<Back to Index>

This page is sponsored by:

PAGE SPONSOR

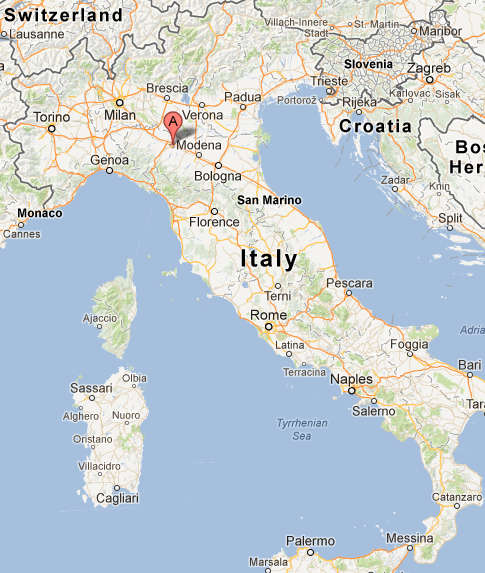

Lodi (Lombard: Lòd) is a city and comune in Lombardy, northern Italy, on the right bank of the River Adda. It is the capital of the province of Lodi.

Lodi was a Celtic village; in Roman times it was called in Latin Laus Pompeia (probably in honor of the consul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo) and was known also because its position allowed many Gauls of Gallia Cisalpina to obtain Roman citizenship. It was in an important position where a vital Roman road crossed the River Adda.

Lodi became the see of a diocese in the 3rd century and its first bishop, Saint Bassianus (San Bassiano) is the patron saint of the town.

A free commune around 1000, it fiercely resisted the Milanese, who destroyed it in 1111. The old town corresponds to the modern Lodi Vecchio. Frederick Barbarossa rebuilt it on its current location in 1158.

Starting from 1220, the Lodigiani (inhabitants of Lodi) spent some decades in realizing an important work of hydraulic engineering: a system of miles and miles of artificial rivers and channels (called Consorzio di Muzza) was created in order to give water to the countryside, turning some arid areas into one of the (still now) most important agricultural areas of the region.

Starting from the 14th century Lodi was ruled by the Visconti family, who built a castle here. In 1423, the antipope John XXIII launched the bull by which he convened the Council of Constance from the Duomo of Lodi. The council would mark the end of the Great Schism.

In 1454 representatives from all the regional states of Italy met in Lodi to sign the treaty known as the peace of Lodi, by which they intended to work in the direction of Italian unification, but this peace lasted only 40 years.

The town was then ruled by the Sforza family, France, Spain, Austria. In 1786 it became the eponymous capital of a province that between 1815 and 1859 would have included Crema.

On 10 May 1796, in the first major battle of his career as a general, the young Napoleon Bonaparte defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Lodi. In the second half of the 19th century, Lodi begun to expand outside the city walls, boosted by economic expansion and the construction of a network of railway lines that followed the reunification of Italy.

- Piazza della Vittoria, listed by the Italian Touring Club among the Most Beautiful Squares in Italy. Featuring porticoes on all its four sides, it includes the Basilica della Vergine Assunta and the Broletto (Town Hall).

- Piazza Broletto, with a Verona marble baptismal font dating to the 14th century.

- Church of the Beata Vergine Incoronata, considered one of the masterworks of the Lombard Renaissance.

- Church of San Francesco, built in 1280 - 1307.

- Church of San Lorenzo. It has a nave and two aisles, with frescoes by Callisto Piazza.

- Church of Santa Maria Maddalena, the best example of Baroque architecture in the city. The original Romanesque structure dated to 1162, but was remade in the early 18th century. The interior is on a single nave with side chapels, featuring, among the several artworks, frescoes by Carlo Innocenzo Carloni and a Deposition attributed to Robert De Longe.

- Church of Sant' Agnese, in Lombard Gothic style (14th cneutry). It includes the Galliani Polyptych by Alberto Piazza (1520), and has, on the façade, a rose window decorated with polychrome majolica.

- Church of San Filippo Neri, in Roccoco style.

- Palazzo Vescovile (Bishopric Palace), of medieval origin but rebuilt in the 18th century.

- Church of San Cristoforo, designed by Pellegrino Tibaldi.

- Visconti Castle (Torrione), a medieval castle now partially destroyed.

- Palazzo Mozzanica (15th century)

Parma (Emilian: Pärma) is a city in the Italian region of Emilia - Romagna famous for its prosciutto, cheese, architecture and surrounding countryside. This is the home of the University of Parma, one of the oldest universities in the world. Parma is divided into two parts by the little stream with the same name. Parma's Etruscan name was adapted by Romans to describe the round shield called Parma.

The Italian poet Attilio Bertolucci (born in a hamlet in the countryside) wrote: "As a capital city it had to have a river. As a little capital it received a stream, which is often dry". The district on the far side of the river is Oltretorrente.

Parma was already a built-up area in the Bronze Age. It has been verified by now that in the current position of the city rose a terramare. The "terramare" (marl earth) were ancient villages in structural wood on pile - dwelling built according to a defined scheme and squared form, built on the dry land, generally in proximity of the rivers. During this age (among the 1500 BC and the 800 BC) the first necropolises (placed where stand the present-day Piazza Duomo and Millstone Square) rose also.

The city was most probably founded and named by the Etruscans, for a parma (circular shield) was a Latin borrowing, as were many Roman terms for particular arms, and Parmeal, Parmni and Parmnial are names that appear in Etruscan inscriptions. Diodorus Siculus (XXII, 2,2; XXVIII, 2,1) reported that the Romans had changed their rectangular shields for round ones, imitating the Etruscans. Whether the Etruscan encampment was so named because it was round, like a shield, or whether its situation was a shield against the Gauls to the north, is uncertain.

The Roman colony was founded in 183 BC, together with Mutina (Modena); 2,000 families were settled. Parma had a certain importance as a road hub over the Via Aemilia and the Via Claudia. It had a forum, in what is today the central Garibaldi Square. In 44 BC, the city was destroyed, and Augustus rebuilt it. During the Roman Empire, it gained the title of Julia for its loyalty to the imperial house.

The city was subsequently sacked by Attila, and later given by the barbarian king Odoacer to his fellows. During the Gothic War, however, Totila destroyed it. It was then part of the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna (changing name to Chrysopolis, "Golden City", probably due to the presence of the imperial treasury) and, from 569, of the Lombard Kingdom of Italy. During the Middle Ages, Parma became an important stage of the Via Francigena, the main road connecting Rome to Northern Europe; several castles, hospitals and inns were built in the following centuries to host the increasing number of pilgrims who passed by Parma and Fidenza, following the Apennines via Collecchio, Berceto and the Corchia ranges before descending the Passo della Cisa into Tuscany, heading finally south toward Rome.

Under the Frankish rule, Parma became the capital of a county (774). Like most northern Italian cities, it was nominally a part of the Holy Roman Empire created by Charlemagne, but locally ruled by its bishops, the first being Guibodus. In the subsequent struggles between the Papacy and the Empire, Parma was usually a member of the Imperial party. Two of its bishops became antipopes: Càdalo, founder of the cathedral, as Honorius II); and Guibert, as Clement III). An almost independent commune was created around 1140; a treaty between Parma and Piacenza of 1149 is the earliest document of a comune headed by consuls. After the Peace of Constance (1183) confirmed the Italian communes' rights of self governance, long - standing quarrels with the neighboring communes of Reggio Emilia, Piacenza and Cremona became harsher, with the aim of controlling the vital trading line over the Po River.

The struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines was a feature of Parma too. In 1213, her podestà was the Guelph Rambertino Buvalelli. Then, after a long stance alongside the emperors, the Papist families of the city gained control in 1248. The city was besieged in 1247 – 48 by Emperor Frederick II, who was however crushed in the battle that ensued.

Parma fell under the control of Milan in 1341. After a short - lived period of independence under the Terzi family (1404 – 1409), the Sforzas imposed their rule (1440 – 1449) through their associated families of Pallavicino, Rossi, Sanvitale and Da Correggio. These created a kind of new feudalism, building towers and castles throughout the city and the land. These fiefs evolved into truly independent states: the Landi governed the higher Taro's valley from 1257 to 1682. The Pallavicino seignory extended over the eastern part of today's province, with the capital in Busseto. Parma's territories were an exception for Northern Italy, as its feudal subdivision frequently continued until more recent years. For example, Solignano was a Pallavicino family possession until 1805, and San Secondo belonged to the Rossi well into the 19th century.

Between the 14th and the 15th centuries, Parma was at the center of the Italian Wars. The Battle of Fornovo was fought in its territory. The French held the city in 1500 – 1521, with a short Papal parenthesis in 1512 – 1515. After the foreigners were expelled, Parma belonged to the Papal States until 1545.

In that year the Farnese pope, Paul III, detached Parma and Piacenza from the Papal States and gave them as a duchy for his illegitimate son, Pier Luigi Farnese, whose descendants ruled in Parma until 1731, when Antonio Farnese (1679 – 1731), last male of the Farnese line, died. In the Treaty of London (1718) it was promulgated that the heir to the duchy would be Elisabeth Farnese's elder son with Philip V of Spain, Don Carlos. In 1731, the fifteen year old Don Carlos became Charles I Duke of Parma and Piacenza, at the death of his childless great uncle Antonio Farnese. In 1734, Charles I conquered the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, and was crowned as the King of Naples and Sicily on 3 July 1735, leaving the Duchy of Parma to his brother Philip (Filippo I di Borbone - Parma).

In 1594 a constitution was promulgated, the University enhanced and the Nobles' College founded. The war to reduce the barons' power continued for several years: in 1612 Barbara Sanseverino was executed in the central square of Parma, together with six other nobles charged of plotting against the duke. At the end of the 17th century, after the defeat of Pallavicini (1588) and Landi (1682) the Farnese duke could finally hold with firm hand all Parmense territories. The castle of the Sanseverino in Colorno was turned into a luxurious summer palace by Ferdinando Bibiena.

In 1731 the combined Duchy of Parma and Piacenza was given to the House of Bourbon in a diplomatic shuffle of the European dynastic politics that were played out in Italy. Under the new rulers, however, it faced a certain decadence. In 1734 all the outstanding art collections of the duke's palaces of Parma, Colorno and Sala Baganza were moved to Naples.

Parma was under French influence after the Peace of Aachen (1748). Parma became a modern state with the energetic action of prime minister Guillaume du Tillot. He created the bases for a modern industry and fought strenuously against the church's privileges. The city lived a period of particular splendor: the Biblioteca Palatina (Palatine Library), the Archaeological Museum, the Picture Gallery and the Botanical Garden were founded, together with the Royal Printing Works directed by Giambattista Bodoni.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1802 – 1814), Parma was part of the Taro Département. Under its French name Parme, it was also created a duché grand-fief de l'Empire for Charles - François Lebrun, duc de Plaisance, the Emperor's Arch - Treasurer, on 24 April 1808 (extinguished 1926).

After its restoration by the 1814 – 15 Vienna Congress, the Risorgimento's upheavals had no fertile ground in the tranquil duchy. In 1847, after Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma's death, it passed again to the Bourbons, the last of whom was stabbed in the city and left it to his Widow, Luisa Maria of Berry. On September 15, 1859 the dynasty was declared deposed, and Parma entered in the newly formed provinces of Emilia under Luigi Carlo Farini. With the plebiscite of 1860 the former duchy became part of the unified Kingdom of Italy.

The loss of the capital role provoked an economical and social crisis in Parma. It started to recover its role of industrial prominence after the connection with Piacenza and Bologna of 1859, and with Fornovo and Suzzara in 1883. Trade unions were strong in the city, in which a famous General Strike was declared from May 1 to June 6, 1908. The struggle with Fascism lived its most dramatic moment in August 1922, when the regime officer Italo Balbo attempted to enter in the popular quarter of Oltretorrente. The citizens organized into the Arditi del Popolo ("People's assaulters") and pushed back the squadristi. This episode is considered the first example of Resistance in Italy.

During World War II, Parma was a strong center of partisan resistance. The train station and marshalling yards were targets for high altitude bombing by the Allies in the spring of 1944. Much of the Palazzo della Pilotta — situated not far (half a mile) from the train station — was destroyed. Along with it also Teatro Farnese and part of Biblioteca Palatina were destroyed by Allied bombs. Several other monuments were also damaged: Palazzo del Giardino, Steccata church, San Giovanni church, Palazzo Ducale, Paganini theater and the monument to Verdi. However Parma did not see widespread destruction during the war. Parma was liberated of the German occupation (1943 – 1945) on April 26, 1945 by the partisan resistance and troops of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force.

- The Romanesque Cathedral houses both 12th century sculpture by Benedetto Antelami and a 16th century fresco masterpiece by Antonio da Correggio.

- The Baptistery, adjacent to the cathedral was begun in 1196 by Antelami.

- The abbey church of Saint John the Evangelist (San Giovanni Evangelista), was originally constructed in the 10th century behind the Cathedral's apse, but had to be rebuilt in 1498 and 1510 after a fire. It has a late Mannerist facade and a bell tower designed by Simone Moschino), and retains its Latin cross plan, a nave and two aisles. In 1520 – 1522, Correggio frescoed the dome with the Vision of St. John the Evangelist, a highly influential fresco which heralded illusionistic perspective in the decoration of church ceilings. Bernardo Falconi designed a putto in the high altar. Also the cloisters and the ancient Benedictine grocery are noteworthy. The library has books from the 15th and 16th centuries.

- Sanctuary of Santa Maria della Steccata.

- The Benedictine Monastery of San Paolo, founded in the 11th century. It houses precious frescoes by Correggio, in the so-called Camera di San Paolo (1519 – 1520), and Alessandro Araldi.

- The Gothic church of San Francesco del Prato (13th century). From Napoleonic era to 1990s it was the city's jail, for which the 16 windows in the facade were opened. The original rose windows (1461) has 16 rays, which, in the medieval tradition, represented the house of God. The Oratory of the Concezione houses frescoes by Michelangelo Anselmi and Francesco Rondani. The altarpiece by Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli is now in the National Gallery of Parma.

- Church of Santa Croce, dating to the early 12th century. The original edifice, in Romanesque style, had a nave and two aisles with a semicircular apse. This was renovated first in 1415 and again in 1635 – 1666, with the heightening of the aisles and nave, the addition of a presbytery, a dome and of the chapel of St. Joseph. The frescoes in the nave (by Giovanni Maria Conti della Camera, Francesco Reti and Antonio Lombardi) date to this period.

- Church of San Sepolcro, built in 1275 over a preexisting religious edifice. The church was largely renovated in 1506, 1603 and 1701, when the side on the Via Emilia was remade in Neoclassicist style. The church has a nave with side chapels. The Baroque bell tower was built in 1616, the cups being finished in 1753. Annexed is the former monastery of the Regular Canons of the Lateran, dating to 1493 – 1495.

- Church of Santa Maria del Quartiere (1604 – 1619), characterized by a usual hexagonal plan. The cupola is decorated with frescoes by Pier Antonio Bernabei and his pupils.

- The Palazzo della Pilotta (1583). It houses the Academy of Fine Arts with artists of the School of Parma, the Palatine Library, the National Gallery, the Archaeological Museum, the Bodoni Museum and the Farnese Theatre.

- The Ducal Palace, built from 1561 for Duke Ottavio Farnese on a design by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola. Built on the former Sforza castle area, it was enlarged in the 17th – 18th centuries. It includes the Palazzo Eucherio Sanvitale, with interesting decorations dating from the 16th centuries and attributed to Gianfrancesco d'Agrate, and a fresco by Parmigianino. Annexed is the Ducal Park also by Vignola. It was turned into a French style garden in 1749.

- The Palazzo del Comune, built in 1627.

- The Palazzo del Governatore ("Governor's Palace"), dating from the 13th century.

- The Bishop's Palace (1055).

- Ospedale Vecchio ("Old Hospital"), created in 1250 and later renovated in Renaissance times. It is now home to the State Archives and to the Communal Library.

- The Teatro Farnese was constructed in 1618 – 1619 by Giovan Battista Aleotti, totally in wood. It was commissioned by Duke Ranuccio I for the visit of Cosimo I de' Medici.

- The Cittadella, a large fortress erected in the 16th century by order of Duke Alessandro Farnese, close to the old walls.

- The Pons Lapidis (also known as Roman Bridge or Theoderic's Bridge), a Roman structure in stone dating from Augustus reign.

- The Orto Botanico di Parma is a botanical garden maintained by the University of Parma.

- The Teatro Regio ("Royal Theatre"), built in 1821 – 1829 by Nicola Bettoli. It has a Neo-Classical facade and a porch with double window order. It is the city's opera house.

- The Auditorium Niccolò Paganini, designed by Renzo Piano.

- The Museum House of Arturo Toscanini, where the famous musician was born.

- Museo Lombardi. It exhibits a prestigious collection of art and historical items regarding Maria Luigia of Hapsburg and her first husband Napoleon Bonaparte; important works and documents concerning the Duchy of Parma in the 18th and 19th centuries are also kept by the Museum.