<Back to Index>

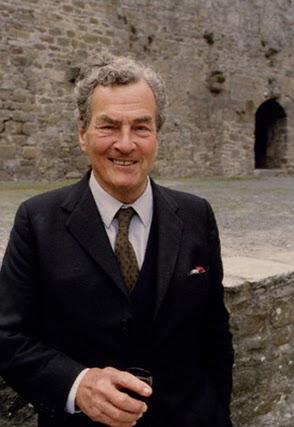

- Archaeologist and Intelligence Officer John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury, 1904

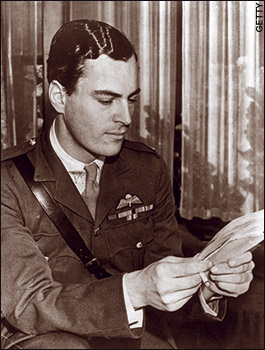

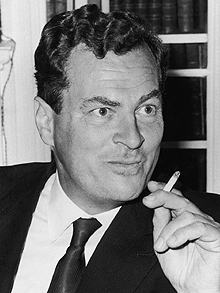

- Writer and Resistance Fighter Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor, 1915

PAGE SPONSOR

John Devitt Stringfellow Pendlebury (12 October 1904 – 22 May 1941) was a British archaeologist who worked for British intelligence during World War II. He was killed during the Battle of Crete.

John Pendlebury was born in London, the eldest son of Herbert S Pendlebury, a London surgeon, and Lilian D Devitt, a daughter of Thomas Devitt, part owner of Devitt and Moore, a shipping company. At the age of about two, he lost an eye in an accident of unknown nature while in the care of a friend of his parents, who were away for a few days. On their return conflicting reports of the accident were given. The eye could not be successfully treated. He used a prosthetic glass eye, which, it has been said by people who knew him, was generally mistaken for a real one. Throughout his life he remained determined to out - perform persons with two eyes. As a child he was taken to see Wallis Budge at the British Museum. During the conversation he apparently resolved to become an Egyptian archaeologist. Budge told him to study Classics before making up his mind. His mother died when he was 17, leaving him a legacy from his grandfather that made him financially independent. His father remarried, but had no further children. Pendlebury got along well with his stepmother and her son, Robin. He remained the center of his father's affections, whom he called "daddy" in letters.

He was educated at Winchester (1918 - 1923), before winning scholarships at Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he was awarded a Second in Part I and a First in Part II of the Classical Tripos, "with distinction in archaeology." Despite his disability, he also shone as a sportsman, with an athletics blue and competing internationally as a high jumper.

During the Easter holidays of 1923 at Winchester, Pendlebury and a master from Winchester had traveled to Greece, Pendlebury for the first time; visiting the excavations at Mycenae, they conversed with Alan Wace, then Director of the British School at Athens. Wace remembered him as a boy who wished "to see things for himself." The visit solidified his determination to become an archaeologist.

On leaving university in 1927 Pendlebury won the Cambridge University Studentship to the British School at Athens. Unable to decide between Egyptian and Greek archaeology, he decided to do both and study Egyptian artifacts found in Greece. This study resulted in his Catalogue of Egyptian objects in the Aegean area, published in 1930.

In Athens, Pendlebury stayed at the British School Student's Hostel, which was not only for students. It also provided lodging for visiting scholars doing research in Greece. They dined with the students in the same room, conversing with them and each other on scholarly topics. Pendlebury wrote his first impressions to his father, that they were so learned, "It makes me feel such an imposter being there at all." He soon found the companionship more to his liking. He hiked the Greek countryside with Sylvia Benton, who had excavated in Ithaca, competing with her to see who could walk the fastest, and became friends with Pierson Dixon, later British ambassador to France, then an archaeology student. He struck up a friendship also with another archaeology student, Hilda White, 13 years older than he and several inches shorter. Exploring the Athenian acropolis with her, he climbed over the parapet and announced to the guard "I am a Persian."

The students explored Greece in groups, living an athletic life, in contrast to the sedentary preferences of the scholars. John discovered 10 miles of an ancient road at Mycenae, where he also attended a village dance by bonfire. Systematically the students visited most of Greece. Pendlebury also found time to play tennis and hockey, and to form an athletic team for running and jumping. He first visited Crete in 1928 with the other students. After a rough sea crossing at night they hastened on to Knossos, which John at first concluded was "spoilt" by the restorations. The students then toured eastern Crete by automobile over muddy dirt roads, in frequent heavy rain and snow. At the eastern end they attempted to reach Mochlos and Pseira by leaking boat, but failed. They were prepared to swim for it. John wrote a poem about the fleas he encountered while lodging in Sitia.

It was the wrong time of year for visiting Crete. Resuming a busy life in Athens, John was invited to his first excavation by the Assistant Director of the school, Walter Heurtley, at an ancient Macedonian site in Salonica. Hilda was invited also. She became his constant companion by preference. Unknown to Pendlebury, a close connection had always existed between the British School and Sir Arthur Evans. Evans apparently heard of Pendlebury's activities in Crete and Macedonia. Later in the year, in more propitious weather, Pendlebury was invited to stay at the Villa Ariadne with Evans and Duncan Mackenzie. Hilda stayed in Heraklion. She reported that Mackenzie confided to Pendlebury in having "my own idea," which he did not tell to Evans.

By the end of the visit Evans was suggesting that Pendlebury might excavate in southern Crete, or even at Knossos. For a time Pendlebury became preoccupied with his marriage to Hilda. His family was at first opposed to the match on the basis of the age difference. After Pendlebury wrote that they could not live without each other, the wedding was approved, after an acquaintance of one year. For a honeymoon the couple undertook a physically arduous exploration of the mountainous northern Peloponnesus.

In the winter of 1928 - 1929 the Pendleburys visited Egypt for the first time. They assisted briefly in the excavation at Armant, then, late in 1928, at Tel el-Amarna. Excavations at Amarna had been started 40 years earlier by Flinders Petrie, but were then continuing under directorship of Hans Frankfort for the Egypt Exploration Society. Hans and his wife, Yettie, had been students at the British School before Pendlebury's arrival there. They were friends of Humfrey Payne, whose wife, Dilys, would become Pendlebury's biographer in the latter part of her life. Humfrey was appointed Director of the British School in 1929, still in his 20's.

John's studentship ended at the end of 1928; however, it was replaced by the MacMillen Studentship for another year's study, but only in Greece. The Pendleburys missed the subsequent winter at Amarna. In 1930 Payne and Dilys traveled to Crete to survey Eleutherina prior to its excavation, inviting the Pendleburys to accompany them. Humfrey and Dilys stayed in the Villa Ariadne, where Evans, MacKenzie and Gilliéron, Evans' fresco restorer, were at work, while John and Hilda joined Piet de Jong, Evans' artist, at the nearby Taverna. Knossos had been donated to the British School in 1924, but Evans retained control for the time being, continuing the restorations, and bringing affairs there to a conclusion. The donation had not only disposed of the estate, insuring its continuity, but gave Evans virtual control of the British School as well. One matter requiring disposition was the retirement of his Director of Excavation, Duncan MacKenzie, now past 65 and in very poor health due to alcoholism, malaria and the effects of a career of physically demanding work at Knossos. He was in fact non - functional. His retirement was set for the end of 1929, but John Pendlebury represented an opportunity Evans could not neglect.

Pendlebury was looking for a position to begin when his studentship ran out. Someone at Knossos suggested he apply for permission to excavate in Crete. Later back in Athens his father recommended he return home and apply for a lectureship. He wrote back rejecting the plan, stating that he did not want "an academic life." Shortly afterward an unsigned, confidential telegram arrived asking, if Duncan should retire in the autumn of 1929, would he be interested in the Directorship of Knossos? The telegram could only have come from Evans or Payne. Guessing Evans correctly, Pendlebury cabled back, "answer affirmative." There is no evidence that he was party to, or even knew about, the events of that autumn. Evans claimed that he had found MacKenzie sleeping during working hours, and that he was drunk. Retirement was to become effective immediately. Piet de Jong opposed this move, claiming Duncan did not drink. The truth of the story made little difference to Duncan. He was so ill that he had to be placed in care of his family, and could not be moved from Athens.

In 1929 he was appointed by Evans curator of the archaeological site at Knossos in central Crete. The job came with the Taverna; situated on the edge of the site, this house provided accommodation for the married couple and a center for social activities among the archaeologists.

The climatic differences between Greece and Egypt made it possible to excavate in both countries each year.

Pendlebury was one of the early archaeologists who engaged in environmental reconstruction of the Bronze Age; for example, as C. Michael Hogan notes, Pendlebury first deduced that the settlement at Knossos on Crete appears to have been overpopulated at its Bronze Age peak based upon deforestation practices.

Pendlebury was Director of Excavations at Tell el-Amarna from 1930 to 1936 and continued as Curator at Knossos until 1934.

From 1936 he directed excavations on Mount Dikti in eastern Crete and continued there until the war was imminent.

Patrick Leigh Fermor said:

... [Pendlebury] got to know the island inside out. ... He spent days above the clouds and walked over 1,000 miles in a single archaeological season. His companions were shepherds and mountain villagers. He knew all their dialects...."

Manolaki Akoumianos, a Cretan and one of the workers at Knossos, said:

...[he] knew the whole island like his own hand, spoke Greek like a true Cretan, could make up mantinades all night long, and could drink any Cretan under the table.

Anticipating the coming war and strategic nature of Crete, Pendlebury eventually succeeded in convincing the British military authorities of the value of his unique knowledge. They sent him back to England for military training, and in May 1940 he returned to Heraklion (then called by its Italian / Venetian name - Candia) as British Vice Consul, but his job title did not hide from most of the diplomatic community the nature of his duties. He immediately set to working up his outline plans: improving the reconnaissance (routes, hiding places, water sources and chiefly sounding out the local clan chiefs like Antonios Gregorakis and Manolis Bandouvas. Turkey had relinquished control over Crete only 43 years before and these kapetanios would be the key to harnessing the Cretan fighting spirit. In October, on Italy's attempted invasion of Greece, Pendlebury became liaison officer between British troops and Cretan military authorities.

By the time Germany had occupied mainland Greece in April 1941 Pendlebury had laid his plans, unfortunately they could not include the Cretan division of the Greek army which was captured on the mainland. The invasion of Crete started on 20 May 1941, Pendlebury was in the Heraklion area where it started with heavy bombing followed by troops dropped by parachute. The enemy forced an entry into Heraklion but were driven out by regular Greek and British troops and by islanders now armed with assorted weapons.

On 21 May 1941, when German troops took over Heraklion, Pendlebury slipped away with his Cretan friends heading for Krousonas, the village of Kapetanios Satanas, which was some 15km to the southwest. They had the intention of launching a counter attack, but on the way there Pendlebury left the vehicle to open fire on some German troops, who fired back. Some Stukas came over and Pendlebury was shot in the chest. Aristeia Drossoulakis took him into her nearby cottage and he was laid on a bed. The cottage was overrun and a German doctor treated him chivalrously, dressing his wounds; he was later given an injection.

The next day Pendlebury had been changed into a clean shirt. The Germans were setting up a gun position nearby and a fresh party of paratroopers came by. They found Pendlebury who had lost his identity discs and was wearing a Greek shirt. As he was out of uniform and could not prove that he was a soldier, he was put against a wall outside the cottage and shot through the head and the body.

He was buried nearby, later being reburied 1km outside the western gate of Heraklion. He now lies in the cemetery at Souda Bay maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor, DSO, OBE (11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011) was a British author, scholar and soldier, best known as Paddy Fermor, who played a prominent role behind the lines in the Cretan resistance during World War II. He was widely regarded as "Britain's greatest living travel writer", with books including his classic A Time of Gifts (1977). A BBC journalist once described him as "a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene."

He was born in London, the son of Sir Lewis Leigh Fermor, a distinguished geologist, and Muriel Aeyleen (née Ambler). Shortly after his birth, his mother and sister left to join his father in India, leaving the infant in England with a family in Northamptonshire and he did not meet his family until he was four. As a child, Leigh Fermor had problems with academic structure and limitations. As a result, he was sent to a school for "difficult children". He was later expelled from The King's School, Canterbury, when he was caught holding hands with a greengrocer's daughter.

His last report from The King's School noted that the young Fermor was "a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness." He continued learning by reading texts on Greek, Latin, Shakespeare and History, with the intention of entering the Royal Military College Sandhurst. Gradually he changed his mind, deciding to become an author instead, and in the Summer of 1933 relocated to Shepherd Market, living with a few friends. Soon, faced with the challenges of an author's life in London, above all his now drained finances, he set upon leaving for Europe.

At the age of 18, Leigh Fermor decided to walk the length of Europe, from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople. He set off on 8 December 1933, shortly after Hitler had come to power in Germany, with a few clothes, several letters of introduction, the Oxford Book of English Verse and a volume of Horace's Odes. He slept in barns and shepherds' huts, but also was invited by landed gentry and aristocracy into the country houses of Central Europe. He experienced hospitality in many a monastery along the way. Two of his later travel books, A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986), were about this journey.

He arrived in Constantinople on 1 January 1935, then continued to travel around Greece. In March, he was involved in the campaign of royalist forces in Macedonia against an attempted Republican revolt. In Athens, he met Balasha Cantacuzène (Bălaşa Cantacuzino), a Romanian noblewoman, with whom he fell in love. They shared an old watermill outside the city looking out towards Poros, where she painted and he wrote. They moved on to Băleni, the Cantacuzène house in Moldavia, where they were living at the outbreak of World War II.

As an officer cadet, Leigh Fermor trained alongside Derek Bond (actor) and Iain Moncreiffe, and later joined the Irish Guards. Due, however, to his knowledge of modern Greek, he was commissioned in the General List and became a liaison officer in Albania. He fought in Crete and mainland Greece. During the German occupation, he returned to Crete three times, once by parachute. He was one of a small number of Special Operations Executive (SOE) officers posted to organize the island's resistance to German occupation. Disguised as a shepherd and nicknamed Michalis or Filedem, he lived for over two years in the mountains. With Captain Bill Stanley Moss as his second in command, Leigh Fermor led the party that in 1944 captured and evacuated the German Commander, General Heinrich Kreipe. The Cretans commemorate Kreipe's abduction near Archanes.

Moss featured the events in his book Ill Met by Moonlight: The Abduction of General Kreipe (1950). It was later adapted as a film by the same name, directed / produced by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger and released in 1957. In the film, Leigh Fermor was portrayed by Dirk Bogarde.

The Cretan resistance movement had the support of the British while Crete had strategic importance for the North Africa campaign. However once that campaign had been successful, British activity in Crete focused on the second plank of its policy in Greece, which was to undermine the left wing resistance movement. Leigh Fermor set up an alternative movement in 1943, the National Organization of Crete or EOK, funded and supplied by the British.

Among other sources, Sanoudakis refers to a secret report by British agent in Crete Jack Smith Hughes on the actions of the SOE in Crete, 1941 – 45, in which Smith Hughes revealed that Leigh Fermor was present at the EOK's first meeting in February 1943. Cretan writers such as Mihalis Kokolakis have suggested that the killing of two German soldiers in EAM territory by the EOK was at the direction of British agents, who may have hoped that the ensuing bloodbath of German reprisals (the Holocaust of Viannos) would deal a blow to the left wing movement. Kimonas Zografakis, who took part in the abduction of General Heinrich Kreipe later averred that the kidnapping was carried out for the same reason.

Sanoudakis argues in his article "Leigh Fermor was a classic agent" that "Leigh Fermor was neither a great philhellene, nor a new Lord Byron for Greece who fought and loved at the same time. Fundamentally he was a classic agent who served faithfully the interests of Britain and as a cultivated gentleman wrote good travel books. Anything else that the people of Greece attribute to him derives from either ignorance or innocence or anglophilia, ignoring the terrible sufferings he caused our country at that time..."

In fact, Leigh Fermor’s strategy for the kidnapping of Kreipe was to undertake a bloodless operation that would be attributed to British forces alone in order to avoid direct reprisals being meted out against the Cretan population. In this, he was successful.

In 1950, Leigh Fermor published his first book, The Traveller's Tree, about his post war travels in the Caribbean. The book won the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature and established his career path: it was quoted extensively in Live and Let Die, by Ian Fleming. He went on to write several further books of his journeys, including Mani and Roumeli, of his travels on mule and foot around remote parts of Greece. Critics and discerning readers regard his 1977 A Time of Gifts as one of the greatest travel books in the English language.

Leigh Fermor translated the manuscript, The Cretan Runner, written by George Psychoundakis, the dispatch runner on Crete during the war. Leigh Fermor helped Psychoundakis get his work published. Leigh Fermor wrote a novel, The Violins of Saint - Jacques. It was adapted as an opera by Malcolm Williamson. His friend Lawrence Durrell, in Bitter Lemons (1957), recounts how, during the outbreak of Cypriot insurgency against continued British rule in 1955, Leigh Fermor visited Durrell's villa in Bellapais, Cyprus:

"After a splendid dinner by the fire he starts singing, songs of Crete, Athens, Macedonia. When I go out to refill the ouzo bottle... I find the street completely filled with people listening in utter silence and darkness. Everyone seems struck dumb. 'What is it?' I say, catching sight of Frangos. 'Never have I heard of Englishmen singing Greek songs like this!' Their reverent amazement is touching; it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes."

After many years together, Leigh Fermor was married in 1968 to the Honorable Joan Elizabeth Rayner (née Eyres Monsell), daughter of the 1st Viscount Monsell. She accompanied him on many of his travels until her death in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. They had no children. They lived part of the year in their house in an olive grove near Kardamyli in the Mani Peninsula, southern Peloponnese, and part of the year in Worcestershire. Leigh Fermor was knighted in the 2004 New Years Honors. In 2007, he said that, for the first time, he had decided to work using a typewriter - having written all his books longhand until then.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was noted for his strong physical constitution. Although in his last years he suffered from tunnel vision and wore hearing aids he remained physically fit up to his death and dined at table on the last evening of his life. For the last few months of his life he suffered from a tumor, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy. As death was close, he expressed a wish to die in England and returned there on 9 June 2011. He died the following day, aged 96, following this short battle with cancer.

The funeral took place at St Peter's Church, Dumbleton, on 16 June 2011. A Guard of Honor was provided by serving and former members of the Intelligence Corps, and a bugler from the Irish Guards sounded the Last Post and reveille. Leigh Fermor is buried next to his wife in the churchyard at Dumbleton.

John Murray announced it will publish the final volume of his Leigh Fermor's journey to Constantinople in 2013, drawing from his diary at the time and an early draft he wrote in the 1960s.