<Back to Index>

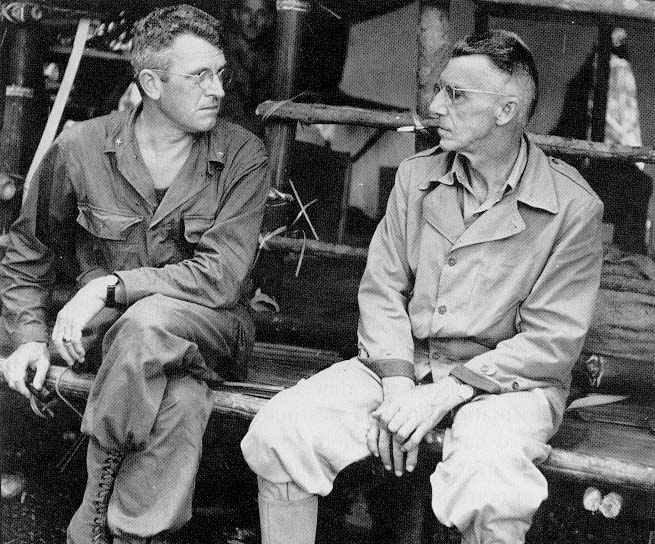

- General of the U.S. Army Joseph Warren Stilwell, 1883

- Lieutenant General of the U.S. Army Air Forces Claire Lee Chennault, 1893

- General of the U.S. Army Albert Coady Wedemeyer, 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

General Joseph Warren Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army four - star General known for service in the China Burma India Theater. His caustic personality was reflected in the nickname "Vinegar Joe". Although distrustful of his allies Stilwell showed himself to be a capable and daring tactician in the field but a lack of resources meant he was forced continually to improvise. He famously differed as to strategy, ground troops versus air power, with his subordinate, Claire Chennault, who had the ear of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. George Marshall acknowledged he had given Stilwell "one of the most difficult" assignments of any theater commander.

Stilwell was born on March 19, 1883, in Palatka, Florida, of patrician Yankee stock. His parents were Doctor Benjamin Stilwell and Mary A. Peene. Stilwell was an eighth generation descendant of an English colonist who arrived in America in 1638, whose descendants remained in New York up through the birth of Stilwell's father. Named for a family friend, as well as the doctor who delivered him, Joseph Stilwell, known as Warren by his family, grew up in New York, under a strict regimen from his father that included an emphasis on religion. Stilwell later admitted to his daughter that he picked up criminal instincts due to "...being forced to go to Church and Sunday School, and seeing how little real good religion does anybody, I advise passing them all up and using common sense instead."

Stilwell's rebellious attitude led him to a record of unruly behavior once he reached a post graduate level at Yonkers High School. Prior to this last year, Stilwell had performed meticulously in his classes, and had participated actively in football (as quarterback) and track. Under the discretion of his father, Stilwell was placed into a post graduate course following graduation, and immediately formed a group of friends whose activities ranged from card playing to stealing the desserts from the senior dance in 1900. This last event, in which an administrator was punched, led to the expulsions and suspensions for Stilwell's friends. Stilwell, meanwhile, having already graduated, was once again by his father's guidance sent to attend the United States Military Academy at West Point, rather than to proceed to Yale University as originally planned.

Despite missing the deadline to apply for Congressional appointment to the military academy, Stilwell gained entry through the use of family connections who knew President William McKinley. In his first year, Stilwell underwent hazing as a plebe that he referred to as "hell." While at West Point, Stilwell showed an aptitude for languages, such as French, in which he ranked first in his class during his second year. In the field of sports, Stilwell is credited with introducing basketball to the Academy, and participating in cross country running (as Captain), as well as playing on the varsity football team. At West Point he had two demerits for laughing during drill. Ultimately, Stilwell graduated from the academy, class of 1904, ranked 32nd in a class of 124 cadets. His son, Brigadier General Joseph, Jr., {West Point 1933} served in World War II, Korean War and Vietnam.

Stilwell later taught at West Point, and attended the Infantry Advanced Course and the Command and General Staff College. During World War I, he was the U.S. Fourth Corps intelligence officer and helped plan the St. Mihiel offensive. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his service in France.

Stilwell is often remembered by his sobriquet, "Vinegar Joe", which he acquired while a commander at Fort Benning, Georgia. Stilwell often gave harsh critiques of performance in field exercises, and a subordinate - stung by Joe's caustic remarks - drew a caricature of Stilwell rising out of a vinegar bottle. After discovering the caricature, Stilwell pinned it to a board and had the drawing photographed and distributed to friends. Yet another indication of his view of life was the motto he kept on his desk: Illegitimi non carborundum, a form of fractured Latin that translates as "Don't let the bastards grind you down."

Between the wars, Stilwell served three tours in China, where he became fluent in Chinese, and was the military attaché at the U.S. Legation in Beijing from 1935 to 1939. In 1939 and 1940 he was assistant commander of the 2nd Infantry Division and from 1940 to 1941 organized and trained the 7th Infantry Division at Fort Ord, California. It was there that his leadership style - which emphasized concern for the average soldier and minimized ceremonies and officious discipline - earned him the nickname of “Uncle Joe.”

Just prior to World War II, Stilwell was recognized as the top corps commander in the Army and was initially selected to plan and command the Allied invasion of North Africa. However, when it became necessary to send a senior officer to China to keep that country in the War, Stilwell was selected, over his personal objections, by President Franklin Roosevelt and his old friend, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. He became the Chief of Staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, served as the commander of the China Burma India Theater responsible for all Lend - Lease supplies going to China, and later was Deputy Commander of the South East Asia Command. Unfortunately, despite his status and position in China, he soon became embroiled in conflicts over U.S. Lend - Lease aid and Chinese political sectarianism.

Stilwell's assignment in the China - Burma - India Theater was a geographical administrative command on the same level as the commands of Dwight D. Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur. However, unlike other combat theaters, for example the European Theater of Operations, the CBI was never a "theater of operations" and did not have an overall American operational command structure. The China theater came under the operational command of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, commander of Nationalist Chinese forces, while the Burma India theater came under the operational command of the British (first India Command and later Allied South East Asia Command whose supreme commander was Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten). The British and the Chinese were ill equipped and more often than not on the receiving end of Japanese offensives. Chiang Kai-Shek was interested in conserving his troops and Allied Lend - Lease supplies for use against any sudden Japanese offensive, as well as against Chinese Communist forces in a later civil war. The Generalissimo's wariness increased after observing the disastrous Allied performance against the Japanese in Burma. After fighting and resisting the Japanese for five years, many in the Nationalist government felt that it was time for the Allies to assume a greater burden in fighting the war.

However, the first step to fighting the war for Stilwell was the reformation of the Chinese Army. These reforms clashed with the delicate balance of political and military alliances in China, which kept the Generalissimo in power. Reforming the army meant removing men who maintained Chiang's position as commander - in - chief. While he gave Stilwell technical overall command of some Chinese troops, Chiang worried that the new American led forces would become yet another independent force outside of his control. Since 1942, members of the Generalissimo's staff had continually objected to Chinese troops being used in Burma for the purpose, as they viewed it, of returning that country to British colonial control. Chiang therefore sided with General Claire Chennault's proposals that the war against the Japanese be continued largely using existing Chinese forces supported by air forces, something Chennault assured the Generalissimo was feasible. The dilemma forced Chennault and Stilwell into competition for the valuable Lend - Lease supplies arriving over the Himalayas from British controlled India — an obstacle referred to as "The Hump". George Marshall, in his biennial report covering the period of July 1, 1943 to June 30, 1945, acknowledged he had given Stilwell "one of the most difficult" assignments of any theater commander.

Arriving in Burma just in time to experience the collapse of the Allied defense of that country, which cut China off from all land and sea supply routes, Stilwell personally led his staff of 117 men and women out of Burma into Assam, India, on foot, marching at what his men called the 'Stilwell stride' - 105 paces per minute. Two of the men accompanying him, his aide Frank Dorn and the war correspondent, Jack Belden, wrote books about the walkout: Walkout with Stilwell in Burma (1971) and Retreat with Stilwell (1943), respectively. The Assam route was also used by other retreating Allied and Chinese forces.

In India, Stilwell soon became well known for his no-nonsense demeanor and disregard for military pomp and ceremony. His trademarks were a battered Army campaign hat, GI shoes, and a plain service uniform with no insignia of rank; he frequently carried a .30 Springfield rifle in preference to a sidearm. His hazardous march out of Burma and his bluntly honest assessment of the disaster captured the imagination of the American public: "I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.". However, Stilwell's derogatory remarks castigating the ineffectiveness of what he termed Limey forces, a viewpoint often repeated by Stilwell's staff, did not sit well with British and Commonwealth commanders. However, it was well known among the troops that Stilwell's disdain for the British was aimed toward those high command officers that he saw as overly stuffy and pompous.

After the Japanese occupied Burma, China was completely cut off from Allied aid and materiel except through the hazardous route of flying cargo aircraft over the Hump. Early on, the Roosevelt administration and the War Department had given priority to other theaters for U.S. combat forces, equipment and logistical support. With the closure of the Burma Road and the fall of Burma, it was realized that even replacing Chinese war losses would be extremely difficult. Consequently, the Allies' initial strategy was to keep Chinese resistance to the Japanese going by providing a lifeline of logistical and air support.

Convinced that the Chinese soldier was the equal of any given proper care and leadership, Stilwell established a training center (in Ramgarh, India, 200 miles west of Calcutta) for two divisions of Chinese troops from forces that had retreated to Assam from Burma. His effort in this regard met passive, sometimes active, resistance from the British, who feared that armed, disciplined Chinese would set an example for Indian insurgents, and from Chiang Kai-shek who did not welcome a strong military unit outside of his control. From the outset, Stilwell's primary goals were the opening of a land route to China from northern Burma and India by means of a ground offensive in northern Burma, so that more supplies could be transported to China, and to organize, equip and train a reorganized, reequipped, modernized and competent Chinese army that would fight the Japanese in the China - Burma - India theater (CBI). Stilwell argued that the CBI was the only area at that time where the possibility existed for the Allies of engaging large numbers of troops against their common enemy, Japan. Unfortunately, the huge airborne logistical train of support from the U.S.A. to British India was still being organized, while supplies being flown over the Hump were barely sufficient to maintain Chennault's air operations and replace some Chinese war losses, let alone equip and supply an entire army. Additionally, critical supplies intended for the CBI were being diverted due to various crises in other combat theaters. Of the supplies that made it over the Hump a certain percentage were diverted by Chinese (and American) personnel into the black market for their personal enrichment. As a result, most Allied commanders in India, with the exception of General Orde Wingate and his Chindit operations, were focused on defensive measures.

During this time in India, Stilwell became increasingly disenchanted with British forces, and did not hesitate to voice criticisms of what he viewed as hesitant or cowardly behavior. Ninety percent of the Chindit casualties were incurred in the last phase of the campaign from 17 May when they were under the direct command of Stilwell. The British view was quite different and they pointed out that over the period from 6 June to 27 June, Calvert's 77th Brigade, which lacked heavy weapons, took Mogaung and suffered 800 casualties (50%) among those of the brigade involved in the operation. Stilwell expected 77th Brigade to join the siege of Myitkyina but Michael Calvert, sickened by demands on his troops which he considered abusive, switched off his radios and withdrew to Stilwell's base. 111 Brigade, after resting, were ordered to capture a hill known as Point 2171. They did so, but were now utterly exhausted. Most of them were suffering from malaria, dysentery and malnutrition. On 8 July, at the insistence of the Supreme Commander, Admiral Louis Mountbatten, doctors examined the brigade. Of the 2200 men present from four and a half battalions, only 119 were declared fit. The Brigade was evacuated, although Masters sarcastically kept the fit men, "111 Company" in the field until 1 August.

The portion of 111 Brigade east of the Irrawaddy were known as Morris Force, after its commander, Lieutenant Colonel "Jumbo" Morris. They had spent several months harassing Japanese traffic from Bhamo to Myitkyina. They had then attempted to complete the encirclement of Myitkyina. Stilwell was angered that they were unable to do so, but Slim pointed out that Stilwell's Chinese troops (numbering 5,500) had also failed in that task. By 14 July, Morris Force was down to three platoons. A week later, they had only 25 men fit for duty. Morris Force was evacuated about the same time as 77th Brigade

Captain Charlton Ogburn, Jr., a U.S. Army Marauder officer, and Chindit brigade commanders John Masters and Michael Calvert later recalled that Stilwell's appointment of a staff officer specially detailed by him to visit subordinate commands in order to chastise their officers and men as being 'yellow'. In October 1943, after the Joint Planning Staff at GHQ India had rejected a plan by Stilwell to fly his Chinese troops into northern Burma, Field Marshal Wavell asked whether Stilwell was satisfied on purely military grounds that the plan could not work. Stilwell replied that he was. Wavell then asked what Stilwell would say to Chiang Kai-shek, and Stilwell replied "I shall tell him the bloody British wouldn't fight."

After Stilwell left the defeated Chinese troops that he had been given nominal command by Chiang Kai-shek (Chinese generals admitted later that they had considered Stilwell as an 'adviser' and sometimes took orders directly from Chiang), he escaped Burma in 1942, Chiang was outraged by what he saw as Stilwell's blatant abandonment of his best army without orders and began to question Stilwell's capability and judgment as a military commander. Chiang was also infuriated at Stilwell's strict control of U.S. lend lease supplies to China. But instead of confronting Stilwell or communicating his concerns to Marshall and Roosevelt when they asked Chiang to assess Stilwell's leadership after the Allied disaster in Burma, Chiang reiterated his "full confidence and trust" in the general while countermanding some orders to Chinese units issued by Stilwell in his capacity as Chief of Staff. An outraged Stilwell began to call Chiang "the little dummy" or "Peanut" in his reports to Washington, ("Peanut" originally being intended as a code name for Chiang in official radio messages) while Chiang repeatedly expressed his pent up grievances against Stilwell for his "recklessness, insubordination, contempt and arrogance" to U.S. envoys to China. Stilwell would press Chiang and the British to take immediate actions to retake Burma, but Chiang demanded impossibly large amounts of supplies before he would agree to take offensive action, and the British refused to meet their previous pledges to provide naval and ground troops due to Churchill's "Europe first" strategy. Eventually Stilwell began to complain openly to Roosevelt that Chiang was hoarding U.S. lend lease supplies because he wanted to keep Chinese Nationalist forces ready to fight the Communists under Mao Zedong after the end of the war with the Japanese, even though from 1942 to 1944 98 percent of U.S. military aid over the Hump had gone directly to the 14th Air Force and U.S. military personnel in China.

Stilwell also continually clashed with Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, and apparently came to believe that the British in India were more concerned with protecting their colonial possessions than helping the Chinese fight the Japanese. In August 1943, as a result of constant feuding and conflicting objectives of British, American and Chinese commands, along with the lack of a coherent strategic vision for the China Burma India (CBI) theater, the Combined Chiefs of Staff split the CBI command into separate Chinese and Southeast Asia theaters.

Stilwell was infuriated also by the rampant corruption of the Chiang regime. In his diary, which he faithfully kept, Stilwell began to note the corruption and the amount of money ($380,584,000 in 1944 dollars) being wasted upon the procrastinating Chiang and his government. The Cambridge History of China, for instance, also estimates that some 60% - 70% of Chiang's Kuomintang conscripts did not make it through their basic training, with some 40% deserting and the remaining 20% dying of starvation before full induction into the military. Eventually, Stilwell’s belief that the Generalissimo and his generals were incompetent and corrupt reached such proportions that Stilwell sought to cut off Lend - Lease aid to China. Stilwell even ordered Office of Strategic Services (OSS) officers to draw up contingency plans to assassinate Chiang Kai-shek after he heard Roosevelt's casual remarks regarding the possible defeat of Chiang by either internal or external enemies, and if this happened to replace Chiang with someone else to continue the Chinese resistance against Japan.

With the establishment of the new South East Asia Command in August 1943, Stilwell was appointed Deputy Supreme Allied Commander under Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. Taking command of various Chinese and Allied forces, including a new U.S. Army special operations formation, the 5307th Composite Unit (provisional) later known as Merrill's Marauders, Stilwell built up his Chinese forces for an eventual offensive in northern Burma. On December 21, 1943, Stilwell assumed direct control of planning for the invasion of Northern Burma, culminating with capture of the Japanese held town of Myitkyina. In the meantime, Stilwell ordered General Merrill and the Marauders to commence long-range jungle penetration missions behind Japanese lines after the pattern of the British Chindits. In February 1944, three Marauder battalions marched into Burma. Though Stilwell was at the Ledo Road front when the Marauders arrived at their jump-off point, the general did not walk out to the road to bid them farewell.[37]

In April 1944, Stilwell launched his final offensive to capture the Burmese city of Myitkyina. In support of this objective, the Marauders were ordered to undertake a long flanking maneuver towards the town, involving a grueling 65 mile jungle march. Having been deployed since February in combat operations in the jungles of Burma, the Marauders were seriously depleted and suffering from both combat losses and disease, and lost additional men while en route to the objective. A particularly devastating scourge was a severe outbreak of amoebic dysentery, which erupted shortly after the Marauders linked up with X Force. By this time, the men of the Marauders had openly begun to suspect Stilwell's commitment to their welfare. Despite their sacrifices, Stilwell appeared unconcerned about their losses, and had rejected repeated requests for medals for individual acts of heroism. Initial promises of a rest and rotation were ignored; the Marauders were not even air dropped replacement uniforms or mail until late April.

On May 17, 1,310 remaining Marauders attacked Myitkyina airfield in concert with elements of two Chinese infantry regiments and a small artillery contingent. The airfield was quickly taken, but the town, which Stilwell's intelligence staff had believed to be lightly defended, was garrisoned by significant numbers of well equipped Japanese troops, who were steadily being reinforced. A preliminary attack on the town by two Chinese regiments was thrown back with heavy losses. The Marauders did not have the manpower to immediately overwhelm Myitkyina and its defenses; by the time additional Chinese forces arrived and were in a position to attack, Japanese forces totaled some 4,600 fanatical Japanese defenders.

During the Myitkyina siege, which took place during the height of the monsoon season, Marauders' second - in - command, Col. Hunter, as well as the unit's regimental and battalion level surgeons, had urgently recommended that the entire 5307th be relieved of duty and returned to rear areas for rest and recovery. By this time, most of the men had fevers and continual dysentery, forcing the men to cut the seats out of their uniform trousers in order to fire their weapons and relieve themselves simultaneously. Stilwell rejected the evacuation recommendation, though he did make a front line inspection of the Myitkyina lines. Afterwards, he ordered all medical staff to stop returning combat troops suffering from disease or illness, and instead return them to combat status, using medications to keep down fevers. The feelings of many Marauders towards General Stilwell at that time were summed up by one soldier, who stated, "I had him [Stilwell] in my sights. I coulda' squeezed one off and no one woulda' known it wasn't a Jap who got that son of a bitch."

Stilwell also ordered that all Marauders evacuated from combat due to wounds or fever first submit to a special medical 'examination' by doctors appointed by his headquarters staff. These examinations passed many ailing soldiers as fit for duty; Stilwell's staff roamed hospital hallways in search of any Marauder with a temperature lower than 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Some of the men who were passed and sent back into combat were immediately re-evacuated as unfit at the insistence of forward medical personnel. Later, Stilwell's staff placed blame on Army medical personnel for overzealously interpreting Stilwell's return - to - duty order.

During the Myitkyina siege, Japanese soldiers resisted fiercely, generally fighting to the last man. As a result, Myitkyina did not fall until August 4, 1944, after Stilwell was forced to send in thousands of Chinese reinforcements, though Stilwell was pleased that the objective had at last been taken (his notes from his personal diary contain the notation, "Boy, will this burn up the Limeys!"). Later, Stilwell blamed the length of the siege, among other things, on British and Gurkha Chindit forces for not promptly responding to his demands to move north in an attempt to pressure Japanese troops. This was in spite of the fact that the Chindits themselves had suffered grievous casualties in several fierce pitched battles with Japanese troops in the Burmese jungles, along with losses from illness and combat exhaustion. Stilwell also had not kept his British allies clearly informed of his force movements, nor coordinated his offensive plans with those of General Slim.

Bereft of further combat replacements for his hard pressed Marauder battalions, Stilwell felt he had no choice but to continue offensive operations with his existing forces, using the Marauders as 'the point of the spear' until they had either achieved all their objectives, or were wiped out. He was also concerned that pulling out the Marauders, the only U.S. ground unit in the campaign, resulted in charges of favoritism, forcing him to evacuate the exhausted Chinese and British Chindit forces as well. When General William Slim, commander of British and Commonwealth forces in Burma, informed Stilwell that his men were exhausted and should be withdrawn, Stilwell rejected the idea, insisting that his subordinate commanders simply did not understand enlisted men and their tendency to magnify physical challenges. Having made his own 'long march' out of Burma under his own power using jungle trails, Stilwell found it difficult to sympathize with those who had been in combat in the jungle for months on end without relief. In retrospect, his statements at the time revealed a lack of understanding of the limitations of lightly equipped unconventional forces when used in conventional roles. Myitkyina and the dispute over evacuation policy precipitated a hurried Army Inspector General investigation, followed by U.S. congressional committee hearings, though no disciplinary measures were taken against General Stilwell for his decisions as overall commander.

Only a week after the fall of Myitkyina in Burma, the 5307th Marauder force, down to only 130 combat effective men (out of the original 2,997), was disbanded.

One of the most significant conflicts to emerge during the war was between General Stilwell and General Claire Lee Chennault, the commander of the famed "Flying Tigers" and later air force commander. As adviser to the Chinese air forces, Chennault proposed a limited air offensive against the Japanese in China in 1943 using a series of forward air bases. Stilwell insisted that the idea was untenable, and that any air campaign should not begin until fully fortified air bases supported by large infantry reserves had first been established. Stilwell then argued that all air resources be diverted to his forces in India for an early conquest of North Burma.

Following Chennault's advice, Generalissimo Chiang rejected the proposal; British commanders sided with Chennault, aware they could not launch a coordinated Allied offensive into Burma in 1943 with the resources then available. During the summer of 1943, Stilwell's headquarters concentrated on plans to rebuild the Chinese Army for an offensive in northern Burma, despite Chiang's insistence on support to Chennault's air operations. Stilwell believed that after forcing a supply route through northern Burma by means of a major ground offensive against the Japanese, he could train and equip thirty Chinese divisions with modern combat equipment. A smaller number of Chinese forces would transfer to India, where two or three new Chinese divisions would also be raised. This plan remained only theoretical at the time, since available airlift capacity for deliveries of supplies to China over the Hump barely sustained Chennault's air operations, and were wholly insufficient to equip a new Chinese Army.

In 1944, the Japanese launched the counter offensive, Operation Ichi - Go, quickly overrunning Chennault's forward air bases and proving Stilwell partially correct. However, by this time, Allied supply efforts via the Hump airlift were steadily improving in tonnage supplied per month; with the replacement of Chinese war losses, Chennault now saw little need for a ground offensive in northern Burma in order to reopen a ground supply route to China. This time, augmented with increased military equipment and additional troops, and concerned about defense of the approaches to India, British authorities sided with Stilwell.

In coordination with a southern offensive by Nationalist Chinese forces under General Wei Li-huang, Allied troops under Stilwell's command launched the long awaited invasion of northern Burma; after heavy fighting and casualties, the two forces linked up in January 1945. Stilwell's strategy remained unchanged: opening a new ground supply route from India to China would allow the Allies to equip and train new Chinese army divisions for use against the Japanese. The new road network, later called the Ledo Road, would link the northern end of the Burma Road as the primary supply route to China; Stilwell's staff planners had estimated the route would supply 65,000 tons of supplies per month. Using these figures, Stilwell argued that the Ledo Road network would greatly surpass the tonnage being airlifted over the Hump. General Chennault doubted that such an extended network of trails through difficult jungle could ever match the tonnage that could be delivered with modern cargo transport aircraft then deploying in-theater. Progress on the Ledo Road was slow, and could not be completed until the linkup of forces in January 1945.

In the end, Stilwell's plan to train and modernize thirty Chinese divisions in China (as well as two or three divisions from forces already in India) was never fully realized. As Chennault predicted, supplies carried over the Ledo Road at no time approached tonnage levels of supplies airlifted monthly into China via the Hump. In July 1945, 71,000 tons of supplies were flown over the Hump, compared to only 6,000 tons using the Ledo Road, and the airlift operation continued in operation until the end of the war. By the time supplies were flowing over the Ledo Road in large quantities, operations in other theaters had shaped the course of the war against Japan. Stilwell's drive into North Burma, however, allowed Air Transport Command to fly supplies into China more quickly and safely by allowing American planes to fly a more southerly route without fear of Japanese fighters. American airplanes no longer had to make the dangerous venture over the Hump, increasing the delivery of supplies from 18,000 tons in June 1944, to 39,000 tons in November 1944. On August 1, 1945 a plane crossed the hump every one minute and 12 seconds.

In acknowledgment of Stilwell's efforts, the Ledo Road was later renamed the Stilwell Road by Chiang Kai-shek.

With the rapid deterioration of the China front after Japanese launched Operation Ichi - Go in 1944, Stilwell saw this as an opportunity to gain full command of all Chinese armed forces, and convinced Marshall to have Roosevelt send an ultimatum to Chiang threatening to end all American aid unless Chiang "at once" place Stilwell "in unrestricted command of all your forces." An exultant Stilwell immediately delivered this letter to Chiang despite pleas from Patrick Hurley, Roosevelt's special envoy in China, to delay delivering the message and work on a deal that would achieve Stilwell's aim in a manner more acceptable to Chiang. Seeing this act as a move toward the complete subjugation of China, Chiang gave a formal reply in which he said that Stilwell must be replaced immediately and he would welcome any other qualified U.S. general to fill Stilwell's position.

On October 19, 1944, Stilwell was recalled from his command by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Partly as a result of controversy concerning the casualties suffered by U.S. forces in Burma and partly due to continuing difficulties with the British and Chinese commanders, Stilwell's return to the United States was not accompanied by the usual ceremony. Upon arrival, he was met by two Army generals at the airport, who told him that he was not to answer any media questions about China whatsoever.

Stilwell was replaced by General Albert C. Wedemeyer, who received a telegram from General Marshall on October 27, 1944 directing him to proceed to China to assume command of the China theater and replace General Stilwell. Wedemeyer later recalled his initial dread over the assignment, as service in the China theater was considered a graveyard for American officials, both military and diplomatic. When Wedemeyer actually arrived at Stilwell’s headquarters after Stilwell’s dismissal, Wedemeyer was dismayed to discover that Stilwell had intentionally departed without seeing him, and did not leave a single briefing paper for his guidance, though departing U.S. military commanders habitually greeted their replacement in order to thoroughly brief them on the strengths and weaknesses of headquarters staff, the issues confronting the command, and planned operations. Searching the offices, Wedemeyer could find no documentary record of Stilwell's plans or records of his former or future operations. General Wedemeyer then spoke with Stilwell’s staff officers but learned little from them because Stilwell, according to the staff, kept everything in his “hip pocket”.

Despite prompting by the news media, Stilwell never complained about his treatment by Washington or by Chiang. He later served as Commander of Army Ground Forces, U.S. Tenth Army Commander in the last few days of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, and as U.S. Sixth Army Commander.

In November, he was appointed to lead a "War Department Equipment Board" in an investigation of the Army's modernization in light of its recent experience. Among his recommendations was the establishment of a combined arms force to conduct extended service tests of new weapons and equipment and then formulate doctrine for its use, and the abolition of specialized anti - tank units. His most notable recommendation was for a vast improvement of the Army's defenses against all airborne threats, including ballistic missiles. In particular, he called for "guided interceptor missiles, dispatched in accordance with electronically computed data obtained from radar detection stations."

Stilwell died of stomach cancer on October 12, 1946 at the Presidio of San Francisco, while still on active duty. His ashes were scattered on the Pacific Ocean, and a cenotaph was placed at the West Point Cemetery. Among his military decorations are the Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal with one Oak Leaf Cluster, the Legion of Merit degree of Commander, the Bronze Star and the Combat Infantryman Badge (this last award was given to him as he was dying from stomach cancer).

Stilwell’s home, built in 1933 - 1934 on Carmel Point, Carmel, California, remains a private home. A number of streets, buildings and areas across the country have been named for Stilwell over the years, including Joseph Stilwell Middle School in Jacksonville, Florida. The Soldiers’ Club he envisioned in 1940 (a time when there was no such thing as a soldiers’ club in the Army) was completed in 1943 at Fort Ord on the bluffs overlooking Monterey Bay. Many years later the building was renamed “Stilwell Hall” in his honor, but because of the erosion of the bluffs over the decades, the building was taken down in 2003. Stilwell's former residence in Chongqing - a city along the Yangtze River to which Chiang's government retreated after being forced from Nanjing by Japanese troops - has now been converted to the General Joseph W. Stilwell Museum in his honor.

In her book Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911 - 45, Barbara Tuchman wrote Stilwell was sacrificed as a political expedient due to his inability to get along with his allies in the theater. Stilwell's removal was certainly a result of substantial political pressure by Chiang through diplomatic means and using influential American friends who supported Chiang's government. One such group, informally called the "China Lobby", included Time publisher Henry Luce and his wife Clare Boothe Luce as well as J. Edgar Hoover.

Some historians, such as David Halberstam in his final book, The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War, have theorized Roosevelt was concerned Chiang would sign a separate peace with Japan, which would free many Japanese divisions to fight elsewhere, and Roosevelt wanted to placate Chiang. The power struggle over the China Theater that emerged between Stilwell, Chennault and Chiang reflected the American political divisions of the time.

A very different interpretation of events suggests that Stilwell, pressing for his full command of all Chinese forces, had made diplomatic inroads with the Chinese Communist Red Army commanded by Mao Zedong. He bypassed his theater commander Chiang Kai-Shek and had gotten Mao to agree to follow an American commander. His confrontational approach in the power struggle with Chiang ultimately led to Chiang's determination to have Stilwell recalled to the United States.

Stilwell, a "soldier's soldier", was nonetheless an old school American infantry officer unable to appreciate the creative developments in warfare brought about by World War II - -including strategic air power and the use of highly trained infantrymen as jungle guerrilla fighters. His disagreements with the equally acerbic Gen. Claire L. Chennault came about not only because Chennault overvalued the effectiveness of air power against massed ground troops -- a fact proven by the fall of the 14th Air Force bases in eastern China (Hengyang, Kweilin, etc.) in the Japanese eastern China offensive of 1944 -- but because Stilwell mistakenly believed air power's sole use lay in support for ground troops. Stilwell, in fact, clashed with almost every other officer in the theater with novel ideas, including Orde Wingate, who led the Chindits, and Col. Charles Hunter, officer in charge of Merrill's Marauders. Stilwell could neither appreciate the toll constant jungle warfare took on even the most highly trained troops, nor the incapacity of lightly armed, fast moving jungle guerrilla forces to dislodge heavily armed regular infantry supported by artillery. Accordingly, Stilwell abused both Chindits and Marauders, and earned the contempt of both units and their commanders.

In other respects, however, Stilwell was a skilled tactician in U.S. Army's land warfare tradition, with a deep appreciation of the logistics required of campaigning in rough terrain (hence his dedication to the Ledo Road project, for which he received several awards, including the Distinguished Service Cross and the US Army Distinguished Service Medal). Stilwell was also a pretty good judge of men. His derogatory evaluation of Chiang Kai-Shek proved accurate, as did his appraisal of the leadership qualities and field value of Mao Zedong and his communist troops. The trust Stilwell placed in men of real insight and character in understanding China, particularly the China Hands, John Stewart Service and John Paton Davies, Jr., confirms this assessment.

Arguably, had Stilwell been given the number of American regular infantry divisions he had continually requested, the American experience in China and Burma would have been very different. Certainly, his Army peers, Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Gen. George Marshall had the highest respect for his abilities, and both saw he replaced Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner as commander of Tenth U.S. Army at Okinawa after the latter's death. During the last year of the war, however, the U.S. was strained to meet all its military obligations, and cargo aircraft diverted to supply Stilwell, the 14th Air Force, and the Chinese in the East left air drop - dependent campaigns in the West, such as Operation Market Garden, woefully short of aircraft. The destruction of 1st Airborne at Arnhem was one result of these competing demands.

Although Chiang succeeded in removing Stilwell, the public relations damage suffered by his Kuomintang regime was irreparable. Right before Stilwell's departure, New York Times drama critic - turned - war correspondent Brooks Atkinson interviewed him in Chungking and wrote, "The decision to relieve General Stilwell represents the political triumph of a moribund, anti - democratic regime that is more concerned with maintaining its political supremacy than in driving the Japanese out of China. The Chinese Communists... have good armies that they are claiming to be fighting guerrilla warfare against the Japanese in North China — actually they are covertly or even overtly building themselves up to fight Generalissimo's government forces... The Generalissimo naturally regards these armies as the chief threat to the country and his supremacy... has seen no need to make sincere attempt to arrange at least a truce with them for the duration of the war... No diplomatic genius could have overcome the Generalissimo's basic unwillingness to risk his armies in battle with the Japanese." Atkinson, who had visited Mao in Yenan, saw the Communist Chinese forces as a democratic movement (after Atkinson visited Mao, his article on his visit was titled Yenan: A Chinese Wonderland City), and the Nationalists in turn as hopelessly reactionary and corrupt; this view was shared by many of the U.S. press corps in China at the time. The negative image of the Kuomintang in America played a significant factor in Harry Truman's decision to end all U.S. aid to Chiang at the height of the Chinese civil war, a war that resulted in the communist revolution in China and Chiang's retreat to Taiwan.

Lieutenant General Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958), was an American military aviator. A contentious officer, he was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fight - interceptor aircraft during the 1930s when the U.S. Army Air Corps was focused primarily on high altitude bombardment. Chennault retired in 1937, went to work as an aviation trainer and adviser in China, and commanded the "Flying Tigers" during World War II, both the volunteer group and the uniformed units that replaced it in 1942. His family name is French and is normally pronounced shen-o. However, his family being Americanized, the name was instead pronounced "shen-AWLT."

Claire Lee Chennault was born in Commerce, Texas, to John Stonewall Jackson Chennault and Jessie (nėe Lee) Chennault. He was reared in the Louisiana towns of Gilbert and Waterproof. He began misrepresenting his year of birth as 1890, possibly because he was too young to attend college after he graduated from high school, so his father added three years to his age. The 1900 US Census record from Franklin Parish, LA, Ward 2 states that C L Chennault was six years of age in 1900, with a younger brother, aged three.

Chennault attended Louisiana State University between 1909 and 1910 and received ROTC training (Claire). At the onset of World War I, Chennault graduated from Officer's School at Fort Benjamin Harrison, and was transferred to the Aviation Division of the Army Signal Corps. He learned to fly in the Air Service during World War I, graduated from pursuit pilot training at Ellington Field, Texas, on April 23, 1922, and remained in the service after it became the Air Corps in 1926. Chennault became Chief of Pursuit Section at Air Corps Tactical School in the 1930s.

Into the mid 1930s Chennault led and represented the 1st Pursuit Group of the Army Air Corps aerobatic team the "Three Musketeers" based in Montgomery, Alabama — the group performed at the 1928 National Air Races. Later, in 1932, as a pursuit aviation instructor at Maxwell Field, Chennault reorganized the team under the name "The Men on the Flying Trapeze".

Poor health and disputes with superiors led Chennault to resign from the service on April 30, 1937. He then went to China and joined a small group of American civilians training Chinese airmen. When the Sino - Japanese War (1937 – 1945) broke out in July, he served as "air adviser" to Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalist Government leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, working through the generalissimo's wife, Soong May-ling. Chennault participated in planning operations, observed the Chinese Air Force in combat from a Curtiss Hawk 75, and helped organize the so called "International Squadron" of foreign mercenary aviators. However, as Soviet air units increasingly flowed into China from the beginning of 1938, Chennault was sent to Kunming to head up a new training effort.

Chennault arrived in China on June 1937, after retiring from the United States Army Air Corps with the rank of captain. He had a three month contract at a salary of $1,000 per month, with the mission of making a survey of the Chinese Air Force. Soong May-ling, or "Madame Chiang" as she was known to Americans, was in charge of the Aeronautical Commission and thus became Chennault's immediate supervisor. Upon the outbreak of the Second Sino - Japanese War that August, Chennault became Chiang Kai-shek's chief air adviser, helping to train Chinese Air Force bomber and fighter pilots, sometimes flying scouting missions in an export Curtiss H-75 fighter, and organizing the "International Squadron" of mercenary pilots.

Increasingly, however, Soviet bomber and fighter squadrons took over from China's battered units, and in the summer of 1938 Chennault went to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province in Western China, to train a new Chinese Air Force from an American mold.

On October 19, 1939, Chennault boarded Pan American Airways "California Clipper" (Boeing B-314; NC18602) at the Pan American Airways terminal in Hong Kong. Chennault was on a special mission for Chiang Kai-shek. The California Clipper made a number of stops in the Pacific that included Manila (October 21) and Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii (October 25), eventually arriving at Treasure Island, San Francisco CA (October 26). Traveling with Chennault were four Chinese government officials: Mr. Shiao-down Chiang, Mr. Liu Yu-Wan, Mr. Tuan-Sheng Chien, and Mr. Ken-Sen Chow. Four of these passengers listed their place of origination as Kunming, China, and Mr. Chow as Kaiting, China.

By 1940, seeing that the Chinese Air Force had collapsed, because of ill trained Chinese pilots and shortage of equipment, Chiang Kai-shek sent Chennault to the United States to meet with Dr. T.V. Soong in Washington DC, with the following directed purpose: to get as many fighter planes, bombers and transports as possible, plus all the supplies needed to maintain them and the pilots to fly the aircraft. With Chennault, the Chinese President ordered Chinese Air Force General Pang-Tsu Mow to assist Chennault at the Chinese Embassy in Washington, DC. Together, they departed on Tuesday, October 15, 1940, from Chungking (Chongqing), China, arriving at the Port of Hong Kong where they boarded American Clipper (Boeing B-314, Pan American Airlines No. NC 18606, Captain J. Chase), on Friday, November 1, 1940; arriving Port of San Francisco at Treasure Island, on Thursday, November 14, 1940. They reported to the Chinese Ambassador to the United States Hu Shih on a mission that would ultimately conclude negotiations for the creation of an American Volunteer Group of pilots and mechanics to serve in China. How to obtain the shopping list of aircraft, aviation supplies, volunteers and funds for the Bank of China were discussed in a meeting held at the home of Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Saturday afternoon, December 21, 1940, with Captain Chennault, Dr. T.V. Soong and General Pang-Tsu Mow. He departed Hong Kong on June 19, 1940 aboard Pan American Airways Honolulu Clipper; departed Manila, Philippines, on June 21; arrived at Treasure Island, San Francisco, California, on June 25; departed from Naval Auxiliary Air Facility Mills Field, Oakland, California, at 7:00 pm, June 25 aboard a United Airlines DC-3; arriving at Washington National Airport, June 26. This mission was focused on establishing bank loans between the U.S. government and the Bank of China. Traveling with Dr. Soong were three other Chinese government bank officials: Chu-Chen Lee, Fu-Chen Chang, Chien-Hung Chang. By late July 1940, Dr. Soong was able to obtain concessions from the U.S. government for two $50 million loans (to stabilize Chinese financial market; to purchase war material). On Friday, April 25, 1941, the United States and China formally signed a $50 million stabilization agreement to support the Chinese currency. Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau signed for the United States, and Dr. T.V. Soong and Dr. Lee Kan both signed for the Chinese government with the Chinese Ambassador to the United States Dr. Hu Shih present.

By Monday afternoon, December 23, upon approval by the War Department, State Department and the President of the United States, an agreement was reached to provide China the 100 P-40B Tomahawk aircraft (redesignated P-40Cs after their modifications for overseas service) that were originally scheduled for shipment to Great Britain but cancelled due to the Tomahawk's inferior flight performance against German fighters. With an agreement reached, General Pang-Tsu Mow returned to China aboard SS Lurline; departing out of the Port of Los Angeles Friday morning, January 24, 1941. Chennault followed shortly after with a promise from the War Department and President Roosevelt to be delivered to Chiang Kai-shek that several shipments of P-40C fighters were forthcoming along with pilots, mechanics and aviation supplies. And, Dr. Soong began negotiations for an increase in financial aid with U.S. Secretary of Commerce and Federal Loan Administrator Jesse H. Jones on Thursday, October 17, 1940.

President Roosevelt then sent Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks to the Chinese under the American Lend - Lease program. Chennault also was able to recruit some 300 American pilots and ground crew, posing as tourists, who were adventurers or mercenaries, not necessarily idealists out to save China. But under Chennault they developed into a crack fighting unit, always going against superior Japanese forces. They became the symbol of America's military might in Asia.

Just weeks after the Japanese air Attack on Pearl Harbor (Sunday morning, December 7, 1941), the first news reports released to the public pertaining to Claire Chennault's war exploits occurred on December 20, 1941 when senior Chinese officials in Chungking that Saturday evening released his name to United Press International reporters to commemorate the first aerial attack made by the international air force called the American Volunteer Group (AVG). These American flyers encountered 10 Japanese aircraft heading to raid Kunming, and successfully shot down four of the raiders. Thus, Colonel Claire Chennault became America's first military leader to be publicly recognized for striking a blow against the Japanese military forces. This American public fame would last four months until the Doolittle Raid led by Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, United States Army Air Forces. In 1948, Chennault would make a controversial claim that General Clayton Bissell had not informed him of the upcoming raid, and that the raiders took unnecessary casualties because of it.

Based primarily out of Rangoon, Burma and Kunming, Yunnan, Chennault's 1st American Volunteer Group (AVG) – better known as the "Flying Tigers" – began training in August 1941 and fought the Japanese for seven months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Chennault's three squadrons used P-40s, and his tactics of "defensive pursuit," formulated in the years when bombers were actually faster than intercepting fighter planes, to guard the Burma Road, Rangoon, and other strategic locations in Southeast Asia and western China against Japanese forces. As the commander of the Chinese Air Force flight training school at Yunnan-yi, west of Kunming, Chennault also made a great contribution by training a new generation Chinese fighter pilots.

The Flying Tigers were formally incorporated into the United States Army Air Forces in 1942. Prior to that, Chennault had rejoined the Army with the rank of colonel. He was later promoted to brigadier general and then major general, commanding the Fourteenth Air Force.

The first magazine photo coverage of Claire Chennault took place within Life magazine in the Monday, August 10, 1942, issue. The first Time magazine photo coverage of Claire Chennault took place in its Monday, December 6, 1943, issue.

Throughout the war Chennault was engaged in a bitter dispute with the American ground commander, General Joseph Stilwell. Chennault believed that the Fourteenth Air Force, operating out of bases in China, could attack Japanese forces in concert with Nationalist Chinese troops. For his part, Stilwell wanted air assets diverted to his command to support the opening of a ground supply route through northern Burma to China. This route would provide supplies and new equipment for a greatly expanded Nationalist force of twenty to thirty modernized divisions. Chiang Kai-shek favored Chennault's plans, since he was suspicious of British colonial interests in Burma and was not prepared to begin major offensive operations against the Japanese. He was also concerned about alliances with semi - independent generals supporting the Nationalist government, and was concerned that a major loss of military forces would enable his Communist Chinese adversaries to gain the upper hand.

Good weather in November 1943 found the Japanese Army air forces ready to challenge Allied forces again, and they began night and day raids on Calcutta and the Hump bases while their fighters contested Allied air intrusions over Burma. In 1944, Japanese ground forces advanced and seized Chennault's forward bases. Slowly, however, the greater numbers and greater skill of the Allied air forces began to assert themselves. By mid 1944, Major General George E. Stratemeyer's Eastern Air Command dominated the skies over Burma; this superiority was never to be relinquished. At the same time, logistical support reaching India and China via the Hump finally reached levels permitting an Allied offensive into northern Burma.

Chennault had long argued for expansion of the airlift, doubting that any ground supply network through Burma could provide the tonnage needed to reequip Chiang's divisions. However, work on the Ledo Road overland route continued throughout 1944 and was completed in January 1945. Training of the new Chinese divisions commenced; however, predictions of monthly tonnage (65,000 per month) over the road were never achieved. By the time Nationalist armies began to receive large amounts of supplies via the Ledo Road, the war had ended. Instead, the airlift continued to expand until the end of the war, after delivering 650,000 tons of supplies, gasoline and military equipment.

Chennault, who, unlike Joseph Stilwell, had a high opinion of Chiang Kai-shek, advocated international support for Asian anti - communist movements. Returning to China, he purchased several surplus military aircraft and created the Civil Air Transport, (later known as Air America). These aircraft facilitated aid to Nationalist China during the struggle against Chinese Communists in the late 1940s, and were later used in supply missions to French forces in Indochina and the Kuomintang occupation of Northern Burma throughout the mid and late 1950s, providing support for the Thai police force. This same force supplied the intelligence community and others during the Vietnam conflict.

In 1951, a now retired Major General Chennault testified and provided written statements to the Senate Joint Committee on Armed Forces and Foreign Relations, which was investigating the causes of the fall of China in 1949 to Communist forces. Together with Army General Albert C. Wedemeyer, Navy Vice Admiral Oscar C. Badger II, and others, Chennault stated that the Truman administration's arms embargo was a key factor in the loss of morale to the Nationalist armies.

Chennault advocated changes in the way foreign aid was distributed, encouraged the U.S. Congress to focus on individualized aid assistance with specific goals, with close monitoring by U.S. advisers. This viewpoint may have reflected his experiences during the Chinese Civil War, where officials of the Kuomintang and semi - independent army officers diverted aid intended for the Nationalist armies. Shortly before his death, Chennault was asked to testify before the House Un - American Activities Committee of the Congress. When a committee member asked him who won the Korean War, his response was blunt: "The Communists."

Chennault was promoted to Lieutenant General in the U.S. Air Force, several days before his death on July 27, 1958 at the Ochsner Foundation Hospital in New Orleans. He died of lung cancer. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery (Section 2, 873).

Chennault was twice married and had a total of ten children, eight by his first wife, the former Nell Thompson (1893 – 1977), an American of British ancestry, whom he met at a high school graduation ceremony and subsequently wed in Winnsboro, Louisiana, on December 24, 1911. By the time he was serving in China, they had divorced. He had two children by his second wife, Chen Xiangmei (Anna Chennault), a young reporter for the Central News Agency. She became one of the ROC's chief lobbyists in Washington.

His children from the first marriage were John Stephen Chennault (1913 – 1977), Max Thompson Chennault (1914 – 2001), Charles Lee Chennault (1918 – 1967), Peggy Sue Chennault Lee (born 1919), Claire Patterson Chennault (November 24, 1920 – October 3, 2011), David Wallace Chennault (1923 – 1980), Robert Kenneth Chennault (1925 – 2006), and Rosemary Louise Chennault Simrall (born 1928). By his second wife, he had two daughters, Claire Anna Chennault (born 1948) and Cynthia Louise Chennault (born 1950), a professor of Chinese at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

On January 11, 1960, his son, David Chennault was defeated in a Democratic runoff election for the office of Louisiana state custodian of voting machines. He lost to the incumbent, Douglas Fowler.

Son Claire P. Chennault was a United States Army Air Corps and then Air Force officer from 1943 to 1966 and subsequent resident of Ferriday.

Chennault was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in December 1972, along with Leroy Grumman, Curtis LeMay and James H. Kindelberger. The ceremony was headed by retired Brigadier General Jimmy Stewart, and a portrait of Chennault by cartoonist Milton Caniff was unveiled. General Electric vice president Gerhard Neumann, a former AVG crew chief and the tech sergeant who repaired a downed Zero for flight, spoke of Chennault's unorthodox methods and of his strong personality. An award plaque was presented by Stewart to presidential adviser Thomas Gardiner Corcoran and fighter ace John R. "Johnny" Alison, who both accepted for Anna Chennault, who could not attend.

He was honored by the United States Postal Service with a 40˘ Great Americans series (1980 – 2000) postage stamp.

Chennault is commemorated by a statue in the ROC capital of Taipei, as well as by monuments on the grounds of the Louisiana state capitol at Baton Rouge, and at the former Chennault Air Force Base, now the commercial Chennault International Airport in Lake Charles, Louisiana. A city park and public golf course in Monroe, Louisiana, is also named in his honor. A vintage Curtiss P-40 aircraft, nicknamed "Joy", is on display at the riverside war memorial in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, painted in the colors of the Flying Tigers. In 2006 the University of Louisiana at Monroe renamed its athletic teams Warhawks honoring Chennaults AVG Curtiss P-40 fighter aircraft nickname. A large display of General Chennault's orders, medals and other decorations has been on loan to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum (Washington D.C.) by his widow Anna since the museum's opening in 1976.

In 2005, the "Flying Tigers Memorial" was built in Huaihua, Hunan Province, on one of the old airstrips used by the Flying Tigers in the 1940s. On the 65th anniversary of the Japanese surrender to China, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and PRC officials unveiled a statue of Chennault in Zhijiang County, Hunan, the site of the surrender of Japan.

General Albert Coady Wedemeyer (July 9, 1897 – December 17, 1989) was a United States Army commander who served primarily in Asia during World War II. His most notable command was the China theater in the South - East Asia Theater. During the Cold War, Wedemeyer was a chief supporter of the Berlin Airlift.

Albert C. Wedemeyer was born on July 9, 1897, in Omaha, Nebraska, and was a graduate of Creighton Prep High School. In 1919, he graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point. As a U.S. officer, he was appointed to the German war college Kriegsakademie in Berlin, 1936 - 38. Wedemeyer was included in 1938 German maneuvers, which gave him unique insight into German tactical operations. When he returned to Washington, in 1938, Wedemeyer analyzed Germany's grand strategy and dissected German thinking. Wedemeyer thus became the U.S. military's foremost authority on German tactical operations, whose "most ardent student" was George C. Marshall. Wedemeyer was greatly influenced, and his career aided, by his father - in - law, Lieutenant General Stanley Dunbar Embick, who was at that time Deputy Chief of Staff and Director of the War Plans Division. At the outbreak of World War II, Wedemeyer ranked as lieutenant colonel and was assigned as a Staff Officer to the war plans division of the United States War Department. Notably, in 1941 he was the chief author of the Victory Program, which advocated the defeat of Germany's armies in Europe as the prime war objective for the U.S. This plan was adopted and expanded as the war progressed. Additionally, Wedemeyer helped to plan the Normandy Invasion.

In 1943, Wedemeyer was reassigned to the South - East Asia Theater to be Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander of the South East Asia Command (SEAC), Lord Louis Mountbatten.

On October 27, 1944, General Wedemeyer received a telegram from General George C. Marshall directing him to proceed to China to assume command of U.S. forces in China, replacing General Joseph Stilwell. In his new command, Wedemeyer was also named Chief of Staff to the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. The telegram contained a host of special instructions and limitations on Wedemeyer's command when dealing with the government of Nationalist China. Wedemeyer later recalled his initial dread over the assignment, as service in the China theater was considered a graveyard for American officials, both military and diplomatic. When Wedemeyer actually arrived at Stilwell’s headquarters after Stilwell’s dismissal, he was dismayed to discover that Stilwell had intentionally departed without seeing him, and did not leave a single briefing paper for his guidance, though departing U.S. military commanders habitually greeted their replacement in order to thoroughly brief them on the strengths and weaknesses of headquarters staff, the issues confronting the command, and planned operations. Searching the offices, Wedemeyer could find no documentary record of Stilwell's plans or records of his former or future operations. General Wedemeyer then spoke with Stilwell’s staff officers but learned little from them because Stilwell, according to the staff, kept everything in his “hip pocket”.

During his time in the CBI, Wedemeyer attempted to motivate the Nationalist Chinese government to take a more aggressive role against the Japanese in the war. He was instrumental in expanding the Hump airlift operation with additional, more capable transport aircraft, and continued Stilwell's programs to train, equip and modernize the Nationalist Chinese Army. His efforts were not wholly successful, in part because of the ill will engendered by his predecessor, as well as continuing friction over the role of Communist Chinese forces. Wedemeyer also supervised logistical support for American air forces in China. These forces included the United States Twentieth Air Force partaking in Operation Matterhorn and the Fourteenth Air Force operated by General Claire Chennault.

"There is a nice story about Wedemeyer. A British general took great exception to Wedemeyer's pronunciation of the word 'schedule', which as all Americans do, he pronounced 'skedule'. 'Where did you learn to speak like that?' he asked. Wedemeyer replied: 'I must have learned it at "school"!'"

On December 7, 1945, Wedemeyer with General Douglas MacArthur, and Navy Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the three top military officers in the Far East, recommended to the Pentagon transporting six more Chinese Nationalist armies into North China and Manchuria. However they also suggested that "the U.S. assistance to China, as outlined above, be made available as basis for negotiation by the American Ambassador to bring together and effect a compromise between the major opposing groups in order to promote a united and democratic China."

The issue of forcing the Nationalists into a coalition government with the Communists would later become a central issue in the fierce "Who lost China" political debates in the United States during 1949 - 51. On July 10, 1945, Wedemeyer had informed General Marshall:

If Uncle Sugar, Russia and Britain united strongly in their endeavor to bring about a coalition of these two political parties [the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party] in China by coercing both sides to make realistic concessions, serious post - war disturbance may be averted and timely effective military employment of all Chinese may be obtained against the Japanese. I use the term coercion advisedly because it is my conviction that continued appeals to both sides couched in polite diplomatic terms will not accomplish unification. There must be teeth in Big Three.

Wedemeyer later said as a military commander, his statement was intended as a call to force the long heralded, but never implemented, military alliance between the Nationalist government and Chinese Communists in order to rout undefeated Japanese forces in China, which at the time threatened to continue fighting into 1946. He later told others that he had opposed a political coalition. Wedemeyer served in China into 1946.

After returning from China, Wedemeyer was promoted to Army Chief of Plans and Operations. In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman sent Lieutenant General Wedemeyer to China and Korea to examine the "political, economic, psychological and military situations." The result was the "Wedemeyer Report," in which Wedemeyer stressed the need for intensive U.S. training of and assistance to the Nationalist armies.

Fearful the Nationalists may rise to challenge U.S. hegemony in the Far East, President Truman not only rejected the recommendations in the report, but imposed an arms embargo against the Nationalist government, thereby intensifying the bitter political debate over the role of the United States in the Chinese civil war. While Secretary of State George C. Marshall had hoped that Wedemeyer could convince Chiang Kai-shek to institute those military, economic and political reforms necessary to defeat the Communists, he accepted Truman's views, and suppressed publication of Wedemeyer's report, further provoking resentment by pro - Nationalist and / or anti - communist advocates both inside and outside the U.S. government and the armed forces.

After the fall of China to Communist forces, General Wedemeyer would testify before Congress that while the loss of morale was indeed a cause of the defeat of the Nationalist Chinese forces, the Truman administration's 1947 decision to discontinue further training and modernizing of Nationalist forces, the U.S. - imposed arms embargo, and constant anti - Nationalist sentiment expressed by Western journalists and policymakers were primary causes of that loss of morale. In particular, Wedemeyer stressed that if the U.S. had insisted on experienced American military advisers attached at the lower battalion and regimental levels of Nationalist armies (as it had done with Greek army forces during the Greek Civil War), that aid could have more efficiently been utilized, and that the immediate tactical assistance would have resulted in Nationalist armies performing far better in combat against the Communist Chinese. Vice Admiral Oscar C. Badger, General Claire Chennault and Brigadier General Francis Brink also testified that the arms embargo was a significant factor in the loss of China.

In 1948, Wedemeyer supported General Lucius D. Clay's plan to create an airbridge during the Berlin Crisis.

After the Communist victory in 1949, Wedemeyer became intimately associated with the China Lobby and openly voiced his criticism of those responsible for the "loss of China." In 1951, Wedemeyer retired, but was promoted to General (4 stars) on July 19, 1954.

In 1951, after the outbreak of the Korean War, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy said that Wedemeyer had prepared a wise plan that would keep China a valued ally, but that it had been sabotaged; "only in treason can we find why evil genius thwarted and frustrated it." The evil geniuses, McCarthy said, included General George Marshall. Wedemeyer became a hero to the anti - Communist movement in the United States, giving many lectures around the country.

In 1957 he was affiliated with the National Investigations Committee On Aerial Phenomena.

On May 23, 1985, Wedemeyer was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan.

Friends Advice, in Boyds, Maryland, was his permanent home throughout his military career and after his retirement in 1951, until his death in 1989. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. On December 17, 1989, Wedemeyer died at Fort Belvoir, Virginia.