<Back to Index>

This page is sponsored by:

PAGE SPONSOR

Bologna (Emilian: Bulåggna; Latin: Bononia) is the largest city (and the capital) of Emilia - Romagna Region in Northern Italy. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with a rich history, art, cuisine, music, and culture. It is the seventh largest city in terms of population in Italy, heart of a metropolitan area (officially recognized by the Italian Government as a città metropolitana) of about one million people.

The city, the first settlements of which date back to at least one millennium BCE, has always been an important urban center, first under the Etruscans (Velzna / Felsina) and the Celts (Bona), then under the Romans (Bononia), then again in the Middle Ages, as a free municipality (for one century it was the fifth largest European city based on population). Home to the oldest university in the world, University of Bologna, founded in 1088, Bologna hosts thousands of students who enrich the social and cultural life of the city. Famous for its towers and lengthy porticoes, Bologna has a well preserved historical center (one of the largest in Italy) thanks to a careful restoration and conservation policy which began at the end of the 1970s, on the heels of serious damage done by the urban demolition at the end of the 19th century as well as that caused by wars.

An important cultural and artistic center, its importance in terms of landmarks can be attributed to homogeneous mixture of monuments and architectural examples (medieval towers, antique buildings, churches, the layout of its historical center) as well as works of art which are the result of a first class architectural and artistic history. Bologna is also an important transportation crossroad for the roads and trains of Northern Italy, where many important mechanical, electronic and nutritional industries have their headquarters. According to the most recent data gathered by the European Regional Economic Growth Index (E-REGI) of 2009, Bologna is the first Italian city and the 47th European city in terms of its economic growth rate.

Bologna is home to prestigious cultural, economic and political institutions as well as one of the most impressive trade fair districts in Europe. In 2000 it was declared European capital of culture and in 2006, a UNESCO “city of music”. The city of Bologna was selected to participate in the Universal Exposition of Shanghai 2010 together with 45 other cities from around the world. Bologna is also one of the wealthiest cities in Italy, often ranking as one of the top cities in terms of quality of life in the country: in 2011 it ranked 1st out of 107 Italian cities.

The area around Bologna has been inhabited since the 9th century BC, as evidenced by the archeological digs in the 19th century in nearby Villanova. This period, and up to the 6th century, is in fact generally referred to as villanovian, and had various nuclei of people spread out around this area. In the 7-6th centuries BC, Etruria began to have an influence on this area, and the population went from Umbrian to Etruscan. The town was renamed Felsina.

In the 4th century BC, the city and the surrounding area were conquered by the Boii, a Celtic tribe from Transalpine Gaul. The tribe settled down and mixed so well with the Etruscans, after a brief period of aggression, that they created a civilization that modern historians call Gaul - Etruscan (one of the best examples is the archeological complex of Monte Bibele, in the Apennines near Bologna). The Gauls dominated the area until 196 BC, when they were sacked by the Romans. After the Battle of Telamon, in which the forces of the Boii and their allies were badly beaten, the tribe reluctantly accepted the influence of the Roman Republic, but with the outbreak of the Punic Wars the Celts once more went on a war path. They first helped Hannibal's army cross the Alps then they supplied him with a consistent force of infantry that proved itself decisive in several battles. With the downfall of the Carthaginians came the end of the Boii as a free people, the Romans destroyed many settlements and villages (Monte Bibele is one of them) and then founded the colonia of Bononia in c.189 BC. The settlers included three thousand Latin families led by the consul Lucius Valerius Flaccus. The Celtic population was ultimately absorbed into the Roman society but the language has survived in some measure in the Bolognese dialect, which linguists say belongs to the Gallo - Italic group of languages and dialects. The building of the Via Aemilia in 187 BC made Bologna an important center, connected to Arezzo by way of the Via Flaminia minor and to Aquileia through the Via Aemilia Altinate.

In 88 BC, the city became a municipium: it had a rectilinear street plan with six cardi and eight decumani (intersecting streets) which are still discernible today. During the Roman era, its population varied between c. 12,000 to c. 30,000. At its peak, it was the second city of Italy, and one of the most important of all the Empire, with various temples and baths, a theater, and an arena. Pomponius Mela included Bononia among the five opulentissimae ("richest") cities of Italy. Although fire damaged the city during the reign of Claudius, the Roman Emperor Nero rebuilt it in the 1st century AD.

After the fall of the Empire, this area fell under the power of Odoacre, Theodore the Great (493 - 526), Byzantium and finally the Longobards, who used it mostly as a military center. In 774, the city fell to Charlemagne, who gave it to Pope Adrian I.

After a long decline, Bologna was reborn in the 5th century under bishop Petronius. According to legend, St. Petronius built the church of S. Stefano. After the fall of Rome, Bologna was a frontier stronghold of the Exarchate of Ravenna in the Po plain, and was defended by a line of walls which did not enclose most of the ancient ruined Roman city. In 728, the city was captured by the Lombard king Liutprand, becoming part of the Lombard Kingdom. The Germanic conquerors formed a district called "addizione longobarda" near the complex of S. Stefano. Charlemagne stayed in this district in 786.

In the 11th century, Bologna began to aspire to being a free commune, which it was able to do when Matilda of Tuscany died, in 1115, and the following year the city obtained many judicial and economic concessions from Henry V. Bologna joined the Lombard League against Frederick Barbarossa in 1164 which ended with the Peace of Costanza in 1183; after which, the city began to expand rapidly (this is the period in which its famous towers were built) and it became one of the main commercial trade centers thanks to a system of canals that allowed large ships to come and go.

Traditionally said to be founded in 1088, the University of Bologna is widely considered to be the first university. The university originated as an international center of study of medieval Roman law under major linguists, including Irnerius. It numbered Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarca among its students.

In the 12th century, the expanding city needed a new line of walls, and at the end of the 13th century, Bologna had between 50,000 and 60,000 inhabitants making it the fifth largest city in Europe (after Cordova, Paris, Venice and Florence) and tied with Milan as the biggest textile industry area in Italy.

The complex system of canals in Bologna was one of the most advanced waterway systems in Europe, and took its water from the Savena, Aposa and Reno Rivers. The main canals were Canale Navile, Canale di Reno and Canale di Savena. Hydraulic energy derived from the canal system helped run the numerous textile mills and transport goods. Now these canals are located under the city and some can even be visited on organized rafting tours.

In 1256, Bologna promulgated the "Paradise Law", which abolished feudal serfdom and freed the slaves, using public money. At that time the city center was full of towers (perhaps 180), built by the leading families, notable public edifices, churches and abbeys. In the 1270s Bologna's politics was dominated by Luchetto Gattilusio, a Genoese diplomat and man of letters who became the city Governor. Like most Italian cities of that age, Bologna was torn by internal struggles related to the Guelph and Ghibelline factions, which led to the expulsion of the Ghibelline family of the Lambertazzi in 1274.

After this period of great prosperity, Bologna experienced some ups and downs: it was crushed in the Battle of Zappolino by the Modenese in 1325 but then prospered under the rule of Taddeo Pepoli (1337 – 1347). Then in 1348, during the Black Plague, about 30,000 inhabitants died, and it subsequently fell to the Visconti of Milan, but returned to Papal control under Cardinal Gil de Albornoz in 1360. In the following years, Republican governments like that of 1377, which was responsible for the building of the Basilica di San Petronio and the Loggia dei Mercanti, alternated with Papal or Visconti resurgences, while the city's families engaged in continual internecine fighting.

In 1337, the rule of the noble Pepoli family, nicknamed by some scholars as the "underground nobles" as they governed as "the first among equals" rather than as true nobles of the city. This noble family's rule was in many ways an extension of past rules, and resisted until March 28, 1401 when the Bentivoglio family took over. The Bentivoglio family ruled Bologna, first with Sante (1445 – 1462) and then under Giovanni II (1462 – 1506). This period was a flourishing one for the city, with the presence of notable architects and painters who made Bologna a true city of art. During the Renaissance, Bologna was the only Italian city that allowed women to excel in any profession. Women had much more freedom than in other Italian cities; some even had the opportunity to earn a degree at the university. The School of Bologna of painting flourished in Bologna between the 16th and 17th centuries, and rivaled Florence and Rome as the center of painting.

Giovanni's reign ended in 1506 when the Papal troops of Julius II besieged Bologna and sacked the artistic treasures of his palace. From that point on, until the 18th century, Bologna was part of the Papal States, ruled by a cardinal legato and by a Senate which every two months elected a gonfaloniere (judge), assisted by eight elder consuls. In 1530, in front of Saint Petronio Church, Charles V was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII.

Then a plague at the end of the 16th century reduced the population from 72,000 to 59,000, and another in 1630 to 47,000. The population later recovered to a stable 60,000 – 65,000. However, there was also great progress during this era: in 1564, the Piazza del Nettuno and the Palazzo dei Banchi were built, along with the Archiginnasio, the center of the University. The period of Papal rule saw the construction of many churches and other religious establishments, and the reincarnation of older ones. At this time, Bologna had ninety - six convents, more than any other Italian city. Artists working during this period in Bologna established the Bolognese School which includes Annibale Carracci, Domenichino, Guercino and others of European fame.

In 1796, Napoleon took Bologna with his French troops, and with the rise of Napoleon, Bologna became the capital of the short lived Cispadane Republic. After the fall of Napoleon, and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Bologna once again fell under the sovereignty of the Papal States, rising up in 1831 and again in 1849, when it temporarily expelled the Austrian garrisons which controlled the city. After a visit by Pope Pius IX in 1857, on 12 June 1859 the city voted in favor of annexation by the Kingdom of Sardinia, soon to become the Kingdom of Italy.

Bologna was bombed heavily during World War II. The strategic importance of the city as industrial and railway hub connecting northern and central Italy made it a strategic target for the Allied forces. On July 16, 1943 a massive aerial bombardment destroyed much of the historic city center and killed scores of people. The main railway station and adjoining areas were severely hit, and 44% of the buildings in the center were listed as having been destroyed or severely damaged. The city was heavily bombed again on September 25. The raids, which this time were not confined to the city center, left 936 people dead and thousands injured.

During the war, the city was also a key center of the Italian resistance movement. On November 7, 1944, a pitched battle around Porta Lame, waged by partisans of the 7th Brigade of the Gruppi d'Azione Patriottica against Fascist and Nazi occupation forces, did not succeed in triggering a general uprising, despite being one of the largest resistance led urban conflicts in the European theater. Resistance forces entered Bologna on the morning of April 21, 1945. By this time, the Germans had already largely left the city in the face of the Allied advance, spearheaded by Polish forces advancing from the east during the Battle of Bologna which had been since April 9. First to arrive in the center was the 87th Infantry Regiment of the Friuli Combat Group under general Arturo Scattini, who entered the center from Porta Maggiore to the south. Since the soldiers were dressed in British outfits, they were initially thought to be part of the allied forces; when the local inhabitants heard the soldiers were speaking Italian, they poured out on to the streets to celebrate. Polish reconnaissance units of the Polish 2nd Corps entered Bologna from another direction on the same morning as the Friuli Combat Group. The fighting to oust the Germans from the town had been mostly undertaken by Polish troops.

Until the early 19th century, when a large scale urban reconstruction project was undertaken, Bologna remained one of the best preserved walled medieval cities in Europe; to this day it remains unique in its historic value. Despite having suffered considerable bombing damage in 1944, Bologna's 350 acres (141.64 ha) historic center today is Europe's second largest, containing an immense wealth of important Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque artistic monuments.

Bologna developed along the Via Emilia as an Etruscan and later Roman colony; the Via Emilia still runs straight through the city under the changing names of Strada Maggiore, Rizzoli, Ugo Bassi, and San Felice. Due to its Roman heritage, the central streets of Bologna, today largely pedestrianized, follow the grid pattern of the Roman settlement.

The original Roman ramparts were supplanted by a high medieval system of fortifications, remains of which are still visible, and finally by a third and final set of ramparts built in the 13th century, of which numerous sections survive. No more than twenty medieval defensive towers remain out of up to 180 that were built in the 12th and 13th centuries before the arrival of unified civic government. The most famous of the towers of Bologna are the central "two towers" (Asinelli and Garisenda), whose iconic leaning forms provide a popular symbol of the town.

The cityscape is further enriched by elegant and extensive arcades (or porticos), for which the city is famous. In total, there are some 38 kilometers of arcades in the city's historical center (over 45 km in the city proper), which make it possible to walk for long distances sheltered from the elements.

The Portico of San Luca is one of the longest arcades in the world. It connects Porta Saragozza (one of the twelve gates of the ancient walls built in the Middle Ages, which circled a 7.5 km part of the city) with the Sanctuary of the Madonna di San Luca, a church begun in 1723 on the site of an 11th century edifice which had already been enlarged in the 14th century, prominently located on a hill (289 m) overlooking the town, which is one of Bologna's main landmarks. The winding 666 vault arcade, almost four kilometers (3,796 m) long, effectively links San Luca, as the church is commonly called, to the center of town. Its porticos provide shelter for the traditional procession which every year since 1433 has carried a Byzantine icon of the Madonna with Child attributed to Luke the Evangelist down to the cathedral during Ascension week.

Bologna is home to many other notable churches. These include:

- San Petronio Basilica, one of the world's largest

- Bologna Cathedral

- St. Stephen basilica and sanctuary

- St. Dominic basilica and sanctuary

- St. Francis basilica

- Santa Maria dei Servi basilica

- San Giacomo Maggiore basilica (13th - 14th century), featuring numerous Renaissance artworks such as Lorenzo Costa the Elder's Bentivoglio Altarpiece

- San Michele in Bosco

The University of Bologna, founded in 1088, is the oldest existing university in the world, and was an important center of European intellectual life during the Middle Ages, attracting scholars from throughout Christendom. A unique heritage of medieval art, exemplified by the illuminated manuscripts and jurists' tombs produced in the city from the 13th to the 15th century, provides a cultural backdrop to the renown of the medieval institution. The Studium, as it was originally known, began as a loosely organized teaching system with each master collecting fees from students on an individual basis. The location of the early University was thus spread throughout the city, with various colleges being founded to support students of a specific nationality.

In the Napoleonic era, the headquarters of the university were moved to their present location on Via Zamboni (formerly Via San Donato), in the north - eastern sector of the city center. Today, the University's 23 faculties, 68 departments, and 93 libraries are spread across the city and include four subsidiary campuses in nearby Cesena, Forlì, Ravenna and Rimini. Noteworthy students present at the university in centuries past included Dante, Petrarch, Thomas Becket, Pope Nicholas V, Erasmus of Rotterdam, Peter Martyr Vermigli, and Copernicus. Laura Bassi, appointed in 1732, became the first woman to officially teach at a college in Europe. In more recent history, Luigi Galvani, the discoverer of biological electricity, and Guglielmo Marconi, the pioneer of radio technology, also worked at the University. The University of Bologna remains one of the most respected and dynamic post secondary educational institutions in Italy. To this day, Bologna is still very much a university town, and the city's population swells from 400,000 to over 500,000 whenever classes are in session. This community includes a great number of Erasmus, Socrates and overseas students.

The University of Bologna is also the birthplace of the Kappa Sigma Fraternity. It was founded by Manuel Chrysoloras in 1400. The fraternity was formed for mutual protection against Baldassare Cossa, who extorted and robbed the students of the university, and later usurped the papacy under the name John XXIII.

The university's botanical garden, the Orto Botanico dell' Università di Bologna, was established in 1568; it is the fourth oldest in Europe.

The theater was a popular form of entertainment in Bologna until the 16th century. The first public theater was the Teatro alla Scala, active since 1547 in Palazzo del Podestà.

An important figure of Italian Bolognese theater was Alfredo Testoni, the playwright, author of The Cardinal Lambertini, which had great theatrical success since 1905, then repeated on the screen by the Bolognese actor Gino Cervi.

Bologna's opera house is the Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

The Orchestra Mozart, whose music director is Claudio Abbado, was created in 2004.

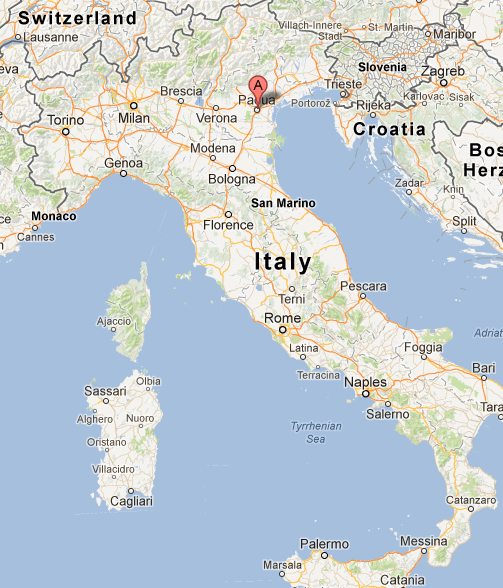

Padua (Italian: Padova, Latin: Patavium, Venetian: Padoa, Ancient German: Esten) is a city and comune in the Veneto, northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Padua and the economic and communications hub of the area. Padua's population is 214,000 (as of 2011). The city is sometimes included, with Venice (Italian Venezia) and Treviso, in the Padua - Treviso - Venice Metropolitan Area, having a population of c. 1,600,000.

Padua stands on the Bacchiglione River, 40 km west of Venice and 29 km southeast of Vicenza. The Brenta River, which once ran through the city, still touches the northern districts. Its agricultural setting is the Venetian Plain (Pianura Veneta). To the city's south west lies the Euganaean Hills, praised by Lucan and Martial, Petrarch, Ugo Foscolo and Shelley.

It hosts the renowned University of Padua, almost 820 years old and famous, among other things, for having had Galileo Galilei among its lecturers.

The city is picturesque, with a dense network of arcade streets opening into large communal piazze, and many bridges crossing the various branches of the Bacchiglione, which once surrounded the ancient walls like a moat.

Padua is the setting for most of the action in Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew.

Padua claims to be the oldest city in northern Italy. According to a tradition dated at least to Virgil's Aeneid, and rediscovered by the medieval commune, it was founded in 1183 BC by the Trojan prince Antenor, who was supposed to have led the people of Eneti or Veneti from Paphlagonia to Italy. The city exhumed a large stone sarcophagus in the year 1274 and declared these to represent Antenor's relics.

Patavium, as Padua was known by the Romans, was inhabited by (Adriatic) Veneti. They were reputed for their excellent breed of horses and the wool of their sheep. Its men fought for the Romans at Cannae. The city was a Roman municipium since 45 BC. It became so powerful that it was reportedly able to raise two hundred thousand fighting men. Abano, which is nearby, is the birthplace of the reputed historian Livy. Padua was also the birthplace of Valerius Flaccus, Asconius Pedianus and Thrasea Paetus.

The area is said to have been Christianized by Saint Prosdocimus. He is venerated as the first bishop of the city.

The history of Padua after Late Antiquity follows the course of events common to most cities of north - eastern Italy. Padua suffered severely from the invasion of the Huns under Attila (452). It then passed under the Gothic kings Odoacer and Theodoric the Great. However during the Gothic War it was reconquered by the (Eastern) Romans in 540. The city was seized again by the Goths under Totila, but was restored to the Eastern Empire by Narses in 568.Then it fell under the control of the Lombards. In 601, the city rose in revolt, against Agilulf, the Lombard king. After suffering a 12 year long and bloody siege, it was stormed and burned by him. The antiquity of Padua was seriously damaged: the remains of an amphitheater (the Arena) and some bridge foundations are all that remain of Roman Padua today. The townspeople fled to the hills and returned to eke out a living among the ruins; the ruling class abandoned the city for Venetian Lagoon, according to a chronicle. The city did not easily recover from this blow, and Padua was still weak when the Franks succeeded the Lombards as masters of northern Italy.

At the Diet of Aix-la-Chapelle (828), the duchy and march of Friuli, in which Padua lay, was divided into four counties, one of which took its title from the city of Padua.

The end of the early Middle Ages at Padua was marked by the sack of the city by the Magyars in 899. It was many years before Padua recovered from this ravage.

During the period of episcopal supremacy over the cities of northern Italy, Padua does not appear to have been either very important or very active. The general tendency of its policy throughout the war of investitures was Imperial and not Roman; and its bishops were, for the most part, Germans.

Under the surface, several important movements were taking place that were to prove formative for the later development of Padua.

At the beginning of the 11th century the citizens established a constitution, composed of a general council or legislative assembly and a credenza or executive body.

During the next century they were engaged in wars with Venice and Vicenza for the right of water - way on the Bacchiglione and the Brenta. This meant that the city grew in power and self reliance.

The great families of Camposampiero, Este and Da Romano began to emerge and to divide the Paduan district among themselves. The citizens, in order to protect their liberties, were obliged to elect a podestà. Their choice first fell on one of the Este family.

A fire devastated Padua in 1174. This required the virtual rebuilding of the city.

The temporary success of the Lombard League helped to strengthen the towns. However their civic jealousy soon reduced them to weakness again. As a result, in 1236 Frederick II found little difficulty in establishing his vicar Ezzelino III da Romano in Padua and the neighboring cities, where he practiced frightful cruelties on the inhabitants. Ezzelino was unseated in June 1256 without civilian bloodshed, thanks to Pope Alexander IV.

Padua then enjoyed a period of calm and prosperity: the basilica of the saint was begun; and the Paduans became masters of Vicenza. The University of Padua (the second in Italy, after Bologna) was founded in 1222, and as it flourished in the 13th century Padua outpaced Bologna, where no effort had been made to expand the revival of classical precedents beyond the field of jurisprudence, to become a center of early humanist researches, with a first hand knowledge of Roman poets that was unrivaled in Italy or beyond the Alps.

However the advances of Padua in the 13th century finally brought the commune into conflict with Can Grande della Scala, lord of Verona. In 1311 Padua had to yield to Verona.

Jacopo da Carrara was elected lord of Padua in 1318. From then till 1405, nine members of the moderately enlightened Carraresi family succeeded one another as lords of the city, with the exception of a brief period of Scaligeri overlordship between 1328 and 1337 and two years (1388 – 1390) when Giangaleazzo Visconti held the town. The Carraresi period was a long period of restlessness, for the Carraresi were constantly at war. Under Carrarese rule the early humanist circles in the university were effectively disbanded: Albertino Mussato, the first modern poet laureate, died in exile at Chiogga in 1329, and the eventual heir of the Paduan tradition was the Tuscan Petrarch.

In 1387 John Hawkwood won the Battle of Castagnaro for Padua, against Giovanni Ordelaffi, for Verona. The Carraresi period finally came to an end as the power of the Visconti and of Venice grew in importance.

Padua passed under Venetian rule in 1405, and so mostly remained until the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797.

There was just a brief period when the city changed hands (in 1509) during the wars of the League of Cambray. On 10 December 1508, representatives of the Papacy, France, the Holy Roman Empire and Ferdinand I of Spain concluded the League of Cambrai against the Republic. The agreement provided for the complete dismemberment of Venice's territory in Italy and for its partition among the signatories: Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I of the Habsburg, was to receive Padua in addition to Verona and other territories. In 1509 Padua was taken for just a few weeks by Imperial supporters. Venetian troops quickly recovered it and successfully defended Padua during siege by Imperial troops. (Siege of Padua (1509)). The city was governed by two Venetian nobles, a podestà for civil and a captain for military affairs. Each was elected for sixteen months. Under these governors, the great and small councils continued to discharge municipal business and to administer the Paduan law, contained in the statutes of 1276 and 1362. The treasury was managed by two chamberlains; and every five years the Paduans sent one of their nobles to reside as nuncio in Venice, and to watch the interests of his native town.

Venice fortified Padua with new walls, built between 1507 and 1544, with a series of monumental gates.

In 1797 the Venetian Republic was wiped off the map by the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Padua was ceded to the Austrian Empire; then in 1806 the city passed to the French puppet Kingdom of Italy. After the fall of Napoleon, in 1814, the city became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Lombardy - Venetia.

The Austrians were unpopular with progressive circles in northern Italy, but the feelings of the population (from the lower to the upper classes) towards the Austrian rule were mixed. In Padua, the year of revolutions of 1848 saw a student revolt which on February 8 turned the University and the Caffè Pedrocchi into battlegrounds in which students and ordinary Paduans fought side by side. The revolt was however short lived, and there were no other uprisings under the Austrian Empire, as in Venice or in other parts of Italy; while opponents to Austria were forced to exile.

Under Austrian rule, Padua began its industrial development; one of the first Italian rail tracks, Padua - Venice, was built in 1845.

In 1866 the battle of Koniggratz gave Italy the opportunity, as an allied of Prussia, to take Venetia, and Padua was also annexed to the recently formed Kingdom of Italy.

Annexed to Italy during 1866, Padua was at the center of the poorest area of Northern Italy, as Veneto was until 1960s. Despite this, the city flourished in the following decades both economically and socially, developing its industry, being an important agricultural market and having a very important cultural and technological center as the University. The city hosted also a major military command and many regiments.

When Italy entered World War I on 24 May 1915, Padua was chosen as the main command of the Italian Army. The king, Vittorio Emanuele III, and the commander in chief Cadorna went to live in Padua for the war period. After the defeat of Italy in the battle of Caporetto in autumn 1917, the front line was situated on the river Piave. This was just 50 – 60 km from Padua, and the city was now in range from the Austrian artillery. However the Italian military command did not withdraw. The city was bombed several times (about 100 civilian deaths). A memorable feat was Gabriele D'Annunzio's flight to Vienna from the nearby San Pelagio Castle air field.

A year later, the danger to Padua was removed. In late October 1918, the Italian Army won the decisive battle of Vittorio Veneto (exactly a year after Caporetto), and the Austrian forces collapsed. The armistice was signed in Padua, at Villa Giusti, on 3 November 1918, with Austria - Hungary surrendering to Italy.

During the war, industry progressed strongly, and this gave Padua a base for further post war development. In the years immediately following the Great War, Padua developed outside the historical town, enlarging and growing in population. even if labor and social strife was rampant at the time.

As in many other areas in Italy and abroad, Padua experienced great social turmoil in the years immediately following the Great War. The city was swept by strikes and clashes, factories and fields were subject to occupation, and war veterans struggled to re-enter civilian life. Many supported a new political way: Fascism. As in other parts of Italy, the fascist party in Padua soon came to be seen as the defender of property and order against revolution. The city was also the site of one of the largest fascist mass rallies, with some 300,000 people reportedly attending one Mussolini speech.

New buildings, in typical fascist architecture, sprang up in the city. Examples can be found today in the buildings surrounding Piazza Spalato (today Piazza Insurrezione), the railway station, the new part of City Hall, and part of the Bo Palace hosting the University.

Following Italy's defeat in the Second World War on 8 September 1943, Padua became part of the Italian Social Republic, i.e., the puppet state of the Nazi occupiers. The city hosted the Ministry of Public Instruction of the new state, as well as military and militia commands and a military airport. The Resistenza, the Italian partisans, was very active against both the new fascist rule and the Nazis. One of the main leaders was the University vice - chancellor Concetto Marchesi.

Padua was bombed several times by Allied planes. The worst hit areas were the railway station and the northern district of Arcella. During one of these bombings, the beautiful Eremitani church, with Mantegna frescoes, was destroyed (considered by some art historians to be Italy's biggest wartime cultural loss).

The city was finally liberated by partisans and New Zealand troops on 28 April 1945. A small Commonwealth War Cemetery is in the west part of the city, to remember the sacrifice of these troops.

After the war, the city developed rapidly, reflecting Veneto's rise from being the poorest region in northern Italy to one of the richest and most active regions of modern Italy.

- The Scrovegni Chapel (Italian: Cappella degli Scrovegni) is Padua's most famous sight. It houses a remarkable cycle of frescoes completed in 1305 by Giotto. It was commissioned by Enrico degli Scrovegni, a wealthy banker, as a private chapel once attached to his family's palazzo. It is also called the "Arena Chapel" because it stands on the site of a Roman era arena. The fresco cycle details the life of the Virgin Mary and has been acknowledged by many to be one of the most important fresco cycles in the world. Entrance to the chapel is an elaborate ordeal, as it involves spending 15 minutes prior to entrance in a climate controlled, airlocked vault, used to stabilize the temperature between the outside world and the inside of the chapel. This is to improve preservation.

- The Palazzo della Ragione, with its great hall on the upper floor, is reputed to have the largest roof unsupported by columns in Europe; the hall is nearly rectangular, its length 81.5 m (267.39 ft), its breadth 27 m (88.58 ft), and its height 24 m (78.74 ft); the walls are covered with allegorical frescoes; the building stands upon arches, and the upper story is surrounded by an open loggia, not unlike that which surrounds the basilica of Vicenza. The Palazzo was begun in 1172 and finished in 1219. In 1306, Fra Giovanni, an Augustinian friar, covered the whole with one roof. Originally there were three roofs, spanning the three chambers into which the hall was at first divided; the internal partition walls remained till the fire of 1420, when the Venetian architects who undertook the restoration removed them, throwing all three spaces into one and forming the present great hall, the Salone. The new space was refrescoed by Nicolo' Miretto and Stefano da Ferrara, working from 1425 to 1440. Beneath the great hall, there is a centuries old market.

- In the Piazza dei Signori is the beautiful loggia called the Gran Guardia, (1493 – 1526), and close by is the Palazzo del Capitaniato, the residence of the Venetian governors, with its great door, the work of Giovanni Maria Falconetto, the Veronese architect - sculptor who introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua and who completed the door in 1532. Falconetto was the architect of Alvise Cornaro's garden loggia, (Loggia Cornaro), the first fully Renaissance building in Padua. Nearby, the Cathedral, remodeled in 1552 after a design of Michelangelo. It contains works by Nicolò Semitecolo, Francesco Bassano and Giorgio Schiavone. The nearby Baptistry, consecrated in 1281, houses the most important frescoes cycle by Giusto de' Menabuoi.

- The most famous of the Paduan churches is the Basilica di Sant'Antonio da Padova, locally simply known as "Il Santo". The bones of the saint rest in a chapel richly ornamented with carved marbles, the work of various artists, among them Sansovino and Falconetto. The basilica was begun about the year 1230 and completed in the following century. Tradition says that the building was designed by Nicola Pisano. It is covered by seven cupolas, two of them pyramidal. There are also four beautiful cloisters to visit.

- Donatello's magnificent equestrian statue of the Venetian general Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni) can be found on the piazza in front of the Basilica di Sant'Antonio da Padova. It was cast in 1453, and was the first full size equestrian bronze cast since antiquity. It was inspired by the Marcus Aurelius equestrian sculpture at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

- Not far from the Gattamelata statue are the St. George Oratory (13th century), with frescoes by Altichiero, and the Scuola di S. Antonio (16th century), with frescoes by Tiziano (Titian).

- One of the best known symbols of Padua is the Prato della Valle, a 90,000 m2 (968,751.94 sq ft) elliptical square. This is believed to be the biggest in Europe, after Place des Quinconces in Bordeaux. In the center is a wide garden surrounded by a ditch, which is lined by 78 statues portraying famous citizens. It was created by Andrea Memmo in the late 18th century. Memmo once resided in the monumental 15th century Palazzo Angeli, which now houses the Museum of Precinema.

- Abbey of Santa Giustina and adjacent Basilica. In the 15th century, it became one of the most important monasteries in the area, until it was suppressed by Napoleon in 1810. In 1919 it was reopened. The tombs of several saints are housed in the interior, including those of Justine, St. Prosdocimus, St. Maximus, St. Urius, St. Felicita, St. Julianus, as well as relics of the Apostle St. Matthias and the Evangelist St. Luke. This is home to some art, including the Martyrdom of St. Justine by Paolo Veronese. The complex was founded in the 5th century on the tomb of the namesake saint, Justine of Padua.

- The Church of the Eremitani is an Augustinian church of the 13th century, containing the tombs of Jacopo (1324) and Ubertinello (1345) da Carrara, lords of Padua, and for the chapel of SS James and Christopher, formerly illustrated by Mantegna's frescoes. This was largely destroyed by the Allies in World War II, because it was next to the Nazi headquarters. The old monastery of the church now houses the municipal art gallery.

- Santa Sofia is probably Padova's most ancient church. The crypt was begun in the late 10th century by Venetian craftsmen. It has a basilica plan with Romanesque - Gothic interior and Byzantine elements. The apse was built in the 12th century. The edifice appears to be tilting slightly due to the soft terrain.

- The church of San Gaetano (1574 – 1586) was designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, on an unusual octagonal plan. The interior, decorated with polychrome marbles, houses a precious Madonna and Child by Andrea Briosco, in Nanto stone.

- The 16th century, baroque Padua Synagogue.

- At the center of the historical city, the buildings of Palazzo del Bò, the center of the University

- The City Hall, called Palazzo Moroni, the wall of which is covered by the names of the Paduan dead in the different wars of Italy and which is attached to Palazzo della Ragione;

- The Caffé Pedrocchi, built in 1831 by architect Giuseppe Jappelli in neoclassical style with Egyptian influence. This is a little jewel of history and art for a café open for almost two centuries. It hosts the Risorgimento museum, and the near building of the Pedrocchino ("little Pedrocchi") in neogothic style.

- The city center is surrounded by the 11 km long city walls, built during the early 16th century, by architects that included Michele Sanmicheli. There are only a few ruins left, together with two gates, of the smaller and inner 13th century walls. There is also a castle, the Castello. Its main tower was transformed between 1767 and 1777 into an astronomical observatory known as Specola. However the other buildings were used as prisons during the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now being restored.

- The Ponte San Lorenzo, a Roman bridge largely underground, along with the ancient Ponte Molino, Ponte Altinate, Ponte Corvo and Ponte S. Matteo

In the neighbourhood of Padua are numerous noble villas. These include:

- Villa Molin, in the Mandria fraction, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1597.

- Villa Mandiriola, (17th century), at Albignasego

- Villa Pacchierotti-Trieste (17th century), at Limena

- Villa Cittadella-Vigodarzere (19th century), at Saonara

- Villa Selvatico da Porto (15th-18th century), at Vigonza

- Villa Loredan, at Sant'Urbano.

- Villa Contarini, at Piazzola sul Brenta, built in 1546 by Palladio and enlarged in the following centuries, is the most important.

Padua has long been famous for its university, founded in 1222. Under the rule of Venice the university was governed by a board of three patricians, called the Riformatori dello Studio di Padova. The list of professors and alumni is long and illustrious, containing, among others, the names of Bembo, Sperone Speroni, the anatomist Vesalius, Copernicus, Fallopius, Fabrizio d'Acquapendente, Galileo Galilei, William Harvey, Pietro Pomponazzi, Reginald, later Cardinal Pole, Scaliger, Tasso and Sobieski. It is also where, in 1678, Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia became the first woman in the world to graduate. The university hosts the oldest anatomy theater, built in 1594.

The university also hosts the oldest botanical garden (1545) in the world. The botanical garden Orto Botanico di Padova was founded as the garden of curative herbs attached to the University's faculty of medicine. It still contains an important collection of rare plants.

The place of Padua in the history of art is nearly as important as its place in the history of learning. The presence of the university attracted many distinguished artists, such as Giotto, Fra Filippo Lippi and Donatello; and for native art there was the school of Francesco Squarcione, whence issued the great Mantegna.

Padua is also the birthplace of the famous architect Andrea Palladio, whose 16th century "ville" (country houses) in the area of Padua, Venice, Vicenza and Treviso are among the most beautiful of Italy and they were often copied during the 18th and 19th centuries; and of Giovanni Battista Belzoni, adventurist, engineer and egyptologist.

The famous sculptor Antonio Canova produced his first work in Padua, one of which is among the statues of Prato della Valle (presently a copy is displayed in the open air, while the original is in the Musei Civici, Civic Museums).

One the most relevant places in the life of the city has

certainly been The Antonianum. Settled among Prato della

Valle, the Saint Anthony church and the Botanic Garden it was built

in 1897 by the Jesuit fathers and kept alive until 2002.

During World War II, under the leadership of P. Messori

Roncaglia SJ, it became the center of the resistance

movement against the Nazis.

Indeed, it briefly survived P. Messori's death and was

sold by the Jesuits in 2004. Some sites are trying to

collect what can still be found of the college: (1) a non-profit pixel site is

collecting links to whatever is available on the web; (2)

a student association created in

the college is still operating and connecting Alumni.