<Back to Index>

- City of Modena, 3rd Century B.C.

- City of Reggio Emilia, 187 B.C.

- City of Treviso, 300 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

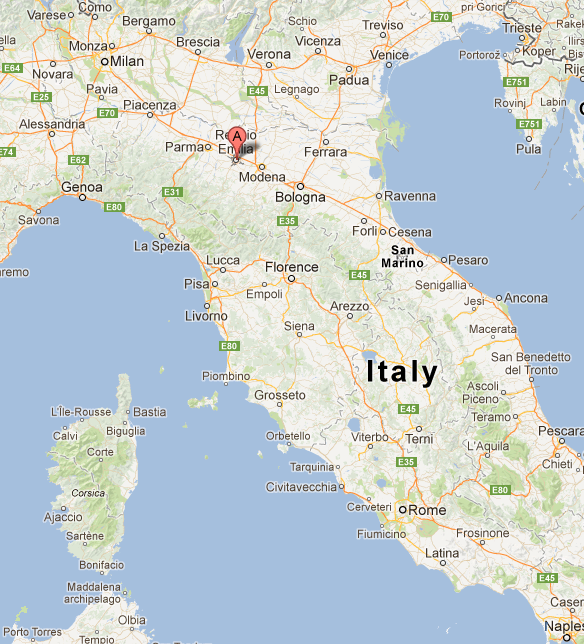

Modena (Etruscan: Mutna; Latin: Mutina; Modenese: Mòdna) is a city and comune (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia - Romagna region of Italy.

An ancient town, it is the seat of an archbishop, but is now best known as "the capital of engines", since the factories of the famous Italian sports car makers Ferrari, De Tomaso, Lamborghini, Pagani and Maserati are, or were, located here and all, except Lamborghini, have headquarters in the city or nearby. Lamborghini is headquartered not far away in Sant' Agata Bolognese, in the adjacent Province of Bologna. One of Ferrari's cars, the 360 Modena, was named after the town itself. Also, one of the colors for Ferraris is Modena yellow.

The University of Modena, founded in 1175 and expanded by Francesco II d'Este in 1686, has traditional strengths in economics, medicine and law and is the second oldest athenaeum in Italy, sixth in the whole world. Italian officers are trained at the Italian Military Academy, located in Modena, and partly housed in the Baroque Ducal Palace. The Biblioteca Estense houses historical volumes and 3,000 manuscripts.

Modena is well known in culinary circles for its production of balsamic vinegar and also for its Military Academy, Italy's "Westpoint", which is housed in the Ducal Palace.

Famous Modenesi include Mary of Modena, the Queen consort of England and Scotland; operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti (1935 – 2007) and soprano Mirella Freni, born in Modena itself; Enzo Ferrari (1898 – 1988), eponymous founder of the Ferrari motor company; the Catholic Priest and Senior Exorcist of Vatican Gabriele Amorth; and the rock singer Vasco Rossi who was born in Zocca, one of the 47 comuni in the Province of Modena.

Modena lies on the Pianura Padana, and is bounded by the two rivers Secchia and Panaro, both affluents of the Po River. Their presence is symbolized by the Two Rivers Fountain in the city's center, by Giuseppe Graziosi. The city is connected to the Panaro by the Naviglio channel.

The Apennines ranges begin some 10 km from the city, to the south.

The commune is divided into four circoscrizioni. These are:

- Centro storico (Historical Center, San Cataldo)

- Crocetta (San Lazzaro - East Modena, Crocetta)

- Buon Pastore (Buon Pastore, Sant' Agnese, San Damaso)

- San Faustino (S.Faustino - Saliceta San Giuliano, Madonnina - Quattro Ville)

The legislative body of the municipality (commune) is the City

Council (Consiglio Comunale), which is composed by

35 members elected every five years. Modena's executive

body is the City Committee (Giunta Comunale),

composed by 9 assessors, the deputy - mayor and the mayor.

The territory around Modena (Latin: Mutina, Etruscan: Mutna) was inhabited by the Villanovans in the Iron Age, and later by Ligurian tribes, Etruscans, and the Gaulish Boii (the settlement itself being Etruscan). Although the exact date of its foundation is unknown, it is known that it was already in existence in the 3rd century BC, for in 218 BC, during Hannibal's invasion of Italy, the Boii revolted and laid siege to the city. Livy described it as a fortified citadel where Roman magistrates took shelter. The outcome of the siege is not known, but the city was most likely abandoned after Hannibal's arrival. Mutina was refounded as a Roman colony in 183 BC, to be used as a military base by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, causing the Ligurians to sack it in 177 BC. Nonetheless, it was rebuilt, and quickly became the most important center in Cisalpine Gaul, both because of its strategic importance and because it was on an important crossroads between Via Aemilia and the road going to Verona.

In the 1st century BC Mutina was besieged twice. The first siege was by Pompey in 78 BC, when Mutina was defended by Marcus Junius Brutus (a populist leader, not to be confused with his son, Caesar's best known assassin). The city eventually surrendered out of hunger, and Brutus fled, only to be slain in Regium Lepidi. In the civil war following Caesar's assassination, the city was besieged once again, this time by Mark Antony, in 44 BC, and defended by Decimus Junius Brutus. Octavian relieved the city with the help of the Senate.

Cicero called it Mutina splendidissima ("most beautiful Mutina") in his Philippics (44 BC). Until the 3rd century AD, it kept its position as the most important city in the newly formed Aemilia province, but the fall of the Empire brought Mutina down with it, as it was used as a military base both against the barbarians and in the civil wars. It is said that Mutina was never sacked by Attila, for a dense fog hid it (a miracle said to be provided by Saint Geminianus, bishop and patron of Modena), but it was eventually buried by a great flood in the 7th century and abandoned.

As of December, 2008, Italian researchers have discovered the pottery center where the oil lamps that lit the ancient Roman empire were made. Evidence of the pottery workshops emerged in Modena, in central - northern Italy, during construction work to build a residential complex near the ancient walls of the city. "We found a large ancient Roman dumping filled with pottery scraps. There were vases, bottles, bricks, but most of all, hundreds of oil lamps, each bearing their maker's name", Donato Labate, the archaeologist in charge of the dig, stated.

Its exiles founded a new city a few miles to the northwest, still represented by the village of Cittanova (literally "new city"). About the end of the 9th century, Modena was restored and refortified by its bishop, Ludovicus. At about this time the Song of the Watchmen of Modena was composed. Later the city was part of the possessions of the Countess Matilda of Tuscany, becoming a free commune starting from the 12th century. In the wars between Emperor Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX Modena sided with the emperor.

The Este family were identified as lords of Modena from 1288 (Obizzo d'Este). After the death of Obizzo's successor (Azzo VIII, in 1308) the commune reasserted itself, but by 1336 the Este family was permanently in power. Under Borso d'Este Modena was made a duchy.

Enlarged and fortified by Ercole II, it was made the primary ducal residence when Ferrara, the main Este seat, fell to the Pope in 1598. Francesco I d'Este, Duke of Modena (1629 – 1658) built the citadel and began the palace, which was largely embellished by Francesco II. In the 18th century, Rinaldo d'Este was twice driven from his city by French invasions, and Francesco III built many of Modena's public buildings, but the Este paintings were sold and many of them wound up in Dresden. Ercole III died in exile at Treviso, having refused Napoleonic offers of compensation when Modena was made part of the Napoleonic Cispadane Republic. His only daughter, Maria Beatrice d'Este, married Ferdinand I, Archduke of Austria - Este, son of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria; and in 1814 their eldest son, Francis IV, received back the estates of the Este. Quickly, in 1816, he dismantled the fortifications that might well have been used against him and began Modena's years under Austrian rule which, despite being just, constitutional and fair, nevertheless had to face another foreign inspired rebellion in 1830, this time happily unsuccessful.

His son Francis V was also a just ruler and famously tended the victims of war and cholera with his own hands. However, he too had to face yet more foreign inspired revolutions and was temporarily expelled from Modena in the European Revolutions of 1848. He was restored, amidst wide popular acclaim, by Austrian troops. Ten years later, on August 20, 1859, the revolutionaries again invaded (this time the Piedmontese), annexing Modena into the revolutionary Savoyard nation of Italy as a territorial part of the Kingdom of Italy.

The Cathedral of Modena and the annexed campanile are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Begun under the direction of the Countess Matilda of Tuscany with its first stone laid June 6, 1099 and its crypt ready for the city's patron, Saint Geminianus, and consecrated only six years later, the Duomo of Modena was finished in 1184. The building of a great cathedral in this flood prone ravaged former center of Arianism was an act of urban renewal in itself, and an expression of the flood of piety that motivated the contemporary First Crusade. Unusually, the master builder's name, Lanfranco, was celebrated in his own day: the city's chronicler expressed the popular confidence in the master - mason from Como, Lanfranco: by God's mercy the man was found (inventus est vir). The sculptor Wiligelmus who directed the mason's yard was praised in the plaque that commemorated the founding. The program of the sculpture is not lost in a welter of detail: the wild dangerous universe of the exterior is mediated by the Biblical figures of the portals leading to the Christian world of the interior. In Wiligelmus' sculpture at Modena, the human body takes on a renewed physicality it had lost in the schematic symbolic figures of previous centuries. At the east end, three apses reflect the division of the body of the cathedral into nave and wide aisles with their bold, solid masses. Modena's Duomo inspired campaigns of cathedral and abbey building in emulation through the valley of the Po.

The Gothic campanile (1224 – 1319) is called Torre della Ghirlandina from the bronze garland surrounding the weathercock.

The Ducal Palace, begun by Francesco I d'Este in 1634 and finished by Francis V, was the seat of the Este court from the 17 - 19th century. The palace occupies the site of the former Este Castle, once located in the periphery of the city. Although generally credited to Bartolomeo Avanzini, it has been suggested that advice and guidance in the design process had been sought from the contemporary luminaries, Cortona, Bernini and Borromini.

The Palace currently houses the Accademia Militare di Modena, the Military Museum and a precious Library.

The Palace has a Baroque façade from which the Honor Court, where the military ceremonies are held, and the Honor Staircase can be accessed. The Central Hall has a frescoed ceiling with the 17th century Incoronation of Bradamante by Marco Antonio Franceschini. The Salottino d'Oro ("Golden Hall"), covered with gilted removable panels, was used by Duke Francis III as his main cabinet of work.

Facing the Piazza Grande (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), the Town Hall of Modena was put together in the 17th - 18th centuries from several preexisting edifices built from 1046 as municipal offices.

It is characterized by a Clock Tower (Torre dell' Orologio, late 15th century), once paired with another tower (Torre Civica) demolished after an earthquake in 1671. In the interior, noteworthy is the Sala del Fuoco ("Fire Hall"), with a painted frieze by Niccolò dell' Abbate (1546) portraying famous characters from Ancient Rome against a typical Emilia background. The Camerino dei Confirmati ("Chamber of the Confirmed") houses one of the symbols of the city, the Secchia Rapita, a bucket kept in memory of the victorious Battle of Zappolino (1325) against Bologna. This relic inspired the poem of the same title by Alessandro Tassoni. Another relic from the Middle Ages in Modena is the Preda Ringadora, a rectangular marble stone next to the palace porch, used as a speakers' platform, and the statue called La Bonissima ("The Very Good"): the latter, portraying a female figure, was erected in the square in 1268 and later installed over the porch.

The Palace Museum, on the St. Augustine square, is an example of civil architecture from the Este period, built as a Hostel for the Poor together with the nearby Hospital in the late 18th century. Today it houses the main museums of Modena:

- Estense Gallery, with works by Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Guido Reni, Correggio, Cosmé Tura and brothers Annibale and Agostino Carracci. The most famous works are the two portraits of Francis I d'Este, a sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and a canvas by Diego Velázquez.

- Estense Library, one of the most important libraries in Italy.

- Museum of Medieval and Modern Art.

- Municipal Museum of Risorgimento.

- Este Headstones Museum.

- Graziosi Chalks Gallery.

- Archaeological and Ethnological Museum.

- San Vincenzo was erected in the 17th century over a church known from the 13th century. The works were begun by Paolo Reggiano, who was followed by Bernardo Castagnini, probably helped by the young Guarino Guarini. The interior contains frescoes by Sigismondo Caula portraying episodes of the life of Saint Vincent and Saint Cajetan. The dome was destroyed during World War II. This church houses the funerary monuments of the Este Dukes.

- Santa Maria della Pomposa (also known as Aedes Muratoriana) is probably the most ancient religious edifice, being mentioned as early as 1135. Little remains of the original Middle Ages temple can be seen. The church is mainly linked to Ludovico Antonio Muratori, who was its parish priest from 1716 to 1750 and rebuilt it almost from scratch.

- The church of San Giovanni Decollato ("St. John Baptist Beheaded") was built in the 16th century over a preexisting temple dedicated to St. Michael, and modified in the 18th century.

- The church of St. Augustine was built in the 14th century, but largely renovated for the funerals of Alfonso IV d'Este in 1663. The sober original structure has now 17th stuccoes and a paneled ceiling. The most notable artwork is the Deposition (1476) by the Modenese Antonio Begarelli, once in the church of St. John the Baptist. Traces of a 14th century fresco by Tommaso da Modena can still be seen.

- The church of St. Francis was built by the Franciscans from 1244, and finished after more than two centuries. A sober Gothic-style edifice, it houses one of Begarelli's masterworks, a Deposition of Christ made up of thirteen statues.

- The church of St. Peter was erected, according to tradition, over the temple of Jupiter Capitulinus. The current edifice is from 1476, built next to a Benedictine abbey founded in 996 oustide the city walls, and is one of the few Renaissance architecture in Modena. The interior has a precious 15th century organ and numerous terracotta works by Begarelli. The campanile is from 1629.

- The church of St. George is also known as the Sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin Helper of the Modenese People, who boasts a venerated image over the high altar. The latter is a work in polychrome marbles by Antonio Loraghi (1666). The church has a Greek plan and was constructed from 1647.

The Teatro Comunale Modena (Community Theater of Modena, but renamed in October 2007 as Teatro Comunale Luciano Pavarotti) is an opera house in the town of Modena, (Emilia - Romagna province), Italy. The idea for the creation of the present theater dates from 1838, when it became apparent that the then existing Teatro Comunale di via Emilia (in dual private and public ownership) was no longer suitable for staging opera. However, this house had been the venue for presentations of all of the works of Donizetti, Bellini and Rossini up to this time, and a flourishing operatic culture existed in Modena.

Under the Mayor of Modena in collaboration with the Conservatorio dell' Illustrissima Comunita (Conservatory of the Most Illustrious Community), architect Francesco Vandelli was engaged to design the Teatro dell' Illustrissima Comunita, as the theater was first called, "for the dignity of the city and for the transmission of the scenic arts". Paid for in the manner typical of the time - from the sale of boxes - in addition to a significant gift from Duke Friedrich IV, Vandelli created a design for the new theater combining ideas from those in Piacenza, Mantua and Milan, and it opened on 2 October 1841 with a performance of Gandini's Adelaide di Borgogna al Castello di Canossa, an opera specially commissioned for the occasion.

Reggio Emilia (Emilian: Rèz, Latin: Regium Lepidi) is an affluent city in northern Italy, in the Emilia - Romagna region. It has about 170,000 inhabitants and is the main comune (municipality) of the Province of Reggio Emilia.

The town is also referred to by its more official name of Reggio nell' Emilia. The inhabitants of Reggio nell' Emilia (called Reggiani) usually call their town by the simple name of Reggio. In some ancient maps the town is also named Reggio di Lombardia.

The old town has an hexagonal form, which derives from the ancient walls, and the main buildings are from the 16th - 17th centuries. The commune's territory is totally on a plain, crossed by the Crostolo stream.

Though not Roman in origin, Reggio began as an historical site with the construction by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus of the Via Aemilia, leading from Piacenza to Rimini (187 BC). Reggio became a judicial administration center, with a forum called at first Regium Lepidi, then simply Regium, whence the city's current name.

During the Roman age Regium is cited only by Festus and Cicero, as one of the military stations on the Via Aemilia. However, it was a flourishing city, a Municipium with its own statutes, magistrates and art collegia.

Apollinaris of Ravenna brought Christianity in the 1st century CE. The sources confirm the presence of a bishopric in Reggio after the Edict of Milan (313). In 440 the Reggio's diocese was submitted to Ravenna by Western Roman Emperor Valentinianus III. At the end of the 4th century, however, Reggio had decayed so much that Saint Ambrose included it among the dilapidated cities. Further damage occurred with the Barbarian invasions. At the fall of the Western Empire (476), Reggio was part of Odoacer's reign. In 489 it was in the Ostrogothic kingdom; later (539) it belonged to the Exarchate of Ravenna, but was conquered by Alboin's Lombards in 569. Reggio was chosen as the Duchy of Reggio seat.

In 773 the Franks subjected Reggio, and Charlemagne gave the bishop royal authority over the city and established the diocese's limits (781). In 888 Reggio was handed over to the Kings of Italy. In 899 the Magyars heavily damaged it, killing Bishop Azzo II. As a result of this, new walls were built. On October 31, 900, Emperor Louis III gave authority for the erection of a castrum (castle) in the city's center.

In 1002 Reggio's territory, together with that of Parma, Brescia, Modena, Mantova and Ferrara, were merged into the mark of Tuscany, later held by Matilde of Canossa.

Reggio became a free commune around the end of the 11th or the beginning of the 12th century. In 1167 it was a member of the Lombard League and took part in the Battle of Legnano. In 1183 the city signed the Treaty of Konstanz, from which the city's consul, Rolando della Carità, received the imperial investiture. The subsequent peace spurred a period of prosperity: Reggio adopted new statutes, had a mint, schools with celebrated masters, and developed its trades and arts. It also increasingly subjugated the castles of the neighboring areas. At this time the Crostolo stream was deviated westwards, to gain space for the city. The former course of the stream was turned into an avenue called Corso della Ghiara (gravel), nowadays Corso Garibaldi.

The 12th and 13th century, however, were also a period of violent internal struggle, with parties of Scopazzati (meanining - swept away from the city with brooms - these were the nobles, not very martial, apparently) and Mazzaperlini (meaning - lice killers - the plebeians) and later those of Ruggeri and Malaguzzi, involved in bitter domestic rivalry. In 1152 Reggio also warred with Parma and in 1225 with Modena, as part of the general struggle between the Guelphs and Ghibellines. In 1260 25,000 penitents, led by a Perugine hermit, entered the city, and this event calmed the situation for a while, spurring a momentous flourishing of religious fervor. But disputes soon resurfaced, and as early as 1265 the Ghibellines killed the Guelph's leader, Caco da Reggio, and gained preeminence. Arguments with the Bishop continued and two new parties formed, the Inferiori and Superiori. Final victory went to the latter.

To thwart the abuses of powerful families such as the Sessi, Fogliani and Canossa, the Senate of Reggio gave the city's rule for a period of three years to the Este member Obizzo II d'Este. This choice marked the future path of Reggio under the seignory of that family, as Obizzo continued to rule de facto after his mandate has ceased. His son Azzo was expelled by the Reggiani in 1306, creating a republic ruled by 800 common people. In 1310 the Emperor Henry VII imposed Marquis Spinetto Malaspina as vicar, but he was soon driven out. The republic ended in 1326 when Cardinal Bertrando del Poggetto annexed Reggio to the Papal States.

The city was subsequently under the suzerainty of John of Bohemia, Nicolò Fogliani and Martino della Scala, who in 1336 gave it to Luigi Gonzaga. Gonzaga built a citadel in the St. Nazario quarter, and destroyed 144 houses. In 1356 the Milanese Visconti, helped by 2,000 exiled Reggiani, captured the city, starting an unsettled period of powersharing with the Gonzaga. In the end the latter sold Reggio to the Visconti for 5,000 ducats. In 1405 Ottobono Terzi of Parma seized Reggio, but was killed by Michele Attendolo, who handed the city over to Nicolò III d'Este, who therefore became seignor of Reggio. The city however maintained a relevant autonomy, with laws and coinage of its own. Niccolò was succeeded by his illegitimate son Lionello, and, from 1450, by Borso d'Este.

In 1452 Borso was awarded the title of Duke of Reggio and Modena by Frederick III. Borso's successor, Ercole I, imposed heavy levies on the city and named the poet Matteo Maria Boiardo, born in the nearby town of Scandiano, as its governor. Later another famous Italian writer, Francesco Guicciardini, held the same position. In 1474, the great poet Ludovico Ariosto, author of Orlando Furioso, was born in the Malaguzzi palace, near the present day townhall. He was the first son of a knight from Ferrara, who was in charge of the Citadel, and a noblewoman from Reggio, Daria Maleguzzi Valeri. As an adult man he would be sent to Reggio as governor on behalf of the dukes of Ferrara, and would spend time in a villa just outside the town ("Il Mauriziano") that still stands.

In 1513 Reggio was handed over to Pope Julius II. The city was returned to the Este after the death of Hadrian VI on September 29, 1523. In 1551 Ercole II d'Este destroyed the suburbs of the city in his program of reconstruction of the walls. At the end of the century work on the city's famous Basilica della Ghiara began, on the site where a miracle was believed to have occurred. The Este rule continued until 1796, with short interruptions in 1702 and 1733 - 1734.

The arrival of the republican French troops was greeted with enthusiasm in the city. On August 21, 1796, the ducal garrison of 600 men was driven off, and the Senate claimed the rule of Reggio and its duchy. On September 26, the Provisional Government's volunteers pushed back an Austrian column, in the Battle of Montechiarugolo. Though minor, this clash is considered the first one of the Italian Risorgimento. Napoleon himself awarded the Reggiani with 500 rifles and 4 guns. Later he occupied Emilia and formed a new province, the Cispadane Republic, whose existence was proclaimed in Reggio on January 7, 1797. The Italian national flag, named Il Tricolore (three - color flag), was sewn on that occasion by Reggio women. In this period of patriotic fervor, Jozef Wybicki, a lieutenant in the Polish troops of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, an ally of Napoleon, composed the Mazurek Dąbrowskiego in Reggio, which in 1927 became the Polish national anthem.

The 1815 Treaty of Vienna returned Reggio to Francis IV d'Este, but in 1831 Modena rose up against him, and Reggio followed its example organizing a corps under the command of General Carlo Zucchi. However, on March 9, the Duke conquered the city with his escort of Austrian soldiers.

In 1848 Duke Francis V left his state fearing a revolution and Reggio proclaimed its union with Piemonte. The latter's defeat at Novara brought the city back under the Estense control. In 1859 Reggio, under dictator Luigi Carlo Farini, became part of the united Italy and, with the plebiscite of March 10, 1860, definitively entered the new unified Kingdom.

Reggio then went through a period of economic and population growth from 1873 to the destruction of the ancient walls. In 1911 it had 70,000 inhabitants. A strong socialist tradition grew. On July 7, the city hosted the 13th National Congress of the Italian Socialist Party. On July 26, 1943, the fascist régime's fall was cheered with enthusiasm by the Reggiani. Numerous partisan bands were formed in the city and surrounding countryside.

Jews began arriving Reggio in the early 15th century. Many Jews were Sephardim from Spain, Portugal and other parts of Italy. Nearly all were fleeing religious persecution. The Jewish community was prosperous and enjoyed considerable growth for the next several hundred years. After the Napoleonic era the Jews of Reggio gained emacipation and began to migrate to other parts of Europe looking for greater economic and social freedom. Thus, the Jewish community in Reggio began to decline. The German occupation during World War II and the Holocaust hastened the decline. Today, only a handful of Jewish families remain in Reggio. However, a functioning synagogue and burial ground still exist.

Treviso (Venetian: Trevixo) is a city and comune in Veneto, northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Treviso and the municipality has 82,854 inhabitants (as of November 2010): some 3,000 live within the Venetian walls (le Mura) or in the historical and monumental center, some 80,000 live in the urban center proper while the city hinterland has a population of approximately 170,000. The city is home to the headquarters of clothing retailer Benetton, appliance maker De'Longhi, and bicycle maker Pinarello.

For some scholars, the ancient city of Tarvisium derived its name from a settlement of the Celtic tribe of the Taurusci. Others have attributed the name instead to the Greek root tarvos, meaning "bull".

Tarvisium, then a city of the Veneti, became a municipium in 89 BC after the Romans added Cisalpine Gaul to their dominions. Citizens were ascribed to the Roman tribe of Claudia. The city lay in proximity of the Via Postumia, which connected Opitergium to Aquileia, two major cities of Roman Venetia during Ancient and Early Medieval times. Treviso is rarely mentioned by ancient writers, although Pliny writes of the Silis, that is the Sile River, as flowing ex montibus Tarvisanis.

During the Roman Period, Christianity spread to Treviso. Tradition records that St. Prosdocimus, a Greek who had been ordained bishop by St. Peter, brought the Catholic Faith to Treviso and surrounding areas. By the fourth century, the Christian population grew sufficient to merit a resident bishop. The first documented was named John the Pius who began his epsicopacy in 396 AD.

Treviso went through a demographic and economic decline similar to the rest of Italy after the fall of the Western Empire; however, it was spared by Attila the Hun, and thus, remained an important center during the 6th century. According to tradition, Treviso was the birthplace of Totila, the leader of Ostrogoths during the Gothic Wars. Immediately after the Gothic Wars, Treviso fell under the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna until 568 AD when it was taken by the Lombards, who made it as one of 36 ducal seats and established an important mint. The latter was especially important during the reign of the last Lombard king, Desiderius, and continued to issue coins when northern Italy was annexed to the Frankish Empire. People from the city also played a role in the founding of Venice.

Charlemagne made it the capital of a border March, i.e., the Marca Trevigiana, which lasted for several centuries.

Treviso joined the Lombard League, and gained independence after the Peace of Constance (1183). This lasted until the times when seignories started to be imposed in northern Italy: among the various families who ruled over Treviso, the Da Romano reigned from 1237 to 1260. Struggles between Guelph and Ghibelline factions followed, with the first triumphant in 1283 with Gherardo III da Camino, date after which Treviso lived a significant economical reprise which lasted until 1312. Treviso and her satellite cities, including Castelfranco Veneto, founded by the Trevigiani, in contrapposition to Padua, had become desirable for the neighboring powers, including the da Carrara and Scaligeri. After the fall of the last Caminesi lord, Rizzardo IV, the Marca was the site of continuous struggles and ravages (1329 – 1388).

Treviso's notary and physician, Oliviero Forzetta, was an avid collector of antiquities and drawings; the collection was published in a catalog in 1369, the earliest such catalog to exist to this day.

After a Scaliger domination in 1329 – 1339, the city gave itself to the Republic of Venice, becoming the first notable mainland possession of the Serenissima. From 1318 it was also, for a short time, the seat of a university. Venetian rule brought innumerable benefits, however, Treviso necessarily became involved in the wars of Venice. From 1381 – 1384, the city was captured and ruled by the duke of Austria, and then by the Carraresi until 1388. Having returned to Venice, the city was fortified and given a massive line of (still existent) walls and ramparts: these were renewed in the following century under the direction of Fra Giocondo, two of the gates being built by the Lombardi. The many waterways were exploited with several waterwheels which mainly powered mills for milling grain produced locally. The waterways were all navigable and "barconi" would arrive from Venice at the Port of Treviso (Porto de Fiera) pay duty and offload their merchandise and passengers along Riviera Santa Margherita. Fishermen were able to bring fresh catch every day to the Treviso fish market, which is held still today on an island connected to the rest of the city by two small bridges at either end.

Treviso was taken in 1797 by the French under Mortier, who was made duke of Treviso. French domination lasted until the defeat of Napoleon, after which it passed to the Austro - Hungarian Empire. The citizens, still at heart loyal to the fallen Venetian Republic, were displeased with imperial rule and in March 1848, drove out the Austrian garrison. However, after the town was bombarded, the people were compelled to capitulate in the following June. Austrian rule continued until Treviso was annexed with the rest of Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866.

During World War I, Treviso held a strategic position close to the Austrian front. Just north, the Battle of Vittorio Veneto helped turn the tide of the War.

In Monigo near Treviso during World War II, one of several Italian concentration camps was established for Slovene and Croatian civilians from the Province of Ljubljana. The camp was disbanded with the Italian capitulation in 1943.

At the end of the war, the city suffered an Allied bombing on 7 April 1944 (Good Friday). A large part of the medieval parts of the city center including part of the Palazzo dei Trecento (then rebuilt) were destroyed, causing the deaths of about 1,000 people.

- The Late Romanesque - Early Gothic church of San Francesco, built by the Franciscan community in 1231 – 1270. Used by Napoleonic troops as a stable, it was reopened in 1928. The interior has a single nave with five chapels. On the left wall is a Romanesque - Byzantine fresco portraying St. Christopher (later 13th century). The Grand Chapel has a painting of the Four Evangelists by a pupil of Tommaso da Modena, to whom is instead directly attributed a fresco of Madonna with Child and Seven Saints (1350) in the first chapel on the left. The next chapel has instead a fresco with Madonna and Four Saints from 1351 by one Master from Feltre. The church, among others, houses the tombs of Pietro Alighieri, son of Dante, and Francesca Petrarca, daughter of the poet Francesco.

- The Loggia dei Cavalieri, an example of Treviso's Romanesque influenced by Byzantine forms. It was built under the podestà Andrea da Perugia (1276) as a place for meetings, talks and games, although reserved only to the higher classes.

- Piazza dei Signori (Lords' Square), with the Palazzo di Podestà (later 15th century).

- Church of San Nicolò, a mix of 13th century Venetian Romanesque and French Gothic elements. The interior has a nave and two aisles, with five apsed chapels. It houses important frescoes by Tommaso da Modena, depicting St. Romuald, St. Agnes and the Redemptor and St. Jerome in His Study. Also the Glorious Mysteries of Santo Peranda can be seen. Noteworthy is also the fresco of St. Christopher on the eastern side of the church, which is the most ancient depiction in glass in Europe.

- The Cathedral, dedicated to St. Peter. It was once a small church built in the Late Roman era, to which later were added a crypt and the Santissimo and Malchiostro Chapels (1520). After the numerous later restorations, only the gate remains of the original Roman edifice. The interior houses works by Il Pordenone and Titian (Malchiostro Annunciation) among others. The edifice has seven domes, five over the nave and two closing the chapels.

- Palazzo dei Trecento, built in the 13th - 14th centuries.

- Piazza Rinaldi. It is the seat of three palaces of the Rinaldi family, the first built in the 12th century after their flight from Frederick Barbarossa. The second, with unusual ogival arches in the loggia of the first floor, is from the 15th century. The third was added in the 18th century.

- Ponte di Pria (Stone Bridge), at the confluence of the Canal Grande and the Buranelli Channels.

- Monte di pietà and the Cappella dei Rettori. The Monte di Pietà was founded to house Jewish moneylenders. On the second floor is the Cappella dei Rettori, a lay hall for meetings, with frescoes by Pozzoserrato.