms, which is probably used by birds. Rozanova would

write her own poetry in that style, and also illustrated books of zaum

poetry, two examples being A Little Duck's Nest of Bad Words and Explodity (both 1913). With Kruchenykh, she would invent a new kind of Futurist book, the samopismo, where the illustrations and the text would be literally connected.

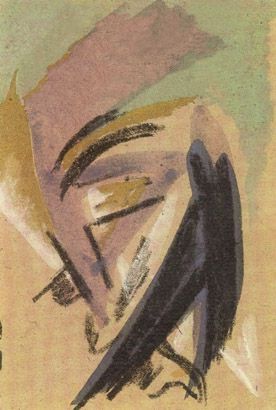

Rozanova joined the avant garde group Supremus that year, which was led by former fellow Cubo - Futurist Kazimir Malevich. By this time, her paintings has developed from the influences of Cubism and Futurism, and took an original departure into pure abstraction, where the composition is organized by the visual weight and relationship of color.

In the same year she exhibited at the 0,10 Exhibition, and, together with other Suprematist artists (Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Nina Genke, Liubov Popova, Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Ivan Puni and others) worked at the Verbovka Village Folk Center.

From 1917 to 1918 she created a series of non-objective paintings which she called tsv'etopis'. Her Non-objective composition, 1918 also known as Green stripe anticipates the flat picture plane and poetic nuancing of color of some Abstract Expressionists.

Rozanova also published literary works, which included the essay The Bases of the New Creation and the Reasons Why it is Misunderstood.

This was written in response to critics of modern art and held that the

world is a raw material - that it is the back of a mirror for the

unreceptive soul and a mirror of images for the reflective soul.

She maintained that the creation of pictures based on the "Abstract

Principle" constitute three stages: the intuitive principle; the

individual transformation of the visible; and, abstract creation. In her criticism of photography, Rozanova agreed with Oscar Wilde that photography is for the "servile artist".

She died of diphtheria at the age of 32 in Moscow in 1918, following a cold she contracted while working on preparations for the first anniversary of the October Revolution.

Her work is now in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Harvard Art Museums.

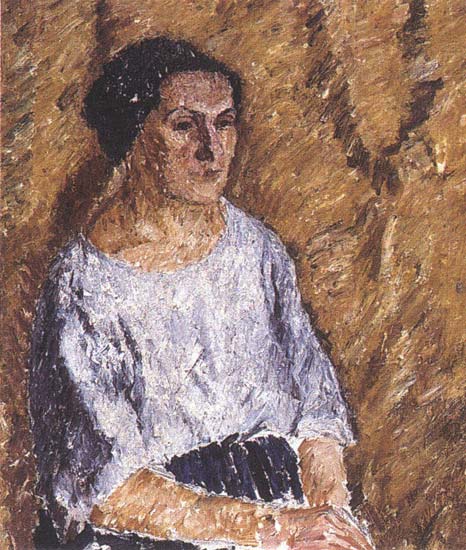

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova (Russian: Наде́жда Андре́евна Удальцо́ва, 29 December 1885 – 25 January 1961) was a Russian avant garde artist (Cubist, Suprematist), painter and teacher.

Nadezhda Udaltsova was born in the village of Orel, Russia, on 29 December 1885. When she was six, her family moved to Moscow, where she graduated from high school and began her artistic career. In September 1905 Udaltsova enrolled in the art school run by Konstantin Yuon and Ivan Dudin, where she studied for two years and met fellow students Vera Mukhina, Liubov Popova and Aleksander Vesnin. In the spring of 1908 she traveled to Berlin and Dresden, and upon her return to Russia, she unsuccessfully applied for admission to the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. She also married Alexander Udaltsov, her first husband, in 1908. In 1910 - 11, Udaltsova studied at several private studios, among them Vladimir Tatlin's. In 1912 - 13 she and Popova traveled to Paris to continue their studies under the tutelage of Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger and André Segonzac at Académie de La Palette. Udaltsova returned to Moscow in 1913 and worked in Vladimir Tatlin's studio together with Popova, Vesnin and others.

Udaltsova's professional debut was as a participant in a Jack of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow in the winter of 1914. But it was in 1915 that she really made her name as a Cubist artist, participating in three major exhibitions in that single year, including "Tramway V" (February), "Exhibition of Leftist Tendencies" (April), and "The Last Futurist Exhibition: 0.10" (December). Her paintings were subsequently collected and exhibited in the 1920s by the Tretiakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, and other venues as examples of Cubo - Futurism.

Under the influence of Tatlin, Udaltsova experimented with Constructivism, but eventually embraced the more painterly approach of the Suprematist movement. In 1916, she participated with other Suprematist artists in a Jack of Diamonds exhibition, and during that same time period she joined Kazimir Malevich's Supremus group. In 1915 - 1916, together with other suprematist artists (Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Liubov Popova, Nina Genke, Olga Rozanova, Ivan Kliun, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavskaya and others) worked at the Verbovka Village Folk Center.

Like many of her avant-garde contemporaries, Udaltsova embraced the October Revolution. In 1917, she was elected to the Club of the Young Leftist Federation of the Professional Union of Artists and Painters and began work in various state cultural institutions, including the Moscow Proletkult. In 1918, she joined the Free State Studios, first working as Malevich's assistant, and then heading up her own studio. She also collaborated with Aleksei Gan, Aleksei Morgunov, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Malevich on a newspaper entitled Anarkhiia (Anarchy). In 1919, Udaltsova contributed eleven works from the time she was working in Tatlin's studio to the "Fifth State Exhibition." She also married her second husband, the painter Alexander Drevin. When Vkhutemas, the Russian state art and technical school, was established in 1920, she was appointed professor and senior lecturer and would remain on staff until 1934. In 1920 she also became a member of the Institute of Artistic Culture (InKhuK) and actively participated in discussions there on the fate of easel art. However, when the Institute endorsed Constructivism and declared the end of easel painting, she resigned her membership in protest in 1921. In 1922 she participated in the First Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin.

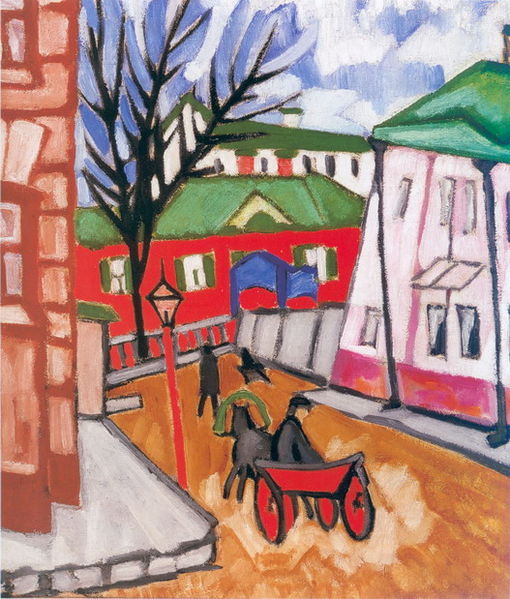

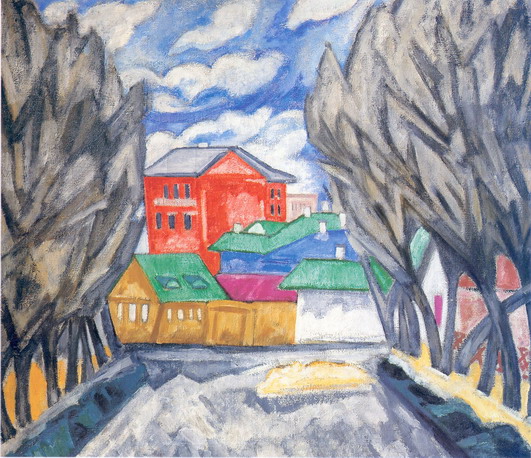

In the early 1920s, Udaltsova's work began to show a turn away from the radical avant-garde and a sensibility more aligned with artists associated with the Jack of Diamonds, among them Ilya Mashkov, Petr Konchalovsky and Aristarkh Lentulov, exhibiting her Fauvist portraits and landscapes alongside them at the Vkhutemas "Exhibition of Paintings" of 1923 and also at the Venice "Biennale" of 1924. She also continued to teach, including instruction in textile design at Vhkutemas and the Textile Institute in Moscow from 1920 until 1930.

Under the influence of Drevin, Udaltsova returned to nature and

began painting landscapes. Between 1926 and 1934 they traveled widely,

painting the Ural and Altai Mountains, as well as landscapes in Armenia

and Central Asia.

From 1927 to 1935, she contributed to national and international

exhibitions and participated with Drevin in joint exhibitions at the

Russian Museum (1928) and in Erevan, Armenia (1934).

In 1932 - 33, Udaltsova's contributions to the exhibition of "Artists of the RSFSR Over the Last Fifteen Years" were publicly criticized for so-called "formalist tendencies." In 1938 Alexander Drevin was arrested and executed by the NKVD, and Udaltsova became a persona non grata in the world of Soviet art. She was allowed a solo exhibition at the Moscow Union of Soviet Artists in 1945, and after Stalin's death, she contributed to a group exhibition at Moscow's House of the Artist in October 1958.

Udaltsova died in 1961 in Moscow.

The Udaltsova crater on Venus is named after her. Her son was the prominent Russian sculptor Andrei Drevin (1921 - 1996).