<Back to Index>

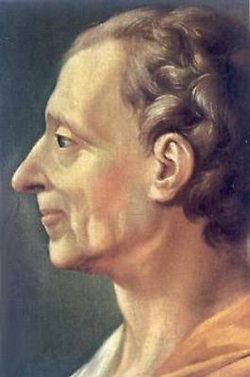

- Political Philosopher Charles - Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, 1689

- General of the French and Russian Army and Strategist Antoine - Henri, baron Jomini, 1779

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 1689 – 10 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French social commentator and political thinker who lived during the Enlightenment. He is famous for his articulation of the theory of separation of powers, which is taken for granted in modern discussions of government and implemented in many constitutions throughout the world. He was largely responsible for the popularization of the terms feudalism and Byzantine Empire.

He was born at the Château de la Brède in the southwest of France. His father, Jacques de Secondat, was a soldier with a long noble ancestry. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel who died when Charles de Secondat was seven, was a female inheritor of a large monetary inheritance who brought the title of barony of La Brède to the Secondat family. After having studied at the Catholic College of Juilly, Charles - Louis de Secondat married. His wife, Jeanne de Lartigue, a Protestant, brought him a substantial dowry when he was 26. The next year, he inherited a fortune upon the death of his uncle, as well as the title Baron de Montesquieu and Président à Mortier in the Parliament of Bordeaux.

Montesqueieu's early life occurred at a time of significant governmental change. On the nearby British Isles, England had declared itself a constitutional monarchy in the wake of its Glorious Revolution (1688 – 89), and had joined with Scotland in the Union of 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. In France the long reigning Louis XIV died in 1715 and was succeeded by the five year old Louis XV. These national transformations impacted Montesquieu greatly; he would later refer to them repeatedly in his work.

He achieved literary success with the publication of his Lettres persanes (Persian Letters, 1721), a satire based on the imaginary correspondence of a Persian visitor to Paris, pointing out the absurdities of contemporary society. He next published Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Considerations on the Causes of the Grandeur and Decadence of the Romans, 1734), considered by some scholars a transition from The Persian Letters to his master work. De l'Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws) was originally published anonymously in 1748 and quickly rose to a position of enormous influence. In France, it met with an unfriendly reception from both supporters and opponents of the regime. The Catholic Church banned l'Esprit – along with many of Montesquieu's other works – in 1751 and included it on the Index of Prohibited Books. It received the highest praise from the rest of Europe, especially Britain.

Montesquieu was also highly regarded in the British colonies in North America as a champion of British liberty (though not of American independence). Political scientist Donald Lutz found that Montesquieu was the most frequently quoted authority on government and politics in colonial pre - revolutionary British America, cited more by the American founders than any source except for the Bible. Following the American revolution, Montesquieu's work remained a powerful influence on many of the American founders, most notably James Madison of Virginia, the "Father of the Constitution". Montesquieu's philosophy that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another" reminded Madison and others that a free and stable foundation for their new national government required a clearly defined and balanced separation of powers.

Besides composing additional works on society and politics, Montesquieu traveled for a number of years through Europe including Austria and Hungary, spending a year in Italy and 18 months in England before resettling in France. He was troubled by poor eyesight, and was completely blind by the time he died from a high fever in 1755. He was buried in the Église Saint - Sulpice, Paris.

Montesquieu's philosophy of history minimized the role of individual persons and events. He expounded the view in Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence that each historical event was driven by a principal movement:

It is not chance that rules the world. Ask the Romans, who had a continuous sequence of successes when they were guided by a certain plan, and an uninterrupted sequence of reverses when they followed another. There are general causes, moral and physical, which act in every monarchy, elevating it, maintaining it, or hurling it to the ground. All accidents are controlled by these causes. And if the chance of one battle — that is, a particular cause — has brought a state to ruin, some general cause made it necessary for that state to perish from a single battle. In a word, the main trend draws with it all particular accidents.

In discussing the transition from the Republic to the Empire, he suggested that if Caesar and Pompey had not worked to usurp the government of the Republic, other men would have risen in their place. The cause was not the ambition of Caesar or Pompey, but the ambition of man.

Montesquieu is credited among the precursors of anthropology, including Herodotus and Tacitus, to be among the first to extend comparative methods of classification to the political forms in human societies. Indeed, the French political anthropologist Georges Balandier considered Montesquieu to be "the initiator of a scientific enterprise that for a time performed the role of cultural and social anthropology". According to social anthropologist D.F. Pocock, Montesquieu's 'On the Spirit of Laws' "is the first consistent attempt to survey the varieties of human society, to classify and compare them and, within society, to study the inter - functioning of institutions". Montesquieu's political anthropology gave rise to his theories on government.

Montesquieu's most influential work divided French society into three classes (or trias politica, a term he coined): the monarchy, the aristocracy and the commons. Montesquieu saw two types of governmental power existing: the sovereign and the administrative. The administrative powers were the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. These should be separate from and dependent upon each other so that the influence of any one power would not be able to exceed that of the other two, either singly or in combination. This was a radical idea because it completely eliminated the three Estates structure of the French Monarchy: the clergy, the aristocracy and the people at large represented by the Estates - General, thereby erasing the last vestige of a feudalistic structure.

Likewise, there were three main forms of government, each supported by a social "principle": monarchies (free governments headed by a hereditary figure, e.g., king, queen, emperor), which rely on the principle of honor; republics (free governments headed by popularly elected leaders), which rely on the principle of virtue; and despotisms (enslaved governments headed by dictators), which rely on fear. The free governments are dependent on fragile constitutional arrangements. Montesquieu devotes four chapters of The Spirit of the Laws to a discussion of England, a contemporary free government, where liberty was sustained by a balance of powers. Montesquieu worried that in France the intermediate powers (i.e., the nobility) which moderated the power of the prince were being eroded. These ideas of the control of power were often used in the thinking of Maximilien de Robespierre.

Montesquieu was somewhat ahead of his time in advocating major reform of slavery in The Spirit of the Laws. As part of his advocacy he presented a satirical hypothetical list of arguments for slavery, which has been open to contextomy. However, like many of his generation, Montesquieu also held a number of views that might today be judged controversial. He firmly accepted the role of a hereditary aristocracy and the value of primogeniture, and while he endorsed the idea that a woman could head a state, he held that she could not be effective as the head of a family.

Another example of Montesquieu's anthropological thinking, outlined in The Spirit of the Laws and hinted at in Persian Letters, is his meteorological climate theory, which holds that climate may substantially influence the nature of man and his society. By placing an emphasis on environmental influences as a material condition of life, Montesquieu prefigured modern anthropology's concern with the impact of material conditions, such as available energy sources, organized production systems and technologies, on the growth of complex socio - cultural systems.

He goes so far as to assert that certain climates are superior to others, the temperate climate of France being ideal. His view is that people living in very warm countries are "too hot - tempered," while those in northern countries are "icy" or "stiff." The climate of middle Europe is therefore optimal. On this point, Montesquieu may well have been influenced by a similar pronouncement in The Histories of Herodotus, where he makes a distinction between the 'ideal' temperate climate of Greece as opposed to the overly cold climate of Scythia and the overly warm climate of Egypt. This was a common belief at the time, and can also be found within the medical writings of Herodotus' times, including the 'On Airs, Waters, Places' of the Hippocratic corpus. One can find a similar statement in Germania by Tacitus, one of Montesquieu's favorite authors. However, the earlier works that most closely resemble Montesquieu's complex climate theory are the Muqaddimah (1377) by the Arab sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, and The Travels of Sir John Chardin in Persia and the Orient (1711) by the French traveler Jean Chardin.

From a sociological perspective Louis Althusser, in his analysis of Montesquieu's revolution in method, alluded to the seminal character of anthropology's inclusion of material factors, such as climate, in the explanation of social dynamics and political forms. Examples of certain climatic and geographical factors giving rise to increasingly complex social systems include those that were conducive to the rise of agriculture and the domestication of wild plants and animals.

Antoine - Henri, baron Jomini (6 March 1779 – 24 March 1869) was a general in the French and later in the Russian service, and one of the most celebrated writers on the Napoleonic art of war. According to the historian John Shy, Jomini "deserves the dubious title of founder of modern strategy." Jomini's ideas were a staple at military academies. The senior generals of the American Civil War — those who had attended West Point — were well versed in Jomini's theories.

Jomini was born in Payerne in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland, on 6 March 1779, where his father served as mayor. The Jominis "were an old Swiss family" of Italian descent with a decidedly pro-French outlook. As a young boy, Jomini "was fascinated by soldiers and the art of war," and hoped to join the military, but his parents pushed him towards a career in business. As a result, Jomini entered a business school in Aarau at the age of 14.

In April 1795, Jomini left school and went to work at the banking house of Monsieurs Preiswerk in Basle. In 1796, he moved to Paris where he worked first at another banking house and then as a stockbroker. After a short time in banking, however, "Jomini convinced himself that the tedious life of a banker was not to be compared with the life afforded in French Army," and decided to become a military officer as soon as he found an opportunity.

In 1798, after the establishment of the Helvetic Republic, Jomini became an "eager revolutionary", following the example of Frédéric - César de La Harpe and found a position in the new Swiss government as a secretary for the Minister of War with the rank of captain. In 1799, after being promoted to the rank of major, Jomini took responsibility for reorganizing the operations of the ministry. In that capacity, he standardized many procedures, and used his position "to experiment with organizational systems and strategies."

After the peace of Lunéville in 1801, Jomini returned to Paris, where he worked for a military equipment manufacturer. He found the job uninteresting, and spent most of his time preparing his first book on military theory: Traité des grandes operations militaires (Treatise on Major Military Operations). Michel Ney, one of Napoleon's top generals, read the book in 1803 and subsidized its publication. The book appeared in several volumes from 1804 to 1810, and was "quickly translated and widely discussed" throughout Europe.

In 1805, Jomini served in the campaign of Austerlitz as a volunteer aide - de - camp on Ney's personal staff, and in December of that year, he was offered a commission as a colonel in the French Army. He joined without hesitation and served on Ney's staff. Jomini fought with Ney at the Battle of Ulm and served as his senior aide - de - camp at the Battle of Jena.

In 1806 Jomini published his views as to the conduct of the impending war with Prussia. This, along with his knowledge of Frederick the Great's campaigns, which Jomini had described in the Traité, led Napoleon to attach him to his own headquarters. Jomini was present with Napoleon at the Jena and at Eylau he won the cross of the Legion of Honor.

After the peace of Tilsit Jomini was made chief of the staff to Ney and created a Baron. In the Spanish campaign of 1808 his advice was often of the highest value to the marshal, but Jomini quarreled with his chief, and was left almost at the mercy of his numerous enemies, especially Louis Alexandre Berthier, the emperor's chief of staff.

Overtures had been made to him, as early as 1807, to enter the Russian service, but Napoleon, hearing of his intention to leave the French army, compelled him to remain in the service with the rank of general of brigade.

For some years thereafter Jomini held both a French and a Russian commission, with the consent of both sovereigns. But when war between France and Russia broke out, he was in a difficult position, which he dealt with by taking a non - combat command on the line of communication.

Jomini was thus engaged when the retreat from Moscow and the uprising of Prussia transferred the seat of war to central Germany. He promptly rejoined Ney, took part in the Battle of Lützen. As chief of the staff of Ney's group of corps, he rendered distinguished services before and at the Battle of Bautzen, and was recommended for the rank of general of division. Berthier, however, not only erased Jomini's name from the list but put him under arrest and censured him in army orders for failing to supply certain staff reports that had been called for.

How far Jomini was responsible for certain misunderstandings which prevented the attainment of all the results hoped for from Ney's attack at Bautzen, we cannot be sure. But the pretext for censure was in Jomini's own view trivial and baseless, and during the armistice Jomini did as he had intended to do in 1809 – 1810, and went into the Russian service. As things then were, this was tantamount to deserting to the enemy, and so it was regarded by many in the French army, and by not a few of his new comrades. It must be observed, in Jomini's defense, that he had for years held a dormant commission in the Russian army and that he had declined to take part in the invasion of Russia in 1812. More important — and a point that Napoleon commented upon — was the fact that he was a Swiss citizen, not a Frenchman.

His Swiss patriotism was indeed strong, and he withdrew from the Allied Army in 1814 when he found that he could not prevent the allies' violation of Swiss neutrality. Apart from love of his own country, the desire to study, to teach and to practice the art of war was his ruling motive. At the critical moment of the battle of Eylau he had exclaimed, "If I were the Russian commander for two hours!" On joining the allies he received the rank of lieutenant general and the appointment of aide - de - camp from the tsar, and rendered important assistance during the German campaign: an accusation that he had betrayed the numbers, positions and intentions of the French to the enemy was later acknowledged by Napoleon to be without foundation. As a Swiss patriot and as a French officer, he declined to take part in the passage of the Rhine at Basel and the subsequent invasion of France.

In 1815 he was with Tsar Alexander in Paris, and attempted in vain to save the life of his old commander Ney. This defense of Ney almost cost Jomini his position in the Russian service. He succeeded, however, in overcoming the resistance of his enemies and took part in the Congress of Vienna.

After several years of retirement and literary work, Jomini resumed his post in the Russian army, and in about 1823 was made a full General. Thenceforward until his retirement in 1829 he was principally employed in the military education of the Tsarevich Nicholas (afterwards Emperor) and in the organization of the Russian staff college, which was opened in 1832 and bore its original name of the Nicholas Academy up to the October Revolution of 1917. In 1828 he was employed in the field in the Russo - Turkish War, and at the Siege of Varna he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Alexander Order.

This was his last active service. In 1829 he settled in Brussels which served as his main place of residence for the next thirty years. In 1853, after trying without success to bring about a political understanding between France and Russia, Jomini was called to St Petersburg to act as a military adviser to the Tsar during the Crimean War. He returned to Brussels upon the conclusion of peace in 1856. Later he settled at Passy near Paris. He was busily employed up to the end of his life in writing treatises, pamphlets and open letters on subjects of military art and history. In 1859 he was asked by Napoleon III to furnish a plan of campaign for the Italian War. One of his last essays dealt with the Austro - Prussian War of 1866 and the influence of the breech - loading rifle. He died at Passy only a year before the Franco - Prussian War of 1870 - 71.

Jomini's military writings are frequently analyzed: he took a didactic, prescriptive approach, reflected in a detailed vocabulary of geometric terms such as bases, strategic lines and key points. His operational prescription was fundamentally simple: put superior combat power at the decisive point. In the famous theoretical Chapter 25 of the Traité de grande tactique, he stressed the exclusive superiority of interior lines.

As one writer rather partial to Carl von Clausewitz – Jomini's great competitor in the field of military theory – put it:

Jomini was no fool, however. His intelligence, facile pen, and actual experience of war made his writings a great deal more credible and useful than so brief a description can imply. Once he left Napoleon's service, he maintained himself and his reputation primarily through prose. His writing style - unlike Clausewitz's - reflected his constant search for an audience. He dealt at length with a number of practical subjects (logistics, seapower) that Clausewitz had largely ignored. Elements of his discussion (his remarks on Great Britain and seapower, for instance, and his sycophantic treatment of Austria's Archduke Charles) are clearly aimed at protecting his political position or expanding his readership. And, one might add, at minimizing Clausewitz's, for he clearly perceived the Prussian writer as his chief competitor. For Jomini, Clausewitz's death thirty - eight years prior to his own came as a piece of rare good fortune.

Jomini took the view that the amount of force deployed should be kept to the minimum in order to lower casualties and that war was a science, not an art. Jomini stated in his book, "War in its ensemble is NOT a science, but an art. Strategy, particularly, may indeed be regulated by fixed laws resembling those of the positive sciences, but this is not true of war viewed as a whole. Among other things, combats may be mentioned as often being quite independent of scientific combinations, and they may become essentially dramatic, personal qualities and inspirations and a thousand other things frequently being the controlling elements. The passions which agitate the masses that are brought into collision, the warlike qualities of these masses, the energy and talent of their commanders, the spirit, more or less martial, of nations and epochs — in a word, every thing that can be called the poetry and metaphysics of war — will have a permanent influence on its results." . While in Russian service, Jomini tried hard to promote a more scientific approach at the general staff academy he helped to found.

Prior to the American Civil War, the translated writings of Jomini were the only works on military strategy that were taught at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His ideas, as taught by professor Dennis Hart Mahan permeated the Academy and shaped the basic military thinking of its graduates.

The regular army officers who became the general officers for both the Union and the Confederacy in the Civil war began by following Jominian principles.

However, Keegan argues that the peculiarities of American geography,

particularly in the west, forced them to move beyond his geometric

conventions and find other strategic solutions to the problems which

confronted them.