<Back to Index>

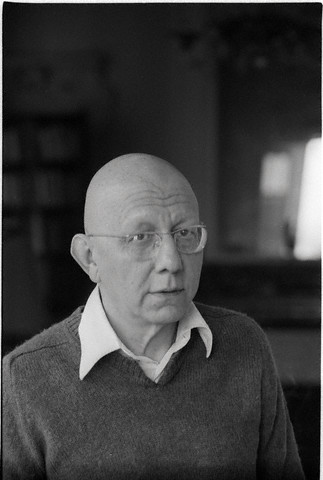

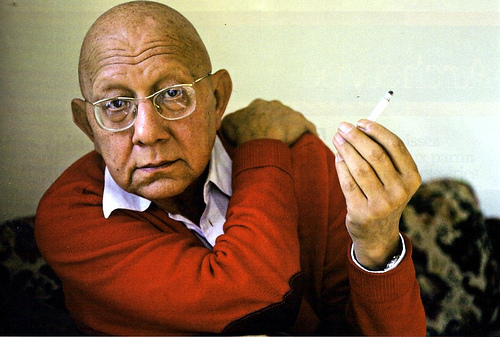

- Philosopher, Economist and Psychoanalyst Cornelius Castoriadis (Κορνήλιος Καστοριάδης), 1922

PAGE SPONSOR

Cornelius Castoriadis (Greek: Κορνήλιος Καστοριάδης; March 11, 1922 – December 26, 1997) was a French - Greek philosopher, social critic, economist, psychoanalyst, author of The Imaginary Institution of Society, and co-founder of the Socialisme ou Barbarie group.

Castoriadis was born in Constantinople and his family moved in 1922 to Athens. He developed an interest in politics after he came into contact with Marxist thought and philosophy at the age of 13. His first active involvement in politics occurred during the Metaxas Regime (1937), when he joined the Athenian Communist Youth (Kommounistiki Neolaia). In 1941 he joined the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), only to leave one year later in order to become an active Trotskyist. The latter action resulted in his persecution by both the Germans and the Communist Party. In 1944 he wrote his first essays on social science and Max Weber, which he published in a magazine named "Archive of Sociology and Ethics" (Archeion Koinoniologias kai Ithikis). During the December 1944 violent clashes between the communist led ELAS and the Papandreou government, aided by British troops, Castoriadis heavily criticized the actions of the KKE. After earning degrees in political science, economics and law from the University of Athens, he sailed to Paris, where he remained permanently, to continue his studies under a scholarship offered by the French Institute.

Once in Paris, Castoriadis joined the Trotskyist Parti Communiste Internationaliste, but broke with it by 1948. He then joined Claude Lefort and others in founding the libertarian socialist group and the journal Socialisme ou Barbarie (1949 – 1966), which included Jean - François Lyotard and Guy Debord as members for a while, and profoundly influenced the French intellectual left. Castoriadis had links with the group around C.L.R. James until 1958. Also strongly influenced by Castoriadis and Socialisme ou Barbarie were the British group and journal Solidarity and Maurice Brinton.

At the same time, he worked as an economist at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development until 1970, which was also the year when he obtained French citizenship. Consequently, his writings prior to that date were published pseudonymously, as Pierre Chaulieu, Paul Cardan, etc. Castoriadis was particularly influential in the turn of the intellectual left during the 1950s against the Soviet Union, because he argued that the Soviet Union was not a communist, but rather a bureaucratic state, which contrasted with Western powers mostly by virtue of its centralized power apparatus. His work in the OECD substantially helped his analyses. In the latter years of Socialisme ou Barbarie, Castoriadis came to reject the Marxist theories of economics and of history, especially in an essay on Modern Capitalism and Revolution (first published in Socialisme ou Barbarie, 1960 – 61; first London Solidarity English translation, 1963).

When Jacques Lacan's disputes with the International Psychoanalytical Association led to a split and the formation of the École Freudienne de Paris in 1964, Castoriadis became a member (as a non - practitioner). In 1969 Castoriadis split from the EFP with the "Quatrième groupe". He trained as a psychoanalyst and began to practice in 1974.

In his 1975 work, L'institution imaginaire de la société (Imaginary Institution of Society), and in Les carrefours du labyrinthe (Crossroads in the Labyrinth), published in 1978, Castoriadis began to develop his distinctive understanding of historical change as the emergence of irrecoverable otherness that must always be socially instituted and named in order to be recognized. Otherness emerges in part from the activity of the psyche itself. Creating external social institutions that give stable form to what Castoriadis terms the magma of social significations allows the psyche to create stable figures for the self, and to ignore the constant emergence of mental indeterminacy and alterity.

For Castoriadis, self - examination, as in the ancient Greek tradition, could draw upon the resources of modern psychoanalysis. Autonomous individuals — the essence of an autonomous society — must continuously examine themselves and engage in critical reflection. He writes:

...psychoanalysis can and should make a basic contribution to a politics of autonomy. For, each person's self - understanding is a necessary condition for autonomy. One cannot have an autonomous society that would fail to turn back upon itself, that would not interrogate itself about its motives, its reasons for acting, its deep - seated [profondes] tendencies. Considered in concrete terms, however, society doesn't exist outside the individuals making it up. The self - reflective activity of an autonomous society depends essentially upon the self - reflective activity of the humans who form that society.

Castoriadis was not calling for every individual to undergo psychoanalysis, per se. Rather, by reforming education and political systems, individuals would be increasingly capable of critical self- and social reflexion. He offers: "if psychoanalytic practice has a political meaning, it is solely to the extent that it tries, as far as it possibly can, to render the individual autonomous, that is to say, lucid concerning her desire and concerning reality, and responsible for her acts: holding herself accountable for what she does."

In his 1980 Facing The War text, he took the view that Russia had become the primary world military power. To sustain this, in the context of the visible economic inferiority of the Soviet Union in the civilian sector, he proposed that the society may no longer be dominated by the party - state bureaucracy but by a "stratocracy" - a separate and dominant military sector with expansionist designs on the world. He further argued that this meant there was no internal class dynamic which could lead to social revolution within Russian society and that change could only occur through foreign intervention.

In 1980, he joined the faculty of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

On December 26, 1997, he died from complications following heart surgery.

Edgar Morin proposed that Castoriadis' work will be remembered for its remarkable continuity and coherence as well as for its extraordinary breadth which was "encyclopaedic" in the original Greek sense, for it offered us a "paideia," or education, that brought full circle our cycle of otherwise compartmentalized knowledge in the arts and sciences. Castoriadis wrote essays on mathematics, physics, biology, anthropology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, society, economics, politics, philosophy and art.

One of Castoriadis' many important contributions to social theory was the idea that social change involves radical discontinuities that cannot be understood in terms of any determinate causes or presented as a sequence of events. Change emerges through the social imaginary without determinations, but in order to be socially recognized must be instituted as revolution. Any knowledge of society and social change “can exist only by referring to, or by positing, singular entities… which figure and presentify social imaginary significations.”

Castoriadis used traditional terms as much as possible, though consistently redefining them. Further, some of his terminology changed throughout the later part of his career, with the terms gaining greater consistency but breaking from their traditional meaning (neologisms). When reading Castoriadis, it is helpful to understand what he means by the terms he uses, since he does not redefine the terms in every piece where he employs them. Here are a few.

The concept of autonomy appears to be a key theme in his early postwar writings and he continued to elaborate on its meaning, applications and limits until his death, gaining him the title of "Philosopher of Autonomy". The word itself is of Greek origin, with auto meaning 'by-itself' and nomos meaning law, defining the condition of creating one's own laws, whether as an individual or a whole society. Castoriadis noticed that while all societies create their own institutions (laws, traditions and behaviors), autonomous societies are those in which their members are aware of this fact, and explicitly self - institute (αυτο - νομούνται). In contrast, the members of heteronomous societies (hetero = others) attribute their imaginaries to some extra - social authority (i.e. God, ancestors, historical necessity).

This relates to what he identified as the need of societies to legitimize their laws, or explain why their laws are good and just. Tribal societies for example did that through religion, believing that the laws were given to them by a super - natural ancestor or god and so must be true. Capitalist societies legitimize their system (capitalism) through 'reason', claiming that their system makes logical sense. Castoriadis observes that nearly all such efforts are tautological in that they legitimize a system through rules defined by the system itself. So just like the Old Testament and the Koran claim that 'There is only one God, God', capitalist societies first define what logic is: the maximization of utility and minimization of cost, and then base their system on that logic.

As he explains in one of his lectures in the Greek village of Leonidio in 1984, many newly founded societies start from an autonomous state which is usually in the form of direct democracy, like the town hall meetings during the American Independence and the local assemblies of the Paris Commune. What they end up with however is a form of governance by which, the citizens, do not legislate directly but delegate this power to a group of experts who remain in power, largely unchecked by official means, for a number of years. The ancient Greeks on the other hand developed a system of continuous autonomy where the people (demos) voted constantly on matters of government and law and where the elected rulers, the Archons, were mainly asked to enforce them. In such a system, courts of law were governed by common citizens who were appointed to the degree of judge briefly and army generals were voted in by the people and had to convince them of the correctness of their decisions. Taking some poetic license to expand this point he says that in this system, the president of the national treasury could have been a Phoenician slave, since he would only be asked to implement the rulings of the demos.

Castoriadis' writings delve at length into the philosophy and politics of the ancient Greeks who, as a true autonomous society knew that laws are man - made and legitimization tautological. They challenged these laws on a constant basis and yet obeyed them to the same degree (even to the extent of enforcing capital punishment) proving that autonomous societies can indeed exist.

The term imaginary originates in the writings of the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan and is strongly associated with Castoriades' work. To understand it better we might think of its usual context, the "imaginary foundation of societies". By that, Castoriadis means that societies, together with their laws and legalizations, are founded upon a basic conception of the world and man's place in it. Traditional societies had elaborate imaginaries, expressed through various creation myths, by which they explained how the world came to be and how it is sustained. Capitalism did away with this mythic imaginary by replacing it with what it claims to be pure reason (as examined above). That same imaginary is, interestingly enough, the foundation of its opposing ideology, Communism. By that measure he observes, first in his main criticism of Marxism, titled the Imaginary Institution of Society, as well as speaking in Brussels, that these two systems are more closely related than was previously thought, since they share the same industrial revolution type imaginary: that of a rational society where man's welfare is materially measurable and infinitely improvable through the expansion of industries and advancements in science. In this respect Marx failed to understand that technology is not, as he claimed, the main drive of social change, since we have historical examples where societies possessing near identical technologies formed very different relations to them. An example given in the book are France and England during the industrial revolution with the second being much more liberal than the first.

Similarly, In the issue of ecology he observes that the problem facing our environment are only present within the capitalist imaginary that values the continuous expansion of industries. Trying to solve it by changing or managing these industries better might fail, since it essentially acknowledges this imaginary as real, thus perpetuating the problem.

So, imaginaries are directly responsible for all aspects of culture. The Greeks had an imaginary by which the world stems from Chaos and the ancient Jews an imaginary by which the world stems from the will of a pre - existing entity, God. The former developed therefore a system of immediate democracy where the laws where ever changing according the people's will while the second a theocratic system according to which man is in an eternal quest to understand and enforce the will of God.

This is a concept that one encounters frequently in Castoriades work (in all the references above for example). According to that, the Greeks developed an imaginary by which the world is a product of Chaos, as narrated by both Homer and Hesiod. The word has since been promoted to a scientific term, but Castoriadis is inclined to believe that although the Greeks had sometimes expressed Chaos in that way (as a system too complex to be understood), they mainly referred to it as nothingness. He then concludes what made the ancient Greeks different to other nations is exactly that core imaginary, which essentially says, that if the world is created out of nothing then man can indeed, in his brief time on earth, model it as he sees fit, without trying to conform on some preexisting order like a divine law. He contrasted that sharply to the Biblical imaginary, which sustains all Judaic societies to this day, according to which, in the beginning of the world there was a God, a willing entity and man's position therefore is to understand that Will and act accordingly.

Castoriadis views the political organization of the ancient Greek city states as a model of an autonomous society. He argues that their direct democracy was not based, as many assume, in the existence of slaves and/or the geography of Greece, which forced the creation of small city states, since many other societies had these preconditions but did not create democratic systems. Same goes for colonization since the neighboring Phoenicians, who had a similar expansion in the Mediterranean, were monarchical till their end. During this time of colonization however, around the time of Homer's Epic poems, we observe for the first time that the Greeks instead of transferring their mother city's social system to the newly established colony, they, for the first time in known history, legislate anew from the ground up. What also made the Greeks special was the fact that, following above, they kept this system as a perpetual autonomy which led to direct democracy.

This phenomenon of autonomy is again present in the emergence of the states of northern Italy during the Renaissance, again as a product of small independent merchants.

He sees a tension in the modern West between, on the one hand, the potentials for autonomy and creativity and the proliferation of "open societies" and, on the other hand, the spirit - crushing force of capitalism. These are characterized as the capitalist imaginary and the creative imaginary:

I think that we are at a crossing in the roads of history, history in the grand sense. One road already appears clearly laid out, at least in its general orientation. That's the road of the loss of meaning, of the repetition of empty forms, of conformism, apathy, irresponsibility and cynicism at the same time as it is that of the tightening grip of the capitalist imaginary of unlimited expansion of "rational mastery," pseudorational pseudomastery, of an unlimited expansion of consumption for the sake of consumption, that is to say, for nothing, and of a technoscience that has become autonomized along its path and that is evidently involved in the domination of this capitalist imaginary. The other road should be opened: it is not at all laid out. It can be opened only through a social and political awakening, a resurgence of the project of individual and collective autonomy, that is to say, of the will to freedom. This would require an awakening of the imagination and of the creative imaginary.

He argues that, in the last two centuries, ideas about autonomy again come to the fore: "This extraordinary profusion reaches a sort of pinnacle during the two centuries stretching between 1750 and 1950. This is a very specific period because of the very great density of cultural creation but also because of its very strong subversiveness."

Castoriadis has influenced European (especially continental) thought in important ways. His interventions in sociological and political theory have resulted in some of the best known writing to emerge from the continent (especially in the figure of Jürgen Habermas, who often can be seen to be writing against Castoriadis). Hans Joas published a number of articles in American journals in order to highlight the importance of Castoriadis' work to a North American sociological audience, and the enduring importance of Johann P. Arnason, both for his critical engagement with Castoriadis' thought, but also for his sustained efforts to introduce Castoriadis' thought to the English speaking public (especially during his editorship of the journal Thesis Eleven) must also be noted. In the last few years, there has been growing interest in Castoriadis’s thought, including the publication of two monographs authored by Arnason’s former students: Jeff Klooger’s Castoriadis: Psyche, Society, Autonomy (Brill), and Suzi Adams's Castoriadis’ Ontology: Being and Creation (Fordham University Press).