<Back to Index>

- Général d'Armée Henri Honoré Giraud, 1879

- General of the French Army Paul Legentilhomme, 1884

- General of the French Army Philippe Francois Marie, comte de Hauteclocque (Maréchal Leclerc), 1902

PAGE SPONSOR

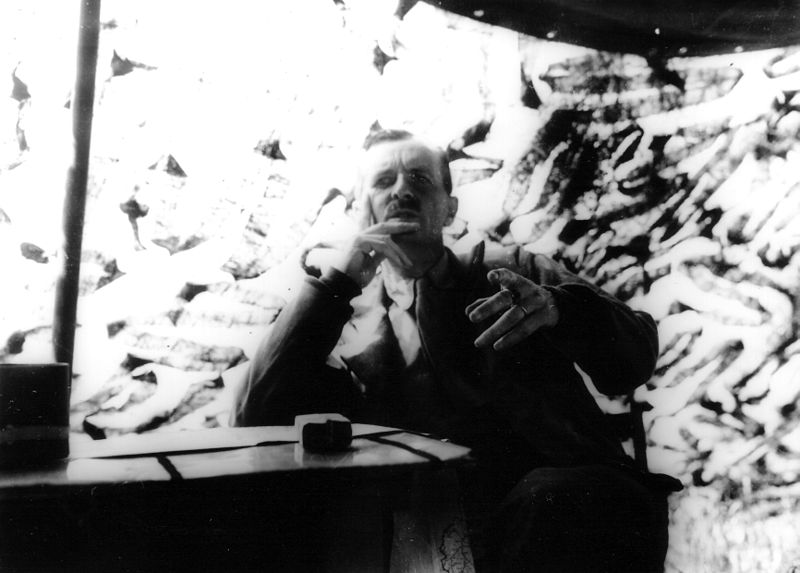

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general who was captured in both World Wars, but escaped both times.

After his second escape in 1942, some of the Vichy ministers tried to send him back to Germany and probable execution. But Eisenhower secretly asked him to take command of French troops in North Africa during Operation Torch and direct them to join the Allies. Only after Darlan's assassination was he able to attain this post, and he took part in the Casablanca Conference with de Gaulle, Churchill and Roosevelt. He decided to retire in 1944 after continual disagreements with de Gaulle.

Henri Giraud was born in Paris, of Alsatian descent. He graduated from the Saint - Cyr Military Academy in 1900 and joined the French Army, serving in North Africa until he was transferred back to France in 1914 when World War I broke out, when he commanded Zouave troops. He was captured in the Battle of Guise in August 1914, when he was seriously wounded, but escaped two months later and returned to France via the Netherlands.

Afterwards, Giraud served with French troops in Constantinople under General Franchet d'Esperey. In 1933, he was transferred to Morocco to fight against Rif (kabyle) rebels. He was awarded the Légion d'Honneur after the capture of Abd-el-Krim and later became the military commander of Metz.

When World War II began, Giraud was a member of the Superior War Council, and disagreed with Charles de Gaulle about the tactics of using armored troops. He became the commander of the 7th Army when it was sent to the Netherlands on 10 May 1940 and was able to delay German troops at Breda on 13 May. Subsequently, the depleted 7th Army was merged with the 9th. While trying to block a German attack through the Ardennes, he was captured by German troops at Wassigny on 19 May. A court martial tried Giraud for ordering the execution of two German saboteurs wearing civilian clothes, but he was acquitted and taken to Königstein Castle near Dresden, which was used as a high security POW prison.

Giraud planned his escape carefully over two years. He learned German and memorized a map of the surrounding area. On 17 April 1942, he lowered himself down the cliff of the mountain fortress. He had shaved off his mustache, and, wearing a Tyrolean hat, traveled to Schandau to meet his SOE contact. Through various ruses, he reached the Swiss border and eventually slipped into Vichy France. After escaping from prison, he told Marshal Pétain that Germany would lose and they must resist. The Vichy government refused to return Giraud to the Germans.

Giraud's escape was soon known all over France. Heinrich Himmler ordered the Gestapo to assassinate him, and Pierre Laval tried to persuade him to return to Germany. Yet he refused to return. Giraud supported Pétain and the Vichy government, but refused to cooperate with the Germans.

He was secretly contacted by the Allies, who gave him the code name Kingpin. Giraud was already planning for the day when American troops landed in France. He agreed to support an Allied landing in French North Africa, provided that only American troops were used, and that he or another French officer was the commander of such an operation. He considered this latter condition essential to maintaining French sovereignty and authority over the Arab and Berber natives of North Africa.

Giraud designated General Charles Mast as his representative in Algeria. At a secret meeting on 23 October with U.S. General Mark W. Clark and diplomat Robert Murphy, the invasion was agreed on, but the Americans promised only that Giraud would be in command "as soon as possible". Giraud, still in France, responded with a demand for a written commitment that he would be commander within 48 hours of the landing, and for landings in France as well as North Africa. Giraud also insisted that he could not leave France before 20 November.

However, Giraud was persuaded that he had to go. On 5 November, he was picked up near Toulon by the British submarine HMS Seraph, which was clumsily disguised as a U.S. vessel to placate Giraud. Eisenhower had advised, contrary to Giraud's request to be fetched by airplane, that he be fetched by the British submarine under an American captain. Seraph took him to meet General Dwight Eisenhower in Gibraltar. He arrived on 7 November, only a few hours before the landings. Eisenhower asked him to assume command of French troops in North Africa during Operation Torch and direct them to join the Allies.

But Giraud had expected to command the whole operation, and adamantly refused to participate on any other basis. He said "his honor would be tarnished" and that he would only be a spectator in the affair.

However, by the next morning, Giraud relented. He refused to leave immediately for Algiers, but rather stayed in Gibraltar until 9 November. When asked why he did not go to Algiers he replied: "You may have seen something of the large de Gaullist demonstration that was held here last Sunday. Some of the demonstrators sang the Marseillaise. I entirely approve of that! Others sang the Chant du Depart [a military ballad]. Quite satisfactory! Others again shouted 'Vive de Gaulle!' No objection. But some of them cried 'Death to Giraud!' I don't approve of that at all."

Pro - Allied elements in Algeria had agreed to support the Allied landings, and in fact seized Algiers on the night of 7–8 November; the city was then occupied by Allied troops. However, resistance continued at Oran and Casablanca. Giraud flew to Algiers on 9 November, but his attempt to assume command of French forces was rebuffed; his broadcast directing French troops to cease resistance and join the Allies was ignored.

Instead, it appeared that Admiral Darlan, who happened to be in Algiers, had real authority. Even Giraud realized this. Despite Darlan's Vichyite reputation, the Allies recognized him as head of French forces, and he ordered the French to cease fire and join the Allies on 10 November.

On 11 November, German forces occupied southern France. Negotiations continued in Algiers; by 13 November, Darlan was recognized as high commissioner of French North and West Africa, while Giraud was appointed commander of all French forces under Darlan.

All this took place without reference to the Free French organization of de Gaulle, which had claimed to be the legitimate government of France in exile.

Then on 24 December, Darlan was assassinated in mysterious circumstances. On the afternoon of 24 December 1942, the admiral drove to his offices at the Palais d'Ete and was shot down at the door to his bureau by a young man of 20, Bonnier de la Chapelle, a monarchist. The young man was tried by court martial under Giraud's orders and executed on the 26th. With the strong backing of the Allies, especially Eisenhower, Giraud was elected to succeed Darlan.

After Admiral Darlan's assassination, Giraud became his de facto successor with Allied support. This occurred through a series of consultations between Giraud and de Gaulle. De Gaulle wanted to pursue a political position in France and agreed to have Giraud as commander - in - chief, as the more militarily qualified of the two. It is probable that he ordered that many French resistance leaders who had helped Eisenhower's troops be arrested, without any protest by Roosevelt's representative, Robert Murphy. Giraud took part in the Casablanca conference, with Roosevelt, Churchill and de Gaulle, in January 1943. Later, after very difficult negotiations, Giraud agreed to suppress the racist laws and to liberate Vichy prisoners from the South Algerian concentration camps. Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle then became co-presidents of the Comité français de la Libération Nationale and Free French Forces. Giraud wanted to lift all racial laws immediately; however, only the Cremieux decree was immediately restored by General de Gaulle. De Gaulle consolidated his political position at Giraud's expense because he was more up to date with the political situation.

Following the Resistance uprising in Corsica on 11 September 1943, Giraud sent an expedition, including two French destroyers, to help the resistance movement without informing the Committee. This drew more criticism from de Gaulle, and he lost the co-presidency in November 1943.

When the Allies found out that Giraud was maintaining his own intelligence network, the French committee forced him from his post as a commander - in - chief of the French forces. He refused to accept a post of Inspector General of the Army and chose to retire. On 28 August 1944, he survived an assassination attempt in Algeria. On 10 March 1944 he received a telegram from Winston Churchill offering Churchill's sympathy for the death of Giraud's daughter who was captured in Tunisia and carried off into Germany with her 4 children.

On 2 June 1946, he was elected to the French Constituent Assembly as a representative of the Republican Party of Liberty and helped to create the constitution of the Fourth Republic. He remained a member of the War Council and was decorated for his escape. He published two books, Mes Evasions (My Escapes, 1946) and Un seul but, la victoire: Alger 1942 - 1944 (A Single Goal, Victory: Algiers 1942 – 1944, 1949) about his experiences.

Henri Giraud died in Dijon, France, on 11 March 1949.

Paul Legentilhomme (Paul Louis Le Gentilhomme) (1884 – 1975) was an officer in the French Army during World War I and World War II. After the fall of France in 1940, he joined the forces of the Free French. Legentilhomme was a recipient of the "Order of the Liberation" (Compagnon de la Libération).

Legentilhomme was born on March 26, 1884 in Valognes, Manche.

- 1905 to 1907 : Cadet at the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr (promotion "la Dernière du vieux Bahut")

- 1907 : Promoted to Sub-Lieutenant

- 1909 : Promoted to Lieutenant

World War I

- 1914 : His unit took part in the battle of Neufchâteau in Belgium, on August 22, and was captured by the Germans.

- 1914 to1918 : In German captivity.

- 1918 : Promoted to Captain

Interwar period

- 1924 : Promoted to Major

- 1926 to 1928 : Chief of Staff Madagascar

- 1929 : Promoted to Lieutenant Colonel

- 1929 to 1931 : Chief of Staff 3rd Colonial Division

- 1934 : Promoted to Colonel

- 1937 to 1938 : Commanding Officer 4th Senegalese Tirailleurs Regiment

- 1938 : Promoted to Brigadier General

World War II

- 1939

-

- 1939 to 1940 : Commander in Chief of the French military units stationed in French Somaliland (present day Djibouti).

- 1940

-

- June 18 : In Djibouti, the capital of French Somaliland, Legentilhomme condemned the French armistice and declared his intention to continue the war with the British Empire. He declared this in his "General Order Number 4".

- August 2 : Left French Somaliland (Vichy French until 1942) and went to the United Kingdom.

- October 31 : Legentilhomme stripped of his French citizenship by the Vichy government.

- 1941

-

- Legentilhomme promoted to Major General in the Free French Army and returned to East Africa as the Commander - in - Chief of the Free French Forces in the Sudan and Eritrea. As part of Brigadier Harold Rawdon Briggs' Briggsforce, Free French forces participated in the East African Campaign. Legentilhomme worked under the supreme command of Field Marshal Archibald Wavell, 1st Earl Wavell.

- Created the First French light division or 1st Free French Division (in French "1ère Division légère française libre" or "1ère DLFL").

- Commanded the 1st Free French Division and Gentforce during Syria - Lebanon Campaign.

- Commander in Chief of Free French forces in Africa.

- November : Legentilhomme condemned in his absence for treason by the Government of Vichy to the death penalty.

- National Commissioner of War

- 1942

-

- Awarded the Compagnon de la Libération cross by the General Charles de Gaulle on 9 September 1942,

- High Commissioner of the French possessions in the Indian Ocean

- Governor General of Madagascar

- general Officer Commander in Chief Madagascar

- 1943

-

- Member of the Council of Défense of the Empire,

- Nominated Lieutenant General

- Nominated Commissaire to the French Committee for National Liberation

- 1944 to 1945

-

- general Officer Commanding 3rd Military Region

- Military Governor of Paris

- 1945 to 1946 : General Officer Commanding Paris Military Region

- 1946 to 1947 : General Officer Commanding 1st Military Region

- 1947 : Promoted Army General

- 1947 : Retired

- 1950 : Military advisor of the Minister for French overseas departments and territories

- 1952 : Technical advisor of the Minister François Mitterrand (who became President of the French Republic between 1981 and 1995)

- 1952 to 1958 : Member of the Assemblée de l'Union française sous l'étiquette (French) (UDSR - political party)

- 23 May 1975 : Paul Legentilhomme died at age 91 in Villefranche - sur - Mer, France. He is buried there.

Philippe François Marie, comte de Hauteclocque, then Leclerc de Hauteclocque (by a 1945 decree that incorporated his French Resistance alias Jacques - Philippe Leclerc to his name; 22 November 1902 – 28 November 1947), was a French general during World War II. He became Marshal of France posthumously, in 1952 and is known in France simply as le maréchal Leclerc.

Philippe François Marie de Hauteclocque was born on 22 November 1902 at Belloy - Saint - Léonard in the department of Somme. He was the fifth of six children of Adrien de Hauteclocque, comte de Hauteclocque (1864 – 1945) and Marie - Thérèse van der Cruisse de Waziers (1870 – 1956). Philippe was named in honor of an ancestor killed by Croats in 1635.

He came from an old line of country nobility; his direct ancestors had served in the Fifth Crusade against Egypt, and again in the Eighth Crusade of Saint Louis against Tunisia in 1270. They had also fought at the Battle of Saint - Omer in 1340 and the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745. The family managed to survive the French Revolution. Three members of the family served in Napoleon's Grande Armée and a fourth, who suffered from weak health, in the supply train. The youngest of these had a son, who became a noted egyptologist; he, in turn, had three sons. The first and third became officers in the French Army; serving during the colonial campaigns before both were killed during World War I. The second son was the general’s father; he also served in World War I, but survived the conflict and inherited the family estate in Belloy - Saint - Léonard.

Philippe attended the École spéciale militaire de Saint - Cyr, the French military academy, graduating in 1924, and entered the French Army; he attained the rank of captain in 1937.

During World War II, he joined the Free French forces after the fall of France in June 1940, and made his way to London. He adopted the Resistance pseudonym "Jacques - Philippe Leclerc". Charles de Gaulle upon meeting him promoted him from Captain to Major (commandant) and ordered him to French Equatorial Africa as governor of French Cameroon from 29 August 1940 to 12 November 1940. He commanded the column which attacked the Axis forces from Chad, and, having marched his troops across West Africa, distinguished himself in Tunisia.

After landing in Normandy on 1 August 1944, his 2nd Armored Division participated in the battle of the Falaise Pocket (12 to 21 August), and went on to liberate Paris. Allied troops were avoiding Paris, moving around it clockwise towards Germany. This was to minimize the danger of the destruction of the historic city if the Germans sought to defend it. Leclerc and de Gaulle had to persuade Eisenhower to send troops help the Parisians, who had risen against the Germans. Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division had been part of Patton's Third Army, and when they entered Paris, many had not been informed of the change of command and told the Parisians that they were part of the Third Army. Historian Jean - Paul Cointet places the uprising and the liberation by Leclerc in the context of the political struggle for leadership in post liberation France, both being aimed at cementing de Gaulle's claim.

In an incident that took place 8 May 1945, at Bad Reichenhall, in Bavaria, Leclerc was involved in the capture and execution of French troops fighting with the Waffen-SS. After entering Germany, Leclerc was presented with a defiant group of 11 - 12 captured SS Charlemagne Division men. The Free French General immediately asked them why they wore a German uniform, to which one of them replied by asking the General why he wore an American one (the Free French wore modified US army uniforms). The group of French Waffen-SS men was later executed without any form of military tribunal procedure. However, it is uncertain who gave the order for their deaths.

At the end of World War II in Europe, he received command of the French Far East Expeditionary Corps (Corps expéditionnaire français en Extrême - Orient, CEFEO), and represented France during the surrender of the Japanese Empire on 2 September 1945; previously, in May 1945, he had been appointed a member of the Légion d'honneur, and the same year legally changed his name to Jacques - Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque, incorporating his French Resistance pseudonym.

As new CEFEO commander, Leclerc set forth in October 1945 in French Indochina, first cracking a Vietminh blockade around Saigon, then driving through the Mekong delta and up into the highlands.

Jean Sainteny flew to Saigon to consult Leclerc, then acting as high commissioner, who approved Sainteny's proposal to negotiate with Vietnam. Admiral d'Argenlieu bluntly denounced Leclerc: "I am amazed - yes, that is the word, amazed - that France's fine expeditionary corps in Indochina is commanded by officers who would rather negotiate than fight".

The negotiations did not work. General Leclerc, returned to Paris from Vietnam, now warned that "anti - communism will be a useless tool unless the problem of nationalism is resolved." But his wisdom was ignored. The French Communists, after breaking with Paul Ramadier, triggered a series of strikes and other disorders that plunged France into civil strife. Leclerc was later replaced by Jean - Étienne Valluy.

Jacques - Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque died in 1947 in an airplane accident near Colomb - Béchar, Algeria, and was awarded the honor of Marshal of France posthumously in 1952.

The Leclerc main battle tank built by GIAT Industries (Groupement Industriel des Armements Terrestres) of France is named after him.

There is a monument to Leclerc in the Petit - Montrouge quarter of the 14th arrondissement in Paris, between Avenue de la Porte d'Orléans and Rue de la Légion Étrangère. The monument is near the Square du Serment - de - Koufra. The "serment de Koufra" is a pledge that Leclerc made on 2 March 1941, the day after taking the Italian fort at Kufra, Libya: he swore that his weapons would not be laid down until the French flag flew over the cathedral of Strasbourg.

Jurez de ne déposer les armes que lorsque nos couleurs, nos belles couleurs, flotteront sur la cathédrale de Strasbourg.

Two streets in Paris are named for Leclerc: Avenue du Général Leclerc in the 14th arrondissement and Rue du Maréchal Leclerc in the 12th arrondissement, between the Bois de Vincennes and the Marne River.