<Back to Index>

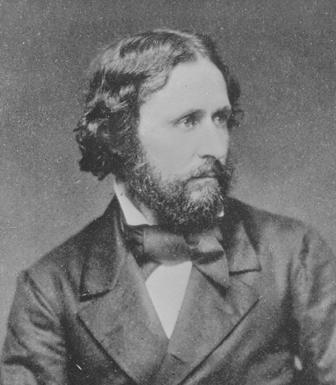

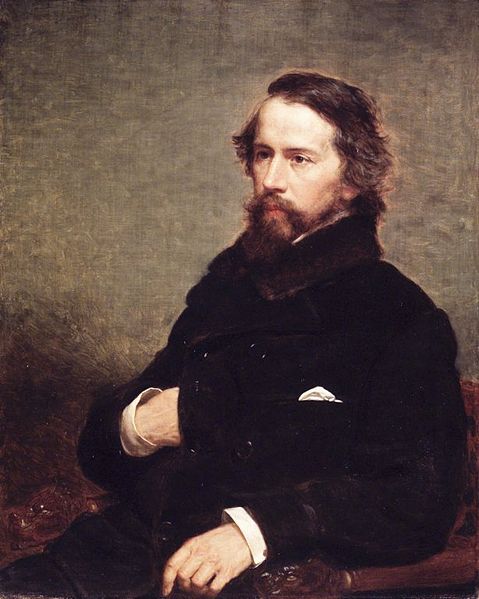

- Major General of the U.S. Army, Military Governor of California, Senator and Territorial Governor of Arizona John Charles Frémont, 1813

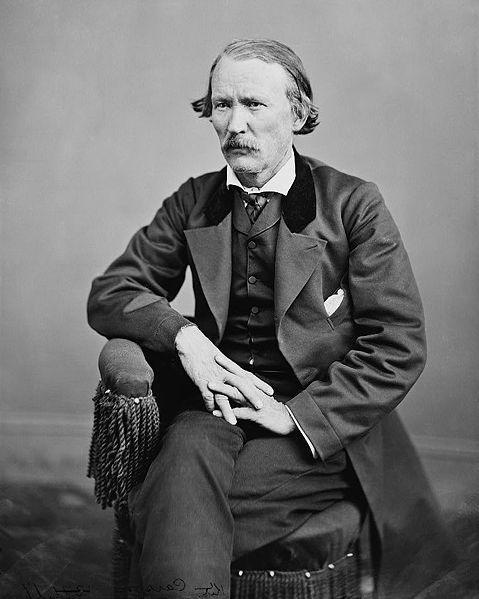

- Frontiersman and Officer of the Union Army Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson, 1809

PAGE SPONSOR

John Charles Frémont (January 21, 1813 – July 13, 1890), was an American military officer, explorer, and the first candidate of the anti - slavery Republican Party for the office of President of the United States. During the 1840s, that era's penny press accorded Frémont the sobriquet The Pathfinder. He is sometimes called The Great Pathfinder. He retired from the military and moved to the new territory California, after leading a fourth expedition which cost ten lives seeking a rail route over the mountains around the 38th parallel in the winter of 1849.

He became one of the first two U.S. Senators elected from the new state in 1850. He was soon bogged down with lawsuits over land claims between the dispossessions of various land owners during the Mexican - American War, and the explosion of Forty - Niners immigrating during the California Gold Rush. He lost the 1856 presidential election to Democrats James Buchanan and John C. Breckenridge when Democrats warned his election would lead to civil war.

During the American Civil War he was given command of the armies in the west but made hasty decisions (such as trying to abolish slavery without consulting the federal government), and was consequently relieved of his command (fired, then court martialed – receiving a presidential pardon).

Historians portray Frémont as controversial, impetuous and contradictory. Some scholars regard him as a military hero of significant accomplishment, while others view him as a failure who repeatedly defeated his own best purposes. The keys to Frémont's character and personality may lie in his being born out of wedlock, ambitious drive for success, self - justification, and passive - aggressive behavior.

Frémont's mother, Anne Beverley Whiting, was the youngest daughter of socially prominent Virginia planter Col. Thomas Whiting. The colonel died when Anne was less than a year old. Her mother married Samuel Cary, who soon exhausted most of the Whiting estate. At age 17 Anne married Major John Pryor, a wealthy Richmond resident in his early 60s. In 1810 Pryor hired Charles Fremon, a French immigrant who had fought with the Royalists during the French Revolution, to tutor his wife. In July 1811 Pryor learned that Whiting and Fremon were having an affair. Confronted by Pryor, the couple left Richmond together on July 10, 1811, creating a scandal that shook city society. Pryor published a divorce petition in the Virginia Patriot, in which he charged that his wife had "for some time past indulged in criminal intercourse". Whiting and Fremon moved first to Norfolk, Virginia, and later settled in Savannah, Georgia. Whiting financed the trip and purchase of a house in Savannah by selling recently inherited slaves valued at $1,900. When the Virginia House of Delegates refused Pryor’s divorce petition, it was impossible for the couple to marry. In Savannah, Whiting took in boarders while Fremon taught French and dancing. On January 21, 1813, their first child, John Charles Fremont, was born. Their son was born out of wedlock, a social handicap which he overcame later with his marriage to the daughter of a powerful U.S. senator.

In Andrew Jackson, His Life and Times, H. W. Brands wrote that Frémont added the accented "e" and the "t" to his name later in life. But in John Charles Frémont: Character as Destiny, Andre Rolle wrote that Charles Fremon was originally named Louis - René Frémont and had changed his name to Charles Fremon or Frémon upon emigrating to Virginia. Thus, John was reclaiming his father's (and family's) true French name.

In 1841 John C. Frémont married Jessie Benton, daughter of Sen. Thomas Hart Benton from Missouri. Benton, Democratic Party leader for more than 30 years in the Senate, championed the expansionist movement, a political cause that became known as Manifest Destiny. The expansionists believed that the North American continent, from one end to the other, north and south, east and west, should belong to the citizens of the U.S. They believed it was the nation's destiny to control the continent. This movement became a crusade for politicians such as Benton and his new son - in - law. Benton pushed appropriations through Congress for national surveys of the Oregon Trail (1842), the Oregon Territory (1844), the Great Basin and Sierra Mountains to California (1845). Through his power and influence, Benton obtained for Frémont the position of leading each expedition.

After attending the College of Charleston from 1829 to 1831, Frémont was appointed a teacher of mathematics aboard the sloop USS Natchez. In July 1838 he was appointed a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers and assisted and led multiple surveying expeditions through the western territory of the United States and beyond. In 1838 and 1839 he assisted Joseph Nicollet in exploring the lands between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. In 1841 with training from Nicollet, Frémont mapped portions of the Des Moines River.

Frémont first met frontiersman Kit Carson on a Missouri River steamboat in St. Louis during the summer of 1842. Frémont was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass. Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five month journey, made with 25 men, was a success.

From 1842 to 1846 Frémont and his guide Carson led expedition parties on the Oregon Trail and into the Sierra Nevada. During his expeditions in the Sierra Nevada, Frémont became the first American to see Lake Tahoe. He is also credited with determining the Great Basin as endorheic, that is, having no outlet to the sea or a river. One of Frémont's reports from an expedition inspired the Mormons to consider Utah for settlement. He also mapped volcanoes such as Mount St. Helens.

Congress published Frémont's "Report and Map"; it guided thousands of overland immigrants to Oregon and California from 1845 to 1849. In 1849 Joseph Ware published his Emigrants' Guide to California, which was largely drawn from Frémont's report, and was to guide the forty - niners through the California Gold Rush. Frémont's report was more than a travelers' guide – it was a government publication that achieved the expansionist objectives of a nation and provided scientific and economic information concerning the potential of the trans - Mississippi West for pioneer settlement.

On June 1, 1845, John Frémont and 55 men left St. Louis, with Carson as guide, on the third expedition. The stated goal was to locate the source of the Arkansas River, on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Upon reaching the Arkansas, however, Frémont suddenly made a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in the Sacramento Valley in early 1846, he promptly sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the American settlers there. He promised that if war with Mexico started, his military force would protect the settlers. Frémont nearly provoked a battle with Gen. José Castro near Monterrey, camped at the summit of what is now named Fremont Peak. A conflict would likely have resulted in the annihilation of Frémont's group, as Gen. Castro had the ability to organize thousands of troops. Frémont then fled Mexican controlled California, and went north to Oregon, making camp at Klamath Lake.

After a May 9, 1846 Indian attack on his expedition party, Frémont retaliated by attacking a Klamath Indian fishing village named Dokdokwas the following day, although the people living there might not have been involved in the first action. The village was at the junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake. On May 10, 1846, the Frémont group completely destroyed it. Afterward, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior. As Carson's gun misfired, the warrior drew to shoot a poison arrow; however, Frémont, seeing that Carson was in danger, trampled the warrior with his horse. Carson felt that he owed Frémont his life.

After meeting with President James K. Polk, he left Washington, D.C. on May 15, 1845. He raised a group of 62 volunteers in Saint Louis. He arrived at Sutter's Fort in California on December 10, 1845. He went to Monterrey, California, to talk with the American consul, Thomas Larkin, and Mexican major-domo Jose Castro.

In 1846, with the arrival of USS Congress, Frémont was appointed lieutenant colonel of the California Battalion, also called U.S. Mounted Rifles, which he had helped form with his survey crew and volunteers from the Bear Flag Republic, now totaling 428 men.

In June 1846, at San Rafael mission, John Frémont sent three men, one of whom was Kit Carson, to confront three unarmed men debarking from a boat at Point San Pedro. Kit Carson asked John Frémont whether they should be taken prisoner. Frémont replied, "I have got no room for prisoners." They then advanced on the three and deliberately shot and killed them. One of them was an old and respected Californian, Don Jose R. Berreyesa, whose son was the Alcalde of Sonoma who had been recently imprisoned by Frémont. The two others were twin brothers and sons of Don Francisco de Haro of Yerba Buena, who had served two terms as the first and third Alcalde of Yerba Buena (later named San Francisco).

These murders were observed by Jasper O’Farrell, a famous architect and designer of San Francisco, who wrote a letter detailing it to the Los Angeles Star published on September 27, 1856. This eyewitness account, together with others, were widely published during the presidential election of 1856, which featured John Frémont as the first anti - slavery Republican nominee versus Democrat James Buchanan. It is widely speculated that this incident, together with other military blunders, sank Frémont’s political aspirations.

In late 1846 Frémont, acting under orders from Commodore Robert F. Stockton, led a military expedition of 300 men to capture Santa Barbara, California, during the Mexican - American War. Frémont led his unit over the Santa Ynez Mountains at San Marcos Pass in a rainstorm on the night of December 24, 1846. In spite of losing many of his horses, mules and cannons, which slid down the muddy slopes during the rainy night, his men regrouped in the foothills the next morning, and captured the presidio without bloodshed, thereby capturing the town. A few days later Frémont led his men southeast toward Los Angeles, accepting the surrender of the leader Andres Pico and signing the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13, 1847, which terminated the war in upper California.

On January 16, 1847, Commodore Stockton appointed Frémont military governor of California following the Treaty of Cahuenga. However, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, who outranked both Stockton and Frémont, had orders from President Polk and secretary of war William L. Marcy to serve as military governor. He asked Frémont to give up the governorship, which the latter stubbornly refused to do before finally relenting. Ordered to march with Kearny's army back east, Frémont was arrested on August 22, 1847 when they arrived at Fort Leavenworth. He was charged with mutiny, disobedience of orders, assumption of powers, along with several other military offenses. Ordered by Kearny to report to the adjutant general in Washington to stand for court martial, Frémont was convicted of mutiny, disobedience of a superior officer and military misconduct.

While approving the court's decision, Pres. James K. Polk quickly commuted his sentence of dishonorable discharge due to his services. Frémont resigned his commission and settled in California. In 1847 he purchased the Rancho Las Mariposas land grant in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains near Yosemite.

In 1848 Frémont and his father - in - law Sen. Benton developed a plan to advance their vision of Manifest Destiny, as well as restore Frémont's honor after his court martial. With a keen interest in the potential of railroads, Sen. Benton had sought support from the Senate for a railroad connecting St. Louis to San Francisco along the 38th parallel, the latitude which both cities approximately share. After Benton failed to secure federal funding, Frémont secured private funding. In October 1848 he embarked with 35 men up the Missouri, Kansas and Arkansas rivers to explore the terrain.

On his party's reaching Bent's Fort, he was strongly advised by most of the trappers against continuing the journey. Already a foot of snow was on the ground at Bent's Fort, and the winter in the mountains promised to be especially snowy. Part of Frémont's purpose was to demonstrate that a 38th parallel railroad would be practical year round. At Bent's Fort he engaged "Uncle Dick" Wootton as guide, and at what is now Pueblo, Colorado, he hired the eccentric "Old Bill" Williams and moved on.

Had Frémont continued up the Arkansas, he might have succeeded. On November 25 at what is now Florence, Colorado, he turned sharply south. By the time his party crossed the Sangre de Cristo Range via Mosca Pass, they had already experienced days of bitter cold, blinding snow and difficult travel. Some of the party, including the guide Wootton, had already turned back, concluding that further travel would be impossible. Although the passes through the Sangre de Cristo had proven too steep for a railroad, Frémont pressed on. From this point the party might still have succeeded had they gone up the Rio Grande to its source, or gone by a more northerly route, but the route they took brought them to the very top of Mesa Mountain. By December 12, on Boot Mountain, it took ninety minutes to progress three hundred yards. Mules began dying and by December 20, only 59 animals remained alive. It was not until December 22 that Frémont acknowledged that the party needed to regroup and be resupplied. They began to make their way to Taos, New Mexico. By the time the last surviving member of the expedition made it to Taos on February 12, 1849, 10 of the party had died. Except for the efforts of member Alexis Godey, another 15 would have been lost. After recuperating in Taos, Frémont and only a few of the men left for California via an established southern trade route.

Frémont was one of the first two senators from California, serving only a few months, from 1850 to 1851. He had previously served as Military Governor of California in 1847.

Frémont was the first presidential candidate of the new Republican Party in 1856. It used the slogan "Free Soil, Free Men, and Frémont" to crusade for free farms (homesteads) and against the Slave Power. As was typical in presidential campaigns, the candidates stayed at home and said little. The Democrats meanwhile counter crusaded against the Republicans, warning that a victory by Frémont would bring civil war. They also raised a host of issues, alleging Frémont was a Catholic and had a poor military record. Frémont's powerful father - in - law, Senator Benton, praised Frémont but announced his support for the Democratic candidate James Buchanan.

At the time of his campaign he lived in Staten Island, New York. The campaign was headquartered near his home in St. George. He placed second to James Buchanan in a three way election; he did not carry the state of California.

He later served as Governor of the Arizona Territory for several years, though he spent little time in the territory; he was asked to resume his duties or resign, and chose resignation.

Frémont later served as a major general in the American Civil War, including a controversial term as commander of the Army's Department of the West from May to November 1861. Frémont replaced William S. Harney, who had negotiated the Harney - Price Truce, which permitted Missouri to remain neutral in the conflict as long as it did not send men or supplies to either side.

Frémont ordered his Gen. Nathaniel Lyon to formally bring Missouri into the Union cause. Lyon had been named the temporary commander of the Department of the West, before Frémont ultimately replaced Lyon. Lyon, in a series of battles, evicted Gov. Claiborne Jackson and installed a pro - Union government. After Lyon was killed in the Battle of Wilson's Creek in August, Frémont imposed martial law in the state, confiscating secessionists' private property and emancipating slaves. On October 25, 1861, Frémont's forces won the First Battle of Springfield.

Pres. Abraham Lincoln, fearing that Frémont's emancipation order would tip Missouri (and other slave states in Union control) to the southern cause, asked Frémont to revise the order. Frémont refused to do so, and sent his wife to plead the case. Lincoln responded by publicly revoking the proclamation and relieving Frémont of command on November 2, 1861, simultaneous to a War Department report detailing Frémont's iniquities as a major general. In March 1862 he was placed in command of the Mountain Department of Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Early in June 1862 Frémont pursued the Confederate Gen. Stonewall Jackson for eight days, finally engaging him at Battle of Cross Keys on June 8. Jackson slipped away after the battle, saving his army.

When the Army of Virginia was created June 26, to include Gen. Frémont's corps, with John Pope in command, Frémont declined to serve on the grounds that he was senior to Pope and for personal reasons. He then went to New York where he remained throughout the war, expecting a command, but none was given to him.

In 1860 the Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln for president, who won the presidency and then ran for reelection in 1864. The Radical Republicans, a group of hard line abolitionists, were upset with Lincoln's positions on the issues of slavery and post war reconciliation with the southern states. On May 31, 1864, they nominated Frémont for president. This fissure in the Republican Party divided the party into two factions: the anti - Lincoln Radical Republicans, who nominated Frémont, and the pro - Lincoln Republicans.

Frémont abandoned his political campaign in September 1864, after he brokered a political deal in which Lincoln removed Postmaster General Montgomery Blair from office.

The state of Missouri took possession of the Pacific Railroad in February 1866, when the company defaulted in its interest payment. In June 1866 the state, at private sale, sold the road to Frémont. Frémont reorganized the assets of the Pacific Railroad as the Southwest Pacific Railroad in August 1866. In less than a year (June 1867), the railroad was repossessed by the state of Missouri after Frémont was unable to pay the second installment on his purchase.

From 1878 to 1881 Frémont was governor of the Arizona Territory. Destitute, the family depended on the publication earnings of his wife Jessie.

Frémont lived on Staten Island in retirement. He died in New York City in 1890 of peritonitis and was buried in Rockland Cemetery, Sparkill, New York.

Frémont collected a number of plants on his expeditions, including the first recorded discovery of the Single - leaf Pinyon by a European American. The genus of the California Flannelbush (Fremontodendron californicum) is named for him, as are the species names of many other plants, including the chaff bush eytelia (Amphipappus fremontii), Western rosinweed (Calycadenia fremontii), pincushion flower (Chaenactis fremontii), goosefoot (Chenopodium fremontii), silk tassel (Garrya fremontii), moss gentian (Gentiana fremontii), vernal pool goldfields (Lasthenia fremontii), tidytips (Layia fremontii), desert pepperweed (Lepidium fremontii), desert boxthorn (Lycium fremontii), barberry (Mahonia fremontii), bush mallow (Malacothamnus fremontii), monkeyflower (Mimulus fremontii), phacelia (Phacelia fremontii), desert combleaf (Polyctenium fremontii), cottonwood tree (Populus fremontii), desert apricot (Prunus fremontii), indigo bush (Psorothamnus fremontii), mountain ragwort (Senecio fremontii), yellowray gold (Syntrichopappus fremontii) and chaparral death camas (Toxicoscordion fremontii).

- Four US states named counties in his honor: Colorado, Idaho, Iowa and Wyoming.

- Several states also named cities, villages and towns after him, such as California, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Ohio, Utah and Wisconsin.

- Likewise, Fremont Peak in the Wind River Mountains and Fremont Peak in San Benito County, California, are also named for the explorer.

- The

Fremont River, a tributary of the Colorado River in southern Utah, was

named after Frémont, as was Fremont Island in the Great Salt Lake.

- Archaeologists named the prehistoric Fremont culture after the river, as the first archaeological sites of the culture were discovered near its course.

- The Seattle neighborhood of Fremont is indirectly named for him, as it was named after the hometown of the early residents from Fremont Nebraska

The city of Elizabeth, South Australia (now a part of the city of Playford) named a local park and high school Fremont in recognition of the sister city relationship it had with Fremont, California. The high school has since merged with Elizabeth High School, so the Pathfinder's legacy is carried by Fremont - Elizabeth City High School.

The "largest and most expensive 'trophy'" in college football is a replica of a cannon "that accompanied Captain John C. Frémont on his expedition through Oregon, Nevada and California in 1843 – 44". The annual game between the University of Nevada, Reno, and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is for possession of the Fremont Cannon.

A barbershop chorus in Fremont, Nebraska, is named The Fremont Pathfinders. The Fremont Pathfinders Artillery Battery is an American Civil War reenactment group from the same community.

Fremont Street in Las Vegas, Nevada, is named in his honor, as are streets in Minneapolis, Minnesota; Kiel, Wisconsin; Manhattan, Kansas; Portland, Oregon; Grant City, Staten Island, New York; Tempe, Arizona; and Tucson, Arizona, as well as several cities in California: Fremont, Monterey, Seaside, Stockton, San Mateo, San Francisco and Santa Clara.

Portland, Oregon also has several other locations named after Frémont, such as Fremont Bridge. Other places named for him include John C. Fremont Senior High School in Los Angeles, Fremont High School in Plain City, Utah, and Fremont Senior High School in Oakland, and the John C. Fremont Branch Library located on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles. Elementary schools in Glendale, California; Modesto, California; Long Beach, California; and Carson City, Nevada, bear his name, as do junior high or middle schools in Mesa, Arizona; Pomona, California; Las Vegas, Nevada; Roseburg, Oregon; and Oxnard, California. Fremont High School in Sunnyvale, California, is named for the explorer and its annual yearbook is called The Pathfinder. In addition, the Fremont Hospital in Yuba City, California, and the John C. Fremont Hospital, in Mariposa, California, (where Frémont and his wife lived and prospered during the Gold Rush) are named for him. There is also a John C. Fremont Library in Florence, Colorado.

- The U.S. Army's (now inactive) 8th Infantry Division (Mechanized) is called the Pathfinder Division, after John Frémont. The gold arrow on the 8th ID crest is called the "Arrow of General Frémont."

- The 1983 historical novel Dream West by western writer David Nevin covers the life, loves and times of Frémont. The novel was later adapted into a television miniseries of the same name with Richard Chamberlain as Frémont.

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman and Indian fighter. Carson left home in rural present day Missouri at age 16 and became a mountain man and trapper in the West. Carson explored the west to California, and north through the Rocky Mountains. He lived among and married into the Arapaho and Cheyenne tribes. He was hired by John C. Fremont as a guide, and led 'the Pathfinder' through much of California, Oregon and the Great Basin area. He achieved national fame through Fremont's accounts of his expeditions. He became the hero of many dime novels.

Carson was a courier and scout during the Mexican - American war from 1846 to 1848, celebrated for his rescue mission after the Battle of San Pasqual and his coast - to - coast journey from California to deliver news of the war to the U.S. government in Washington, D.C.. In the 1850s, he was the Agent to the Ute and Jicarilla Apaches. In the Civil War he led a regiment of mostly Hispanic volunteers at the Battle of Valverde in 1862. He led armies to pacify the Navajo, Mescalero Apache, and the Kiowa and Comanche Indians. He is vilified for his conquest of the Navajo and their forced transfer to Bosque Redondo where many of them died. Breveted a general, he is probably the only American to reach such a high military rank without being able to read or write, although he could sign his name.

Kit Carson's alliterative name, adventurous life and participation in a large number of historical events has made him a favorite subject of novelists, historians and biographers.

Born in Madison County, Kentucky, near the city of Richmond, in 1809, Carson moved at the age of one year with his parents and siblings to a rural area near Franklin, Missouri. Carson's father, Lindsey Carson, a farmer of Scots - Irish descent, had fought in the Revolutionary War under General Wade Hampton. He had a total of fifteen Carson children: five by Lucy Bradley, his first wife, and ten by Kit Carson's mother, Rebecca Robinson. Kit Carson was the eleventh child in the family. He was known from an early age as "Kit". The Carson family settled on a tract of land owned by the sons of Daniel Boone, who had purchased the land from the Spanish prior to the Louisiana Purchase. The Boone and Carson families became good friends, working and socializing together, and intermarrying.

Carson was eight years old when his father was killed by a falling tree while clearing land. Lindsey Carson's death reduced the Carson family to a desperate poverty, forcing young Kit Carson to drop out of school to work on the family farm, as well as to engage in hunting. At age 14 Carson was apprenticed to a saddlemaker (Workman's Saddleshop) in the settlement of Franklin, Missouri. Franklin was situated at the eastern end of the Santa Fe Trail, which had opened two years earlier. Many of the clientele at the saddleshop were trappers and traders, from whom Carson heard stirring tales of the Far West. Carson is reported to have found work in the saddle shop suffocating: he once stated "the business did not suit me, and I concluded to leave". His master may have agreed with his leaving since he offered the odd amount of 1 cent for his return and waited a month to post the notice in the local newspaper.

At sixteen, Carson secretly signed on with a large merchant caravan heading to Santa Fe — with the job of tending the horses, mules and oxen. During the winter of 1826 – 1827 he stayed with Matthew Kinkead, a trapper and explorer, in Taos, New Mexico, then known as the capital of the fur trade in the Southwest. Kinkead had served with Carson's older brothers during the War of 1812, and he taught Carson the skills of a trapper. Carson also began learning the necessary languages. Eventually he became fluent in Spanish, Navajo, Apache, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Paiute, Shoshone and Ute.

After gaining experience as a teamster along the Santa Fe Trail and in Mexico, Carson signed on with a party of forty men, led by Ewing Young which in August, 1829 went into Apache country along the Gila River. There, when the party was attacked, Carson first saw combat. Young's party continued on into California trapping and trading from Sacramento to Los Angeles, returning to Taos in April, 1830 after trapping along the Colorado River.

At the age of 25, in the summer of 1835, Carson attended an annual mountain man rendezvous, which was held along the Green River in southwestern Wyoming. He became interested in an Arapaho woman whose name, Waa-Nibe, is approximated in English as "Grass Singing" Her tribe was camped nearby the rendezvous. Singing Grass is said to have been popular at the rendezvous and also to have caught the attention of a French - Canadian trapper, Joseph Chouinard. When Singing Grass chose Carson over Chouinard, the rejected suitor became belligerent. Chouinard is reported to have thrown a fit, disrupting the camp to the point where Carson could no longer tolerate the situation. Words were exchanged, and Carson and Chouinard charged each other on horses while brandishing their weapons. Using a pistol, Carson blew off Chouinard's thumb. His opponent barely missed killing Carson with his rifle shot; it grazed below his left ear and scorched his eye and hair. Carson said that the fact that Chouinard's horse shied probably saved him, as Chouinard was a splendid shooter

Controversy regarding Chouinard's fate continues. The duel with Chouinard is said to have made Carson famous among the mountain men but was also considered uncharacteristic of him.

Carson considered his years as a trapper to be "the happiest days of my life." Accompanied by Singing Grass, he worked with the Hudson's Bay Company, as well as the renowned frontiersman Jim Bridger, trapping beaver along the Yellowstone, Powder and Big Horn rivers. They trapped throughout what is now Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana. Carson's first child, a daughter named Adeline, was born in 1837. Singing Grass gave birth to a second daughter but developed a fever shortly after the birth, and died sometime between 1838 – 1840.

At this time, the nation was undergoing a severe depression (Panic of 1837). In addition, the fur industry was undermined by changing fashion styles: a new demand for silk hats replaced the demand for beaver fur. Also, the trapping industry had devastated the beaver population. These factors ended the need for trappers. Carson said, "Beaver was getting scarce, it became necessary to try our hand at something else."

He attended the last mountain man rendezvous, held in the summer of 1840 (again at Ft. Bridger near the Green River) and moved on to Bent's Fort, finding employment as a hunter. Carson married a Cheyenne woman, Making - Our - Road, in 1841. She left him only a short time later to follow her tribe's migration.

By 1842 Carson met and became engaged to the daughter of a prominent Taos family: Josefa Jaramillo. After receiving instruction from Padre Antonio José Martínez, he was baptized into the Catholic Church in 1842. At 34, Carson married his third wife, 14 year old Josefa, on February 6, 1843. They had eight children together, the descendants of whom remain in the Arkansas Valley of Colorado.

Carson decided early in 1842 to return to Missouri, taking his daughter Adeline to live with relatives near Carson's former home of Franklin, to provide her with an education. That summer he met John C. Frémont on a Missouri River steamboat. Frémont was preparing to lead his first expedition and was looking for a guide to take him to South Pass on the Continental Divide. As the two men became acquainted, Carson offered his services, as he had spent much time in the area. The five month journey, made with 25 men, was a success, and Fremont's report was published by Congress. His report "touched off a wave of wagon caravans filled with hopeful emigrants" heading West.

Frémont's success in the first expedition led to his second expedition, undertaken in the summer of 1843. He proposed to map and describe the second half of the Oregon Trail, from South Pass to the Columbia River. Due to Carson's proven skills as a guide, Fremont invited him to join the second expedition. They traveled along the Great Salt Lake into Oregon. They determined that all the land in the Great Basin (centered on modern day Nevada) was land locked, which contributed greatly to the understanding of North American geography at the time. Farther west, they came within sight of Mount Rainier, Mount Saint Helens., and Mount Hood.

One goal of the expedition had been to locate the Buenaventura River, what was believed to be a major east - west river connecting the Continental Divide with the Pacific Ocean. Though its existence was accepted as scientific fact at the time, it was not to be found. Frémont's second expedition established that the river was a fable.

When the expedition ventured into California, they crossed into Mexican territory. The second expedition became snowbound in the Sierra Nevadas that winter. Carson's wilderness skills averted mass starvation. Food was so scarce that their mules "ate one another's tails and the leather of the pack saddles."

The expedition moved south into the Mojave Desert, enduring attacks by Natives, who killed one man. The threat of military intervention by Mexico sent Fremont's expedition southeast, into Nevada, to a watering hole known as Las Vegas. Carson remembered their arrival as follows:

- Our adventures in the desert were eventually terminated by our arrival at "Las Vegas de Santa Clara", and a pleasant thing it was to look once more upon green grass and sweet water, and to reflect that the dreariest part of our journey lay behind us, so that the sands and jornados of the Great Basin would weary our animals no more... The [n]oise of running water, the large grassy meadows, from which the spot takes its name, and the green hills which circle it round – all seem to captivate the eye and please the senses of the well - worn "voyageur".

The party traveled on to Bent's Fort. By August 1844 they returned to Washington, over a year after their departure. Congress published Fremont's report on his expedition in 1845. It added to the national reputations of the two frontiersmen.

Along the route, Frémont and party came across a Mexican man and a boy who had survived an ambush by a band of Natives. They had killed two men, staked two women to the ground and mutilated them, and stolen 30 horses. Carson and fellow mountain man Alex Godey took pity on the two survivors. They tracked the Native band for two days, and upon locating them, rushed into their encampment. They killed two Native Americans, scattered the rest, and returned to the Mexicans with the horses.

- "More than any other single factor or incident, [the Mojave Desert incident] from Frémont's second expedition report is where the Kit Carson legend was born ..."

On June 1, 1845, John Frémont and 55 men left St. Louis, with Carson as guide, on the third expedition. The stated goal was to "map the source of the Arkansas River", on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. But upon reaching the Arkansas, Frémont suddenly made a hasty trail straight to California, without explanation. Arriving in the Sacramento Valley in early winter 1846, he sought to stir up patriotic enthusiasm among the United States immigrants there. He promised that if war with Mexico started, his military force would "be there to protect them." Frémont nearly provoked a battle with Mexican General José Castro near Monterey, California. Castro's troops so outnumbered the US expedition that they could likely have destroyed it. Frémont fled Mexican - controlled California, and went north to Oregon, making camp at Klamath Lake.

On the night of May 9, 1846, Frémont received a courier, Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie, bringing messages from President James Polk. Reviewing the messages, Frémont neglected the customary measure of posting a watchman for the camp. The neglect of this action is said to have been troubling to Carson, yet he had "apprehended no danger". Later that night Carson was awakened by the sound of a thump. Jumping up, he saw his friend and fellow trapper Basil Lajeunesse sprawled in blood. He sounded an alarm and immediately the camp realized they were under attack by Native Americans, estimated to be several dozen in number. By the time the assailants were beaten off, two other members of Frémont's group were dead. The one dead attacker was judged to be a Klamath Lake native. Frémont's group fell into "an angry gloom." Carson was furious and smashed the dead warrior's face into a pulp.

To avenge the deaths, Frémont attacked a Klamath Tribe fishing village named Dokdokwas, that most likely had nothing to do with the attack, at the junction of the Williamson River and Klamath Lake, on May 10, 1846. Accounts by scholars vary, but they agree that the attack completely destroyed the village structures; Sides reports the expedition killed women and children as well as warriors. Later that day, Carson was nearly killed by a Klamath warrior when his gun misfired as the warrior drew a poison arrow. Frémont trampled the warrior with his horse and saved Carson's life.

- "The tragedy of Dokdokwas is deepened by the fact that most scholars now agree that Frémont and Carson, in their blind vindictiveness, probably chose the wrong tribe to lash out against: In all likelihood the band of native Americans that had killed [Frémont's three men] were from the neighboring Modoc... The Klamaths were culturally related to the Modocs, but the two tribes were bitter enemies."

Turning south from Klamath Lake, Frémont led his expedition back down the Sacramento Valley, and promoted the Bear Flag Revolt, an insurrection of United States immigrant settlers. He took charge of it once it had adequately developed. When a group of Mexicans murdered two American rebels, Frémont imprisoned José de los Santos Berreyesa, the alcalde, or mayor of Sonoma, two other Berreyesa brothers, and others he believed were involved.

On June 28, 1846, Berreyesa's father, José de los Reyes Berreyesa, an elderly man, crossed the San Francisco Bay and landed near the area known as San Quentin with two cousins, twin sons of Francisco de Haro, who were 19 years old, to visit his own sons in jail. According to Frémont they were carrying Mexican military dispatches. The men were captured by Carson and his companions when they disembarked. Carson rode to where Frémont was and inquired as to what should be done with the prisoners. Frémont ordered their execution stating, "I want no prisoners, Mr. Carson, do your duty." The men were shot. Afterwards the soldiers robbed them of their belongings and left them naked along the shore. Later, Carson told Jasper O'Farrell that he regretted killing the men, but that the act was only one such that Frémont ordered him to commit.

Frémont's California Battalion next moved south to the Mexican provincial capital of Monterey, where they met US Commodore Robert Stockton in mid July 1846. Stockton had sailed into harbor with two American warships and laid claim to Monterey for the United States. Learning that war with Mexico was underway, Stockton made plans to capture Los Angeles and San Diego and to proceed on to Mexico City. He joined forces with Frémont, and made Carson a lieutenant, thus initiating Carson's military career.

Frémont's unit arrived in San Diego on one of Stockton's ships on July 29, 1846, and took over the town without resistance. Stockton, on a separate warship, claimed Santa Barbara a few days later (Mission Santa Barbara and Presidio of Santa Barbara). Meeting up and joining forces in San Diego, the men marched to Los Angeles and claimed the town without any challenge. On August 17, 1846, Stockton declared California to be United States territory. The following day, August 18, Stephen W. Kearny rode into Santa Fe, New Mexico, with his Army of the West and declared the New Mexican territory conquered.

Stockton and Frémont wanted to announce the conquest of California to President Polk. They asked Carson to carry their correspondence overland to the President. Carson accepted the mission, and pledged to cross the continent within 60 days. He left Los Angeles with 15 European - American men and six Delaware natives on September 5.

Thirty - one days later on October 6, Carson chanced to meet Kearny and his 300 dragoons at the deserted village of Valverde. Kearny had orders from the Polk Administration to subdue both New Mexico and California, and to set up governments there. Learning that California was already conquered, he sent 200 of his men back to Santa Fe, and ordered Carson to guide him back to California to stabilize the situation there. Kearny sent the mail on to Washington by another courier.

For the next six weeks, Lt. Carson guided Kearny and the 100 dragoons west along the Gila River over rugged terrain, arriving at the Colorado River on November 25. On some parts of the trail, mules died at a rate of almost 12 a day. By December 5, three months after leaving Los Angeles, Carson had brought Kearny's men to within 25 miles (40 km) of their destination San Diego.

A Mexican courier was captured en route to Sonora, Mexico, carrying letters to General Jose Castro that reported a Mexican revolt that had retaken California from Commodore Stockton. All the coastal cities were back under Mexican control except San Diego, where the Mexicans had Stockton pinned down and under siege. Kearny and his forces were in danger, as his men were reduced in number and exhausted from the trek from New Mexico. They had to come out of the Gila River trail and confront the Mexican forces, or risk perishing in the desert.

While approaching San Diego, Kearny sent a rancher ahead to notify Commodore Stockton of his presence. The rancher, Edward Stokes, returned with 39 American troops and information that several hundred Mexican dragoons under Capt. Andres Pico were camped at the indigenous village of San Pasqual, between Kearny and Stockton. Kearny decided to raid Pico to capture fresh horses, and sent out a scouting party on the night of December 5–6.

The scouting party set off a barking dog in San Pasqual, and Captain Pico's troops were aroused from their sleep. Having been detected, Kearny decided to attack, and organized his troops to advance on San Pasqual. A complex battle evolved. Twenty - one Americans were killed. By the end of the second day, December 7, the Americans were nearly out of food and water, low on ammunition and weak from the journey along the Gila River. They faced starvation and possible annihilation by the superior numbers of Mexican troops. Kearny ordered his men to dig in on top of a small hill.

Kearny sent Carson and two other men to slip through the siege and get reinforcements. Carson, Edward Beale and a Native American left on the night of December 8 for San Diego, 25 miles (40 km) away. They left their canteens to avoid noise. Their boots also made too much noise, therefore Carson and Beale removed them and tucked them under their belts. They lost their boots, and had to make the journey barefoot through desert, rock and cactus.

By December 10, Kearny believed all hope was gone, and planned to attempt a breakout the next morning. That night 200 American troops on fresh horses arrived, and the Mexican army dispersed in the face of the superior American forces. Kearny arrived in San Diego by December 12. His arrival contributed to the prompt reconquest of California by the American forces.

Following the recapture of Los Angeles in 1846, Stockton appointed Frémont as Governor of California. Frémont sent Carson to carry messages back to Washington, D.C. He stopped in St. Louis and met with Senator Thomas Benton, a prominent supporter of settling of the West and a proponent of Manifest Destiny. He had been instrumental in getting Frémont's expedition reports published by Congress. Once in Washington, Carson delivered his messages to Secretary of State James Buchanan, and had meetings with Secretary of War William Marcy and President James Polk. The president also proposed Carson as a lieutenant in the mounted rifle regiment, but the United States Senate rejected the appointment.

The Navajo raided Socorro, New Mexico, near the end of September, 1846. General Kearny, passing nearby on his way to California after his recent conquest of Santa Fe, learned of the raid and sent a note to Col. William Doniphan, his second - in - command in Santa Fe. He ordered Doniphan to send a regiment of soldiers into Navajo country and secure a peace treaty with them.

A detachment of 30 men made contact with the Navajo and spoke to the Navajo Chief Narbona in mid October, about the same time that Carson met Gen. Kearny on the trail to California. A second meeting between Chief Narbona and Col. Doniphan occurred several weeks later. Doniphan informed the Navajo that all their land now belonged to the United States, and the Navajo and New Mexicans were the “children of the United States” . The Navajo signed a treaty, known as the Bear Spring Treaty, on November 21, 1846. The treaty forbade the Navajo to raid or make war on the New Mexicans, but allowed the New Mexicans to make war on the Navajo if they saw fit.

Despite the treaty, the Navajo continued raiding in New Mexico, which they considered a category separate from war, as did the Jicarilla Apache, Mescalero Apache, Ute, Comanche, and Kiowa. On August 16, 1849 the US Army began an expedition into the heart of Navajo country on an organized reconnaissance to impress the Navajo with the might of the U.S. military. They also mapped the terrain and planned forts. Col. John Washington, the military governor of New Mexico at the time, led the expedition. Forces included nearly 1000 infantry (U.S. and New Mexican volunteers), hundreds of horses and mules, a supply train, 55 Pueblo scouts, and four artillery guns.

On August 29 – 30, 1849, Washington's expedition needed water, and began pillaging Navajo cornfields. Mounted Navajo warriors darted back and forth around Washington's troops to push them off. Washington reasoned he could pillage Navajo crops because the Navajo would have to reimburse the U.S. government for the cost of the expedition. Washington still suggested to the Navajo that in spite of the hostile situation, they and the whites could “still be friends if the Navajo came with their chiefs the next day and signed a treaty”. This is what they did.

The next day Chief Narbona came to “talk peace”, along with several other headmen. After reaching an accord, a scuffle broke out when a New Mexican thought he saw his stolen horse and tried to claim it from the Navajo. (The Navajo held that the horse had passed through several owners by this time, and rightfully belonged to its Navajo owner). Washington sided with the New Mexican. Since the Navajo owner took his horse and fled the scene, Washington told the New Mexican to pick out any Navajo horse he wanted. The rest of the Navajo also left. At this, Col. Washington ordered his soldiers to fire.

Seven Navajo were killed in the volleys; the rest ran and could not be caught. One of the dying was Chief Narbona, who was scalped as he lay dying by a New Mexican souvenir hunter. This massacre prompted the warlike Navajo leaders such as Manuelito to gain influence over those who were advocates of peace.

By the end of the Frémont expeditions and California rebellion, Carson decided to settle down with Joséfa. In 1849 they moved to Taos to take up ranching and farming. However, a peaceful life at home was not to be.

Carson's public image as a hero had been sealed by the Frémont expedition reports of 1845. In 1849 the first of many Carson action novels appeared. Written by Charles Averill, it bore the name Kit Carson: The Prince of the Gold Hunters. This type of western pulp fiction was known as “blood and thunders”. In Averill's novel, Carson finds a kidnapped girl and rescues her, after having vowed to her distraught parents in Boston that he would scour the American West until she was found.

In November 1849, Carson and Major William Grier found the camp of the Jicarilla Apaches who had captured Mrs. Ann White and her daughter. The Jicarilla had attacked the White home and had killed her husband and others. Knowing the soldiers were near, the Jicarilla killed Mrs. White. While picking through the belongings that the Jicarilla had left in their camp, one of Major Grier's soldiers came across a book that the White family had carried with them from Missouri — the paperback novel starring Kit Carson. This was the first time that Carson had come in contact with his own myth.

The episode of the White family killings haunted Carson's memory for many years. He wrote in his autobiography:

- I have much regretted the failure of the attempt to save the life of so esteemed and respected a lady. In the camp was found a book, the first of the kind I had ever seen, in which I was made a great hero, slaying Indians by the hundred, and I have often thought that as Mrs. White would read the same and knowing that I lived near, she would pray for my appearance and that she might be saved.

Later, when a friend offered Averill's book as a gift, Carson told the friend he would rather “burn the damn thing.” In fact, these extravagant novels set the public's view of Carson for a generation. Near the end of his life, Carson met a man from Arkansas. He recounted the incident later:

- “I say, stranger, are you Kit Carson?” the man asked. Carson said yes. “Look ’ere,” the Arkansan replied, casting his eye over Carson’s diminutive frame. “You ain’t the kind of Kit Carson I’m looking for.”

Following the March 30, 1854 battle of Cieneguilla, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke of the Second Regiment of Dragoons organized an expedition to pursue the Jicarilla. With the help of scouts led by Kit Carson, he caught and defeated them April 4, at the canyon of Ojo Caliente.

On January 22, 1858, Kit Carson concluded a treaty of peace between the Muatche Utah, the Arapaho, and the Pueblo of Taos. They agreed to support the United States in the event of any issue between them and the people of any Territory, and to do what they could to suppress rebellion in Utah. At one time the U.S. feared that the Muatche Utah were in alliance with the Mormons.

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, Kit Carson resigned his post as federal Indian agent for northern New Mexico. He joined the New Mexico volunteer infantry organized by Ceran St. Vrain. Although New Mexico Territory officially allowed slavery, geography and economics made the institution so impractical that there were few slaves within its boundaries. The territorial government and the leaders of opinion all threw their support to the Union.

Overall command of Union forces in the Department of New Mexico fell to Colonel Edward R.S. Canby of the Regular Army’s 19th Infantry, headquartered at Ft. Marcy in Santa Fe. Carson, with the rank of Colonel of Volunteers, commanded the third of five columns in Canby’s force. Carson’s command was divided into two battalions, each made up of four companies of the First New Mexico Volunteers, in all some 500 men.

Early in 1862, Confederate forces in Texas under General Henry Hopkins Sibley invaded New Mexico Territory. They aimed to conquer the rich Colorado gold fields and to redirect the resource from the North to the South.

Advancing up the Rio Grande, Sibley’s command clashed with Canby’s Union force at Valverde on February 21, 1862. The day long Battle of Valverde ended when the Confederates captured a Union battery of six guns and forced the rest of Canby’s troops across the river. The Union lost 68 killed and 160 wounded. Colonel Carson’s column spent the morning on the west side of the river out of the action, but at 1 p.m., Canby ordered them to cross. Carson’s battalions fought until ordered to retreat. Carson lost one man killed and one wounded. Colonel Canby had little or no confidence in the hastily recruited, untrained New Mexico volunteers, “who would not obey orders or obeyed them too late to be of any service.” However, Canby did remark about Carson and his volunteer’s “zeal and energy”.

After the battle at Valverde, Colonel Canby and most of the regular troops were ordered to the eastern front. Carson and his New Mexico Volunteers were fully occupied by “Indian troubles”.

Outlaw Navajos (called ladrones, Spanish for thieves), as well as other Native Americans, and their neighboring New Mexicans, had raided, killed and enslaved each other since they had lived side by side during Spanish rule. A lull had taken place in the 1850s under the jurisdiction of Captain Henry Kendrick, commandant of Fort Defiance in northeast Arizona, and Henry Dodge, the government agent. But after Dodge disappeared in late 1856, and Kendrick was transferred to another post, the raids resumed. With the withdrawal of many troops at the start of the Civil War, New Mexicans became more outspoken and demanded that something be done.

Col. Canby devised a plan for the removal of the Navajo to a distant reservation and sent his plans to his superiors in Washington, D.C. But he was promoted to general and recalled east for other duties.

His replacement as commander of the Federal District of New Mexico was Brigadier General James H. Carleton. Carleton believed that the Navajo conflict was the reason for New Mexico's "depressing backwardness". He turned to Kit Carson to help him fulfill his plans of upgrading New Mexico and advancing his own career, as Carson's national reputation had boosted the careers of a series of military commanders who had employed him.

Carleton saw a way to harness the anxieties that had been stirred up [in New Mexico] by the Confederate invasion and the still hovering fear that the Texans might return. If the territory was already on a war footing, the whole society alert and inflamed, then why not direct all this ramped up energy toward something useful? Carleton immediately declared a state of martial law, with curfews and mandatory passports for travel, and then brought all his newly streamlined authority to bear on cleaning up the Navajo mess. With a focus that bordered on obsession, he was determined finally to make good on Kearny's old promise that the United States would "correct all this".

Carleton believed there was gold in the Navajo country, and that they should be driven out to allow its development. The immediate prelude to Carleton's Navajo campaign was to force the Mescalero Apache to Bosque Redondo. Carleton ordered Carson to kill all the men of that tribe, and say that he (Carson) had been sent to "punish them for their treachery and crimes."

Carson was appalled by this brutal attitude and refused to obey it. He accepted the surrender of more than a hundred Mescalero warriors who sought refuge with him. Nonetheless, he completed his campaign in a month.

When Carson learned that Carleton intended him to pursue the Navajo, he sent Carleton a letter of resignation dated February 3, 1863. Carleton refused to accept this and used the force of his personality to maintain Carson's cooperation. In language similar to his description of the Mescalero Apache, Carleton ordered Carson to lead an expedition against the Navajo, and to say to them, "You have deceived us too often, and robbed and murdered our people too long, to trust you again at large in your own country. This war shall be pursued against you if it takes years, now that we have begun, until you cease to exist or move. There can be no other talk on the subject." However, it was largely Canby's proposed plan, written from a position of relative neutrality and created in hopes of defusing the situation, that Carleton and Carson ultimately carried out.

Under Carleton's direction, Carson instituted a scorched earth policy, which coerced the Navajo to surrender. Most corn fields were used to feed his horses, and some fields were destroyed. Carleton had insisted that livestock was not to be used for personal use. To carry out his orders, Carson asked that the government recruit Utes to assist him. He did not personally cut down the orchards; he was aided by other Native American tribes with long standing enmity toward the Navajos. Carson was pleased with the work the Utes did for him, but they went home early in the campaign when told they could not confiscate Navajo booty.

Carson had difficulty with New Mexico volunteers as well. Officers typically came from the ranks of Anglos in the territory, and were not of the best calibre. Carson urged Carleton to accept two resignations he was forwarding, “as I do not wish to have any officer in my command who is not contented or willing to put up with as much inconvenience and privations for the success of the expedition as I undergo myself”.

Unlike the battles in the Civil War, the campaign did not consist of head - to - head battles. Instead, Carson fought when necessary, to round up and take prisoner all the Navajo he could find, to force them to go to Bosque Redondo, also called Fort Sumner.

Finally, in January 1864, after long resisting the plan, Carson sent a company into Canyon de Chelly to investigate the last Navajo stronghold, presuming them to be under the leadership of Manuelito. Carson had feared a trap. But Carleton's orders proved to be effective, and the Navajo realized they had only two choices: surrender and go to Bosque Redondo, or die. By the spring of 1864, 8,000 Navajo men, women and children were forced to march or ride in wagons 300 miles (480 km) from Fort Canby to Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Navajos call this “The Long Walk”.

Carson had left the Army and returned home before the march began, but some Navajo held him responsible for the events. He had promised that those who surrendered would not be harmed, and indeed, they were not attacked directly, but the journey was hard on the people, as they were already starving and poorly clothed, and the provisions were scanty. An estimated 300 Navajo died along the way. Many more died during the next four years on the encampment at Fort Sumner. Carleton had underestimated the number of Navajo that would arrive at Sumner, and also had ordered insufficient provisions, a factor that Carson deplored.

In 1868, after signing a treaty with the US government, the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland. Since then the Navajo Reservation has been enlarged several times to its current size. Thousands of other Navajo who had been living in the wilderness returned to the Navajo homeland centered around Canyon de Chelly.

In November 1864, Carson was sent by General Carleton to deal with the Indians in western Texas. Carson and his 400 troopers and Indian scouts met a combined force of Kiowa, Comanche, and Plains Apache numbering as much as 1,500 at the ruins of Adobe Walls, Texas. In the Battle of Adobe Walls, the Indian force led by Dohäsan made several assaults on Carson's forces which were supported by two mountain howitzers. Carson retreated after burning a Kiowa village. Carson lost the battle, but most authorities give him credit for a skillful defense and a wise decision to withdraw when confronted by numerically superior Indian army.

A few days later, Colonel John M. Chivington led U.S. troops in a massacre at Sand Creek. Chivington boasted that he had surpassed Carson and would soon be known as the great Indian killer. Carson expressed outrage at the massacre and openly denounced Chivington's actions.

The Southern Plains campaign led the Comanches to sign the Little Rock Treaty of 1865. In October 1865, General Carleton recommended that Carson be awarded the brevet rank of brigadier general, "for gallantry in the battle of Valverde, and for distinguished conduct and gallantry in the wars against the Mescalero Apaches and against the Navajo natives of New Mexico".

When the Civil War ended, and the Indian Wars campaigns were in a lull, Carson was breveted a General and appointed commandant of Ft. Garland, Colorado, the heart of Ute country. Carson had many Ute friends in the area and assisted in government relations. He was interviewed there by Wm. T. Sherman. A description of that meeting is included in the Charles Burdett book Life of Kit Carson. After being mustered out of the Army, Carson took up ranching, settling at Boggsville in Bent County. In late 1867 he personally escorted four Ute chiefs to Washington D.C. to visit the President and seek additional government assistance. Soon after his return, his wife Josefa ("Josephine") died from complications after giving birth to their eighth child.

Carson died a month later at age 58 on May 23, 1868, in the presence of Dr. Tilton. Dr. Tilton's description of Carson's last days are included in J.S.C. Abbott's Life of Kit Carson. He died from an abdominal aortic aneurysm in the surgeon's quarters in Fort Lyon, Colorado, located east of Las Animas. He was buried in Taos, New Mexico, next to his wife. His headstone inscription reads: "Kit Carson / Died May 23, 1868 / Aged 59 Years."

His last words were: "Adios Compadres" (Spanish for "Goodbye friends").

Many general accounts of Kit Carson describe him as an outstanding honorable person. Albert Richardson, who knew him personally in the 1850s, wrote that Kit Carson was "a gentleman by instinct, upright, pure, and simple - hearted, beloved alike by Indians, Mexicans and Americans".

Oscar Lipps also presented a positive image of Carson in 1909: "The name of Kit Carson is to this day held in reverence by all the old members of the Navajo tribe. They say he knew how to be just and considerate as well as how to fight the Indians".

Carson's contributions to western history have been reexamined by historians, journalists and Native American activists since the 1960s. In 1968, Carson biographer Harvey L. Carter stated:

- In respect to his actual exploits and his actual character, however, Carson was not overrated. If history has to single out one person from among the Mountain Men to receive the admiration of later generations, Carson is the best choice. He had far more of the good qualities and fewer of the bad qualities than anyone else in that varied lot of individuals.

Some journalists and authors during the last 25 years presented an alternative view of Kit Carson. For instance, Virginia Hopkins stated in 1988 that "Kit Carson was directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of thousands of Indians". Tom Dunlay wrote in 2000 that Carson was directly responsible for the deaths of at least fifty indigenous people. Dunlay portrays Carson as a man with divided loyalties whose beliefs and prejudices were shaped by his times.

In 1970, Lawrence Kelly noted that Carleton had warned 18 Navajo chiefs that all Navajo peoples "must come in and go to the 'Bosque Redondo' where they would be fed and protected until the war was over. That unless they were willing to do this they would be considered hostile."

On January 19, 2006, Marley Shebala, senior news reporter and photographer for Navajo Times, quoted the Fort Defiance Chapter of the Navajo Nation as saying, "Carson ordered his soldiers to shoot any Navajo, including women and children, on sight." This view of Carson's actions may be taken from General James Carleton’s orders to Carson on October 12, 1862, concerning the Mescalero Apaches: "All Indian men of that tribe are to be killed whenever and wherever you can find them: the women and children will not be harmed, but you will take them prisoners and feed them at Ft. Stanton until you receive other instructions".

Sides said that Carson believed the Native Americans needed reservations as a way of physically separating and shielding them from white hostility and white culture. Carson believed most of the Indian troubles in the West were caused by "aggressions on the part of whites." He is said to have viewed the raids on white settlements as driven by desperation, "committed from absolute necessity when in a starving condition." Native American hunting grounds were disappearing as waves of white settlers filled the region.

In 1868, at the urging of Washington and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Carson journeyed to Washington D.C. where he escorted several Ute Chiefs to meet with the President of the United States to plead for assistance to their tribe.

At least 25 titles were recorded, from Kit Carson, Prince of the Gold Hunters (1849) through Kit Carson, King of Scouts (1923). Kit Carson is included in a number of 20th century novels and pulp magazine stories: Comanche Chaser by Dane Coolidge, On Sweet Water Trail by Sabra Conner, On to Oregon by H.W. Morrow, The Pioneers by C.R. Cooper, The Long Trail by J. Allan Dunn and Peltry by A.D.H. Smith.

In Willa Cather's novel Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), the legend of Kit Carson is explored, first as compassionate friend to the natives, later as "misguided" soldier.

William Saroyan's Pulitzer Prize winning play The Time of Your Life (1939) includes a colorful character, an old man, based on the image and reputation of Kit Carson.

Kit Carson also appears in Flashman and the Redskins (1982) by George MacDonald Fraser.

Carson appears as a supporting character in the The Berrybender Narratives (2002 – 2004), a series of four novels by Larry McMurtry.

Four silent films were made featuring Kit Carson as the "star" from 1903 to 1928. From 1933 - 1947 Hollywood produced three talking films: Fighting with Kit Carson, a serial (1933), revised as a single movie: The Return of Kit Carson (1947); Overland with Kit Carson (1939); and Kit Carson (1940), starring Jon Hall in the title role. Disney released Kit Carson and the Mountain Men in 1977.

A fictional western television series, The Adventures of Kit Carson, starring Bill Williams and Don Diamond, ran in syndication from 1951 - 1955. Dream West was a TV 1986 docudrama that includes Kit Carson and John C. Fremont as characters. The History Channel produced Carson and Cody, the Hunter Heroes in 2003. In 2008 PBS/The American Experience produced Kit Carson, a film biography.

Equestrian statues of Carson can be found in Denver, Colorado (by Frederick William MacMonnies, 1911) and in Trinidad, Colorado (by Augustus Lukeman and Frederick Roth, 1912).

The Canadian singer - songwriter, Bruce Cockburn, has a track entitled "Kit Carson" on his 1991 album Nothing But a Burning Light that does not present Carson in a positive light.

The Kit Carson House in Taos, New Mexico, is a U.S. designated National Historic Landmark. It is operated as a museum.

The Kit Carson Museum in Las Animas, Colorado, is located in an adobe building that was built in 1940 to hold German prisoners of war captured in North Africa during World War II. The museum houses artifacts relating to Bent County, Colorado, covering the period from the days of Kit Carson, through World War II. It was scheduled to move into a new facility, once completed.

Fort Garland, located within the city of the same name in Colorado, was the location where Kit Carson briefly relocated his family while he served as commandant of a company of roughly 100 New Mexico Volunteers in 1866 - 1867. It includes original adobe buildings that house a reconstruction of Carson's commandant quarters. The site is a U.S. designated National Historic Landmark, and is operated as the "Fort Garland Museum".

The Kit Carson Chapel, located in Fort Lyon, Colorado, was constructed from the stones of the surgeons' quarters where he died. It is open to the public.

In Rayado, NM, the Kit Carson Museum is operated as a living museum, staffed by nearby Philmont Scout Ranch interpreters.

San Pasqual Battlefield State Historic Park, located near Escondido, California, is a California State Park which honors the memory of the participants from both the United States and Mexico, including Kit Carson, who contested the Battle of San Pasqual on December 5–6, 1846 during the Mexican - American War. The State Park includes a visitor's center that in addition to housing exhibits and a film about the battle, also includes information about the cultural history of the San Pasqual Valley. The State Park also hosts living history presentations, which once a year in December includes a recreation of the battle itself.