<Back to Index>

- Psychologist Jerome Seymour Bruner, 1915

- Psychologist Ulric Gustav Neisser, 1928

PAGE SPONSOR

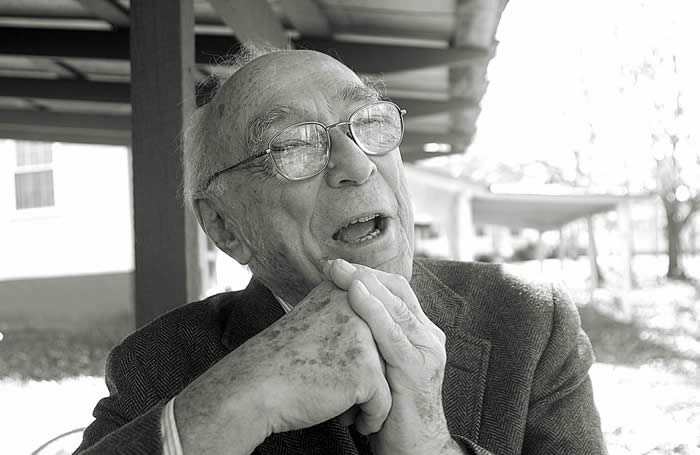

Jerome Seymour Bruner (October 1, 1915 - June 5, 2016) was an American psychologist who made significant contributions to human cognitive psychology and cognitive learning theory in educational psychology, as well as to history and to the general philosophy of education. Bruner was a senior research fellow at the New York University School of Law. He received his B.A. in 1937 from Duke University and his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1941.

Jerome Bruner was born on October 1, 1915 in New York to Polish parents, Heman and Rose Bruner. He received his bachelor's degree in psychology in 1937 from Duke University. Bruner went on to earn a master's degree in psychology in 1939 and then his doctorate in psychology in 1941 from Harvard University. In 1939, Bruner published his first psychological article, studying the effect of thymus extract on the sexual behavior of the female rat. During World War II, Bruner served on the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force Europe committee under Eisenhower, researching social psychological phenomena. Then, in 1945, Bruner returned to Harvard as a psychology professor and was heavily involved in research relating to cognitive psychology and educational psychology. In 1970, Bruner left Harvard to teach at the University of Oxford in England. He returned to the United States in 1980 to continue his research in developmental psychology. In 1991, Bruner joined the faculty at New York University. As an adjunct professor at NYU School of Law, he studid how psychology affects legal practice. Throughout his career, Bruner was awarded honorary doctorates from Yale and Columbia, as well as colleges and universities in such locations as Sorbonne, Berlin and Rome, and was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Bruner was one of the pioneers of the cognitive psychology movement in the United States. This began through his own research when he began to study sensation and perception as being active, rather than passive processes. In 1947, Bruner published his classic study Value and Need as Organizing Factors in Perception in which poor and rich children were asked to estimate the size of coins or wooden disks the size of American pennies, nickels, dimes, quarters and half - dollars. The results showed that the value and need the poor and rich children associated with coins caused them to significantly overestimate the size of the coins, especially when compared to their more accurate estimations of the same size disks. Similarly, another classic study conducted by Bruner and Leo Postman showed slower reaction times and less accurate answers when a deck of playing cards reversed the color of the suit symbol for some cards (e.g., red spades and black hearts). These series of experiments issued in what some called the 'New Look' psychology, which challenged psychologists to study not just an organism's response to a stimulus, but also its internal interpretation. After these experiments on perception, Bruner turned his attention to the actual cognitions that he had indirectly studied in his perception studies. In 1956, Bruner published a book A Study of Thinking which formerly initiated the study of cognitive psychology. Then, in 1956, Bruner helped found the Center of Cognitive Studies at Harvard. After a time, Bruner began to do research on other topics in psychology, but in 1990 he returned to the subject and gave a series of lectures. The lectures were complied into a book Acts of Meaning and in these lectures, Bruner refuted the computer model for studying the mind, advocating a more holistic understanding of the mind and its cognitions.

Beginning around 1967, Bruner turned his attention toward the subject of developmental psychology. Bruner studied how children learned: he coined the term "scaffolding" to describe how children often build off the information they have already mastered.

In his research on the development of children (1966), Bruner proposed three modes of representation: enactive representation (action based), iconic representation (image based), and symbolic representation (language based). Rather than neatly delineated stages, the modes of representation are integrated and only loosely sequential as they "translate" into each other. Symbolic representation remains the ultimate mode, for it "is clearly the most mysterious of the three."

Bruner's theory suggests it is efficacious when faced with new material to follow a progression from enactive to iconic to symbolic representation; this holds true even for adult learners. A true instructional designer, Bruner's work also suggests that a learner (even of a very young age) is capable of learning any material so long as the instruction is organized appropriately, in sharp contrast to the beliefs of Piaget and other stage theorists. Like Bloom's Taxonomy, Bruner suggests a system of coding in which people form a hierarchical arrangement of related categories. Each successively higher level of categories becomes more specific, echoing Benjamin Bloom's understanding of knowledge acquisition as well as the related idea of instructional scaffolding.

In accordance with this understanding of learning, Bruner proposed the spiral curriculum, a teaching approach in which each subject or skill area is revisited at intervals, at a more sophisticated level each time.

While Bruner was at Harvard he published a series of works about his assessment of current educational systems and ways that education could be improved. In 1961, he published the book Process of Education. Bruner also served as a member of the Educational Panel of the President's Science Advisory Committee during the presidencies of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Referencing his overall view that education should not focus merely on the memorization of facts, Bruner wrote in Process of Education that 'knowing how something is put together is worth a thousand facts about it.' From 1964 - 1996, Bruner sought to develop a complete curriculum for the educational system that would meet the needs of students in three main areas which he called Man; A Course of Study. Bruner wanted to create an educational environment that would focus on (1) what was uniquely human about human beings, (2) how humans got that way and (3) how humans could become more so. In 1966, Bruner published another book relevant to education, Towards a Theory of Instruction, and then in 1973, another book, The Relevance of Education was published. Finally, in 1996, Bruner wrote another book, The Culture of Education, reassessing the state of educational practices three decades after he had begun his educational research. Bruner was also credited with helping found the early childcare program Head Start. Since 1995 Professor Jerome Bruner was deeply impressed by his visit to the preschools of Reggio Emilia and has established a collaborative relationship with them to improve educational systems internationally. Equally important was the relationship with the Italian Ministry of Education who officially recognized the value of this innovative experience.

In 1972 Bruner was appointed Watts Professor of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford, where he remained until 1980. In his Oxford years, Bruner focused on early language development. Rejecting the nativist account of language acquisition proposed by Noam Chomsky, Bruner offered an alternative in the form of an interactionist or social interactionist theory of language development. In this approach, the social and interpersonal nature of language was emphasized, appealing to the work of philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, John L. Austin and John Searle for theoretical grounding. Following Lev Vygotsky the Russian theoretician of socio - cultural development, Bruner proposed that social interaction plays a fundamental role in the development of cognition in general and language in particular. He emphasized that children learn language in order to communicate, and, at the same time, they also learn the linguistic code. Meaningful language is acquired in the context of meaningful parent - infant interaction, learning “scaffolded” or supported by the child’s Language Acquisition Support System (LASS).

In Oxford Bruner collected a large group of graduate students and post - doctoral fellows who participated in the effort to understand how young children manage to crack the linguistic code, among them Alison Gopnik, Magda Kalmar, Alan Leslie, Andrew Meltzoff, Anat Ninio, Roy Pea, Susan Sugarman, Michael Scaife, Marian Sigman, Kathy Sylva and many others. Much emphasis was placed in employing the then revolutionary method of videotaped home observations, Bruner showing the way to a new wave of researchers to get out of the laboratory and take on the complexities of naturally occurring events in a child’s life. This work was published in a large number of journal articles, and in 1983 Bruner published a summary of them in the book Child’s talk: Learning to Use Language.

This decade of research firmly established Bruner at the helm of the interactionist approach to language development, exploring such themes as the acquisition of communicative intents and the development of their linguistic expression; the interactive context of language use in early childhood; and the role of parental input and scaffolding behavior in the acquisition of linguistic forms. This work rests on the assumptions of a social constructivist theory of meaning according to which meaningful participation in the social life of a group as well as meaningful use of language involve an interpersonal, intersubjective, collaborative process of creating shared meaning. The elucidation of this process became the focus of Bruner’s next period of work.

In 1980 Bruner returned to the United States, taking up the position of professor at the New School for Social Research in New York City in 1981. For the next decade, he worked on the development of a theory of the narrative construction of reality, his work culminating in several seminal publications. His book Actual Minds, Possible Worlds has been cited by over 16,100 scholarly publications, making it one of the most influential works of the 20th century.

In 1991, Bruner arrived at NYU as a visiting professor to do research and to found the Colloquium on the Theory of Legal Practice. The goal of this institution was to "study how law is practiced and how its practice can be understood by using tools developed in anthropology, psychology, linguistics, and literary theory." Bruner was Senior Research Fellow in Law at NYU.

Ulric Gustav Neisser (December 8, 1928 – February 17, 2012) was a German born, American psychologist and member of the National Academy of Sciences. He was a significant figure in the development of cognitive science and the shift from behaviorist to cognitive models in psychology.

Born in Kiel, Germany, he moved with his family to the United States in 1933. Neisser earned a bachelor's degree summa cum laude from Harvard University in 1950, a Master’s at Swarthmore College, and a doctorate from Harvard's Department of Social Relations in 1956. He then taught at Brandeis and Emory universities, before establishing himself at Cornell.

The modern growth of cognitive psychology received a major boost from the publication in 1967 of the first, and most influential, of his books: Cognitive Psychology.

In 1976, he wrote Cognition and Reality, in which he expressed three general criticisms of the field of cognitive psychology. First, he was dissatisfied with the linear programming model of cognitive psychology, with its overemphasis on peculiar information processing models used to describe and explain behavior. Second, he felt that cognitive psychology had failed to address the everyday aspects and functions of human behavior. He placed blame for this failure largely on the excessive reliance on artificial laboratory tasks that had become endemic to cognitive psychology by the mid 1970s. In this sense, he felt that cognitive psychology suffered a severe disconnect between theories of behavior tested by laboratory experimentation and real world behavior, which he called a lack of ecological validity. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, he had come to feel a great respect for the theory of direct perception and information pickup that had been promulgated by the preeminent perceptual psychologist J.J. Gibson and his wife, the "grand dame" of developmental psychology, Eleanor Gibson. Neisser, in this book, had come to the conclusion that cognitive psychology had little hope of achieving its potential without taking careful theoretical note of the Gibsons' work on perception which argued that understanding human behavior first involves careful analysis of the information available to any perceiving organism.

In 1981, Neisser published John Dean's memory: a case study, in regards to the testimony of John Dean for the Watergate Scandal.

In 1995, he headed an American Psychological Association task force that reviewed The Bell Curve and related controversies in the study of intelligence, in response to the claims being advanced amid the controversy surrounding The Bell Curve. The task force produced a consensus report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns". In April 1996, Neisser chaired a conference at Emory University that focused on secular changes in intelligence test scores.

In 1998, he published The Rising Curve: Long - Term Gains in IQ and Related Measures.

He was a board member of the False Memory Foundation.

During his life, Neisser was both a Guggenheim and Sloan Fellow.

According to William Mace of Trinity College, Neisser died in 2012 from complications of Parkinson's disease.