<Back to Index>

- Admiral of the Fleet of the Royal Navy Andrew Browne Cunningham, 1883

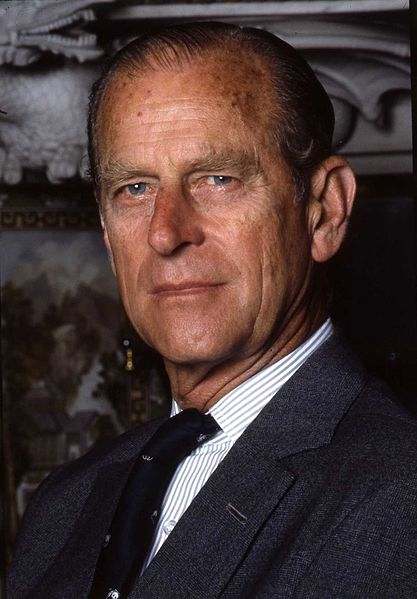

- Duke of Edinburgh Prince Philip, 1921

PAGE SPONSOR

Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Browne Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope KT, GCB, OM, DSO and two Bars (7 January 1883 – 12 June 1963), was a British admiral of the Second World War. Cunningham was widely known by his nickname, "ABC".

Cunningham was born in Rathmines in the south side of Dublin on 7 January 1883. After starting his schooling in Dublin and Edinburgh, he enrolled at Stubbington House School, at the age of ten, beginning his association with the Royal Navy. After passing out of Britannia Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, in 1898, he progressed rapidly in rank. He commanded a destroyer during the First World War and through most of the interwar period. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and two Bars, for his performance during this time, specifically for his actions in the Dardanelles and in the Baltics.

In the Second World War, as Commander - in - Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, Cunningham led British naval forces to victory in several critical Mediterranean naval battles. These included the attack on Taranto in 1940, the first completely all - aircraft naval attack in history, and the Battle of Cape Matapan in 1941. Cunningham controlled the defense of the Mediterranean supply lines through Alexandria, Gibraltar and the key chokepoint of Malta. The admiral also directed naval support for the various major allied landings in the Western Mediterranean littoral. In 1943, Cunningham was promoted to First Sea Lord, a position he held until his retirement in 1946. He was ennobled as Baron Cunningham of Hyndhope in 1945 and made Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope the following year. After his retirement Cunningham enjoyed several ceremonial positions including Lord High Steward at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. He died on 12 June 1963.

Cunningham was born at Rathmines, County Dublin, on 7 January 1883, the third of five children born to Professor Daniel Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth Cumming Browne, both of Scottish ancestry. General Sir Alan Cunningham was his younger brother. His parents were described as having a "strong intellectual and clerical tradition," both grandfathers having been in the clergy. His father was a Professor of Anatomy at Trinity College, Dublin, whilst his mother stayed at home. Elizabeth Browne, with the aid of servants and governesses, oversaw much of his upbringing; as a result he reportedly had a "warm and close" relationship with her. After a short introduction to schooling in Dublin he was sent to Edinburgh Academy, where he stayed with his aunts Doodles and Connie May. At the age of ten he received a telegram from his father asking "would you like to go into the Navy?" At the time, the family had no maritime connections, and Cunningham only had a vague interest in the sea. Nevertheless he replied "Yes, I should like to be an Admiral". He was then sent to a Naval Preparatory School, Stubbington House, which specialized in sending pupils through the Dartmouth entrance examinations. Cunningham passed the exams showing particular strength in mathematics.

Along with 64 other boys Cunningham joined the Royal Navy as a cadet aboard the training ship HMS Britannia in 1897 following preparatory education at Stubbington House School. One of his classmates was future Admiral of the Fleet James Fownes Somerville. Cunningham was known for his lack of enthusiasm for field sports, although he did enjoy golf and spent most of his spare time "messing around in boats". He said in his memoirs that by the end of his course he was "anxious to seek adventure at sea". Although he committed numerous minor misdemeanors, he still obtained a very good for conduct. He passed out tenth in April, 1898, with first - class-marks for mathematics and seamanship.

His first service was as a midshipman on HMS Doris in 1899, serving at the Cape of Good Hope Station when the Second Boer War began. By February, 1900, he had transferred into the Naval Brigade as he believed "this promised opportunities for bravery and distinction in action." Cunningham then saw action at Pretoria and Diamond Hill as part of the Naval Brigade. He then went back to sea, as midshipman in HMS Hannibal in December, 1901. The following November he joined the protected cruiser HMS Diadem. Beginning in 1902, Cunningham took Sub - Lieutenant courses at Portsmouth and Greenwich; he served as sub - lieutenant on the battleship HMS Implacable, in the Mediterranean, for six months in 1903. In September 1903, he was transferred to HMS Locust to serve as second - in - command. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1904, and served on several vessels during the next four years. In 1908, he was awarded his first command, HM Torpedo Boat No. 14.

Cunningham was a highly decorated officer during the First World War, receiving the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) and two bars. In 1911 he was given command of the destroyer HMS Scorpion, which he commanded throughout the war. In 1914, Scorpion was involved in the shadowing of the German battlecruiser and cruiser SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau. This operation was intended to find and destroy the Goeben and the Breslau but the German warships evaded the British fleet, and passed through the Dardanelles to reach Constantinople. Their arrival contributed to the Ottoman Empire joining the Central Powers in November 1914. Though a bloodless "battle", the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications — in the words of Winston Churchill, they brought "more slaughter, more misery and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."[14]

Cunningham stayed on in the Mediterranean and in 1915 Scorpion was involved in the attack on the Dardanelles. For his performance Cunningham was rewarded with promotion to commander and the award of the Distinguished Service Order. Cunningham spent much of 1916 on routine patrols. In late 1916, he was engaged in convoy protection, a duty he regarded as mundane. He had no contact with German U-boats during this time, on which he commented; "The immunity of my convoys was probably due to sheer luck". Convinced that the Mediterranean held few offensive possibilities he requested to sail for home. Scorpion paid off on 21 January 1918. In his seven years as captain of the Scorpion, Cunningham had developed a reputation for first class seamanship. He was transferred by Vice - Admiral Roger Keyes to HMS Termagent, part of Keyes' Dover Patrol, in April 1918. and for his actions with the Dover Patrol, he was awarded a bar to his DSO the following year.

Cunningham saw much action in the interwar years. In 1919, he commanded the S-class destroyer Seafire, on duty in the Baltic. The Communists, the White Russians, several varieties of Latvian nationalists, Germans and the Poles were trying to control Latvia; the British Government had recognized Latvia's independence after the Treaty of Brest - Litovsk. It was on this voyage that Cunningham first met Admiral Walter Cowan. Cunningham was impressed by Cowan's methods, specifically his navigation of the potentially dangerous seas, with thick fog and minefields threatening the fleet. Throughout several potentially problematic encounters with German forces trying to undermine the Latvian independence movement, Cunningham exhibited "good self control and judgement". Cowan was quoted as saying "Commander Cunningham has on one occasion after another acted with unfailing promptitude and decision, and has proved himself an Officer of exceptional valor and unerring resolution."

For his actions in the Baltic, Cunningham was awarded a second bar to his DSO, and promoted to captain in 1920. On his return from the Baltic in 1922, he was appointed captain of the British 6th Destroyer Flotilla. Further commands were to follow; the British 1st Destroyer Flotilla in 1923, and the destroyer base, HMS Lochinvar, at Port Edgar in the Firth of Forth, from 1927 – 1926. Cunningham renewed his association with Vice Admiral Cowan between 1926 and 1928, when Cunningham was flag captain and chief staff officer to Cowan while serving on the North America and West Indies Squadron. In his memoirs Cunningham made clear the "high regard" in which he held Cowan, and the many lessons he learned from him during their two periods of service together. The late 1920s found Cunningham back in the UK participating in courses at the Army's Senior Officers' School at Sheerness, as well as at the Imperial Defence College. While Cunningham was at the Imperial Defence College, in 1929, he married Nona Byatt (daughter of Horace Byatt, MA; the couple had no children). After a year at the College, Cunningham was given command of his first big ship; the battleship Rodney. Eighteen months later, he was appointed commodore of HMS Pembroke, the Royal Naval barracks at Chatham.

In September 1932, Cunningham was promoted to flag rank, and Aide - de - Camp to the King. He was appointed Rear Admiral (Destroyers) in the Mediterranean in December 1933 and was made a Companion of the Bath in 1934. Having hoisted his flag in the light cruiser HMS Coventry, Cunningham used his time to practice fleet handling for which he was to receive much praise in the Second World War. There were also fleet exercises in the Atlantic Ocean in which he learned the skills and values of night actions that he would also use to great effect in years to come.

On his promotion to vice admiral in July 1936, due to the interwar naval policy, further active employment seemed remote. However, a year later due to the illness of Sir Geoffrey Blake, Cunningham assumed the combined appointment of commander of the British Battlecruiser Squadron and second - in - command of the Mediterranean Fleet, with HMS Hood as his flagship. After his long service in small ships, Cunningham considered his accommodation aboard Hood to be almost palatial, even surpassing his previous big ship experience on Rodney.

He retained command until September 1938, when he was appointed to the Admiralty as Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, although he did not actually take up this post until December 1939. He accepted this shore job with reluctance since he loathed administration, but the Board of Admiralty’s high regard of him was evident. For six months during an illness of Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse, the then First Sea Lord, he deputized for Backhouse on the Committee of Imperial Defence and on the Admiralty Board. In 1939 he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), becoming known as Sir Andrew Cunningham.

Cunningham described the command of the Mediterranean Fleet as "The finest command the Royal Navy has to offer" and he remarked in his memoirs that "I probably knew the Mediterranean as well as any Naval Officer of my generation". Cunningham was made Commander - in - Chief, Mediterranean, hoisting his flag in HMS Warspite on 6 June 1939, one day after arriving in Alexandria on 5 June 1939. As Commander - in - Chief, Cunningham's main concern was for the safety of convoys heading for Egypt and Malta. These convoys were highly significant in that they were desperately needed to keep Malta, a small British colony and naval base, in the war. Malta was a strategic strong point and Cunningham fully appreciated this. Cunningham believed that the main threat to British Sea Power in the Mediterranean would come from the Italian Fleet. As such Cunningham had his fleet at a heightened state of readiness, so that when Italy did choose to enter into hostilities, then the British Fleet would be ready.

In his role as Commander - in - Chief, Mediterranean, Cunningham had to negotiate with the French Admiral Rene - Emile Godfroy for the demilitarization and internment of a French squadron at Alexandria, in June 1940, following the Fall of France. Churchill had ordered Cunningham to prevent the French warships from leaving port, and to ensure that French warships did not pass into enemy hands. Stationed at the time at Alexandria, Cunningham entered into delicate negotiations with Godfroy to ensure his fleet, which consisted of the battleship Lorraine, 4 cruisers, 3 destroyers and a submarine, posed no threat. The Admiralty ordered Cunningham to complete the negotiations on 3 July. Just as an agreement seemed imminent Godfroy heard of the British action against the French at Mers el Kebir and, for a while, Cunningham feared a battle between French and British warships in the confines of Alexandria harbor. The deadline was overrun but negotiations ended well, after Cunningham put them on a more personal level and had the British ships appeal to their French opposite numbers. Cunningham's negotiations succeeded and the French emptied their fuel bunkers and removed the firing mechanisms from their guns. Cunningham in turn promised to repatriate the ships' crews.

Although the threat from the French Fleet had been neutralized, Cunningham was still aware of the threat posed by the Italian Fleet to British North African operations, based in Egypt. Although the Royal Navy had won in several actions in the Mediterranean, considerably upsetting the balance of power, the Italians who were following the theory of a fleet in being had left their ships in harbor. This made the threat of a sortie against the British Fleet a serious problem. At the time the harbor at Taranto contained six battleships (five of them battle worthy), seven heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and eight destroyers. The Admiralty, concerned with the potential for an attack, had drawn up Operation Judgement; a surprise attack on Taranto Harbor. To carry out the attack, the Admiralty sent the new aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, commanded by Lumley Lyster, to join HMS Eagle in Cunningham's fleet.

The attack started at 21:00, 11 November 1940, when the first of two waves of Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers took off from Illustrious, followed by the second wave an hour later. The attack was a great success: the Italian fleet lost half its strength in one night. The "fleet - in - being" diminished in importance and the threat to the Royal Navy's control of the Mediterranean had been considerably reduced. Cunningham said of the victory: "Taranto, and the night of 11 – 12 November 1940, should be remembered for ever as having shown once and for all that in the Fleet Air Arm the Navy has its most devastating weapon." The Royal Navy had launched the first all - aircraft naval attack in history, flying a small number of aircraft from an aircraft carrier. This, and other aspects of the raid, were important facts in the planning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941: the Japanese planning staff were thought to have studied it intensively.

Cunningham's official reaction at the time was memorably terse. After landing the last of the attacking aircraft, Illustrious signaled "Operation Judgement executed". After seeing aerial reconnaissance photographs the next day which showed several Italian ships sunk or out of action, Cunningham replied with the two - letter code group which signified, "Maneuver well executed".

At the end of March 1941, Hitler wanted the convoys supplying the British Expeditionary force in Greece stopped, and the Italian Navy was the only force able to attempt this. Cunningham stated in his biography: "I myself was inclined to think that the Italians would not try anything. I bet Commander Power, the Staff Officer, Operations, the sum of ten shillings that we would see nothing of the enemy." Under pressure from Germany, the Italian Fleet planned to launch an attack on the British Fleet on 28 March 1941.

The Italian commander, Admiral Angelo Iachino, intended to carry out a surprise attack on the British Cruiser Squadron in the area (commanded by Vice - Admiral Sir Henry Pridham - Wippell), executing a pincer movement with the battleship Vittorio Veneto. Cunningham though, was aware of Italian naval activity through intercepts of Italian Enigma messages. Although Italian intentions were unclear, Cunningham's staff believed an attack upon British troop convoys was likely and orders were issued to spoil the enemy plan and, if possible, intercept their fleet. Cunningham wished, however, to disguise his own activity and arranged for a game of golf and a fictitious evening gathering to mislead enemy agents (he was, in fact, overheard by the local Japanese Consul). After sunset, he boarded HMS Warspite and left Alexandria.

Cunningham, realizing that an air attack could weaken the Italians, ordered an attack by the Formidable's Albacore torpedo bombers. A hit on the Vittorio Veneto slowed her temporarily and Iachino, realizing his fleet was vulnerable without air cover, ordered his forces to retire. Cunningham gave the order to pursue the Italian Fleet.

An air attack from the Formidable had disabled the cruiser Pola and Iachino, unaware of Cunningham's pursuing battlefleet, ordered a squadron of cruisers and destroyers to return and protect the Pola. Cunningham, meanwhile, was joining up with Pridham - Wippell's cruiser squadron. Throughout the day several chases and sorties occurred with no overall victor. None of the Italian ships were equipped for night fighting, and when night fell, they made to return to Taranto. The British battlefleet equipped with radar detected the Italians shortly after 22:00. In a pivotal moment in naval warfare during the Second World War, the battleships Barham, Valiant and Warspite opened fire on two Italian cruisers at only 3,800 yards (3.5 km), destroying them in only five minutes.

Although the Vittorio Veneto escaped from the battle by returning to Taranto, there were many accolades given to Cunningham for continuing the pursuit at night, against the advice of his staff. After the previous defeat at Taranto, the defeat at Cape Matapan dealt another strategic blow to the Italian Navy. Five ships - three heavy cruisers and two destroyers - were sunk, and around 2,400 Italian sailors were killed, missing or captured. The British lost only three aircrew when one torpedo bomber was shot down. Cunningham had lost his bet with Commander Power but he had won a strategic victory in the war in the Mediterranean. The defeats at Taranto and Cape Matapan meant that the Italian Navy did not intervene in the heavily contested evacuations of Greece and Crete, later in 1941. It also ensured that, for the remainder of the war, the Regia Marina conceded the Eastern Mediterranean to the Allied Fleet, and did not leave port for the remainder of the war.

On the morning of 20 May 1941, Nazi Germany launched an airborne invasion of Crete, under the code name Unternehmen Merkur (Operation Mercury). Despite initial heavy casualties, Maleme airfield in western Crete fell to the Germans and enabled the Germans to fly in heavy reinforcements and overwhelm the Allied forces.

After a week of heavy fighting, British commanders decided that the situation was hopeless and ordered a withdrawal from Sfakia. During the next four nights, 16,000 troops were evacuated to Egypt by ships (including HMS Ajax of Battle of the River Plate fame). A smaller number of ships were to withdraw troops on a separate mission from Heraklion, but these ships were attacked en route by Luftwaffe dive bombers. Without air cover, Cunningham's ships suffered serious losses. Cunningham was determined, though, that the "navy must not let the army down", and when army generals feared he would lose too many ships, Cunningham famously said,

| “ | It takes three years to build a ship; it takes three centuries to build a tradition. | ” |

The "never say die" attitude of Cunningham and the men under his command meant that of 22,000 men on Crete, 16,500 were rescued but at the loss of three cruisers and six destroyers. Fifteen other major warships were damaged.

Cunningham became a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (GCB), "in recognition of the recent successful combined operations in the Middle East", in March 1941 and was created a baronet, of Bishop's Waltham in the County of Southampton, in July 1942. From late 1942 to early 1943, he served under General Eisenhower, who made him the Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. In this role Cunningham commanded the large fleet that covered the Anglo - American landings in North Africa (Operation Torch). General Eisenhower said of him in his diary:

| “ | Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham. He remains in my opinion at the top of my subordinates in absolute selflessness, energy, devotion to duty, knowledge of his task, and in understanding of the requirements of allied operations. My opinions as to his superior qualifications have never wavered for a second. | ” |

On 21 January 1943, Cunningham was promoted to admiral of the fleet. February 1943 saw him return to his post as Commander - in - Chief, Mediterranean Fleet. Three months later, when Axis forces in North Africa were on the verge of surrender, he ordered that none should be allowed to escape. Entirely in keeping with his fiery character he signaled the fleet "Sink, burn and destroy: Let nothing pass". He oversaw the naval forces used in the joint Anglo - American amphibious invasions of Sicily, during Operation Husky, Operation Baytown and Operation Avalanche. On the morning of 11 September 1943, Cunningham was present at Malta when the Italian Fleet surrendered. Cunningham informed the Admiralty with a telegram; "Please to inform your Lordships that the Italian battle fleet now lies at anchor under the guns of the fortress of Malta."

In October 1943, Cunningham became First Sea Lord of the Admiralty and Chief of the Naval Staff, after the death of Dudley Pound. This promotion meant that he had to relinquish his coveted post of Commander - in - Chief, Mediterranean, recommending his namesake Admiral John H.D. Cunningham as his successor. In the position of First Sea Lord, and as a member of the Chiefs of Staff committee, Cunningham was responsible for the overall strategic direction of the navy for the remainder of the war. He attended the major conferences at Cairo, Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam, at which the Allies discussed future strategy, including the invasion of Normandy and the deployment of a British fleet to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1945 Cunningham was appointed a Knight of the Thistle and raised to the peerage as "Baron Cunningham of Hyndhope", of Kirkhope in the County of Selkirk. He was entitled to retire at the end of the war in 1945 but he resolved to pilot the Navy through the transition to peace before retiring. With the election of Clement Attlee as British Prime Minister in 1945, and the implementation of his Post - war consensus, there was a large reduction in the Defense Budget. The extensive reorganization was a challenge for Cunningham. "We very soon came to realize how much easier it was to make war than to reorganize for peace." Due to pressures on the budget from all three services, the Navy embarked on a reduction program that was larger than Cunningham had envisaged.

He was made "Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope", of Kirkhope in the County of Selkirk, in January 1946, and appointed to the Order of Merit in June of that year. At the end of May 1946, after overseeing the transition through to peacetime, Cunningham retired from his post as First Sea Lord. Cunningham retreated to the "little house in the country", 'Palace House', at Bishop's Waltham in Hampshire, which he and Lady Cunningham had acquired before the war. They both had a busy retirement. He attended the House of Lords irregularly and occasionally lent his name to press statements about the Royal Navy, particularly those relating to Admiral Dudley North, who had been relieved of his command of Gibraltar in 1940. Cunningham, and several of the surviving admirals of the fleet, set about securing justice for North, and they succeeded with a partial vindication in 1957. He also busied himself with various appointments; he was Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1950 and 1952, and in 1953 he acted as Lord High Steward at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Throughout this time Cunningham and his wife entertained family and friends, including his own great nephew, Jock Slater, in their extensive gardens. Cunningham died in London on 12 June 1963, and was buried at sea off Portsmouth. There were no children from his marriage and his titles consequently became extinct on his death.

A bust of Cunningham by Franta Belsky was unveiled in Trafalgar Square in London on 2 April 1967 by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. The April 2010 UK naval operation to ship British military personnel and air passengers stranded in continental Europe by the air travel disruption after the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption back to the UK was named Operation Cunningham after him.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark 10 June 1921 - 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. He was the United Kingdom's longest serving consort and the oldest serving spouse of a reigning British monarch.

A member of the Danish - German House of Schleswig - Holstein - Sonderburg - Glücksburg and a great - great - grandson of Queen Victoria, Prince Philip was born in Greece into the Greek Royal Family, but his family was exiled from Greece when he was a child. After being educated in Germany, England and Scotland, he joined the British Royal Navy at the age of 18 in 1939. From July 1939, he began corresponding with the 13 year old Princess Elizabeth (his second cousin once removed and the eldest daughter and heiress presumptive of King George VI) whom he had first met in 1934. During World War II he served with the Mediterranean and Pacific fleets.

After the war, Philip was granted permission by George VI to marry Elizabeth. Prior to the official engagement announcement, he abandoned his Greek and Danish royal titles, converted from Greek Orthodoxy to Anglicanism, and became a naturalized British subject, adopting the surname Mountbatten from his maternal grandparents. After an official engagement of five months, as Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, he married Elizabeth on 20 November 1947. On his marriage, he was granted the style of His Royal Highness and the title of Duke of Edinburgh by the King, his father - in - law. Philip left active service, having reached the rank of Commander, when Elizabeth became queen in 1952. The Queen, his wife, made him a Prince of the United Kingdom in 1957.

Philip had four children with Elizabeth: Prince Charles, Princess Anne, Prince Andrew and Prince Edward. Through an Order in Council issued in 1960, descendants of Philip and Elizabeth not bearing royal styles and titles can use the surname Mountbatten - Windsor, which has also been used by some members who do hold titles, such as Charles and Anne.

A keen sportsman, Philip helped develop the equestrian event of carriage driving. He was a patron of over 800 organizations, and chairman of The Duke of Edinburgh's Award Scheme for people aged 14 to 24 years.

Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark was born at Mon Repos on the Greek island of Corfu on 10 June 1921, the only son and fifth and final child of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark and Princess Alice of Battenberg. Philip's four elder sisters were Margarita, Theodora, Cecilie, and Sophie. He was baptized into the Greek Orthodox Church. His godparents were Queen Olga of Greece (his paternal grandmother) and the Mayor of Corfu.

Shortly after Philip's birth, his maternal grandfather, Prince Louis of Battenberg, died in London. Louis was a naturalized British citizen and, after long and distinguished service in the Royal Navy, had renounced his German titles and adopted the surname Mountbatten. After visiting London for the memorial, Philip and his mother returned to Greece where Prince Andrew had remained behind to command an army division embroiled in the Greco - Turkish War (1919 – 1922).

The war went badly for Greece, and the Turks made large gains. On 22 September 1922, Philip's uncle, the reigning King Constantine I of Greece, was forced to abdicate, and Prince Andrew, along with others, was arrested by the military government. The commander of the army, General Georgios Hatzianestis, and five senior politicians were executed. Prince Andrew's life was believed to be in danger, and Alice was under surveillance. In December, a revolutionary court banished Prince Andrew from Greece for life. The British naval vessel HMS Calypso evacuated Prince Andrew's family, with Philip being carried to safety in a cot made from a fruit box. Philip's family went to France, where they settled in the Paris suburb of Saint - Cloud in a house lent to them by his aunt, Princess George of Greece.

Although both he and his father were born in Greece, he left the country as a baby and does not have a strong grasp of Greek. In 1992, Philip said that he "could understand a certain amount of" the language. He speaks fluent English, German and French.Philip was first educated at an American school in Paris run by Donald MacJannet, who described Philip as a "rugged, boisterous ... but always remarkably polite" boy. In 1928, he was sent to the UK to attend Cheam School, living with his maternal grandmother at Kensington Palace and his uncle, George Mountbatten, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven, at Lynden Manor in Bray, Berkshire. In the next three years, his four sisters married German noblemen and moved to Germany, his mother was placed in an asylum after being diagnosed with schizophrenia, and his father moved to a small flat in Monte Carlo. Philip had little contact with his mother for the remainder of his childhood. In 1933, he was sent to Schule Schloss Salem in Germany, which had the "advantage of saving school fees" because it was owned by the family of his brother - in - law, Berthold, Margrave of Baden. With the rise of Nazism in Germany, Salem's Jewish founder, Kurt Hahn, fled persecution and founded Gordonstoun School in Scotland. After two terms at Salem, Philip moved to Gordonstoun. In 1937, his sister Cecilie, her husband (Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse), her two young sons and her mother - in - law were killed in an air crash at Ostend; Philip, then sixteen years old, attended the funeral in Darmstadt. The following year, his uncle and guardian Lord Milford Haven died of bone cancer.

After leaving Gordonstoun in 1939, Prince Philip joined the Royal Navy, graduating the next year from the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, as the top cadet in his course. He was commissioned as a midshipman in January 1940. Philip spent four months on the battleship HMS Ramillies, protecting convoys of the Australian Expeditionary Force in the Indian Ocean, followed by shorter postings on HM Ships Kent, Shropshire and in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). After the invasion of Greece by Italy in October 1940, he was transferred from the Indian Ocean to the battleship HMS Valiant in the Mediterranean Fleet. Among other engagements, he was involved in the Battle of Crete, was mentioned in dispatches for his service during the Battle of Cape Matapan where he controlled the battleship's searchlights.

Philip was also awarded the Greek War Cross of Valor. Duties of lesser glory included stoking the boilers of the troop transport ship RMS Empress of Russia. He was promoted to sub - lieutenant after a series of courses at Portsmouth in which he gained the top grade in four out of five sections of the qualifying examination. In June 1942, he was appointed to the V and W class destroyer and flotilla leader, HMS Wallace, which was involved in convoy escort tasks on the east coast of Britain, as well as the allied invasion of Sicily. Promotion to lieutenant followed on 16 July 1942. In October of the same year he became first lieutenant of HMS Wallace, at 21 years old one of the youngest first lieutenants in the Royal Navy. During the invasion of Sicily, in July 1943, as second in command of HMS Wallace, he saved his ship from a night bomber attack. He devised a plan to launch a raft with smoke floats that successfully distracted the bombers allowing the ship to slip away unnoticed. In 1944, he moved on to the new destroyer, HMS Whelp, where he saw service with the British Pacific Fleet in the 27th Destroyer Flotilla. He was present in Tokyo Bay when the instrument of Japanese surrender was signed. In January 1946, Philip returned to the United Kingdom on the Whelp, and was posted as an instructor at HMS Royal Arthur, the Petty Officers' School in Corsham, Wiltshire.

In 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth toured the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. During the visit, the Queen and Earl Mountbatten asked Philip to escort the King's two daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret, who were Philip's third cousins through Queen Victoria, and second cousins once removed through King Christian IX of Denmark. Elizabeth fell in love with Philip and they began to exchange letters. Eventually, in the summer of 1946, Philip asked the King for his daughter's hand in marriage. The King granted his request, provided that any formal engagement was delayed until Elizabeth's twenty - first birthday the following April. By March 1947, Philip had abandoned his Greek and Danish royal titles, had adopted the surname Mountbatten from his mother's family, and had become a naturalized British subject. The engagement was announced to the public on 10 July 1947. The day preceding his wedding, King George VI bestowed the style His Royal Highness on Philip, and on the morning of the wedding, 20 November 1947, he was made the Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth, and Baron Greenwich of Greenwich in the County of London.

Philip and Elizabeth were married in a ceremony at Westminster Abbey, recorded and broadcast by BBC radio to 200 million people around the world. However, in post - war Britain, it was not acceptable for any of the Duke of Edinburgh's German relations to be invited to the wedding, including Philip's three surviving sisters, all of whom had married German princes, some of them with Nazi connections. After their marriage, the Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh took up residence at Clarence House. Their first two children were born: Prince Charles in 1948 and Princess Anne in 1950.

Philip was keen to pursue his naval career, though aware that his wife's future role as queen would eventually eclipse his ambitions. Nevertheless, Philip returned to the navy after his honeymoon, at first in a desk job at the Admiralty, and later on a staff course at the Naval Staff College, Greenwich. From 1949, he was stationed in Malta, after being posted as the first lieutenant of the destroyer HMS Chequers, the lead ship of the 1st Destroyer Flotilla in the Mediterranean Fleet. In July 1950, he was promoted to lieutenant commander and given command of the frigate HMS Magpie. He was promoted to commander in 1952, but his active naval career ended in July 1951. In 1960 he joined The Castaways' Club, having been introduced by his first cousin David Mountbatten, 3rd Marquess of Milford Haven, which enabled him to keep in close contact with many of his naval contemporaries.

With the King in ill health, Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh were each appointed to the Privy Council on 4 November 1951, after having made a coast - to - coast tour of Canada. At the end of January the following year, Philip and his wife set out on a tour of the Commonwealth. On 6 February 1952, when they were in Kenya, Elizabeth's father died so she became Queen. It was Philip who broke the news of her father's death to Elizabeth at Sagana Lodge, and the royal party immediately returned to the United Kingdom.

The accession of Elizabeth to the throne brought up the question of the name of the royal house. The Duke's uncle, Louis Mountbatten, advocated the name House of Mountbatten, as Elizabeth would typically have taken Philip's last name on marriage; however, when Queen Mary, Elizabeth's paternal grandmother, heard of this suggestion, she informed the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who himself later advised the Queen to issue a royal proclamation declaring that the royal house was to remain known as the House of Windsor. The Duke privately complained, "I am nothing but a bloody amoeba. I am the only man in the country not allowed to give his name to his own children."

In 1960, several years after the death of Queen Mary and the resignation of Churchill, the Queen issued an Order in Council declaring that the surname of male line descendants of the Duke and the Queen who are not styled as Royal Highness, or titled as Prince or Princess, was to be Mountbatten - Windsor. In practice, the Duke's children have all used Mountbatten - Windsor as a surname when not using a name derived from their highest titles (i.e., Wales, York, or Wessex); similarly, his male line grandchildren use names derived from these titles.

After her accession to the throne, the Queen also announced that the Duke was to have "place, pre-eminence and precedence" next to her "on all occasions and in all meetings, except where otherwise provided by Act of Parliament". This meant the Duke took precedence over his son, the Prince of Wales, except, officially, in the British parliament. In fact, however, he attended Parliament only when escorting the Queen for the annual State Opening of Parliament, where he walked and sat beside her.

As consort to the Queen, Philip supported his wife in her new duties as Sovereign, accompanying her to ceremonies such as the State Opening of Parliament in various countries, state dinners, and tours abroad. As Chairman of the Coronation Commission, he was the first member of the royal family to fly in a helicopter, visiting the troops that were to take part in the ceremony. Philip was not crowned in the service, but knelt before Elizabeth, with her hands enclosing his, and swore to be her "liege man of life and limb".

In the early 1950s, his sister - in - law, Princess Margaret, considered marrying a divorced older man, Peter Townsend. The press accused Philip of being hostile to the match. "I haven't done anything," he complained. Philip had not interfered, preferring to stay out of other people's love lives. Eventually, Margaret and Townsend parted. For six months over 1953 – 54 Philip and Elizabeth toured the Commonwealth; again their children were left in the United Kingdom.

In 1956, the Duke founded the Duke of Edinburgh's Award with Kurt Hahn, in order to give young people "a sense of responsibility to themselves and their communities". From 1956 to 1957, Philip traveled around the world aboard the newly commissioned HMY Britannia, during which he opened the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne and visited the Antarctic. The Queen and the children remained in the UK. On the return leg of the journey, Philip's private secretary, Mike Parker, was sued for divorce by his wife. As with Townsend, the press still portrayed divorce as a scandal, and eventually Parker resigned. He later said that the Duke was very supportive and "the Queen was wonderful throughout. She regarded divorce as a sadness, not a hanging offense." In a show of public support, the Queen created Parker a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order.

Further press reports claimed that the Queen and the Duke were drifting apart, which enraged the Duke and dismayed the Queen, who issued a strongly worded denial. On 22 February 1957, she granted her husband the style and title of a Prince of the United Kingdom by Letters Patent, restoring the princely status that he had formally renounced ten years earlier. On the same date, it was gazetted that he was to be known as "His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh".

Philip was appointed to the Queen's Privy Council for Canada on 14 October 1957, taking his Oath of Allegiance before the Queen in person at her Canadian residence, Rideau Hall. Visiting Canada in 1969, Philip spoke about his views on republicanism:

"It is a complete misconception to imagine that the monarchy exists in the interests of the monarch. It doesn't. It exists in the interests of the people. If at any time any nation decides that the system is unacceptable, then it is up to them to change it."

Philip was patron of some 800 organizations, particularly focused on the environment, industry, sport and education. He served as UK President of the World Wildlife Fund from 1961 to 1982, International President from 1981 and President Emeritus from 1996. He was patron of The Work Foundation, was President of the International Equestrian Federation from 1964 to 1986, and served as Chancellor of the Universities of Cambridge, Edinburgh, Salford and Wales.

At the beginning of 1981, Philip wrote to his eldest son, Charles, counseling him to make up his mind to either propose to Lady Diana Spencer, or break off their courtship. Charles felt pressured by his father to make a decision, and did so, proposing to Diana in February. They married six months later.

By 1992, the marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales had broken down. The Queen and Philip hosted a meeting between Charles and Diana, trying to get them reconciled but without success. Philip wrote to Diana, expressing his disappointment at both Charles's and her extra - marital affairs, and asking her to examine both his and her behavior from the other's point of view. The Duke was direct, and Diana was sensitive. She found the letters hard to take, but she nevertheless appreciated that he was acting with good intent. Charles and Diana separated and later divorced.

A year after the divorce, Diana was killed in a car crash in Paris on 31 August 1997. At the time, the Duke was on holiday at Balmoral with the extended royal family. In their grief, Diana's two sons, Princes William and Harry, wanted to attend church, and so their grandparents took them that morning. For five days, the Queen and the Duke shielded their grandsons from the ensuing press interest by keeping them at Balmoral where they could grieve in private. The Royal Family's seclusion caused public dismay, but the public mood was transformed from hostility to respect by a live broadcast made by the Queen on 5 September. Uncertain as to whether they should walk behind her coffin during the funeral procession, Diana's sons hesitated. Philip told William, "If you don't walk, I think you'll regret it later. If I walk, will you walk with me?" On the day of the funeral, Philip, William, Harry, Charles and Diana's brother, Earl Spencer, walked through London behind her bier.

Over the next few years Mohammed Al-Fayed, whose son Dodi Fayed was also killed in the crash, claimed that Prince Philip had ordered the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, and that the accident was staged. The inquest into Diana's death concluded in 2008 that there was no evidence of a conspiracy.

During the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II in 2002, the Duke was commended by the Speaker of the British House of Commons for his role in supporting the Queen during her reign. The Duke of Edinburgh's time as royal consort exceeded that of any other consort in British history; however, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother (his mother - in - law), who died aged 101, was the consort with the longest lifespan.

In April 2008, Philip was admitted to the King Edward VII Hospital for "assessment and treatment" for a chest infection, though he walked into the hospital unaided and recovered quickly, and was discharged three days later to recuperate at Windsor Castle. In August the same year, the Evening Standard newspaper reported that Philip was suffering from prostate cancer. Buckingham Palace, which usually refuses to comment on rumors of ill health, claimed that the report was an invasion of privacy. Unusually, Philip authorized a statement denying the story. The newspaper retracted the report, and admitted it was untrue.

In June 2011, in an interview marking the occasion of his 90th birthday he said that he would now slow down and reduce his duties, stating that he had "done [his] bit". While staying at the royal residence at Sandringham, Norfolk, on 23 December 2011, the Duke suffered chest pains and was taken to the cardio - thoracic unit at Papworth Hospital, Cambridgeshire, where he underwent successful coronary angioplasty and stenting. He was discharged on 27 December.

On 4 June 2012, during the celebrations in honor of his wife's Diamond Jubilee, Philip was taken from Windsor Castle to the King Edward VII Hospital, London suffering from a bladder infection. He was released from hospital on 9 June.

Prince Philip holds the record for the longest lived male member of the British Royal Familyand for the longest lived male descendant of Queen Victoria.

Philip played polo until 1971, when he started to compete in carriage driving, a sport which he helped expand; the early rule book was drafted under his supervision. He was a keen yachtsman, striking up a friendship in 1949 with Uffa Fox in Cowes. He and the Queen regularly attended Cowes Week in HMY Britannia. His first airborne flying lesson took place in 1952; by his 70th birthday he had accrued 5,150 pilot hours. He has painted with oils, and collected artworks, including contemporary cartoons, which hang at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, Sandringham House and Balmoral Castle. Hugh Casson described Philip's own artwork as "exactly what you'd expect ... totally direct, no hanging about. Strong colors, vigorous brushstrokes."

In 1979, when Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip were guests of President Carter, Prince Philip was approached by White House butler Lynwood Westray and another unnamed butler:

"Your majesty, would you like a cordial?" Westray asked him. "I'll take one if you'll let me serve you," Prince Philip responded. "Oh my God, this had never happened before," said Westray. "There we were standing there. I was holding the glasses and my buddy was holding the liqueurs and we looked at each other, and I said 'If that's the only way you'll have it, we'll go along with it.' And the prince served us what he was having, and the three of us had a drink and a conversation. It was an honor to let him do it."

Over his sixty years as royal consort, Philip became famous for making remarks that were often construed as being offensive or stereotypical in nature. Some of them were immediately interpreted as gaffes; but other awkward observations were construed by apologists as merely odd, off - color, and often funny. In his own words, comments attributed to Prince Philip have contributed to the perception that he is "a cantankerous old sod". The historian David Starkey described him as a kind of " H.R.H Victor Meldrew". For example, in May 1999 British newspapers accused Philip of insulting deaf children at a pop concert in Wales by saying, "No wonder you are deaf listening to this row." Later Philip wrote, "The story is largely invention. It so happens that my mother was quite seriously deaf and I have been Patron of the Royal National Institute for the Deaf for ages, so it's hardly likely that I would do any such thing." During a state visit to the People's Republic of China in 1986, in a private conversation with British students from Xian's North West University, Philip joked, "If you stay here much longer, you'll go slit - eyed." The British press reported on the remark as indicative of racial intolerance, but the Chinese authorities were reportedly unconcerned. Chinese students studying in the UK, an official explained, were often told in jest not to stay away too long, lest they go "round - eyed". His comment had no effect on Sino - British relations, but it shaped his own reputation.

Philip held a number of titles throughout his life. Originally holding the title and style of a prince of Greece and Denmark, Philip abandoned these royal titles before his marriage, and was thereafter created a British duke, among other noble titles. It was not, however, until the Queen issued Letters Patent in 1957 that Philip was again titled as a prince.

When addressing the Duke of Edinburgh, as with any member of the royal family except the monarch, the rules of etiquette were to address him the first time as Your Royal Highness, and thereafter as Sir.

Upon his wife's accession to the throne in 1952, the Duke of Edinburgh was appointed Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel - in - Chief of the British Army Cadet Force, and Air Commodore - in - Chief of the Air Training Corps. The following year, he was appointed to the equivalent positions in Canada, and made Admiral of the Fleet, Field Marshal, and Marshal of the Royal Air Force in the United Kingdom. Subsequent military appointments were made throughout the Commonwealth. To celebrate his 90th birthday, the Queen appointed him Lord High Admiral of the Royal Navy (the highest rank in the organization anyone other than the sovereign can hold) and to the highest ranks available in each branch of the Canadian Forces: honorary Admiral of the Maritime Command (now the Royal Canadian Navy) and General of the Land Force Command (now the Canadian Army) and Air Command (now the Royal Canadian Air Force).

Before he became consort, the Duke was appointed to the Order of the Garter on 19 November 1947. Since then, Philip received 17 different appointments and decorations in the Commonwealth, and 48 by foreign states. The inhabitants of some small villages in Vanuatu also worship Prince Philip as a god; the islanders possess portraits of the Duke and hold feasts on his birthday.

Philip was the oldest living great - great grandchild of Queen Victoria, as well as her oldest living descendant following the death of Count Carl Johan Bernadotte of Wisborg in May 2012. As such, he was in the line of succession to the thrones of 16 countries.

In July 1993, through mitochondrial DNA

analysis of a sample of Prince Philip's blood, British scientists were

able to confirm the identity of the remains of several members of Empress Alexandra of Russia's

family, several decades after their 1918 massacre by the Bolsheviks.

Prince Philip was then one of two living great - grandchildren in the female line of Alexandra's mother Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, the other being his sister Sophie, who died in 2001.