<Back to Index>

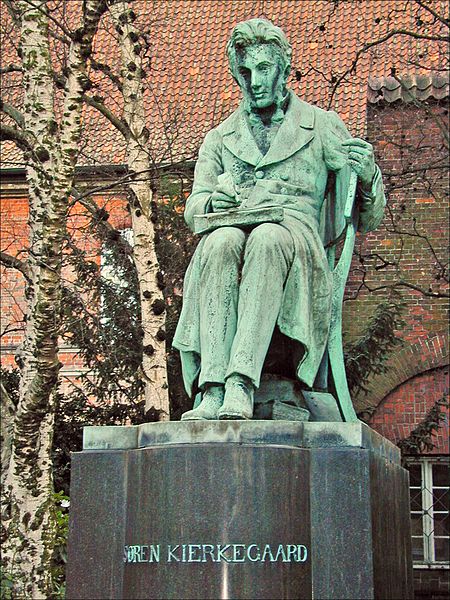

- Philosopher and Writer Søren Aabye Kierkegaard, 1813

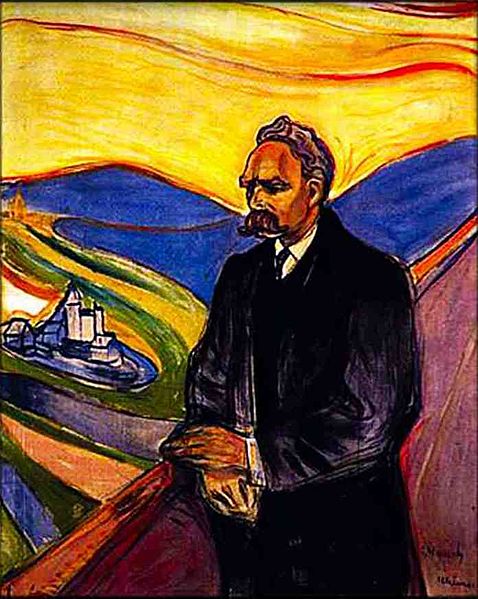

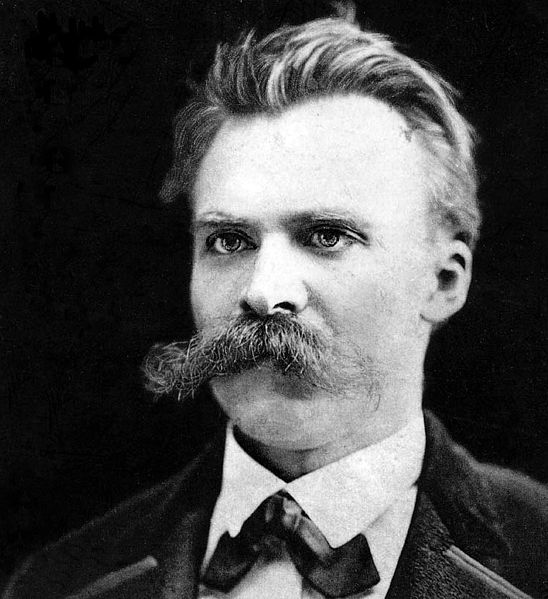

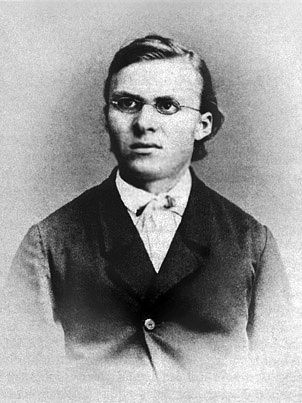

- Philosopher and Writer Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, 1844

PAGE SPONSOR

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, social critic and religious author. He wrote critical texts on organized religion, Christendom, morality, ethics, psychology and philosophy of religion, displaying a fondness for metaphor, irony and parables. He is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher.

Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a "single individual", giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking, and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment. He was a fierce critic of idealist intellectuals and philosophers of his time, such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel.

His theological work focuses on Christian ethics, on the institution of the Church, and on the differences between purely objective proofs of Christianity. He wrote of the individual's subjective relationship to Jesus Christ, the God - Man, which came through faith. Much of his work deals with the art of Christian love. He was also critical of the state and practice of Christianity, primarily that of the Church of Denmark.

Worldly wisdom is of the opinion that love is a relationship between persons; Christianity teaches that love is a relationship between: a person - God - a person, that is, that God is the middle term. To love God is to love oneself truly; to help another person to love God is to love another person; to be helped by another person to love God is to be loved. Works of Love, Hong p. 106 - 107

His psychological work explored the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with life choices. His thinking was influenced by Socrates and the Socratic method.

Kierkegaard's early work was written under various pseudonyms whom he used to present distinctive viewpoints and interact with each other in complex dialogue. He assigned pseudonyms to explore particular viewpoints in depth, which required several books in some instances, while Kierkegaard, openly or under another pseudonym, critiqued that position. He wrote many Upbuilding Discourses under his own name and dedicated them to the "single individual" who might want to discover the meaning of his works. Notably, he wrote:

"Science and scholarship want to teach that becoming objective is the way. Christianity teaches that the way is to become subjective, to become a subject."

The scientist can learn about the world by observation but Kierkegaard emphatically denied that observation could reveal the inner workings of the spiritual world. In 1847 Kierkegaard described his own view of the single individual:

God is not like a human being; it is not important for God to have visible evidence so that he can see if his cause has been victorious or not; he sees in secret just as well. Moreover, it is so far from being the case that you should help God to learn anew that it is rather he who will help you to learn anew, so that you are weaned from the worldly point of view that insists on visible evidence. (...) A decision in the external sphere is what Christianity does not want; (...) rather it wants to test the individual’s faith."

Søren Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen. His mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, had served as a maid in the household before marrying his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard. She was an unassuming figure: quiet, plain, and not formally educated but Henriette Lund, her granddaughter, wrote that she "wielded the scepter with joy and protected [Soren and Peter] like a hen protecting her children". His father was a "very stern man, to all appearances dry and prosaic, but under his 'rustic cloak' demeanor he concealed an active imagination which not even his great age could blunt." He read the philosophy of Christian Wolff. Kierkegaard preferred the comedies of Ludvig Holberg, the writings of Georg Johann Hamann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Plato, especially those referring to Socrates.

Copenhagen in the 1830s and 1840s had crooked streets where carriages rarely went. Kierkegaard loved to walk them. In 1848, Kierkegaard wrote, "I had real Christian satisfaction in the thought that, if there were no other, there was definitely one man in Copenhagen whom every poor person could freely accost and converse with on the street; that, if there were no other, there was one man who, whatever the society he most commonly frequented, did not shun contact with the poor, but greeted every maidservant he was acquainted with, every manservant, every common laborer." Our Lady's Church was at one end of the city, where Bishop Mynster preached the Gospel. At the other end was the Royal Theater where Fru Heiberg performed.

Based on a speculative interpretation of anecdotes in Kierkegaard's unpublished journals, especially a rough draft of a story called "The Great Earthquake", some early Kierkegaard scholars argued that Michael believed he had earned God's wrath and that none of his children would outlive him. He is said to have believed that his personal sins, perhaps indiscretions such as cursing the name of God in his youth or impregnating Ane out of wedlock, necessitated this punishment. Though five of his seven children died before he did, both Kierkegaard and his brother Peter Christian Kierkegaard, outlived him. Peter, who was seven years Kierkegaard's elder, later became bishop in Aalborg.

Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue, Østre Borgerdyd Gymnasium, in 1830 when the school was situated in Klarebodeme, where he studied Latin and history among other subjects. He went on to study theology at the University of Copenhagen. He had little interest in historical works, philosophy dissatisfied him, and he couldn't see "dedicating himself to Speculation". He said, "What I really need to do is to get clear about "what am I to do", not what I must know". He wanted to "lead a completely human life and not merely one of knowledge." Kierkegaard did not want to be a philosopher in the traditional or Hegelian sense and he did not want to preach a Christianity that was an illusion. "But he had learned from his father that one can do what one will, and his father's life had not discredited this theory." He became a "spy for God". In 1848 Kierkegaard wrote:

Supposing that I had been free to use my talents as I pleased (and that it was not the case that another Power was able to compel me every moment when I was not ready to yield to fair means), I might from the first moment have converted my whole productivity into the channel of the interests of the age, it would have been in my power (if such betrayal were not punished by reducing me to naught) to become what the age demands, and so would have been (Goetheo - Hegelian) one more testimony to the proposition that the world is good, that the race is the truth and that this generation is the court of last resort, that the public is the discoverer of the truth and its judge, &c. For by this treason I should have attained extraordinary success in the world. Instead of this I became (under compulsion) a spy.

One of the first physical descriptions of Kierkegaard comes from an attendee, Hans Brøchner, at his brother Peter's wedding party in 1836: "I found [his appearance] almost comical. He was then twenty - three years old; he had something quite irregular in his entire form and had a strange coiffure. His hair rose almost six inches above his forehead into a tousled crest that gave him a strange, bewildered look."

Kierkegaard's mother "was a nice little woman with an even and happy disposition," according to a grandchild's description. She was never mentioned in Kierkegaard's works. Ane died on 31 July 1834, age 66, possibly from typhus. His father died on 8 August 1838, age 82. On 11 August, Kierkegaard wrote:

My father died on Wednesday (the 8th) at 2:00 am. I so deeply desired that he might have lived a few years more, and I regard his death as the last sacrifice of his love for me, because in dying he did not depart from me but he died for me, in order that something, if possible, might still come of me. Most precious of all that I have inherited from him is his memory, his transfigured image, transfigured not by his poetic imagination (for it does not need that), but transfigured by many little single episodes I am now learning about, and this memory I will try to keep most secret from the world. Right now I feel there is only one person (E. Boesen) with whom I can really talk about him. He was a "faithful friend."

Troels Frederik Lund, his nephew, provided biographers with much information regarding Soren Kierkegaard.

People understand me so little that they do not even understand when I complain of being misunderstood.—Søren Kierkegaard , Journals Feb. 1836

Kierkegaard's Journals were first given to his brother - in - law, J.C. Lund and then to his brother, Peter Kierkegaard, but serious work on them began in 1865. H.P Barnum translated 1833 – 1846 but "threw away a significant portion of the originals." This rendered the journals up to 1847 more of a secondary source of information about Kierkegaard than a primary source.

However, according to Samuel Hugo Bergmann, "Kierkegaard's journals are one of the most important sources for an understanding of his philosophy". Kierkegaard wrote over 7,000 pages in his journals on events, musings, thoughts about his works and everyday remarks. The entire collection of Danish journals was edited and published in 13 volumes consisting of 25 separate bindings including indices. The first English edition of the journals was edited by Alexander Dru in 1938. The style is "literary and poetic [in] manner". Kierkegaard saw his journals as his legacy:

I have never confided in anyone. By being an author I have in a sense made the public my confidant. But in respect of my relation to the public I must, once again, make posterity my confidant. The same people who are there to laugh at one cannot very well be made one's confidant.

Kierkegaard's journals were the source of many aphorisms credited to the philosopher. The following passage, from 1 August 1835, is perhaps his most oft quoted aphorism and a key quote for existentialist studies:

What I really need is to get clear about what I must do, not what I must know, except insofar as knowledge must precede every act. What matters is to find a purpose, to see what it really is that God wills that I shall do; the crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die."

Although his journals clarify some aspects of his work and life, Kierkegaard took care not to reveal too much. Abrupt changes in thought, repetitive writing, and unusual turns of phrase are some among the many tactics he used to throw readers off track. Consequently, there are many varying interpretations of his journals. Kierkegaard did not doubt the importance his journals would have in the future. In December 1849, he wrote: "Were I to die now the effect of my life would be exceptional; much of what I have simply jotted down carelessly in the Journals would become of great importance and have a great effect; for then people would have grown reconciled to me and would be able to grant me what was, and is, my right."

An important aspect of Kierkegaard's life, generally considered to have had a major influence on his work, was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen (1822 – 1904). Kierkegaard and Olsen met on 8 May 1837 and were instantly attracted but sometime around 11 August 1838 he had second thoughts. In his journals, Kierkegaard wrote about his love for her:

You, sovereign queen of my heart, Regina, hidden in the deepest secrecy of my breast, in the fullness of my life - idea, there where it is just as far to heaven as to hell — unknown divinity! O, can I really believe the poets when they say that the first time one sees the beloved object he thinks he has seen her long before, that love like all knowledge is recollection, that love in the single individual also has its prophecies, its types, its myths, its Old Testament. Everywhere, in the face of every girl, I see features of your beauty, but I think I would have to possess the beauty of all the girls in the world to extract your beauty, that I would have to sail around the world to find the portion of the world I want and toward which the deepest secret of my self polarically points — and in the next moment you are so close to me, so present, so overwhelmingly filling my spirit that I am transfigured to myself and feel that here it is good to be. You blind god of erotic love! You who see in secret, will you disclose it to me? Will I find what I am seeking here in this world, will I experience the conclusion of all my life's eccentric premises, will I fold you in my arms, or: Do the Orders say: March on? Have you gone on ahead, you, my longing, transfigured do you beckon to me from another world? O, I will throw everything away in order to become light enough to follow you.

On 8 September 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Olsen. He soon felt disillusioned about his prospects. He broke off the engagement on 11 August 1841, though it is generally believed that the two were deeply in love. In his journals, Kierkegaard mentions his belief that his "melancholy" made him unsuitable for marriage, but his precise motive for ending the engagement remains unclear. The following quote from his Journals sheds some light on the motivation.

and this terrible restlessness — as if wanting to convince myself every moment that it would still be possible to return to her — O God, would that I dared to do it. It is so hard; my last hope in life I had placed in her, and I must deprive myself of it. How strange, I had never really thought of getting married, but I never believed that it would turn out this way and leave so deep a wound. I have always ridiculed those who talked about the power of women, and I still do, but a young, beautiful, soulful girl who loves with all her mind and all her heart, who is completely devoted, who pleads — how often I have been close to setting her love on fire, not to a sinful love, but I need merely have said to her that I loved her, and everything would have been set in motion to end my young life. But then it occurred to me that this would not be good for her, that I might bring a storm upon her head, since she would feel responsible for my death. I prefer what I did do; my relationship to her was always kept so ambiguous that I had it in my power to give it any interpretation I wanted to. I gave it the interpretation that I was a deceiver. Humanly speaking, that is the only way to save her, to give her soul resilience. My sin is that I did not have faith, faith that for God all things are possible, but where is the borderline between that and tempting God; but my sin has never been that I did not love her. If she had not been so devoted to me, so trusting, had not stopped living for herself in order to live for me — well, then the whole thing would have been a trifle; it does not bother me to make a fool of the whole world, but to deceive a young girl. — O, if I dared return to her, and even if she did not believe that I was false, she certainly believed that once I was free I would never come back. Be still, my soul, I will act firmly and decisively according to what I think is right. I will also watch what I write in my letters. I know my moods. But in a letter I cannot, as when I am speaking, instantly dispel an impression when I detect that it is too strong."

Kierkegaard turned attention to his examinations. On 13 May 1839 he wrote, "I have no alternative than to suppose that it is God's will that I prepare for my examination and that it is more pleasing to him that I do this than actually coming to some clearer perception by immersing myself in one or another sort of research, for obedience is more precious to him than the fat of rams." The death of his father and the death of Poul Møller also played a part in his decision.

On 29 September 1841, Kierkegaard wrote and defended his dissertation, On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates. The university panel considered it noteworthy and thoughtful, but too informal and witty for a serious academic thesis. The thesis dealt with irony and Schelling's 1841 lectures, which Kierkegaard had attended with Mikhail Bakunin, Jacob Burckhardt and Friedrich Engels; each had come away with a different perspective. Kierkegaard graduated from university on 20 October 1841 with a Magister Artium, which today would be designated a Ph.D. He was able to fund his education, his living, and several publications of his early works with his family's inheritance of approximately 31,000 rigsdaler.

Kierkegaard published some of his works using pseudonyms and for others he signed his own name as author. On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates was his university thesis, mentioned above. His first book, De omnibus dubitandum est (Latin: "Everything must be doubted"), was written in 1841 – 42 but was not published until after his death. It was written under the pseudonym "Johannes Climacus".

Either / Or was published 20 February 1843; it was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin, where he took notes on Schelling's Philosophy of Revelation. Edited by Victor Eremita, the book contained the papers of an unknown "A" and "B". Kierkegaard writes in Either / Or, "one author seems to be enclosed in another, like the parts in a Chinese puzzle box,"; the puzzle box would prove to be complicated. Kierkegaard claimed to have found these papers in a secret drawer of his secretary.

In Either / Or, he stated that arranging the papers of "B" was easy because "B" was talking about ethical situations, whereas arranging the papers of "A" was more difficult because he was talking about chance, so he left the arranging of those papers to chance. Both the ethicist and the aesthetic writers were discussing outer goods, but Kierkegaard was more interested in inner goods.

Three months after the publication of Either / Or, he published Two Upbuilding Discourses, in which he wrote:

"There is talk of the good things of the world, of health, happy times, prosperity, power, good fortune, a glorious fame. And we are warned against them; the person who has them is warned not to rely on them, and the person who does not have them is warned not to set his heart on them. About faith there is a different kind of talk. It is said to be the highest good, the most beautiful; the most precious, the most blessed riches of all, not to be compared with anything else, incapable of being replaced. Is it distinguished from the other good things, then, by being the highest but otherwise of the same kind as they are — transient and capricious, bestowed only upon the chosen few, rarely for the whole of life? If this were so, then it certainly would be inexplicable that in these sacred places it is always faith and faith alone that is spoken of, that it is eulogized and celebrated again and again."

Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 was published under his own name, rather than a pseudonym. On 16 October 1843 Kierkegaard published three books: Fear and Trembling, under the pseudonym Johannes de Silentio; Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 under his own name; and Repetition as Constantin Constantius. He later published Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843, again using his own name.

In 1844, he published Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1844, and Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 under his own name, Philosophical Fragments under the pseudonym Johannes Climacus, The Concept of Anxiety under two pseudonyms Vigilius Haufniensis, with a Preface, by Nicolaus Notabene, and finally Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 under his own name.

Kierkegaard published Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions under his own name on 29 April, and Stages on Life's Way edited by Hilarius Bookbinder, 30 April 1845. Kierkegaard went to Berlin for a short rest. Upon returning he published his Discourses of 1843 – 44 in one volume, Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, 29 May 1845.

Pseudonyms were used often in the early 19th century as a means of representing viewpoints other than the author's own; examples include the writers of the Federalist Papers and the Anti - Federalist Papers. Kierkegaard employed the same technique.

This was part of Kierkegaard's theory of "indirect communication." He wrote:

No anonymous author can more slyly hide himself, and no maieutic can more carefully recede from a direct relation than God can. He is in the creation, everywhere in the creation, but he is not there directly, and only when the single individual turns inward into himself (consequently only in the inwardness of self - activity) does he become aware and capable of seeing God."

According to several passages in his works and journals, such as The Point of View of My Work as an Author, Kierkegaard used pseudonyms in order to prevent his works from being treated as a philosophical system with a systematic structure. In the Point of View, Kierkegaard wrote:

"The movement: from the poet (from aesthetics), from philosophy (from speculation), to the indication of the most central definition of what Christianity is — from the pseudonymous ‘Either / Or’, through ‘The Concluding Postscript’ with my name as editor, to the ‘Discourses at Communion on Fridays’, two of which were delivered in the Church of our Lady. This movement was accomplished or described uno tenore, in one breath, if I may use this expression, so that the authorship integrally regarded, is religious from first to last — a thing which everyone can see if he is willing to see, and therefore ought to see."

Later he would write:

"... As is well - known, my authorship has two parts: one pseudonymous and the other signed. The pseudonymous writers are poetic creations, poetically maintained so that everything they say is in character with their poetized individualized personalities; sometimes I have carefully explained in a signed preface my own interpretation of what the pseudonym said. Anyone with just a fragment of common sense will perceive that it would be ludicrously confusing to attribute to me everything the poetized characters say. Nevertheless, to be on the safe side, I have expressly urged that anyone who quotes something from the pseudonyms will not attribute the quotation to me (see my postscript to Concluding Postscript). It is easy to see that anyone wanting to have a literary lark merely needs to take some verbatim quotations from "The Seducer," then from Johannes Climacus, then from me, etc., print them together as if they were all my words, show how they contradict each other, and create a very chaotic impression, as if the author were a kind of lunatic. Hurrah! That can be done. In my opinion anyone who exploits the poetic in me by quoting the writings in a confusing way is more or less a charlatan or a literary toper."

Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno and Thomas Henry Croxall argue that the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views. This view leads to confusions and contradictions which make Kierkegaard appear philosophically incoherent. Many later scholars, such as the post - structuralists, interpreted Kierkegaard's work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors. Postmodern Christians present a different interpretation of Kierkegaard's works. Kierkegaard used the category of "The Individual" to stop the endless Either / Or.

Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms, in chronological order, were:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either / Or

- A, writer of many articles in Either / Or

- Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either / Or

- Johannes de silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Constantin Constantius, author of the first half of Repetition

- Young Man, author of the second half of Repetition

- Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Anxiety

- Nicolaus Notabene, author of Prefaces

- Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

- Inter et Inter, author of The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress

- H.H., author of Two Ethical - Religious Essays

- Anti - Climacus, author of The Sickness Unto Death and Practice in Christianity

Kierkegaard wrote two small pieces in response to Møller, The Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action. The former focused on insulting Møller's integrity while the latter was a directed assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard, after criticizing the journalistic quality and reputation of the paper, openly asked The Corsair to satirize him.

Kierkegaard's response earned him the ire of the paper and its second editor, also an intellectual of Kierkegaard's own age, Meïr Aron Goldschmidt. Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his offer to "be abused", and unleashed a series of attacks making fun of Kierkegaard's appearance, voice and habits. For months, Kierkegaard perceived himself to be the victim of harassment on the streets of Denmark. In a journal entry dated 9 March 1846, Kierkegaard made a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explained that this attack made him rethink his strategy of indirect communication.

On 27 February 1846 Kierkegaard published Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, under his first pseudonym, Johannes Climacus. On 30 March 1846 he published Two Ages: A Literary Review, under his own name. A critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg - Ehrensvärd, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on what he considered the nature of modernity and its passionless attitude towards life. Kierkegaard writes that "the present age is essentially a sensible age, devoid of passion [...] The trend today is in the direction of mathematical equality, so that in all classes about so and so many uniformly make one individual". In this, Kierkegaard attacked the conformity and assimilation of individuals into "the crowd" which became the standard for truth, since it was the numerical.

As part of his analysis of the "crowd", Kierkegaard accused newspapers of decay and decadence. Kierkegaard stated Christendom had "lost its way" by recognizing "the crowd," as the many who are moved by newspaper stories, as the court of last resort in relation to "the truth." Truth comes to a single individual, not all people at one and the same time. Just as truth comes to one individual at a time so does love. One doesn't love the crowd but does love their neighbor, who is a single individual. He says, "never have I read in the Holy Scriptures this command: You shall love the crowd; even less: You shall, ethico - religiously, recognize in the crowd the court of last resort in relation to 'the truth.'" Kierkegaard takes out his wrath on the crowd, the public, and especially the newspapers in this short sample of his work. In this quote he also gives an inkling of what true Christianity is like. God must be the middle term.

"The crowd is untruth. And I could weep, in every case I can learn to long for the eternal, whenever I think about our age's misery, even compared with the ancient world's greatest misery, in that the daily press and anonymity make our age even more insane with help from "the public," which is really an abstraction, which makes a claim to be the court of last resort in relation to "the truth"; for assemblies which make this claim surely do not take place. That an anonymous person, with help from the press, day in and day out can speak however he pleases (even with respect to the intellectual, the ethical, the religious), things which he perhaps did not in the least have the courage to say personally in a particular situation; every time he opens up his gullet — one cannot call it a mouth — he can all at once address himself to thousands upon thousands; he can get ten thousand times ten thousand to repeat after him — and no one has to answer for it; in ancient times the relatively unrepentant crowd was the almighty, but now there is the absolutely unrepentant thing: No One, an anonymous person: the Author, an anonymous person: the Public, sometimes even anonymous subscribers, therefore: No One. No One! God in heaven, such states even call themselves Christian states. One cannot say that, again with the help of the press, "the truth" can overcome the lie and the error."O, you who say this, ask yourself: Do you dare to claim that human beings, in a crowd, are just as quick to reach for truth, which is not always palatable, as for untruth, which is always deliciously prepared, when in addition this must be combined with an admission that one has let oneself be deceived! Or do you dare to claim that "the truth" is just as quick to let itself be understood as is untruth, which requires no previous knowledge, no schooling, no discipline, no abstinence, no self - denial, no honest self - concern, no patient labor! No, "the truth," which detests this untruth, the only goal of which is to desire its increase, is not so quick on its feet. Firstly, it cannot work through the fantastical, which is the untruth; its communicator is only a single individual. And its communication relates itself once again to the single individual; for in this view of life the single individual is precisely the truth. The truth can neither be communicated nor be received without being as it were before the eyes of God, nor without God's help, nor without God being involved as the middle term, since he is the truth. It can therefore only be communicated by and received by "the single individual," which, for that matter, every single human being who lives could be: this is the determination of the truth in contrast to the abstract, the fantastical, impersonal, "the crowd" – "the public," which excludes God as the middle term (for the personal God cannot be the middle term in an impersonal relation), and also thereby the truth, for God is the truth and its middle term." Søren Kierkegaard, Copenhagen, Spring 1847

Kierkegaard began to write again in 1847. His first work in this period was Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits, which included Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, and Works of Love, both authored under his own name. There had been much discussion in Denmark about the pseudonymous authors until the publication of Concluding Unscientific Discourses where he openly admitted to be the author of the books because people began wondering if he was, in fact, a Christian or not.

In 1848 he published Christian Discourses under his own name and The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress under the pseudonym Inter et Inter. Kierkegaard also developed The Point of View of My Work as an Author, his autobiographical explanation for his prolific use of pseudonyms. The book was finished in 1848, but not published until after his death.

The Second edition of Either / Or and The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air were both published early in 1849. Later that year he published The Sickness Unto Death, under the pseudonym Anti - Climacus; four months later he wrote Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays under his own name. Another work by Anti - Climacus, Practice in Christianity, was published in 1850, but edited by Kierkegaard. This work was called Training in Christianity when Walter Lowrie translated it in 1941.

In 1851, Kierkegaard began openly presenting his case for Christianity to the "Single Individual". In Practice In Christianity, his last pseudonymous work, he stated, "In this book, originating in the year 1848, the requirement for being a Christian is forced up by the pseudonymous authors to a supreme ideality." He now pointedly referred to the single individual in his next three publications; For Self - Examination, Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays, and in 1852 Judge for Yourselves!. In 1843 he had written in Either / Or:

"I ask: What am I supposed to do if I do not want to be a philosopher, I am well aware that I like other philosophers will have to mediate the past. For one thing, this is no answer to my question 'What am I supposed to do?' for even if I had the most brilliant philosophical mind there ever was, there must be something more I have to do besides sitting and contemplating the past. Second, I am a married man and far from being a philosophical brain, but in all respect I turn to the devotees of this science to find out what I am supposed to do. But I receive no answer, for philosophy mediates the past and is in the past - philosophy hastens so fast into the past that, as a poet says of and antiquarian, only his coattails remain in the present. See, here you are at one with the philosophers. What unites you is that life comes to a halt. For the philosopher, world history is ended, and he mediates. This accounts for the repugnant spectacle that belongs to the order of the day in our age - to see young people who are able to mediate Christianity and paganism, who are able to play games with the titanic forces of history, and who are unable to tell a simple human being what he has to do here in life, nor do they know what they themselves have to do."

A journal entry about Practice in Christianity from 1851 clarified his intention:

What I have understood as the task of the authorship has been done. It is one idea, this continuity from Either / Or to Anti - Climacus, the idea of religiousness in reflection. The task has occupied me totally, for it has occupied me religiously; I have understood the completion of this authorship as my duty, as a responsibility resting upon me. Whether anyone has wanted to buy or to read has concerned me very little. At times I have considered laying down my pen and, if anything should be done, to use my voice. Meanwhile I came by way of further reflection to the realization that it perhaps is more appropriate for me to make at least an attempt once again to use my pen but in a different way, as I would use my voice, consequently in direct address to my contemporaries, winning men, if possible. The first condition for winning men is that the communication reaches them. Therefore I must naturally want this little book to come to the knowledge of as many as possible. If anyone out of interest for the cause — I repeat, out of interest for the cause — wants to work for its dissemination, this is fine with me. It would be still better if he would contribute to its well comprehended dissemination. I hardly need say that by wanting to win men it is not my intention to form a party, to create secular, sensate togetherness; no, my wish is only to win men, if possible all men (each individual), for Christianity. A request, an urgent request to the reader: I beg you to read aloud, if possible; I will thank everyone who does so; and I will thank again and again everyone who in addition to doing it himself influences others to do it." Journals of Søren Kierkegaard, June 1, 1851

I ask: what does it mean when we continue to behave as though all were as it should be, calling ourselves Christians according to the New Testament, when the ideals of the New Testament have gone out of life? The tremendous disproportion which this state of affairs represents has, moreover, been perceived by many. They like to give it this turn: the human race has outgrown Christianity.—Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, p. 446 (19 June 1852)

Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Church of Denmark by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self - published pamphlets called The Moment (Øjeblikket), also translated as "The Instant". These pamphlets are now included in Kierkegaard's Attack Upon Christendom. The Instant, was translated into German as well as other European languages in 1861 and again in 1896.

Kierkegaard first moved to action after Professor (soon bishop) Hans Lassen Martensen gave a speech in church in which he called the recently deceased Bishop Jakob P. Mynster a "truth - witness, one of the authentic truth - witnesses." Kierkegaard explained, in his first article, that Mynster's death permitted him — at last — to be frank about his opinions. He later wrote that all his former output had been "preparations" for this attack, postponed for years waiting for two preconditions: 1) both his father and bishop Mynster should be dead before the attack and 2) he should himself have acquired a name as a famous theologic writer. Kierkegaard's father had been Mynster's close friend, but Søren had long come to see that Mynster's conception of Christianity was mistaken, demanding too little of its adherents. Kierkegaard strongly objected to the portrayal of Mynster as a 'truth - witness'.

During the ten issues of Øjeblikket the aggressiveness of Kierkegaard's language increased; the “thousand Danish priests“ “playing Christianity“ were eventually called “man - eaters“ after having been “liars“, “hypocrites“ and “destroyers of Christianity" in the first issues. This verbal violence caused a sensation in Denmark, but today Kierkegaard is often considered to have lost control of himself during this campaign.

Before the tenth issue of his periodical The Moment could be published, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street. He stayed in the hospital for over a month and refused communion. At that time he regarded pastors as mere political officials, a niche in society who was clearly not representative of the divine. He said to Emil Boesen, a friend since childhood who kept a record of his conversations with Kierkegaard, that his life had been one of immense suffering, which may have seemed like vanity to others, but he did not think it so.

Kierkegaard died in Frederik's Hospital after over a month, possibly from complications from a fall he had taken from a tree in his youth. He was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen. At Kierkegaard's funeral, his nephew Henrik Lund caused a disturbance by protesting Kierkegaard's burial by the official church. Lund maintained that Kierkegaard would never have approved, had he been alive, as he had broken from and denounced the institution. Lund was later fined for his disruption of a funeral.

In Kierkegaard's pamphlets and polemical books, including The Moment, he criticized several aspects of church formalities and politics. According to Kierkegaard, the idea of congregations keeps individuals as children since Christians are disinclined from taking the initiative to take responsibility for their own relation to God. He stressed that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual." Furthermore, since the Church was controlled by the State, Kierkegaard believed the State's bureaucratic mission was to increase membership and oversee the welfare of its members. More members would mean more power for the clergymen: a corrupt ideal. This mission would seem at odds with Christianity's true doctrine, which, to Kierkegaard, is to stress the importance of the individual, not the whole. Thus, the state - church political structure is offensive and detrimental to individuals, since anyone can become "Christian" without knowing what it means to be Christian. It is also detrimental to the religion itself since it reduces Christianity to a mere fashionable tradition adhered to by unbelieving "believers", a "herd mentality" of the population, so to speak. In the Journals, Kierkegaard writes:

Søren Kierkegaard has been interpreted and reinterpreted since he published his first book. Some authors change with the times as their productivity progresses and sometimes interpretations of an author change with each new generation. The interpretation of Søren Kierkegaard is still evolving."If the Church is "free" from the state, it's all good. I can immediately fit in this situation. But if the Church is to be emancipated, then I must ask: By what means, in what way? A religious movement must be served religiously — otherwise it is a sham! Consequently, the emancipation must come about through martyrdom — bloody or bloodless. The price of purchase is the spiritual attitude. But those who wish to emancipate the Church by secular and worldly means (i.e., no martyrdom), they've introduced a conception of tolerance entirely consonant with that of the entire world, where tolerance equals indifference, and that is the most terrible offense against Christianity. [...] the doctrine of the established Church, its organization, are both very good indeed. Oh, but then our lives: believe me, they are indeed wretched."

In September 1850, the Western Literary Messenger wrote:

"While Martensen with his wealth of genius casts from his central position light upon every sphere of existence, upon all the phenomena of life, Søren Kierkegaard stands like another Simon Stylites, upon his solitary column, with his eye unchangeably fixed upon one point. Upon this he places his microscope and examines its minutest atoms; scrutinizes its most fleeting movements; its innermost changes, upon this he lectures, upon this he writes again and again, infinite volumes. Everything exists for him in this one point. But this point is - the human heart: and as he ever reflects this changing heart in the eternal unchangeable, in ‘that’ “which became flesh and dwelt among us,” and as he amidst his wearisome logical wanderings often says divine things, he has found in the gay, lively Copenhagen not a small public, and that principally of the ladies. The philosophy of the heart must be near to them."

In 1855, the Danish National Church published his obituary. Kierkegaard did have an impact there judging from the following quote from their article:

"The fatal fruits which Dr. Kierkegaard show to arise from the union of Church and State, have strengthened the scruples of many of the believing laity, who now feel that they can remain no longer in the Church, because thereby they are in communion with unbelievers, for there is no ecclesiastical discipline. Thus, the desire of leaving the Church becomes increasingly strengthened among them. They wish to see J. Lursen (the reader) ordained. One of his friends has lately declared in their journal, that pious laymen are more fit to ordain ministers than the unbelieving priests. An independent Lutheran Church was formed at Copenhagen last December."

Changes did occur in the administration of the Church and these changes were linked to Kierkegaard's writings. The Church noted that dissent was “something foreign to the national mind.” On 5 April 1855 the Church enacted new policies: “every member of a congregation is free to attend the ministry of any clergyman, and is not, as formerly, bound to the one whose parishioner he is”. In March 1857, compulsory infant baptism was abolished. Debates sprang up over the King's position as the head of the Church and over whether to adopt a constitution. Gruntvig objected to having any written rules. Immediately following this announcement the “agitation occasioned by Kierkegaard" was mentioned. Kierkegaard was accused of Weigelianism and Darbyism, but the article continued to say, “One great truth has been made prominent, viz (namely): That there exists a worldly - minded clergy; that many things in the Church are rotten; that all need daily repentance; that one must never be contented with the existing state of either the Church or her pastors. But there is no truth in the assertion that Christianity does not aim at the formation of the Church, or Christianizing the world; that the Church is a mere Babel: that where there is no suffering for Christ’s sake, the Gospel of the New Testament is at an end.”

Hans Martensen wrote a monograph about Kierkegaard in 1856, a year after his death. (untranslated) and mentioned him extensively in Christian Ethics, published in 1871. "Kierkegaard's assertion is therefore perfectly justifiable, that with the category of "the individual" the cause of Christianity must stand and fall; that, without this category, Pantheism had conquered unconditionally. From this, at a glance, it may be seen that Kierkegaard ought to have made common cause with those philosophic and theological writers who specially desired to promote the principle of Personality as opposed to Pantheism. This is, however, far from the case. For those views which upheld the category of existence and personality, in opposition to this abstract idealism, did not do this in the sense of an either - or, but in that of a both - and. They strove to establish the unity of existence and idea, which may be specially seen from the fact that they desired system and totality. Martensen accused Kierkegaard and Alexandre Vinet of not giving society its due. He said both of them put the individual above society, and in so doing, above the Church.

Another early critic was Magnús Eiríksson who criticized Martensen and wanted Kierkegaard as his ally in his fight against speculative theology.

Otto Pfleiderer in The Philosophy of Religion: On the Basis of Its History (1887), claimed that Kierkegaard presented an anti - rational view of Christianity. He went on to assert that the ethical side of a human being has to disappear completely in his one - sided view of faith as the highest good. He wrote, "Kierkegaard can only find true Christianity in entire renunciation of the world, in the following of Christ in lowliness and suffering especially when met by hatred and persecution on the part of the world. Hence his passionate polemic against ecclesiastical Christianity, which he says has fallen away from Christ by coming to a peaceful understanding with the world and conforming itself to the world’s life. True Christianity, on the contrary, is constant polemical pathos, a battle against reason, nature and the world; its commandment is enmity with the world; its way of life is the death of the naturally human.

An article from an 1889 dictionary of religion revealed a good idea of how Kierkegaard was regarded at that time.

“Having never left his native city more than a few days at a time, excepting once, when he went to Germany to study Schelling's philosophy. He was the most original thinker and theological philosopher the North ever produced. His fame has been steadily growing since his death, and he bids fair to become the leading religio - philosophical light of Germany, not only his theological, but also his aesthetic works have of late become the subject of universal study in Europe. (...) Søren Kierkegaard’s writings abound in psychological observations and experiences, great penetration and dexterous experimentations, all of which enable him to speak of that which but few know and fewer still can express, his diction is noble, his dialectics refined and brilliant; scarcely a page of his can be found which is not rich in poetic sentiment and passionate though pure enthusiasm. It is generally conceded that his literary productions overflow with intellectual wonders, still it must be said that he is often more fascinating and seductive than convincing. He defined his task to be 'to call attention to Christianity', to make himself an instrument to summon people to the truly Human. Ideal or true Christianity, so little known, as he claimed, and to which he wanted to call attention, is neither a theory, scientific or otherwise, but a life and a mode of existence; a life which nature can neither define nor teach. It is an existence rooted wholly in the beyond, though it must be realized in actual life. Christian truth is not and cannot be the subject of science, for it is not objective, but purely subjective. He does not deny the value of objective science; he admits its use and necessity in a real world, but he utterly discards any claims it may lay to the spiritual relations of the Christian — relations which are and can be only subjective, personal, and individual. Defined, his perception is this, "Subjectivity is the truth" — a doubtful proposition, and only true with regard to the One who could say about himself, "I am the truth." Rightly understood, it is the speculative principle of Protestantism; but wrongly conceived, it leads to a denial of the church idea. The main element of this philosophy would not have met with any determined opposition had Kierkegaard moderated his language. As it was he defiantly declared war against all speculation as a source of Christianity, and opposed those who seek to speculate on faith — as was the case in his day and before — thereby striving to get an insight into the truths of revelation. Speculation, he claimed, leads to a fall, and to a falsification of the truth."

The dramatist Henrik Ibsen became interested in Kierkegaard and introduced his work to the rest of Scandinavia.

The first academic to draw attention to Kierkegaard was fellow Dane Georg Brandes, who published in German as well as Danish. Brandes gave the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard in Copenhagen and helped bring him to the attention of the European intellectual community. Brandes published the first book on Kierkegaard's philosophy and life. Sören Kierkegaard, ein literarisches Charakterbild. Autorisirte deutsche Ausg (1879) and compared him to Hegel in Reminiscences of my Childhood and Youth (1906). (He also introduced Friedrich Nietzsche to Europe in 1914 by writing a biography about him.) Brandes opposed Kierkegaard's ideas. He wrote elegantly about Christian doubt.

"But my doubt would not be overcome. Kierkegaard had declared that it was only to the consciousness of sin that Christianity was not horror or madness. For me it was sometimes both. I concluded there from that I had no consciousness of sin, and found this idea confirmed when I looked into my own heart. For however violently at this period I reproached myself and condemned my failings, they were always in my eyes weaknesses that ought to be combatted, or defects that could be remedied, never sins that necessitated forgiveness, and for the obtaining of this forgiveness, a Savior. That God had died for me as my Savior, — I could not understand what it meant; it was an idea that conveyed nothing to me. And I wondered whether the inhabitants of another planet would be able to understand how on the Earth that which was contrary to all reason was considered the highest truth."

On 11 January 1888 Brandes wrote the following to Nietzsche, “There is a Northern writer whose works would interest you, if they were but translated, Soren Kierkegaard. He lived from 1813 to 1855, and is in my opinion one of the profoundest psychologists to be met with anywhere. A little book which I have written about him (the translation published at Leipzig in 1879) gives me exhaustive idea of his genius, for the book is a kind of polemical tract written with the purpose of checking his influence. It is, nevertheless, from a psychological point of view, the finest work I have published.” (p. 325) Nietzsche wrote back that he would “tackle Kierkegaard’s psychological problems” and then Brandes asked if he could get a copy of everything Nietzsche had published. (p. 343) so he could spread his “propaganda.” (p. 348, 360 - 361)

He also mentioned him extensively in volume 2 of his 6 volume work, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature.

"In Danish Romanticism there is none of Friedrich Schlegel's audacious immorality, but neither is there anything like that spirit of opposition which in him amounts to genius; his ardor melts, and his daring molds into new and strange shapes, much that we accept as inalterable. Nor do the Danes become Catholic mystics. Protestant orthodoxy in its most petrified form flourishes with us: so do supernaturalism and pietism; and in Grundtvigianism we slide down the inclined plane which leads to Catholicism; but in this matter, as in every other, we never take the final step; we shrink back from the last consequences. The result is that the Danish reaction is far more insidious and covert than the German. Veiling itself as vice does, it clings to the altars of the Church, which have always been a sanctuary for criminals of every species. It is never possible to lay hold of it, to convince it then and there that its principles logically lead to intolerance, inquisition, and despotism. Kierkegaard, for example, is in religion orthodox, in politics a believer in absolutism, towards the close of his career a fanatic. Yet — and this is a genuinely Romantic trait — he all his life long avoids drawing any practical conclusions from his doctrines; one only catches an occasional glimpse of such a feeling as admiration for the Inquisition, or hatred of natural science.

During the 1890s, Japanese philosophers began disseminating the works of Kierkegaard, from the Danish thinkers. Tetsuro Watsuji was one of the first philosophers outside of Scandinavia to write an introduction on his philosophy, in 1915.

Harald Høffding wrote an article about him in A brief history of modern philosophy (1900). Høffding mentioned Kierkegaard in Philosophy of Religion 1906, and the American Journal of Theology (1908) printed an article about Hoffding's Philosophy of Religion. Then Høffding repented of his previous convictions in The problems of philosophy (1913). Høffding was also a friend of the American philosopher William James, and although James had not read Kierkegaard's works, as they were not yet translated into English, he attended the lectures about Kierkegaard by Høffding and agreed with much of those lectures. James' favorite quote from Kierkegaard came from Høffding: "We live forwards but we understand backwards". This was, however, a misquote, in that Kierkegaard actually wrote, "It is quite true what philosophy says; that life must be understood backwards. But then one forgets the other principle: that it must be lived forwards. Which principle, the more one thinks it through, ends exactly with the thought that temporal life can never properly be understood precisely because I can at no instant find complete rest in which to adopt a position: backwards."

The Encyclopaedia of religion and ethics had an article about him in 1908. The article began:

“The life of Søren Kierkegaard has but few points of contact with the external world; but there were, in particular, three occurrences — a broken engagement, and attack by a comic paper, and the use of a word by H.L. Martensen — which must be referred to as having wrought with extraordinary effect upon his peculiarly sensitive and high - strung nature. The intensity of his inner life, again — which finds expression in his published works, and even more directly in his notebooks and diaries (also published) — cannot be properly understood without some reference to his father.”

Theodor Haecker wrote an essay titled, Kierkegaard and the Philosophy of Inwardness in 1913 and David F. Swenson wrote a biography of Søren Kierkegaard in 1920. Lee M. Hollander translated parts of Either / Or, Fear and Trembling, Stages on Life's Way, and Preparations for the Christian Life (Practice in Christianity) into English in 1923, with little impact. Swenson said,

It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world."

Hermann Gottsche published Kierkegaard's Journals in 1905. It had taken academics 50 years to arrange his journals. Kierkegaard's main works were translated into German by Christoph Schrempf from 1909 onwards. Emmanuel Hirsch released a German edition of Kierkegaard's collected works from 1950 onwards. Both Harald Hoffding's and Schrempf's books about Kierkegaard were reviewed in 1892.

There are two volumes from the pen of H. Hoffding, both of which are to be praised on account of the fresh and rich language and the clear, incisive exposition. They treat of Soren Kierkegaard, the poet - philosopher of melancholy, of abrupt transitions, of paradoxes, the preacher of the ‘true’ Christianity, full of suffering, and to which the world is a stranger; and Rousseau, the herald of humanity, good as it is by nature, the despiser of men, bad, artificial, and over refined as culture had made them. In both these men, the dependence of philosophical thinking upon the individual personality and experience of the thinker is strongly marked. An understanding of either one, therefore, must be based upon an analysis of his personality; and the historian must above all things - as is the case with Hoffding in a high degree - possess psychological insight and the ability to enter into another’s personality and to feel and think from his standpoint. But it is just this which makes the subjectivity of the historian paramount, and thereby increases the probability of contradiction. That which is to one psychologically possible, or seems absolutely necessary, is unthinkable to another on account of his mental peculiarity. Thus, for instance, Chr. Schrempf, takes an entirely different standpoint in regard to Kierkegaard. He thinks that, if one regards him only from the point of view which Hoffding adopts, the great Dane can neither be rightly understood nor appreciated. Schremph - in opposition to Hoffding - agrees with Kierkegaard in the position that melancholy, ‘dread’ of oneself, of the world, and of God is the dominating frame of mind of every man who has become intensively conscious of himself. I, for my part, must take exception to the characterization of Rousseau. The pathological element in him is much too little emphasized. Kierkegaard may have been more strongly encumbered in a certain sense by the influence of heredity, still he possesses what Rousseau completely lacks, namely, a great strength of will and a strong power of concentration. The Philosophical Review, Volume I, Ginn and Company 1892 p. 282 - 283

In the 1930s, the first academic English translations, by Alexander Dru, David F. Swenson, Douglas V. Steere and Walter Lowrie appeared, under the editorial efforts of Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams, one of the members of the Inklings. Thomas Henry Croxall, another early translator, Lowrie and Dru all hoped that people would not just read about Kierkegaard but would actually read his works. Dru published an English translation of Kierkegaard's Journals in 1958; Alastair Hannay translated some of Kierkegaard's works. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong translated his works more than once. The first volume of their first version of the Journals and Papers (Indiana, 1967 – 1978) won the 1968 U.S. National Book Award in category Translation. They both dedicated their lives to the study of Soren Kierkegaard and his works, which are maintained at the Howard V. and Edna H. Hong Kierkegaard Library.

Kierkegaard's comparatively early and manifold philosophical and theological reception in Germany was one of the decisive factors of expanding his works' influence and readership throughout the world. Important for the first phase of his reception in Germany was the establishment of the journal Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Ages) in 1922 by a heterogeneous circle of Protestant theologians: Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Rudolf Bultmann and Friedrich Gogarten.Their thought would soon be referred to as dialectical theology. At roughly the same time, Kierkegaard was discovered by several proponents of the Jewish - Christian philosophy of dialogue in Germany, namely by Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner and Franz Rosenzweig. In addition to the philosophy of dialogue, existential philosophy has its point of origin in Kierkegaard and his concept of individuality. Martin Heidegger sparsely refers to Kierkegaard in Being and Time (1927), obscuring how much he owes to him. In 1935, Karl Jaspers emphasized Kierkegaard's (and Nietzsche's) continuing importance for modern philosophy. Walter Kaufmann discussed Sartre, Jaspers and Heidegger in relation to Kierkegaard, and Kierkegaard in relation to the crisis of religion.

Kierkegaard has been called a philosopher, a theologian, the Father of Existentialism, both atheistic and theistic variations, a literary critic, a social theorist, a humorist, a psychologist and a poet. Two of his influential ideas are "subjectivity" and the notion popularly referred to as "leap of faith". However, the Danish equivalent to the English phrase "leap of faith" does not appear in the original Danish nor is the English phrase found in current English translations of Kierkegaard's works. Kierkegaard does mention the concepts of "faith" and "leap" together many times in his works.

The leap of faith is his conception of how an individual would believe in God or how a person would act in love. Faith is not a decision based on evidence that, say, certain beliefs about God are true or a certain person is worthy of love. No such evidence could ever be enough to completely justify the kind of total commitment involved in true religious faith or romantic love. Faith involves making that commitment anyway. Kierkegaard thought that to have faith is at the same time to have doubt. So, for example, for one to truly have faith in God, one would also have to doubt one's beliefs about God; the doubt is the rational part of a person's thought involved in weighing evidence, without which the faith would have no real substance. Someone who does not realize that Christian doctrine is inherently doubtful and that there can be no objective certainty about its truth does not have faith but is merely credulous. For example, it takes no faith to believe that a pencil or a table exists, when one is looking at it and touching it. In the same way, to believe or have faith in God is to know that one has no perceptual or any other access to God, and yet still has faith in God. Kierkegaard writes, "doubt is conquered by faith, just as it is faith which has brought doubt into the world".

Kierkegaard also stresses the importance of the self, and the self's relation to the world, as being grounded in self - reflection and introspection. He argued in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity." This has to do with a distinction between what is objectively true and an individual's subjective relation (such as indifference or commitment) to that truth. People who in some sense believe the same things may relate to those beliefs quite differently. Two individuals may both believe that many of those around them are poor and deserve help, but this knowledge may lead only one of them to decide to actually help the poor. This is how Kierkegaard put it:

"Since I am not totally unfamiliar with what has been said and written about Christianity, I could presumably say a thing or two about it. I shall, however, not do so here but merely repeat that there is one thing I shall beware of saying about it: that it is true to a certain degree. It is indeed just possible that Christianity is the truth; it is indeed just possible that someday there will be a judgment in which the separation will hinge on the relation of inwardness to Christianity. Suppose that someone stepped forward who had to say, “Admittedly I have not believed, but I have so honored Christianity that I have spent every hour of my life pondering it.” Or suppose that someone came forward of whom the accuser has to say, “He has persecuted the Christians,” and the accused one responded, “Yes, I acknowledge it; Christianity has so inflamed my soul that, simply because I realized its terrible power, I have wanted nothing else than to root it out of the world.” Or suppose that someone came forward of whom the accuser had to say, “He has renounced Christianity,” and the accused one responded, “Yes, it is true, for I perceived that Christianity was such a power that if I gave it one finger it would take all of me, and I could not belong to it completely.” But suppose now, that eventually an active assistant professor came along at a hurried and bustling pace and said something like this, “I am not like those three; I have not only believed but have even explained Christianity and have shown that what was proclaimed by the apostles and appropriated in the first centuries is true only to a certain degree. On the other hand, through speculative understanding I have shown how it is the true truth, and for that reason I must request suitable remuneration for my meritorious services to Christianity. Of these four, which position would be the most terrible?"

In other words he says:

"Who has the more difficult task: the teacher who lectures on earnest things a meteor's distance from everyday life - or the learner who should put it to use?" Kierkegaard, Soren. Works of Love. Harper & Row, Publishers. New York, N.Y. 1962. p. 62

Kierkegaard primarily discusses subjectivity with regard to religious matters. As already noted, he argues that doubt is an element of faith and that it is impossible to gain any objective certainty about religious doctrines such as the existence of God or the life of Christ. The most one could hope for would be the conclusion that it is probable that the Christian doctrines are true, but if a person were to believe such doctrines only to the degree they seemed likely to be true, he or she would not be genuinely religious at all. Faith consists in a subjective relation of absolute commitment to these doctrines.

Kierkegaard's famous philosophical 20th century critics include Theodor Adorno and Emmanuel Levinas. Atheistic philosophers such as Jean - Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger supported many aspects of Kierkegaard's philosophical views, but rejected some of his religious views.

One critic wrote that Adorno's book Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic is "the most irresponsible book ever written on Kierkegaard" because Adorno takes Kierkegaard's pseudonyms literally, and constructs a philosophy which makes him seem incoherent and unintelligible. Another reviewer says that "Adorno is [far away] from the more credible translations and interpretations of the Collected Works of Kierkegaard we have today."

Levinas' main attack on Kierkegaard focused on his ethical and religious stages, especially in Fear and Trembling. Levinas criticizes the leap of faith by saying this suspension of the ethical and leap into the religious is a type of violence. He states:

"Kierkegaardian violence begins when existence is forced to abandon the ethical stage in order to embark on the religious stage, the domain of belief. But belief no longer sought external justification. Even internally, it combined communication and isolation, and hence violence and passion. That is the origin of the relegation of ethical phenomena to secondary status and the contempt of the ethical foundation of being which has led, through Nietzsche, to the amoralism of recent philosophies."

Levinas pointed to the Judeo - Christian belief that it was God who first commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and that an angel commanded Abraham to stop. If Abraham were truly in the religious realm, he would not have listened to the angel's command and should have continued to kill Isaac. "Transcending ethics" seems like a loophole to excuse would - be murderers from their crime and thus is unacceptable. One interesting consequence of Levinas' critique is that it seemed to reveal that Levinas viewed God as a projection of inner ethical desire rather than an absolute moral agent.

Sartre objected to the existence of God: If existence precedes essence, it follows from the meaning of the term sentient that a sentient being cannot be complete or perfect. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre's phrasing is that God would be a pour - soi (a being - for - itself; a consciousness) who is also an en - soi (a being - in - itself; a thing) which is a contradiction in terms. Critics of Sartre rebutted this objection by stating that it rests on a false dichotomy and a misunderstanding of the traditional Christian view of God.

Sartre agreed with Kierkegaard's analysis of Abraham undergoing anxiety (Sartre calls it anguish), but claimed that God told Abraham to do it. In his lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism, Sartre wondered whether Abraham ought to have doubted whether God actually spoke to him. In Kierkegaard's view, Abraham's certainty had its origin in that 'inner voice' which cannot be demonstrated or shown to another ("The problem comes as soon as Abraham wants to be understood"). To Kierkegaard, every external "proof" or justification is merely on the outside and external to the subject. Kierkegaard's proof for the immortality of the soul, for example, is rooted in the extent to which one wishes to live forever.

Many 20th century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, and theologians drew concepts from Kierkegaard, including the notions of angst, despair and the importance of the individual. His fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, in large part because the ascendant existentialist movement pointed to him as a precursor, although later writers celebrated him as a highly significant and influential thinker in his own right. Since Kierkegaard was raised as a Lutheran, he was commemorated as a teacher in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 11 November and in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 8 September.

Philosophers and theologians influenced by Kierkegaard include Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Barth, Simone de Beauvoir, Niels Bohr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Emil Brunner, Martin Buber, Rudolf Bultmann, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau - Ponty, Reinhold Niebuhr, Franz Rosenzweig, Jean - Paul Sartre, Joseph Soloveitchik, Paul Tillich, Malcolm Muggeridge, Thomas Merton, Miguel de Unamuno. Paul Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism in the philosophy of science was inspired by Kierkegaard's idea of subjectivity as truth. Ludwig Wittgenstein was immensely influenced and humbled by Kierkegaard, claiming that "Kierkegaard is far too deep for me, anyhow. He bewilders me without working the good effects which he would in deeper souls". Karl Popper referred to Kierkegaard as "the great reformer of Christian ethics, who exposed the official Christian morality of his day as anti - Christian and anti - humanitarian hypocrisy".

"The comparison between Nietzsche and Kierkegaard that has become customary, but is no less questionable for that reason, fails to recognize, and indeed out of a misunderstanding of the essence of thinking, that Nietzsche as a metaphysical thinker preserves a closeness to Aristotle. Kierkegaard remains essentially remote from Aristotle, although he mentions him more often. For Kierkegaard is not a thinker but a religious writer, and indeed not just one among others, but the only one in accord with the destining belonging to his age. Therein lies his greatness, if to speak in this way is not already a misunderstanding." Heidegger: Nietzsche's Word, "God is Dead." p. 94

Dear reader! Kierkegaard might say; pray be so good as to look for my thinking in these pages - not for Nietzsche's, Brath's or Heidegger's, De Tocqueville's, or anyone else's. And least of all, dear reader, fancy that if you should find that a few others have said, too, what I have said, that makes it true. Oh, least of all suppose that numbers can create some small presumption of the truth of an idea. What I would have you ask, dear reader, is not whether I am in good company: to be candid, I should have much preferred to stand alone, as a matter of principle; and besides I do not like the men whom the kissing Judases insist on lumping me. Rather ask yourself if I am right. And if I am not, then for heaven's sake do not pretend that I am, emphasizing a few points that are reasonable, even if not central to my thought, while glossing over those ideas which you do not like, or which, in retrospect, are plainly wrong, although I chose to take my stand on them. Do not forget, dear reader, that I made a point of taking for my motto (in my Philosophical Scraps): 'Better well hung than ill wed!'

- Walter Kaufmann Introduction to The Present Age, Soren Kierkegaard, Dru 1940, 1962 p. 18 - 19

Contemporary philosophers such as Emmanuel Lévinas, Hans - Georg Gadamer, Jacques Derrida, Jürgen Habermas, Alasdair MacIntyre and Richard Rorty, although sometimes highly critical, have also adapted some Kierkegaardian insights. Hilary Putnam admires Kierkegaard, "for his insistence on the priority of the question, 'How should I live?'".

Kierkegaard has also had a considerable influence on 20th century literature. Figures deeply influenced by his work include W.H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Don DeLillo, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka, David Lodge, Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Rainer Maria Rilke, J.D. Salinger and John Updike.

Kierkegaard had a profound influence on psychology. He is widely regarded as the founder of Christian psychology and of existential psychology and therapy. Existentialist (often called "humanistic") psychologists and therapists include Ludwig Binswanger, Viktor Frankl, Erich Fromm, Carl Rogers and Rollo May. May based his The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard's sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age critiques modernity. Ernest Becker based his 1974 Pulitzer Prize book, The Denial of Death, on the writings of Kierkegaard, Freud and Otto Rank. Kierkegaard is also seen as an important precursor of postmodernism. In popular culture, he was the subject of serious television and radio programs; in 1984, a six part documentary Sea of Faith: Television series presented by Don Cupitt featured a episode on Kierkegaard, while on Maundy Thursday in 2008, Kierkegaard was the subject of discussion of the BBC Radio 4 program presented by Melvyn Bragg, In Our Time.

Kierkegaard predicted his posthumous fame, and foresaw that his work would become the subject of intense study and research. In his journals, he wrote:

"What the age needs is not a genius — it has had geniuses enough, but a martyr, who in order to teach men to obey would himself be obedient unto death. What the age needs is awakening. And therefore someday, not only my writings but my whole life, all the intriguing mystery of the machine will be studied and studied. I never forget how God helps me and it is therefore my last wish that everything may be to his honor."

In 1784 Immanuel Kant challenged the thinkers of Europe to think for themselves.

"Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why so great a proportion of men, long after nature has released them from alien guidance (natura - liter maiorennes), nonetheless gladly remain in lifelong immaturity, and why it is so easy for others to establish themselves as their guardians. It is so easy to be immature. If I have a book to serve as my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to determine my diet for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome work for me. The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone. Now this danger is not actually so great, for after falling a few times they would in the end certainly learn to walk; but an example of this kind makes men timid and usually frightens them out of all further attempts."

In 1854 Søren Kierkegaard wrote a note to “My Reader” of a similar nature.

"When a man ventures out so decisively as I have done, and upon a subject moreover which affects so profoundly the whole of life as does religion, it is to be expected of course that everything will be done to counteract his influence, also by misrepresenting, falsifying what he says, and at the same time his character will in every way be at the mercy of men who count that they have no duty towards him but that everything is allowable. Now, as things commonly go in this world, the person attacked usually gets busy at once to deal with every accusation, every falsification, every unfair statement, and in this way is occupied early and late in counterattacking the attack. This I have no intention of doing. ... I propose to deal with the matter differently, I propose to go rather more slowly in counteracting all this falsification and misrepresentation, all these lies and slanders, all the prate and twaddle. Partly because I learn from the New Testament that the occurrence of such things is a sign that one is on the right road, so that obviously I ought not to be exactly in a hurry to get rid of it, unless I wish as soon as possible to get on the wrong road. And partly because I learn from the New Testament that what may temporally be called a vexation, from which according to temporal concepts one might try to be delivered, is eternally of value, so that obviously I ought not to be exactly in a hurry to try to escape, if I do not wish to hoax myself with regard to the eternal. This is the way I understand it; and now I come to the consequence which ensues for thee. If thou really has ever had an idea that I am in the service of something true — well then, occasionally there shall be done on my part what is necessary, but only what is strictly necessary to thee, in order that , if thou wilt exert thyself and pay due attention, thou shalt be able to withstand the falsifications and misrepresentations of what I say, and all the attacks upon my character — but thy indolence, dear reader, I will not encourage. If thou does imagine that I am a lackey, thou hast never been my reader; if thou really art my reader, thou wilt understand that I regard it as my duty to thee that thou art put to some effort, if thou art not willing to have the falsifications and misrepresentations, the lies and slanders, wrest from thee the idea that I am in the service of something true."