<Back to Index>

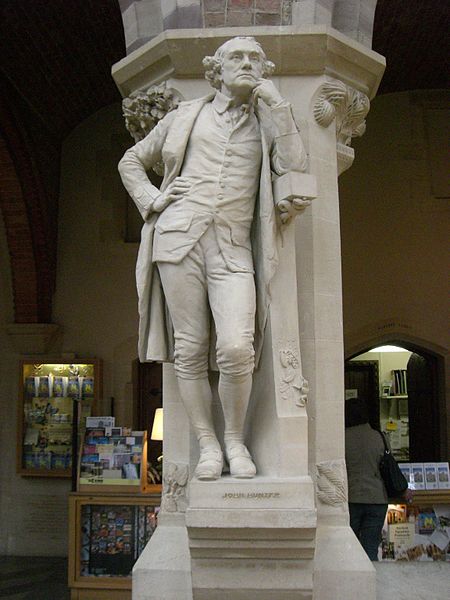

- Surgeon John Hunter, 1728

- Farmer Benjamin Jesty, 1736

PAGE SPONSOR

John Hunter FRS (13 February 1728 – 16 October 1793) was a Scottish surgeon regarded as one of the most distinguished scientists and surgeons of his day. He was an early advocate of careful observation and scientific method in medicine. The Hunterian Society of London was named in his honor. He was the husband of Anne Hunter, a teacher and friend of, and collaborator with, Edward Jenner, the inventor of the smallpox vaccine.

Hunter was born at Long Calderwood, now part of East Kilbride, Lanarkshire, Scotland, the youngest of ten children. The date of his birth is uncertain. Robert Chamber's "Book of Days" (1868) gives an alternate birth date of 14 July, and Hunter is recorded as always celebrating his birthday on the 14th rather than the 13 July shown in the parish register of the town of his birth. Family papers cite his birthday as being variously on the 7th and the 9 February. Three of Hunter's siblings (one of which had also been named John) had died of illness before John Hunter was born. An elder brother was William Hunter, the anatomist. As a youth, John showed little talent, and helped his brother - in - law as a cabinet maker.

In 1771 he married Anne Home, daughter of Robert Boyne Home and sister of Sir Everard Home. They had four children, two of whom died before the age of 5 and one of whom, Agnes (their fourth child), married General Sir James Campbell of Inverneill. In 1791, when Joseph Haydn was visiting London for a series of concerts, Hunter offered to perform an operation for the removal of a large nasal polyp which was troubling the great Austrian composer. According to one account, "Haydn, on his visit to London in 1791, [wrote] folksong arrangements, including The Ash Grove, set to words by Mrs Hunter. Haydn had designs on Mrs Hunter. Her husband ... had designs on Haydn’s famous nasal polyp. Both were refused."

His death in 1793 followed a heart attack during an argument at St George's Hospital over the admission of students.

When nearly 21 he visited William in London, where his brother had become an admired teacher of anatomy. John started as his assistant in dissections (1748), and was soon running the practical classes on his own. It has recently been alleged that Hunter's brother William, and his brother's former tutor William Smellie, were responsible for the deaths of many women whose corpses were used for their studies on pregnancy. John is alleged to have been connected to these murders, since at the time he was acting as William's assistant. However, persons who have studied life in 18th century London agree that the number of gravid women who died in London during the years of Hunter's and Smellie's work was not particularly high for that locality and time; the prevalence of pre-eclampsia, a common condition affecting ten percent of all pregnancies and one easily treated today, but for which there was no treatment in Hunter's time, would more than suffice to explain a mortality rate that seems suspiciously high to 21st century readers. In The Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures, published in 1774, Hunter provides case histories for at least four of the subjects illustrated.

Hunter studied under William Cheselden at Chelsea Hospital and Percival Pott at St. Bartholomew's Hospital. After qualifying he became Assistant Surgeon (house surgeon) at St George's Hospital (1756) and Surgeon (1768).

He was commissioned as an Army surgeon in 1760 and was staff surgeon on expedition to the French island of Belle Île in 1761, then served in 1762 with the British Army in the expedition to Portugal. Contrary to prevailing medical opinion at the time, Hunter was against the practice of 'dilation' of gunshot wounds. This practice, which involved the surgeon deliberately expanding a wound with the aim of making the gunpowder easier to remove. Although sound in theory, in the unsanitary conditions of the time it increased the chance of infection, and Hunter's practice was not to perform dilation 'except when preparatory to something else' such as the removal of bone fragments.

Hunter left the Army in 1763, and spent at least five years working in partnership with James Spence, a well known London dentist. Although not the first person to conduct tooth transplants between living people, he did advance the state of knowledge in this area by realizing that the chances of an (initially, at least) successful tooth transplant would be improved if the donor tooth was as fresh as possible and was matched for size with the recipient. These principles are still used in the transplantation of internal organs. Although donated teeth never properly bonded with the recipients' gums, one of Hunter's patients stated that he had three which lasted for six years, a remarkable period at the time.

Hunter set up his own anatomy school in London in 1764 and started in private surgical practice.

In 1765 he bought a house near the Earl's Court district in London. The house had large grounds which were used to house a collection of animals including 'zebra, Asiatic buffaloes and mountain goats', as well as jackals. (In the house itself, Hunter boiled down the skeletons of some of these animals as part of research on animal anatomy.) A newspaper article reported that many animals that were 'supposed to be hostile to each other but among which, in this new paradise, the greatest friendship prevails', and this image may have been the inspiration for the Doctor Doolittle literary character.

Hunter was elected as Fellow of the Royal Society in 1767. At this time he was considered the authority on venereal diseases. In May 1767, he believed that gonorrhea and syphilis were caused by a single pathogen. Living in an age when physicians frequently experimented on themselves, he inoculated himself with gonorrhea, using a needle that was unknowingly contaminated with syphilis. When he contracted both syphilis and gonorrhea, he claimed it proved his erroneous theory that they were the same underlying venereal disease. He championed its treatment with mercury and cauterization. He included his findings in his Treatise on the Venereal Disease, first issued in 1786. Because of Hunter’s reputation, knowledge concerning the true nature of gonorrhea and syphilis was retarded, and it was not until 51 years later that his theory was proved to be wrong.

In 1768 Hunter was appointed as surgeon to St. George's Hospital. Later he became a member of the Company of Surgeons. In 1776 he was appointed surgeon to King George III.

In 1783 Hunter moved to a large house in Leicester Square, where today there stands a statue to him. The space allowed him to arrange his collection of nearly 14,000 preparations of over 500 species of plants and animals into a teaching museum.

Also in 1783 he acquired the skeleton of the 7' 7" Irish giant Charles Byrne against Byrne's clear deathbed wishes — he had asked to be buried at sea. Hunter bribed a member of the funeral party (possibly for £500) and filled the coffin with rocks at an overnight stop, then subsequently published a scientific description of the anatomy and skeleton. The skeleton today is in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.

In 1786 he was appointed deputy surgeon to the British Army and in 1790 he was made Surgeon General by the then Prime Minister William Pitt. While in this post he instituted a reform of the system for appointment and promotion of army surgeons based on experience and merit, rather than the patronage - based system that had been in place.

In 1799 the government purchased Hunter's collection of papers and specimens, which it presented to the Company of Surgeons. He was an excellent anatomist; his knowledge and skill as a surgeon was based on sound anatomical background. Among his numerous contributions to medical science are:

- study of human teeth;

- extensive study of inflammation;

- fine work on gunshot wounds;

- some work on venereal diseases, in addition to his work following his likely self - experimentation;

- an understanding of the nature of digestion, and verifying that fats are absorbed into the lacteals, a type of small intestine lymphatic capillary, and not into the intestinal blood capillaries as was generally accepted;

- the first complete study of the development of a child;

- proof that the maternal and foetal blood supplies are separate;

- unraveling of one of the major anatomical mysteries of the time – the role of the lymphatic system.

While most of his contemporaries and others since have regarded Hunter as a great anatomist, he undertook anatomy not only because it was practical and allowed for the direct observation of nature in the true Baconian tradition ("his mode of studying nature was … strictly Baconian. Hunter, unlike his contemporaries … sought the reason for each phenomenon), but because it afforded him the opportunity, given his empirical rather than rational bent, to study his main interest - life, in all its forms.

- The scope of Hunter's labors may be defined as the explication of the various phases of life exhibited in organized structures, both animal and vegetable, from the simplest to the most highly differentiated. By him, therefore, comparative anatomy was employed, not in subservience to the classification of living forms, as by Cuvier, but as a means of gaining insight into the principle animating and producing these forms, by virtue of which he perceived that, however different in form and faculty, they were all allied to himself.

Hunter's interest in the question of life puts him in the tradition of Romantic medicine. In what does life consist? is a question which in his writings he frequently considers, and which seems to have been ever present in his mind. Life in living organisms is seen in repair and maintenance (a sustaining power) but also capable of generation and regeneration. Life for Hunter was a principle independent of matter or form, an agency functioning under the control of law in various modes and degrees. It was not reducible to the stimulus of sensation, but also acted independently (Brunonian System of Medicine).

- The living principle, said Hunter, is coeval with the existence of animal or vegetable matter itself, and may long exist without sensation. The principle upon which depends the power of sensation regulates all our external actions, as the principle of life does our internal, and the two act mutually on each other in consequence of changes produced in the brain." (Encyclopedia Britannica 1911)

Hunter also discovered that there exists in animals a latent heat of life, set free in the process of death (Treatise on the Blood, p. 80), and with Harvey, held that blood contained a vitality of its own, 'fire' element. Further, life for Hunter was an interplay between the blood and the body. He even inclined to the hypothesis that chyle has life, and that food becomes " animalized " in digestion.

Hunter held that life went beyond explanation by means of inertial science.

- Mere composition of matter," he remarked, " does not give life; for the dead body has all the composition it ever had; life is a property we do not understand; we can only see the necessary leading steps towards it.

- As from life only, said he in one of his lectures, we can gain an idea of death, so from death only we gain an idea of life. Life, being an agency leading to, but not consisting of, any modification of matter, " either is something superadded to matter, or else consists in a peculiar arrangement of certain fine particles of matter, which being thus disposed acquire the properties of life."

Hunter also differentiated between organic and inorganic growth, such

as in certain crystals. He further held that from the diversity of

fossils and allied living structures, various periods of stability,

lasting thousands of centuries, were interrupted by great climatic

variations. These observations of the fossil record also led him to

conclude that "the origin of species in variation" as Darwin would later

present, was not possible.

- Hunter considered that very few fossils of those that resemble recent forms are identical with them. He conceived that the latter might be varieties, but that if' they are really different species, then " we must suppose that a new creation must have taken place." It would appear, therefore, that the origin of species in variation had not struck him as possible.

As with John Brown, for Hunter pathology was a science of physiology. Dr. Richard Saumarez, who wrote his A New Physiology in 1798, was clearly indebted to Hunter's idea of the living principle and the many facts of observation he brought to bear on its existence.

- Mr. John Hunter … disclaimed the doctrine that ascribed to matter the power of kneading itself into organs, or which vainly supposed that life could ever arise out of death; much less that it could ever be an effect, of which material action was the immediate cause… and … proclaimed the existence of a principle of life, which was the cause (not the effect) of organization and action, and to which it had a prior existence.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a key figure in Romantic thought, science and medicine, was also knowledgeable about Hunter's work and writings and saw in him the seeds of Romantic medicine, namely as regards his principle of life, which he felt had come from the mind of genius.

- WHEN we stand before the bust of John Hunter, or as we enter the magnificent museum furnished by his labors, and pass slowly, with meditative observation through this august temple, which the genius of one great man has raised and dedicated to the wisdom and uniform working of the Creator, we perceive at every step the guidance, we had almost said, the inspiration, of those profound ideas concerning Life, which dawn upon us, indeed, through his written works, but which he has here presented to us in a more perfect language than that of words the language of God himself, as uttered by Nature. That the true idea of Life existed in the mind of John Hunter I do not entertain the least doubt.(Biographia Literaria)

Hunter was the basis for the character "Jack Tearguts" in William Blake's unfinished satirical novel, An Island in the Moon. He is a principal character in Hilary Mantel's 1998 novel, The Giant, O'Brien.

It is possible that his Leicester Square house was the inspiration for the home of Dr Jekyll of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Hunter's house had two entrances, one through which the living area for his family was accessible, and another, leading to a separate street, which provided access to his museum and dissecting rooms. This pattern echoes that of the house in the story, in which the respectable Dr Jekyll used one entrance to the house and Mr Hyde the other, less prominent, one.

A bust of John Hunter stands on a pedestal outside the main entrance to St George's Hospital in Tooting, South London, along with a lion and unicorn taken from the original Hyde Park Corner building. There is also a bust of him in Leicester Square in London's West End and in the South West corner of Lincoln's Inn Fields.

The John Hunter Hospital, the largest hospital in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia, and principal teaching hospital of the University of Newcastle, is named after Hunter (as well as two other historically significant John Hunters).

His birthplace in Long Calderwood, Scotland, has been preserved as Hunter House Museum.

Hunter's character has been discussed by biographers:

To the kindness of his disposition, his fondness for animals, his aversion to operations, his thoughtful and self - sacrificing attention to his patients, and especially his zeal to help forward struggling practitioners and others in any want abundantly testify. Pecuniary means he valued no further than they enabled him to promote his researches; and to the poor, to non - beneficed clergymen, professional authors and artists his services were rendered without remuneration.

His nature was kindly and generous, though outwardly rude and repelling.... Later in life, for some private or personal reason, he picked a quarrel with the brother who had formed him and made a man of him, basing the dissension upon a quibble about priority unworthy of so great an investigator. Yet three years later, he lived to mourn this brother's death in tears.

He had a reputation as a man with a "fiery temper and maverick views".

Hunter claimed that originally the negroid race was white at birth, and that over time because of the sun, they turned black. Hunter also claimed that blisters and burns would likely to turn white on a negro, which he believed was evidence that the negros' original ancestors were white.

Benjamin Jesty (c. 1736 – 16 April 1816) was a farmer at Yetminster in Dorset, England, notable for his early experiment in inducing immunity against smallpox using cowpox.

The notion that those people infected with cowpox, a relatively mild disease, were subsequently protected against smallpox was not an uncommon observation with country folk in the late 18th century, but Jesty was one of the first to intentionally administer the less virulent virus. He was one of the six English, Danish and German people who reportedly administered cowpox to artificially induce immunity against smallpox from 1770 to 1791; only Gloucestershire apothecary and surgeon Dr John Fewster's 1765 paper in the London Medical Society and Jobst Bose of Göttingen, Germany, with his 1769 inoculations pre-dated Jesty's work.

Unlike Edward Jenner, a medical doctor who is given broad credit for developing the smallpox vaccine in 1796, Jesty did not publicize his findings made some twenty years earlier in 1774.

Jesty was born in Yetminster, Dorset, and baptized there on 19 August 1736, the youngest of at least four sons of Robert Jesty, who was a butcher. Little else is known of his early life. In March 1770 he married Elizabeth Notley (1740 – 1824) in Longburton, four miles north - east of Yetminster. The couple lived at Upbury Farm, next to Yetminster churchyard, and the couple had four sons and three daughters.

During the eighteenth century smallpox was widespread throughout England, with frequent epidemics. It was known in the dairy farming areas in the south - west of the country that the milkmaids and other workers who contracted cowpox from handling cows' udders, were afterwards immune to smallpox. Such people were able to nurse smallpox victims without fear of contracting the disease themselves. This folk knowledge gradually became more widely disseminated among the medical community: in 1765 a Dr Fewster (possibly John Fewster) of Thornbury, Gloucestershire, presented a paper to the Medical Society of London entitled "Cow pox and its ability to prevent smallpox", and Dr. Rolph, another Gloucestershire physician, stated that all experienced physicians of the time were aware of this.

Jesty and two of his female servants, Ann Notley and Mary Reade, had been infected with cowpox. When an epidemic of smallpox came to Yetminster in 1774, Jesty decided to try to give his wife Elizabeth and two eldest sons immunity by infecting them with cowpox. He took his family to a cow at a farm in nearby Chetnole that had the disease, and using a darning needle, transferred pustular material from the cow by scratching their arms. The boys had mild local reactions and quickly recovered but his wife's arm became very inflamed and for a time her condition gave cause for concern, although she too recovered fully in time.

Jesty's experiment was met with hostility by his neighbors. He was labelled inhuman, and was "hooted at, reviled and pelted whenever he attended markets in the neighborhood’". The introduction of an animal disease into a human body was thought disgusting and some even "feared their metamorphosis into horned beasts". But the treatment's efficacy was several times demonstrated in the years which followed, when Jesty's two elder sons, exposed to smallpox, failed to catch the disease.

Interest in the prophylactic powers of cowpox virus grew and in May 1796, over 20 years after Jesty had made his inoculations, Edward Jenner began his series of vaccination experiments. In about 1797 Jesty and his family moved from Yetminster, when Jesty took up the tenancy of Downshay Manor Farm in Worth Matravers near the Dorset coast. Here he came to the attention of Dr. Andrew Bell, rector of nearby Swanage who (possibly encouraged by Jesty's efforts) vaccinated over 200 of his practitioners in 1806.

In June 1802 Jenner was given a reward of £10,000 from the House of Commons for discovering and promoting vaccination, and another award of £20,000 followed in 1807. Before this first amount had been awarded, George Pearson, founder of the Original Vaccine Pock Institution, had brought evidence before the House of Commons of Jesty's work in 1774, work which predated Jenner's by 22 years. Unfortunately, Jesty's well documented case was weakened by his failure to petition in person, and Pearson's inclusion of other claimants whose evidence could not be validated, so no reward was forthcoming.

Unaware of George Pearson’s previous petitions to the Pitt Government about the Dorset farmer, the Reverend Dr. Andrew Bell, rector of Swanage near where Jesty later resided, prepared a paper dated 1 August 1803, proposing Jesty as the first vaccinator, and sent copies to the Original Vaccine Pock Institute and the member of parliament, George Rose. Bell wrote to the Institution again in 1804, having learned of Pearson's involvement.

In 1805, at Pearson's instigation and the institution's invitation, Jesty gave his evidence before 12 medical officers of the institution at its base on the corner of Broadwick Street and Poland Street in Soho. Robert, Jesty's oldest son (by then 28 years old) also made the trip to London and agreed to be inoculated with smallpox again to prove that he still had immunity. After Jesty had been cross examined, he was presented with a long testimonial and pair of gold mounted lancets. The verbal evidence of their examination was published in the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal.

Report from the Original Vaccine Pock Institute, 1805 "That he was led to undertake this novel practice in 1774 to counteract the small - pox, at that time prevalent at Yetminster, where he then resided, from knowing the common opinion of the country ever since he was a boy (now 60 years ago) that persons who had gone through the cowpock naturally, ie by taking it from cows, were insusceptible of the small - pox; by himself being incapable of taking the small - pox, having gone through the cow - pock many years before; from knowing many individuals, who, after the cowpock, could not have the small - pox excited; from believing that the cow - pock was an affection free from danger; and from his opinion that, by the cow - pock inoculation, he should avoid ingrafting various diseases of the human constitution, such as "the Evil (scrofula), madnes, lues (syphilis), and many bad humors," as he called them."

For the event, Jesty's family had tried to persuade him to dress in a more up - to - date fashion, but he refused saying that "he did not see why he should dress better in London than in the country". Immediately after his interrogation, Jesty was taken round to the studio of the portrait painter Michael William Sharp in nearby Great Marlborough Street. Jesty proved an impatient sitter, and so Mrs Sharp played the piano to try to soothe him as Sharp painted. After a chequered history, the portrait is now owned by the Wellcome Trust and is on loan to the Dorset County Museum. It was to be shown there from 26 October 2009 to February 2010. The painting would be shown a small display of vaccination equipment.

On Sunday 15 July 1806, Bell preached the same sermon twice in honor of Jesty, "whose discovery of the efficacy of the cowpock against smallpox is so often forgotten by those who have heard of Dr Jenner".

Jesty died in Worth Matravers on 16 April 1816 and was buried in a prominent position in the parish churchyard. His widow, Elizabeth, died on 8 January 1824 and was buried alongside him. Both headstones are listed structures, primarily due to their historic interest. The full text on Jesty's headstone reads:

(Sacred) To the Memory OF Benj.in. Jesty (of Downshay) who departed this Life, April 16th 1816 aged 79 Years. He was born at Yetminster in this County, and was an upright honest Man: particularly noted for having been the first Person (known) that Introduced the Cow Pox by Inoculation, and who from his great strength of mind made the Experiment from the (Cow) on his Wife and two Sons in the Year 1774.