<Back to Index>

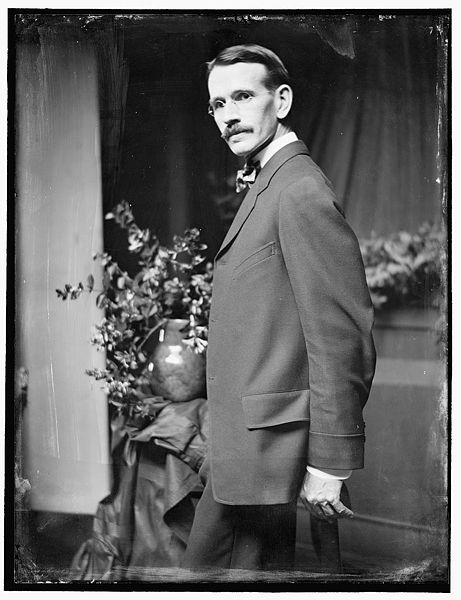

- Painter Arthur Bowen Davies, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

Arthur Bowen Davies (September 26, 1862 - October 24, 1928) was an avant-garde American artist and influential advocate of modern art in the United States c. 1910 - 1928.

Davies was born in Utica, New York, the son of David and Phoebe Davies. He was keenly interested in drawing when he was young and, at fifteen, attended a large touring exhibition in his hometown of American landscape art, featuring works by George Inness and members of the Hudson River School. The show had a profound effect on him. He was especially impressed by Inness's tonalist landscapes. After his family relocated to Chicago, Davies studied at the Chicago Academy of Design from 1879 to 1882 and briefly attended the Art Institute of Chicago, before moving to New York City, where he studied at the Art Students League. He worked as a magazine illustrator before devoting himself to painting.

In 1892, Davies married Virginia Meriwether, one of New York State's first female physicians. Her family, suspecting that their daughter might end by being the sole breadwinner of the family if she was to marry an impoverished artist, insisted that the bridegroom sign a prenuptial agreement, renouncing any claim on his wife's money in the event of divorce. (Davies would eventually become very wealthy through the sale of his paintings, though his prospects at thirty did not look encouraging.) Appearances notwithstanding, they were anything but a conventional couple, even aside from the fact that Davies was of a philandering nature. Virginia had eloped when she was young and had murdered her husband on her honeymoon when she discovered that he was an abusive drug addict and compulsive gambler, a fact that she and her family kept from Davies. When Davies died in 1928, Virginia discovered that he had kept hidden a second life, with another common law wife, Edna, and family. Edna discovered that she was given a subsistence allowance by Arthur, despite his financial success as an artist.

An urbane man with a formal demeanor, Arthur B. Davies was "famously diffident and retiring". He would rarely invite anyone to his studio and, later in life, would go out of his way to avoid old friends and acquaintances. The reason for Davies' reticence became known after his sudden death while vacationing in Italy in 1928: he had two wives (one legal, one common law) and children by each of them, a secret kept from Virginia for twenty-five years. With Virginia, he had two sons, Niles and Arthur.

Within a year of his marriage, Davies' paintings began to sell, slowly but steadily.

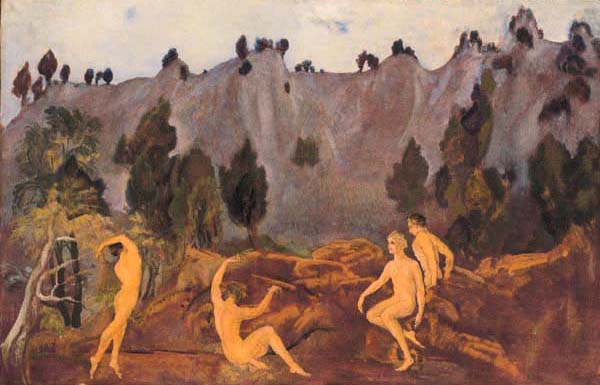

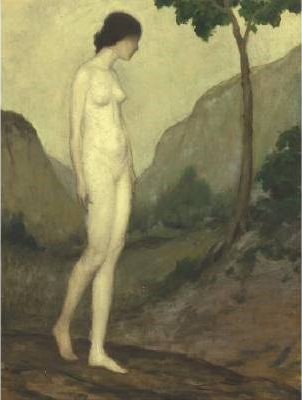

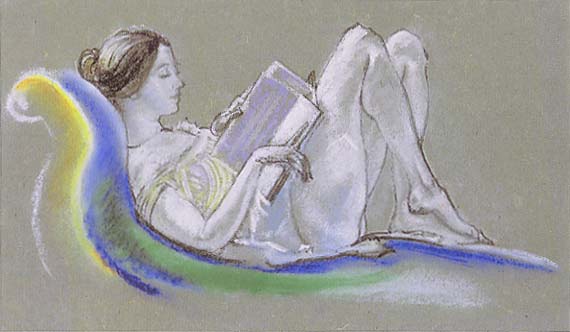

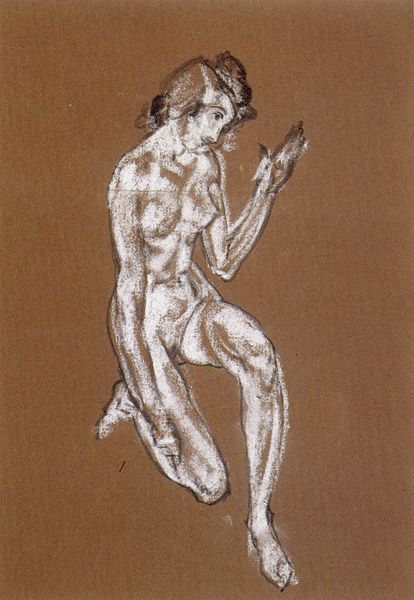

In turn - of - the - century America, he found a market for his gentle,

expertly painted evocations of a fantasy world. Regular trips to Europe,

where he immersed himself in Dutch art and came to love the work of Corot and Millet,

helped him to hone his color sense and refine his brushwork. By the

time he was in his forties, Davies had definitively proved his in-laws

wrong and, represented by a prestigious Manhattan art dealer, William

Macbeth, was making a comfortable living. His reputation at the time,

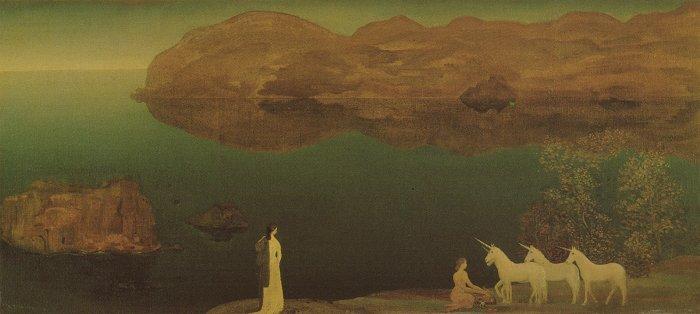

and still today (to the extent that he is known at all), rests on his

ethereal figure paintings, the most famous of which is Unicorns: Legend, Sea Calm

(1906) in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the

1920s, his works commanded very high prices and he was recognized as one

of the most respected and financially successful American painters. He

was prolific, consistent, and highly skilled. Art history texts

routinely cited him as one of America's greatest artists. Important

collectors like Duncan Phillips were eager to buy his latest drawings,

watercolors, and oil paintings.

Davies was also the principal organizer of the legendary 1913 Armory Show and a member of The Eight, a group of painters who in 1908 mounted a protest against the restrictive exhibition practices of the powerful, conservative National Academy of Design. Five members of the Eight — Robert Henri (1865 - 1929), George Luks (1867 - 1933), William Glackens, (1870 - 1938), John Sloan, (1871 - 1951), and Everett Shinn (1876 - 1953) — were Ashcan realists, while Davies, Maurice Prendergast (1859 - 1924), and Ernest Lawson (1873 - 1939) painted in a different, less realistic style. His friend Alfred Stieglitz, patron to many modern artists, regarded Davies as more broadly knowledgeable about contemporary art than anyone he knew. Davies also served as an advisor to many wealthy New Yorkers who wanted guidance about making purchases for their art collections. Two of those collectors were Lizzie P. Bliss and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, two of the founders of the Museum of Modern Art, whose Davies - guided collections eventually became a core part of that museum.

Davies was quietly but remarkably generous in his support of fellow artists. He was a mentor to the gifted but deeply troubled sculptor John Flannagan, whom he rescued from dire poverty and near-starvation. He helped finance Marsden Hartley's 1912 trip to Europe, which resulted in a major phase of Hartley's career. He recommended to his own dealer financially strapped artists whose talent he believed in, like Rockwell Kent.

Yet Davies made enemies as well. His role in organizing the Armory Show, a massive display of modern art which proved somewhat threatening to American realists like Robert Henri, the leader of The Eight, showed a forceful side to his character that many in the art world had never seen. With fellow artists Walt Kuhn and Walter Pach, he devoted himself with great zeal to the project of scouring Europe for the best examples of Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism and publicizing the exhibition in New York and later in Chicago and Boston. Those who did not fully support the venture or expressed any reservations, like his old colleague Henri, were treated with contempt. Davies knew in which direction the tide of art history was flowing and displayed little tolerance for those who could not keep pace.

In an official statement for a pamphlet that was sold at the Chicago venue of the Armory Show and later reprinted in The Outlook

magazine, Davies wrote: "In getting together the works of the European

Moderns, the Society [i.e., the organizing body for the Armory Show, the

Association of American Painters and Sculptors] has embarked on no

propaganda. It proposes to enter on no controversy with any

institution ... Of course, controversies will arise, but they will not

be the result of any stand taken by the Association as such."

With these masterfully disingenuous words, Davies pretended that the

men who had brought some of the most radical contemporary art to the

United States were merely offering Americans an opportunity for a

dispassionate viewing experience. In reality, Davies, Kuhn, and Pach

knew that their bold project was likely to alter, decisively and

permanently, the cultural landscape of America.

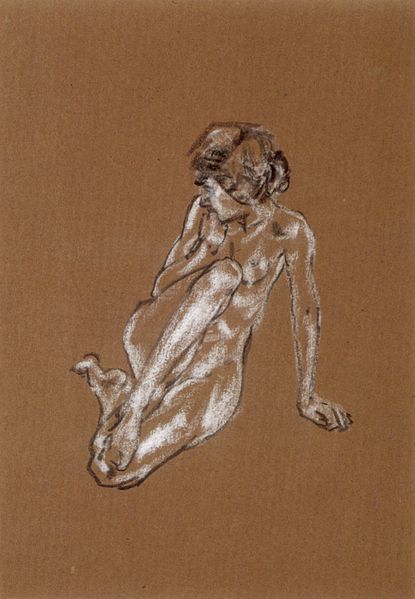

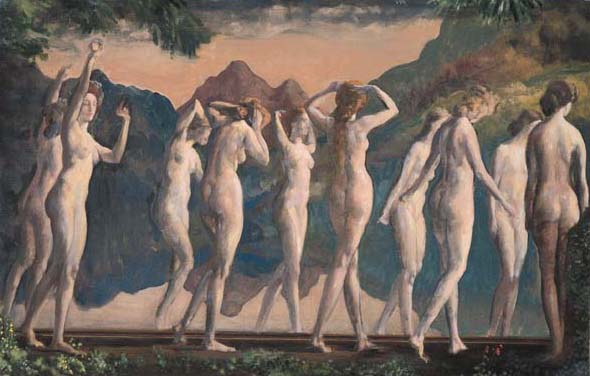

Arthur B. Davies is an anomaly in American art history, an artist whose own lyrical work could be described as restrained and conservative but whose tastes were as advanced and open to experimentation as those of anyone of his time. (His personal art collection at the time of his death included works by Alfred Maurer, Marsden Hartley, and Joseph Stella as well as major European modernists like Cézanne and Brâncuși.) As art historian Milton Brown wrote of Davies' early period, "A product of the Tonalist school and Whistler, he had developed a unique decorative style. He was completely eclectic," with influences that ranged from Hellenistic Greek art to Sandro Botticelli, the German painter Arnold Böcklin, and the English Pre-Raphaelites. A painter of dream - like maidens and "frieze - like idylls," he was most often compared to the French artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. His involvement with the Armory Show and prolonged exposure to European Modernism, however, changed his outlook utterly. As art historian Sam Hunter wrote, "[One] could scarcely have guessed that the bold colors of Matisse and the radical simplifications of the Cubists would engage Davies' sympathies," but so they did. His subsequent work attempted to merge stronger color and a Cubist sense of structure and Cubist forms with his on-going preoccupation with the female body, delicate movement, and an essentially romantic outlook (e.g., Day of Good Fortune, in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art.) "Mr. Davies takes his Cubism lightly," a sympathetic critic wrote in 1913, acknowledging a view, held then and now, that Davies' Cubist-inspired paintings have an elegant appeal but are not in the more rigorous or authentic spirit of Cubism as practiced by Picasso, Georges Braque and Juan Gris.

By 1918, Davies returned, in large part, to his earlier style. Kimberly Orcutt plausibly speculates that Davies found the mixed reactions (and sometimes very negative responses) to his more modernist explorations distressing and so "returned to the style that was expected of him, the one that had brought him praise and prosperity." A traditionalist, a visionary, an Arcadian fantasist, an advocate for Modernism: varied and seemingly contradictory designations describe Arthur B. Davies.