<Back to Index>

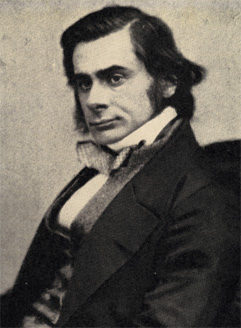

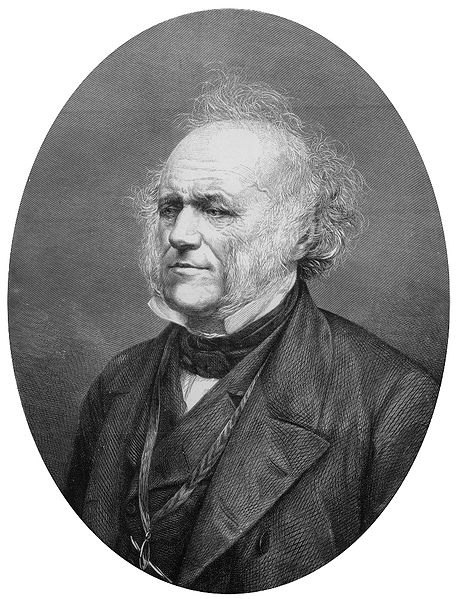

- Lawyer and Geologist Charles Lyell, 1797

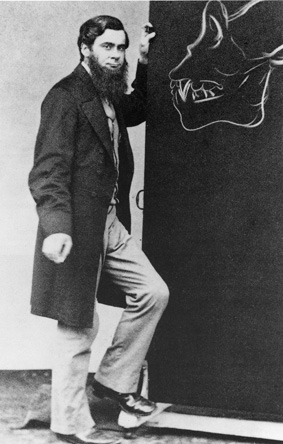

- Biologist and Anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley, 1825

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, Kt FRS (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day. He is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularized James Hutton's concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by the same processes still in operation today. Lyell was a close and influential friend of Charles Darwin.

Lyell was born in Scotland about 15 miles north of Dundee in Kinnordy, near Kirriemuir in Forfarshire (now in Angus). He was the eldest of ten children. Lyell's father, also named Charles, was a lawyer and botanist of minor repute: it was he who first exposed his son to the study of nature.

The house / place of his birth is located in the northwest of the Central Lowlands in the valley of the Highland Boundary Fault. Round the house, in the rift valley, is farmland, but within a short distance to the northwest, on the other side of the fault, are the Grampian Mountains in the Highlands. His family's second home was in a completely different geological and ecological area: he spent much of his childhood at Bartley Lodge in the New Forest, England.

Lyell entered Exeter College, Oxford, in 1816, and attended William Buckland's lectures. He graduated B.A. second class in classics, December 1819, and M.A. 1821. After graduation he took up law as a profession, entering Lincoln's Inn in 1820. He completed a circuit through rural England, where he could observe geological phenomena. In 1821 he attended Robert Jameson's lectures in Edinburgh, and visited Gideon Mantell at Lewes, in Sussex. In 1823 he was elected joint secretary of the Geological Society. As his eyesight began to deteriorate, he turned to geology as a full time profession. His first paper, "On a recent formation of freshwater limestone in Forfarshire", was presented in 1822. By 1827, he had abandoned law and embarked on a geological career that would result in fame and the general acceptance of uniformitarianism, a working out of the idea proposed by James Hutton a few decades earlier.

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner of Bonn, daughter of Leonard Horner (1785 – 1864), also associated with the Geological Society of London. The new couple spent their honeymoon in Switzerland and Italy on a geological tour of the area.

During the 1840s, Lyell traveled to the United States and Canada, and wrote two popular travel - and - geology books: Travels in North America (1845) and A Second Visit to the United States (1849). After the Great Chicago Fire, Lyell was one of the first to donate books to help found the Chicago Public Library. In 1866, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Lyell's wife died in 1873, and two years later Lyell himself died as he was revising the twelfth edition of Principles. He is buried in Westminster Abbey. Lyell was knighted (Kt), and later made a baronet (Bt), which is an hereditary honor. He was awarded the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1858 and the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society in 1866. The crater Lyell on the Moon and a crater on Mars were named in his honor. In addition, Mount Lyell in western Tasmania, Australia, located in a profitable mining area, bears Lyell’s name. The ancient jawless fish Cephalaspis lyelli, which dwelt in the lochs of Scotland, was named by Louis Agassiz in honor of Lyell.

Lyell had private means, and earned further income as an author. He came from a prosperous family, worked briefly as a lawyer in the 1820s, and held the post of Professor of Geology at King's College London in the 1830s. From 1830 onward his books provided both income and fame. Each of his three major books was a work continually in progress. All three went through multiple editions during his lifetime, although many of his friends (such as Darwin) thought the first edition of the Principles was the best written. Lyell used each edition to incorporate additional material, rearrange existing material, and revisit old conclusions in light of new evidence.

Principles of Geology, Lyell's first book, was also his most famous, most influential, and most important. First published in three volumes in 1830 – 33, it established Lyell's credentials as an important geological theorist and propounded the doctrine of uniformitarianism. It was a work of synthesis, backed by his own personal observations on his travels.

The central argument in Principles was that the present is the key to the past – a concept of the Scottish Enlightenment which David Hume had stated as "all inferences from experience suppose ... that the future will resemble the past", and James Hutton had described when he wrote in 1788 that "from what has actually been, we have data for concluding with regard to that which is to happen thereafter." Geological remains from the distant past can, and should, be explained by reference to geological processes now in operation and thus directly observable. Lyell's interpretation of geologic change as the steady accumulation of minute changes over enormously long spans of time was a powerful influence on the young Charles Darwin. Lyell asked Robert FitzRoy, captain of HMS Beagle, to search for erratic boulders on the survey voyage of the Beagle, and just before it set out FitzRoy gave Darwin Volume 1 of the first edition of Lyell's Principles. When the Beagle made its first stop ashore at St Jago, Darwin found rock formations which seen "through Lyell's eyes" gave him a revolutionary insight into the geological history of the island, an insight he applied throughout his travels.

While in South America Darwin received Volume 2 which considered the ideas of Lamarck in some detail. Lyell rejected Lamarck's idea of organic evolution, proposing instead "Centers of Creation" to explain diversity and territory of species. However, as discussed below, many of his letters show he was fairly open to the idea of evolution. In geology Darwin was very much Lyell's disciple, and brought back observations and his own original theorizing, including ideas about the formation of atolls, which supported Lyell's uniformitarianism. On the return of the Beagle (October 1836) Lyell invited Darwin to dinner and from then on they were close friends. Although Darwin discussed evolutionary ideas with him from 1842, Lyell continued to reject evolution in each of the first nine editions of the Principles. He encouraged Darwin to publish, and following the 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species, Lyell finally offered a tepid endorsement of evolution in the tenth edition of Principles.

Elements of Geology began as the fourth volume of the third edition of Principles: Lyell intended the book to act as a suitable field guide for students of geology. The systematic, factual description of geological formations of different ages contained in Principles grew so unwieldy, however, that Lyell split it off as the Elements in 1838. The book went through six editions, eventually growing to two volumes and ceasing to be the inexpensive, portable handbook that Lyell had originally envisioned. Late in his career, therefore, Lyell produced a condensed version titled Student's Elements of Geology that fulfilled the original purpose.

Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man brought together Lyell's views on three key themes from the geology of the Quaternary Period of Earth history: glaciers, evolution and the age of the human race. First published in 1863, it went through three editions that year, with a fourth and final edition appearing in 1873. The book was widely regarded as a disappointment because of Lyell's equivocal treatment of evolution. Lyell, a devout Christian, had great difficulty reconciling his beliefs with natural selection.

Lyell's geological interests ranged from volcanoes and geological dynamics through stratigraphy, paleontology and glaciology to topics that would now be classified as prehistoric archaeology and paleoanthropology. He is best known, however, for his role in popularizing the doctrine of uniformitarianism.

From 1830 to 1833 his multi volume Principles of Geology was published. The work's subtitle was "An attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth's surface by reference to causes now in operation", and this explains Lyell's impact on science. He drew his explanations from field studies conducted directly before he went to work on the founding geology text. He was, along with the earlier John Playfair, the major advocate of James Hutton's idea of uniformitarianism, that the earth was shaped entirely by slow moving forces still in operation today, acting over a very long period of time. This was in contrast to catastrophism, a geologic idea of abrupt changes, which had been adapted in England to support belief in Noah's flood. Lyell saw himself as "the spiritual savior of geology, freeing the science from the old dispensation of Moses." The two terms, uniformitarianism and catastrophism, were both coined by William Whewell; in 1866 R. Grove suggested the simpler term continuity for Lyell's view, but the old terms persisted. In various revised editions (12 in all, through 1872), Principles of Geology was the most influential geological work in the middle of the 19th century, and did much to put geology on a modern footing. For his efforts he was knighted in 1848, then made a baronet in 1864.

Lyell noted the “economic advantages” that geological surveys could provide, citing their felicity in mineral rich countries and provinces. Modern surveys, like the U.S. Geological Survey, map and exhibit the natural resources within the country. So, in endorsing surveys, as well as advancing the study of geology, Lyell helped to forward the business of modern extractive industries, such as the coal and oil industry.

Before the work of Lyell, phenomena such as earthquakes were understood by the destruction that they brought. One of the contributions that Lyell made in Principles was to explain the cause of earthquakes. Lyell, in contrast focused on recent earthquakes (150 yrs), evidenced by surface irregularities such as faults, fissures, stratigraphic displacements and depressions.

Lyell's work on volcanoes focused largely on Vesuvius and Etna, both of which he had earlier studied. His conclusions supported gradual building of volcanoes, so-called "backed up - building", as opposed to the upheaval argument supported by other geologists.

Lyell's most important specific work was in the field of stratigraphy. From May 1828, until February 1829, he traveled with Roderick Impey Murchison (1792 – 1871) to the south of France (Auvergne volcanic district) and to Italy. In these areas he concluded that the recent strata (rock layers) could be categorized according to the number and proportion of marine shells encased within. Based on this he proposed dividing the Tertiary period into three parts, which he named the Pliocene, Miocene and Eocene.

In Principles of Geology (first edition, vol. 3, Ch. 2, 1833) Lyell proposed that icebergs could be the means of transport for erratics. During periods of global warming, ice breaks off the poles and floats across submerged continents, carrying debris with it, he conjectured. When the iceberg melts, it rains down sediments upon the land. Because this theory could account for the presence of diluvium, the word drift became the preferred term for the loose, unsorted material, today called till. Furthermore, Lyell believed that the accumulation of fine angular particles covering much of the world (today called loess) was a deposit settled from mountain flood water. Today some of Lyell's mechanisms for geologic processes have been disproven, though many have stood the test of time. His observational methods and general analytical framework remain in use today as foundational principles in geology.

Lyell first received a copy of one of Lamarck's books from Mantell in 1827, when he was on circuit. He thanked Mantell in a letter which includes this enthusiastic passage:

- "I devoured Lamark... his theories delighted me... I am glad that he has been courageous enough and logical enough to admit that his argument, if pushed as far as it must go, if worth anything, would prove that men may have come from the Ourang - Outang. But after all, what changes species may really undergo!... That the Earth is quite as old as he supposes, has long been my creed..."

In the second volume of the first edition of Principles Lyell explicitly rejected the mechanism of Lamark on the transmutation of species, and was doubtful whether species were mutable. However, privately, in letters, he was more open to the possibility of evolution:

- "If I had stated... the possibility of the introduction or origination of fresh species being a natural, in contradistinction to a miraculous process, I should have raised a host of prejudices against me, which are unfortunately opposed at every step to any philosopher who attempts to address the public on these mysterious subjects".

This letter makes it clear that his equivocation on evolution was, at least at first, a deliberate tactic. As a result of his letters and, no doubt, personal conversations, Huxley and Haeckel were convinced that, at the time he wrote Principles, he believed new species had arisen by natural methods. Both Whewell and Sedgwick wrote worried letters to him about this.

Later, Darwin became a close personal friend, and Lyell was one of the first scientists to support On the Origin of Species, though he did not subscribe to all its contents. Lyell was also a friend of Darwin's closest colleagues, Hooker and Huxley, but unlike them he struggled to square his religious beliefs with evolution. This inner struggle has been much commented on. He had particular difficulty in believing in natural selection as the main motive force in evolution.

Lyell and Hooker were instrumental in arranging the peaceful co-publication of the theory of natural selection by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in 1858: each had arrived at the theory independently. Lyell's data on stratigraphy were important because Darwin thought that populations of an organism changed slowly, requiring "geologic time".

Although Lyell did not publicly accept evolution (descent with modification) at the time of writing the Principles, after the Darwin – Wallace papers and the Origin Lyell wrote in his notebook:

- May 3, 1860: "Mr. Darwin has written a work which will constitute an era in geology & natural history to show that... the descendants of common parents may become in the course of ages so unlike each other as to be entitled to rank as a distinct species, from each other or from some of their progenitors".

Lyell's acceptance of natural selection, Darwin's proposed mechanism for evolution, was equivocal, and came in the tenth edition of Principles. The Antiquity of Man (published in early February 1863, just before Huxley's Man's place in nature) drew these comments from Darwin to Huxley:

- "I am fearfully disappointed at Lyell's excessive caution" and "The book is a mere 'digest' ".

Quite strong remarks: no doubt Darwin resented Lyell's repeated suggestion that he owed a lot to Lamarck, whom he (Darwin) had always specifically rejected. Darwin's daughter Henrietta (Etty) wrote to her father: "Is it fair that Lyell always calls your theory a modification of Lamarck's?"

In other respects Antiquity was a success. It sold well, and it "shattered the tacit agreement that mankind should be the sole preserve of theologians and historians". But when Lyell wrote that it remained a profound mystery how the huge gulf between man and beast could be bridged, Darwin wrote "Oh!" in the margin of his copy.

Thomas Henry Huxley PC FRS (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist (anatomist), known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

Huxley's famous 1860 debate with Samuel Wilberforce was a key moment in the wider acceptance of evolution, and in his own career. Huxley had been planning to leave Oxford on the previous day, but, after an encounter with Robert Chambers, the author of Vestiges, he changed his mind and decided to join the debate. Wilberforce was coached by Richard Owen, against whom Huxley also debated whether humans were closely related to apes.

Huxley was slow to accept some of Darwin's ideas, such as gradualism, and was undecided about natural selection, but despite this he was wholehearted in his public support of Darwin. He was instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, and fought against the more extreme versions of religious tradition.

In 1869 Huxley coined the term 'agnostic' to describe his own views on theology, a term whose use has continued to the present day.

Huxley had little formal schooling and taught himself almost everything he knew. He became perhaps the finest comparative anatomist of the latter 19th century. He worked on invertebrates, clarifying relationships between groups previously little understood. Later, he worked on vertebrates, especially on the relationship between apes and humans. After comparing Archaeopteryx with Compsognathus, he concluded that birds evolved from small carnivorous dinosaurs, a theory widely accepted today.

The tendency has been for this fine anatomical work to be overshadowed by his energetic and controversial activity in favor of evolution, and by his extensive public work on scientific education, both of which had significant effects on society in Britain and elsewhere.

Thomas Henry Huxley was born in Ealing, then moved to a village in Middlesex. He was the second youngest of eight children of George Huxley and Rachel Withers. Like some other British scientists of the nineteenth century such as Alfred Russel Wallace, Huxley was brought up in a literate middle class family which had fallen on hard times. His father was a mathematics teacher at Ealing School until it closed, putting the family into financial difficulties. As a result, Thomas left school at age 10, after only two years of formal schooling.

Despite this unenviable start, Huxley was determined to educate himself. He became one of the great autodidacts of the nineteenth century. At first he read Thomas Carlyle, James Hutton's Geology, Hamilton's Logic. In his teens he taught himself German, eventually becoming fluent and used by Charles Darwin as a translator of scientific material in German. He learned Latin and enough Greek to read Aristotle in the original.

Later on, as a young adult, he made himself an expert of knowledge on the topic of first on invertebrates, and later on vertebrates, all self taught. He was skilled in drawing and did many of the illustrations for his publications on marine invertebrates. In his later debates and writing on science and religion his grasp of theology was better than most of his clerical opponents. Huxley, a boy who left school at ten, became one of the most knowledgeable men in Britain.

He was apprenticed for short periods to several medical practitioners: at 13 to his brother - in - law John Cooke in Coventry, who passed him on to Thomas Chandler, notable for his experiments using mesmerism for medical purposes. Chandler's practice was in London's Rotherhithe amid the squalor endured by the Dickensian poor. Here Thomas would have seen poverty, crime and rampant disease at its worst. Next, another brother - in - law took him on: John Salt, his eldest sister's husband. Now 16, Huxley entered Sydenham College (behind University College Hospital), a cut price anatomy school whose founder Marshall Hall discovered the reflex arc. All this time Huxley continued his program of reading, which more than made up for his lack of formal schooling.

A year later, buoyed by excellent results and a silver medal prize in the Apothecaries' yearly competition, Huxley was admitted to study at Charing Cross Hospital, where he obtained a small scholarship. At Charing Cross, he was taught by the Scot, Thomas Wharton Jones, Professor of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery at University College London. Jones had been Robert Knox's assistant when Knox bought cadavers from Burke and Hare. The young Wharton Jones, who acted as go - between, was exonerated of crime, but thought it best to leave Scotland. He was a fine teacher, up - to - date in physiology and also an ophthalmic surgeon. In 1845, under Wharton Jones' guidance, Huxley published his first scientific paper demonstrating the existence of a hitherto unrecognized layer in the inner sheath of hairs, a layer that has been known since as Huxley's layer. No doubt remembering this, and of course knowing his merit, later in life Huxley organized a pension for his old tutor.

At twenty he passed his First M.B. examination at the University of London, winning the gold medal for anatomy and physiology. However, he did not present himself for the final (2nd M.B.) exams and consequently did not qualify with a university degree. His apprenticeships and exam results formed a sufficient basis for his application to the Royal Navy.

Aged 20, Huxley was too young to apply to the Royal College of Surgeons for a license to practice, yet he was 'deep in debt'. So, at a friend's suggestion, he applied for an appointment in the Royal Navy. He had references on character and certificates showing the time spent on his apprenticeship and on requirements such as dissection and pharmacy. Sir William Burnett, the Physician General of the Navy, interviewed him and arranged for the College of Surgeons to test his competence (by means of a viva voce).

Finally Huxley was made Assistant Surgeon ('surgeon's mate') to HMS Rattlesnake, about to start for a voyage of discovery and surveying to New Guinea and Australia. The Rattlesnake left England on 3 December 1846 and, once they had arrived in the southern hemisphere, Huxley devoted his time to the study of marine invertebrates. He began to send details of his discoveries back to England, where publication was arranged by Edward Forbes FRS (who had also been a pupil of Knox). Both before and after the voyage Forbes was something of a mentor to Huxley.

Huxley's paper "On the anatomy and the affinities of the family of Medusae" was published in 1849 by the Royal Society in its Philosophical Transactions. Huxley united the Hydroid and Sertularian polyps with the Medusae to form a class to which he subsequently gave the name of Hydrozoa. The connection he made was that all the members of the class consisted of two cell layers, enclosing a central cavity or stomach. This is characteristic of the phylum now called the Cnidaria. He compared this feature to the serous and mucous structures of embryos of higher animals. When at last he got a grant from the Royal Society for the printing of plates, Huxley was able to summarize this work in The Oceanic Hydrozoa, published by the Ray Society in 1859.

The value of Huxley's work was recognized and, on returning to England in 1850, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the following year, at the age of twenty - six, he not only received the Royal Society Medal but was also elected to the Council. He met Joseph Dalton Hooker and John Tyndall, who remained his lifelong friends. The Admiralty retained him as a nominal assistant surgeon, so he might work on the specimens he collected and the observations he made during the voyage of the Rattlesnake. He solved the problem of Appendicularia, whose place in the animal kingdom Johannes Peter Müller had found himself wholly unable to assign. It and the Ascidians are both, as Huxley showed, tunicates, today regarded as a sister group to the vertebrates in the phylum Chordata. Other papers on the morphology of the cephalopods and on brachiopods and rotifers are also noteworthy. The Rattlesnake's official naturalist, John MacGillivray, did some work on botany, and proved surprisingly good at notating Australian aboriginal languages. He wrote up the voyage in the standard Victorian two volume format.

Huxley effectively resigned from the navy (by refusing to return to active service) and, in July 1854, he became Professor of Natural History at the Royal School of Mines and naturalist to the British Geological Survey in the following year. In addition, he was Fullerian Professor at the Royal Institution 1855 – 58 and 1865 – 67; Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons 1863 – 69; President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1869 – 1870; President of the Royal Society 1883 – 85; Inspector of Fisheries 1881 – 85; and President of the Marine Biological Association 1884 - 1890.

The thirty - one years during which Huxley occupied the chair of natural history at the Royal School of Mines included work on vertebrate palaeontology and on many projects to advance the place of science in British life. Huxley retired in 1885, after a bout of depressive illness which started in 1884. He resigned the Presidency of the Royal Society in mid term, the Inspectorship of Fisheries, and his chair (as soon as he decently could) and took six month's leave. His pension was a fairly handsome £1500 a year.

In 1890, he moved from London to Eastbourne where he edited the nine volumes of his Collected Essays. In 1894 he heard of Eugene Dubois' discovery in Java of the remains of Pithecanthropus erectus (now known as Homo erectus). Finally, in 1895, he died of a heart attack (after contracting influenza and pneumonia), and was buried in North London at St Marylebone. This small family plot had been purchased upon the death of his beloved youngest son Noel, who died of scarlet fever in 1860; Huxley's wife is also buried there. No invitations were sent out, but two hundred people turned up for the ceremony; they included Hooker, Flower, Foster, Lankester, Joseph Lister and, apparently, Henry James.

From 1870 onward, Huxley was to some extent drawn away from scientific research by the claims of public duty. He served on eight Royal Commissions, from 1862 to 1884. From 1871 – 80 he was a Secretary of the Royal Society and from 1883 – 85 he was President. He was President of the Geological Society from 1868 – 70. In 1870, he was President of the British Association at Liverpool and, in the same year was elected a member of the newly constituted London School Board. He was the leading person among those who reformed the Royal Society, persuaded government about science, and established scientific education in British schools and universities. Before him, science was mostly a gentleman's occupation; after him, science was a profession.

He was awarded the highest honors then open to British men of science. The Royal Society, who had elected him as Fellow when he was 25 (1851), awarded him the Royal Medal the next year (1852), a year before Charles Darwin got the same award. He was the youngest biologist to receive such recognition. Then later in life came the Copley Medal in 1888 and the Darwin Medal in 1894; the Geological Society awarded him the Wollaston Medal in 1876; the Linnean Society awarded him the Linnean Medal in 1890. There were many other elections and appointments to eminent scientific bodies; these and his many academic awards are listed in the Life and Letters. He turned down many other appointments, notably the Linacre chair in zoology at Oxford and the Mastership of University College, Oxford.

In 1873 the King of Sweden made Huxley, Hooker and Tyndall Knights of the Order of the North Star: they could wear the insignia but not use the title in Britain. Huxley collected many honorary memberships of foreign societies, academic awards and honorary doctorates from Britain and Germany.

As recognition of his many public services he was given a pension by the state, and was appointed Privy Councillor in 1892.

There was so much achievement in his life that it seems extraordinary that he was given no award by the British state until late in life. In this he did better than Darwin, who got no award of any kind from the state. (Darwin's proposed knighthood was vetoed by ecclesiastical advisors, including Wilberforce.) Perhaps Huxley had commented too often on his dislike of honors, or perhaps his many assaults on the traditional beliefs of organized religion made enemies in the establishment — he had vigorous debates in print with Prime Ministers Disraeli, Gladstone and Arthur Balfour, and his relationship with Lord Salisbury was less than tranquil.

Huxley was for about thirty years evolution's most effective advocate, and for some Huxley was "the premier advocate of science in the nineteenth century [for] the whole English speaking world".

Though he had many admirers and disciples, his retirement and later death left British zoology somewhat bereft of leadership. He had, directly or indirectly, guided the careers and appointments of the next generation, but none were of his stature. The loss of Francis Balfour in 1882, climbing the Alps just after he was appointed to a chair at Cambridge, was a tragedy. Huxley thought he was "the only man who can carry out my work": the deaths of Balfour and W.K. Clifford were "the greatest losses to science in our time".

The first half of Huxley's career as a palaeontologist is marked by a rather strange predilection for 'persistent types', in which he seemed to argue that evolutionary advancement (in the sense of major new groups of animals and plants) was rare or absent in the Phanerozoic. In the same vein, he tended to push the origin of major groups such as birds and mammals back into the Palaeozoic era, and to claim that no order of plants had ever gone extinct.

Much paper has been consumed by historians of science ruminating on this strange and somewhat unclear idea. Huxley was wrong to pitch the loss of orders in the Phanerozoic as low as 7%, and he did not estimate the number of new orders which evolved. Persistent types sat rather uncomfortably next to Darwin's more fluid ideas; despite his intelligence, it took Huxley a surprisingly long time to appreciate some of the implications of evolution. However, gradually Huxley moved away from this conservative style of thinking as his understanding of palaeontology, and the discipline itself, developed.

Huxley's detailed anatomical work was, as always, first rate and productive. His work on fossil fish shows his distinctive approach: whereas pre - Darwinian naturalists collected, identified and classified, Huxley worked mainly to reveal the evolutionary relationships between groups.

The lobed - finned fish (such as coelacanths and lung fish) have paired appendages whose internal skeleton is attached to the shoulder or pelvis by a single bone, the humerus or femur. His interest in these fish brought him close to the origin of tetrapods, one of the most important areas of vertebrate palaeontology.

The study of fossil reptiles led to his demonstrating the fundamental affinity of birds and reptiles, which he united under the title of Sauropsida. His papers on Archaeopteryx and the origin of birds were of great interest then and still are.

Apart from his interest in persuading the world that man was a primate, and had descended from the same stock as the apes, Huxley did little work on mammals, with one exception. On his tour of America Huxley was shown the remarkable series of fossil horses, discovered by O.C. Marsh, in Yale's Peabody Museum. Marsh was part palaeontologist, part robber baron, a man who had hunted buffalo and met Red Cloud (in 1874). Funded by his uncle George Peabody, Marsh had made some remarkable discoveries: the huge Cretaceous aquatic bird Hesperornis, and the dinosaur footprints along the Connecticut River were worth the trip by themselves, but the horse fossils were really special.

The collection at that time went from the small four - toed forest dwelling Orohippus from the Eocene through three - toed species such as Miohippus to species more like the modern horse. By looking at their teeth he could see that, as the size grew larger and the toes reduced, the teeth changed from those of a browser to those of a grazer. All such changes could be explained by a general alteration in habitat from forest to grassland. And, we now know, that is what did happen over large areas of North America from the Eocene to the Pleistocene: the ultimate causative agent was global temperature reduction (Paleocene - Eocene thermal maximum). The modern account of the evolution of the horse has many other members, and the overall appearance of the tree of descent is more like a bush than a straight line.

The horse series also strongly suggested that the process was gradual, and that the origin of the modern horse lay in North America, not in Eurasia. If so, then something must have happened to horses in North America, since none were there when Europeans arrived. The experience was enough for Huxley to give credence to Darwin's gradualism, and to introduce the story of the horse into his lecture series.

Huxley was originally not persuaded of 'development theory' as evolution was once called. We can see that in his savage review of Robert Chambers' Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a book which contained some quite pertinent arguments in favor of evolution. Huxley had also rejected Lamarck's theory of transmutation, on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to support it. All this skepticism was brought together in a lecture to the Royal Institution, which made Darwin anxious enough to set about an effort to change young Huxley's mind. It was the kind of thing Darwin did with his closest scientific friends, but he must have had some particular intuition about Huxley, who was from all accounts a most impressive person even as a young man.

Huxley was therefore one of the small group who knew about Darwin's ideas before they were published (the group included Joseph Dalton Hooker and Charles Lyell). The first publication by Darwin of his ideas came when Wallace sent Darwin his famous paper on natural selection, which was presented by Lyell and Hooker to the Linnean Society in 1858 alongside excerpts from Darwin's notebook and a Darwin letter to Asa Gray. Huxley's famous response to the idea of natural selection was "How extremely stupid not to have thought of that!" However, the correctness of natural selection as the main mechanism for evolution was to lie permanently in Huxley's mental pending tray. He never conclusively made up his mind about it, though he did admit it was a hypothesis which was a good working basis.

Logically speaking, the prior question was whether evolution had taken place at all. It is to this question that much of Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species was devoted. Its publication in 1859 completely convinced Huxley of evolution and it was this and no doubt his admiration of Darwin's way of amassing and using evidence that formed the basis of his support for Darwin in the debates that followed the book's publication.

Huxley's support started with his anonymous favorable review of the Origin in the Times for 26 December 1859, and continued with articles in several periodicals, and in a lecture at the Royal Institution in February 1860. At the same time, Richard Owen, whilst writing an extremely hostile anonymous review of the Origin in the Edinburgh Review, also primed Samuel Wilberforce who wrote one in the Quarterly Review, running to 17,000 words. The authorship of this latter review was not known for sure until Wilberforce's son wrote his biography. So it can be said that, just as Darwin groomed Huxley, so Owen groomed Wilberforce; and both the proxies fought public battles on behalf of their principals as much as themselves. Though we do not know the exact words of the Oxford debate, we do know what Huxley thought of the review in the Quarterly:

- "Since Lord Brougham assailed Dr Young, the world has seen no such specimen of the insolence of a shallow pretender to a Master in Science as this remarkable production, in which one of the most exact of observers, most cautious of reasoners, and most candid of expositors, of this or any other age, is held up to scorn as a "flighty" person, who endeavours "to prop up his utterly rotten fabric of guess and speculation," and whose "mode of dealing with nature" is reprobated as "utterly dishonourable to Natural Science."

- If I confine my retrospect of the reception of the 'Origin of Species' to a twelvemonth, or thereabouts, from the time of its publication, I do not recollect anything quite so foolish and unmannerly as the Quarterly Review article...

"I am Darwin's bulldog" said Huxley, and it is apt; the second half of Darwin's life was lived mainly within his family, and the younger, combative Huxley operated mainly out in the world at large. A letter from THH to Ernst Haeckel (2 November 1871) goes "The dogs have been snapping at [Darwin's] heels too much of late."

Famously, Huxley responded to Wilberforce in the debate at the British Association meeting, on Saturday 30 June 1860 at the Oxford University Museum. Huxley's presence there had been encouraged on the previous evening when he met Robert Chambers, the Scottish publisher and author of "Vestiges", who was walking the streets of Oxford in a dispirited state, and begged for assistance. The debate followed the presentation of a paper by John William Draper, and was chaired by Darwins's former botany tutor John Stevens Henslow. Darwin's theory was opposed by the Lord Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, and those supporting Darwin included Huxley and their mutual friends Hooker and Lubbock. The platform featured Brodie and Professor Beale, and Robert FitzRoy, who had been captain of HMS Beagle during Darwin's voyage, spoke against Darwin.

Wilberforce had a track record against evolution as far back as the previous Oxford B.A. meeting in 1847 when he attacked Chambers' Vestiges. For the more challenging task of opposing the Origin, and the implication that man descended from apes, he had been assiduously coached by Richard Owen – Owen stayed with him the night before the debate. On the day Wilberforce repeated some of the arguments from his Quarterly Review article (written but not yet published), then ventured onto slippery ground. His famous jibe at Huxley (as to whether Huxley was descended from an ape on his mother's side or his father's side) was probably unplanned, and certainly unwise. Huxley's reply to the effect that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his great talents to suppress debate — the exact wording is not certain — was widely recounted in pamphlets and a spoof play.

The letters of Alfred Newton include one to his brother giving an eye witness account of the debate, and written less than a month afterwards. Other eyewitnesses, with one or two exceptions (Hooker especially thought he had made the best points), give similar accounts, at varying dates after the event. The general view was and still is that Huxley got much the better of the exchange though Wilberforce himself thought he had done quite well. In the absence of a verbatim report differing perceptions are difficult to judge fairly; Huxley wrote a detailed account for Darwin, a letter which does not survive; however, a letter to his friend Frederick Daniel Dyster does survive with an account just three months after the event.

One effect of the debate was to increase hugely Huxley's visibility among educated people, through the accounts in newspapers and periodicals. Another consequence was to alert him to the importance of public debate: a lesson he never forgot. A third effect was to serve notice that Darwinian ideas could not be easily dismissed: on the contrary, they would be vigorously defended against orthodox authority. A fourth effect was to promote professionalism in science, with its implied need for scientific education. A fifth consequence was indirect: as Wilberforce had feared, a defense of evolution did undermine literal belief in the Old Testament, especially the Book of Genesis. Many of the liberal clergy at the meeting were quite pleased with the outcome of the debate; they were supporters, perhaps, of the controversial Essays and Reviews. Thus both on the side of science, and on the side of religion, the debate was important, and its outcome significant.

That Huxley and Wilberforce remained on courteous terms after the debate (and able to work together on projects such as the Metropolitan Board of Education) says something about both men, whereas Huxley and Owen were never reconciled.

For nearly a decade his work was directed mainly to the relationship of man to the apes. This led him directly into a clash with Richard Owen, a man widely disliked for his behavior whilst also being admired for his capability. The struggle was to culminate in some severe defeats for Owen. Huxley's Croonian Lecture, delivered before the Royal Society in 1858 on The Theory of the Vertebrate Skull was the start. In this, he rejected Owen's theory that the bones of the skull and the spine were homologous, an opinion previously held by Goethe and Lorenz Oken.

From 1860 – 63 Huxley developed his ideas, presenting them in lectures to working men, students and the general public, followed by publication. Also in 1862 a series of talks to working men was printed lecture by lecture as pamphlets, later bound up as a little green book; the first copies went on sale in December. Other lectures grew into Huxley's most famous work Evidence as to Man's place in Nature (1863) where he addressed the key issues long before Charles Darwin published his Descent of Man in 1871.

Although Darwin did not publish his Descent of Man until 1871, the general debate on this topic had started years before (there was even a precursor debate in the 18th century between Monboddo and Buffon). Darwin had dropped a hint when, in the conclusion to the Origin, he wrote: "In the distant future... light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history". Not so distant, as it turned out. A key event had already occurred in 1857 when Richard Owen presented (to the Linnean Society) his theory that man was marked off from all other mammals by possessing features of the brain peculiar to the genus Homo. Having reached this opinion, Owen separated man from all other mammals in a subclass of its own. No other biologist held such an extreme view. Darwin reacted "Man... as distinct from a chimpanzee [as] an ape from a platypus... I cannot swallow that!" Neither could Huxley, who was able to demonstrate that Owen's idea was completely wrong.

The subject was raised at the 1860 BA Oxford meeting, when Huxley flatly contradicted Owen, and promised a later demonstration of the facts. In fact, a number of demonstrations were held in London and the provinces. In 1862 at the Cambridge meeting of the B.A. Huxley's friend William Flower gave a public dissection to show that the same structures (the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle and hippocampus minor) were indeed present in apes. The debate was widely publicized, and parodied as the Great Hippocampus Question. It was seen as one of Owen's greatest blunders, revealing Huxley as not only dangerous in debate, but also a better anatomist.

Owen conceded that there was something that could be called a hippocampus minor in the apes, but stated that it was much less developed and that such a presence did not detract from the overall distinction of simple brain size.

Huxley's ideas on this topic were summed up in January 1861 in the first issue (new series) of his own journal, the Natural History Review: "the most violent scientific paper he had ever composed". This paper was reprinted in 1863 as chapter 2 of Man's Place in Nature, with an addendum giving his account of the Owen / Huxley controversy about the ape brain. In his Collected Essays this addendum was edited out.

The extended argument on the ape brain, partly in debate and partly in print, backed by dissections and demonstrations, was a landmark in Huxley's career. It was highly important in asserting his dominance of comparative anatomy, and in the long run more influential in establishing evolution among biologists than was the debate with Wilberforce. It also marked the start of Owen's decline in the esteem of his fellow biologists.

The following was written by Huxley to Rolleston before the 1861 BA meeting:

- "My dear Rolleston... The obstinate reiteration of erroneous assertions can only be nullified by as persistent an appeal to facts; and I greatly regret that my engagements do not permit me to be present at the British Association in order to assist personally at what, I believe, will be the seventh public demonstration during the past twelve months of the untruth of the three assertions, that the posterior lobe of the cerebrum, the posterior cornu of the lateral ventricle, and the hippocampus minor, are peculiar to man and do not exist in the apes. I shall be obliged if you will read this letter to the Section" Yours faithfully, Thos. H. Huxley.

During those years there was also work on human fossil anatomy and anthropology. In 1862 he examined the Neanderthal skull - cap, which had been discovered in 1857. It was the first pre - sapiens discovery of a fossil man, and it was immediately clear to him that the brain case was surprisingly large.

Perhaps less productive was his work on physical anthropology, a topic which fascinated the Victorians. Huxley classified the human races into nine categories, and discussed them under four headings as: Australoid, Negroid, Xanthocroic and Mongoloid types. Such classifications depended mainly on appearance and anatomical characteristics. Modern molecular and genome analysis has shown that the genetic diversity of man in sub - Saharan Africa is greater than exists in the entire rest of the human race.

Huxley was certainly not slavish in his dealings with Darwin. As shown in every biography, they had quite different and rather complementary characters. Important also, Darwin was a field naturalist, but Huxley was an anatomist, so there was a difference in their experience of nature. Lastly, Darwin's views on science were different from Huxley's views. For Darwin, natural selection was the best way to explain evolution because it explained a huge range of natural history facts and observations: it solved problems. Huxley, on the other hand, was an empiricist who trusted what he could see, and some things are not easily seen. With this in mind, one can appreciate the debate between them, Darwin writing his letters, Huxley never going quite so far as to say he thought Darwin was right.

Huxley's reservations on natural selection were of the type "until selection and breeding can be seen to give rise to varieties which are infertile with each other, natural selection cannot be proved". Huxley's position on selection was agnostic; yet he gave no credence to any other theory.

Darwin's part in the discussion came mostly in letters, as was his wont, along the lines: "The empirical evidence you call for is both impossible in practical terms, and in any event unnecessary. It's the same as asking to see every step in the transformation (or the splitting) of one species into another. My way so many issues are clarified and problems solved; no other theory does nearly so well".

Huxley's reservation, as Helena Cronin has so aptly remarked, was contagious: "it spread itself for years among all kinds of doubters of Darwinism". One reason for this doubt was that comparative anatomy could address the question of descent, but not the question of mechanism.

In November 1864 Huxley succeeded in launching a dining club, the X Club, like - minded people working to advance the cause of science; not surprisingly, the club consisted of most of his closest friends. There were nine members, who decided at their first meeting that there should be no more. The members were: Huxley, John Tyndall, J.D. Hooker, John Lubbock (banker, biologist and neighbor of Darwin), Herbert Spencer (social philosopher and sub-editor of the Economist), William Spottiswoode (mathematician and the Queen's Printer), Thomas Hirst (Professor of Physics at University College London), Edward Frankland (the new Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution) and George Busk, zoologist and palaeontologist (formerly surgeon for HMS Dreadnought). All except Spencer were Fellows of the Royal Society. Tyndall was a particularly close friend; for many years they met regularly and discussed issues of the day. On more than one occasion Huxley joined Tyndall in the latter's trips into the Alps and helped with his investigations in glaciology.

There were also some quite significant X-Club satellites such as William Flower and George Rolleston, (Huxley protegés), and liberal clergyman Arthur Stanley, the Dean of Westminster. Guests such as Charles Darwin and Hermann von Helmholtz were entertained from time to time.

They would dine early on first Thursdays at a hotel, planning what to do; high on the agenda was to change the way the Royal Society Council did business. It was no coincidence that the Council met later that same evening. First item for the Xs was to get the Copley Medal for Darwin, which they managed after quite a struggle.

The next step was to acquire a journal to spread their ideas. This was the weekly Reader, which they bought, revamped and redirected. Huxley had already become part owner of the Natural History Review bolstered by the support of Lubbock, Rolleston, Busk and Carpenter (X-clubbers and satellites). The journal was switched to pro - Darwinian lines and relaunched in January 1861. After a stream of good articles the NHR failed after four years; but it had helped at a critical time for the establishment of evolution. The Reader also failed, despite its broader appeal which included art and literature as well as science. The periodical market was quite crowded at the time, but most probably the critical factor was Huxley's time; he was simply over committed, and could not afford to hire full time editors. This occurred often in his life: Huxley took on too many ventures, and was not so astute as Darwin at getting others to do work for him.

However, the experience gained with the Reader was put to good use when the X Club put their weight behind the founding of Nature in 1869. This time no mistakes were made: above all there was a permanent editor (though not full time), Norman Lockyer, who served until 1919, a year before his death. In 1925, to celebrate his centenary, Nature issued a supplement devoted to Huxley.

The peak of the X Club's influence was from 1873 – 85 as Hooker, Spottiswoode and Huxley were Presidents of the Royal Society in succession. Spencer resigned in 1889 after a dispute with Huxley over state support for science. After 1892 it was just an excuse for the surviving members to meet. Hooker died in 1911, and Lubbock (now Lord Avebury) was the last surviving member.

Huxley was also an active member of the Metaphysical Society, which ran from 1869 – 80. It was formed around a nucleus of clergy and expanded to include all kinds of opinions. Tyndall and Huxley later joined The Club (founded by Dr. Johnson) when they could be sure that Owen would not turn up.

When Huxley himself was young there were virtually no degrees in British universities in the biological sciences and few courses. Most biologists of his day were either self taught, or took medical degrees. When he retired there were established chairs in biological disciplines in most universities, and a broad consensus on the curricula to be followed. Huxley was the single most influential person in this transformation.

In the early 1870s the Royal School of Mines moved to new quarters in South Kensington; ultimately it would become one of the constituent parts of Imperial College London. The move gave Huxley the chance to give more prominence to laboratory work in biology teaching, an idea suggested by practice in German universities. In the main, the method was based on the use of carefully chosen types, and depended on the dissection of anatomy, supplemented by microscopy, museum specimens and some elementary physiology at the hands of Foster.

The typical day would start with Huxley lecturing at 9am, followed by a program of laboratory work supervised by his demonstrators. Huxley's demonstrators were picked men — all became leaders of biology in Britain in later life, spreading Huxley's ideas as well as their own. Michael Foster became Professor of Physiology at Cambridge; E. Ray Lankester became Jodrell Professor of Zoology at University College London (1875 – 91), Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Oxford (1891 – 98) and Director of the Natural History Museum (1898 – 1907); S.H. Vines became Professor of Botany at Cambridge; W.T. Thiselton - Dyer became Hooker's successor at Kew (he was already Hooker's son - in - law!); T. Jeffery Parker became Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at University College, Cardiff; and William Rutherford became the Professor of Physiology at Edinburgh. William Flower, Conservator to the Hunterian Museum, and THH's assistant in many dissections, became Sir William Flower, Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy and, later, Director of the Natural History Museum. It's a remarkable list of disciples, especially when contrasted with Owen who, in a longer professional life than Huxley, left no disciples at all. "No one fact tells so strongly against Owen... as that he has never reared one pupil or follower".

Huxley's courses for students were so much narrower than the man himself that many were bewildered by the contrast: "The teaching of zoology by use of selected animal types has come in for much criticism"; Looking back in 1914 to his time as a student, Sir Arthur Shipley said "[Although] Darwin's later works all dealt with living organisms, yet our obsession was with the dead, with bodies preserved, and cut into the most refined slices". E.W MacBride said "Huxley... would persist in looking at animals as material structures and not as living, active beings; in a word... he was a necrologist. To put it simply, Huxley preferred to teach what he had actually seen with his own eyes.

This largely morphological program of comparative anatomy remained at the core of most biological education for a hundred years until the advent of cell and molecular biology and interest in evolutionary ecology forced a fundamental rethink. It is an interesting fact that the methods of the field naturalists who led the way in developing the theory of evolution (Darwin, Wallace, Fritz Müller, Henry Bates) were scarcely represented at all in Huxley's program. Ecological investigation of life in its environment was virtually non existent, and theory, evolutionary or otherwise, was at a discount. Michael Ruse finds no mention of evolution or Darwinism in any of the exams set by Huxley, and confirms the lecture content based on two complete sets of lecture notes.

Since Darwin, Wallace and Bates did not hold teaching posts at any stage of their adult careers (and Műller never returned from Brazil) the imbalance in Huxley's program went uncorrected. It is surely strange that Huxley's courses did not contain an account of the evidence collected by those naturalists of life in the tropics; evidence which they had found so convincing, and which caused their views on evolution by natural selection to be so similar. Desmond suggests that "[biology] had to be simple, synthetic and assimilable [because] it was to train teachers and had no other heuristic function". That must be part of the reason; indeed it does help to explain the stultifying nature of much school biology. But zoology as taught at all levels became far too much the product of one man.

Huxley was comfortable with comparative anatomy, at which he was the greatest master of the day. He was not an all - round naturalist like Darwin, who had shown clearly enough how to weave together detailed factual information and subtle arguments across the vast web of life. Huxley chose, in his teaching (and to some extent in his research) to take a more straightforward course, concentrating on his personal strengths.

Huxley was also a major influence in the direction taken by British schools: in November 1870 he was voted onto the London School Board. In primary schooling, he advocated a wide range of disciplines, similar to what is taught today: reading, writing, arithmetic, art, science, music, etc. In secondary education he recommended two years of basic liberal studies followed by two years of some upper division work, focusing on a more specific area of study. A practical example is his famous essay On a piece of chalk, first published in Macmillan's Magazine in London, 1868. The piece reconstructs the geological history of Britain, from a simple piece of chalk and demonstrates science as "organized common sense".

Huxley supported the reading of the Bible in schools. This may seem out of step with his agnostic convictions, but he believed that the Bible's significant moral teachings and superb use of language were relevant to English life. "I do not advocate burning your ship to get rid of the cockroaches". However, what Huxley proposed was to create an edited version of the Bible, shorn of "shortcomings and errors... statements to which men of science absolutely and entirely demur... These tender children [should] not be taught that which you do not yourselves believe". The Board voted against his idea, but it also voted against the idea that public money should be used to support students attending church schools. Vigorous debate took place on such points, and the debates were minuted in detail. Huxley said "I will never be a party to enabling the State to sweep the children of this country into denominational schools". The Act of Parliament which founded board schools permitted the reading of the Bible, but did not permit any denominational doctrine to be taught.

It may be right to see Huxley's life and work as contributing to the secularization of British society which gradually occurred over the following century. Ernst Mayr said "It can hardly be doubted that [biology] has helped to undermine traditional beliefs and value systems" — and Huxley more than anyone else was responsible for this trend in Britain. Some modern Christian apologists consider Huxley the father of antitheism, though he himself maintained that he was an agnostic, not an atheist. He was, however, a lifelong and determined opponent of almost all organized religion throughout his life, especially the "Roman Church... carefully calculated for the destruction of all that is highest in the moral nature, in the intellectual freedom, and in the political freedom of mankind". Vladimir Lenin remarked (in Materialism and empirio - criticism) "In Huxley's case... agnosticism serves as a fig - leaf for materialism".

Huxley's interest in education went still further than school and university classrooms; he made a great effort to reach interested adults of all kinds: after all, he himself was largely self educated. There were his lecture courses for working men, many of which were published afterwards, and there was the use he made of journalism, partly to earn money but mostly to reach out to the literate public. For most of his adult life he wrote for periodicals — the Westminster Review, the Saturday Review, the Reader, the Pall Mall Gazette, Macmillan's Magazine, the Contemporary Review. Germany was still ahead in formal science education, but interested people in Victorian Britain could use their initiative and find out what was going on by reading periodicals and using the lending libraries.

In 1868 Huxley became Principal of the South London Working Men's College in Blackfriars Road. The moving spirit was a portmanteau worker, Wm. Rossiter, who did most of the work; the funds were put up mainly by F.D. Maurice's Christian Socialists. At sixpence for a course and a penny for a lecture by Huxley, this was some bargain; and so was the free library organized by the college, an idea which was widely copied. Huxley thought, and said, that the men who attended were as good as any country squire.

The technique of printing his more popular lectures in periodicals which were sold to the general public was extremely effective. A good example was The physical basis of life, a lecture given in Edinburgh on 8 November 1868. Its theme — that vital action is nothing more than "the result of the molecular forces of the protoplasm which displays it" — shocked the audience, though that was nothing compared to the uproar when it was published in the Fortnightly Review for February 1869. John Morley, the editor, said "No article that had appeared in any periodical for a generation had caused such a sensation". The issue was reprinted seven times and protoplasm became a household word; Punch added 'Professor Protoplasm' to his other soubriquets.

The topic had been stimulated by Huxley seeing the cytoplasmic streaming in plant cells, which is indeed a sensational sight. For these audiences Huxley's claim that this activity should not be explained by words such as vitality, but by the working of its constituent chemicals, was surprising and shocking. Today we would perhaps emphasize the extraordinary structural arrangement of those chemicals as the key to understanding what cells do, but little of that was known in the nineteenth century.

When the Archbishop of York thought this 'new philosophy' was based on Auguste Comte's positivism, Huxley corrected him: "Comte's philosophy [is just] Catholicism minus Christianity" (Huxley 1893 vol 1 of Collected Essays Methods & Results 156). A later version was "[positivism is] sheer Popery with M. Comte in the chair of St Peter, and with the names of the saints changed". (lecture on The scientific aspects of positivism Huxley 1870 Lay Sermons, Addresses and Reviews p149). Huxley's dismissal of positivism damaged it so severely that Comte's ideas withered in Britain.

During his life, and especially in the last ten years after retirement, Huxley wrote on many issues relating to the humanities.

Perhaps the best known of these topics is Evolution and Ethics, which deals with the question of whether biology has anything particular to say about moral philosophy. Both Huxley and his grandson Julian Huxley gave Romanes Lectures on this theme. For a start, Huxley dismisses religion as a source of moral authority. Next, he believes the mental characteristics of man are as much a product of evolution as the physical aspects. Thus, our emotions, our intellect, our tendency to prefer living in groups and spend resources on raising our young are part and parcel of our evolution, and therefore inherited.

Despite this, the details of our values and ethics are not inherited: they are partly determined by our culture, and partly chosen by ourselves. Morality and duty are often at war with natural instincts; ethics cannot be derived from the struggle for existence. It is therefore our responsibility to make ethical choices. This seems to put Huxley as a compatibilist in the Free Will vs Determinism debate. In this argument Huxley is diametrically opposed to his old friend Herbert Spencer.

- "Of moral purpose I see not a trace in nature. That is an article of exclusively human manufacture." letter THH to W. Platt Ball.

Huxley's dissection of Rousseau's views on man and society is another example of his later work. The essay undermines Rousseau's ideas on man as a preliminary to undermining his ideas on the ownership of property. Characteristic is:

- "The doctrine that all men are, in any sense, or have been, at any time, free and equal, is an utterly baseless fiction."

Huxley's method of argumentation (his strategy and tactics of persuasion in speech and print) is itself much studied. His career included controversial debates with scientists, clerics and politicians; persuasive discussions with Royal Commissions and other public bodies; lectures and articles for the general public, and a mass of detailed letter writing to friends and other correspondents. A large number of textbooks have excerpted his prose for anthologies.

Huxley worked on ten Royal and other commissions (titles somewhat shortened here). The Royal Commission is the senior investigative forum in the British constitution. A rough analysis shows that five commissions involved science and scientific education; three involved medicine and three involved fisheries. Several involve difficult ethical and legal issues. All deal with possible changes to law and / or administrative practice.

In 1855, he married Henrietta Anne Heathorn (1825 – 1915), an English émigrée whom he had met in Sydney. They kept correspondence until he was able to send for her. They had five daughters and three sons:

- Noel Huxley (1856 – 60), died aged 4.

- Jessie Oriana Huxley (1856 – 1927), married architect Fred Waller in 1877.

- Marian Huxley (1859 – 87), married artist John Collier in 1879.

- Leonard Huxley, (1860 – 1933) author.

- Rachel Huxley (1862 – 1934) married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884; he died 1895.

- Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863 – 1940), married Harold Roller, traveled Europe as a singer.

- Henry Huxley (1865 – 1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

- Ethel Huxley (1866 – 1941), married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

Huxley's relationship with his relatives and children were genial by the standards of the day — so long as they lived their lives in an honorable manner, which some did not. After his mother, his eldest sister Lizzie was the most important person in his life until his own marriage. He remained on good terms with his children, more than can be said of many Victorian fathers. This excerpt from a letter to Jessie, his eldest daughter is full of affection:

- "Dearest Jess, You are a badly used young person — you are; and nothing short of that conviction would get a letter out of your still worse used Pater, the bête noir of whose existence is letter writing. Catch me discussing the Afghan question with you, you little pepper - pot! No, not if I know it..." [goes on nevertheless to give strong opinions of the Afghans, at that time causing plenty of trouble to the Indian Empire — Second Anglo - Afghan War] "There, you plague — ever your affec. Daddy, THH." (letter Dec 7th 1878, Huxley L 1900)

Huxley's descendants include children of Leonard Huxley:

- Sir Julian Huxley FRS was the first Director of UNESCO and a notable evolutionary biologist and humanist.

- Aldous Huxley was a famous author (Brave New World 1932, Eyeless in Gaza 1936, The Doors of Perception 1954).

- Sir Andrew Huxley OM FRS won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963. He was the second Huxley to become President of the Royal Society.

Other significant descendants of Huxley, such as Sir Crispin Tickell, were treated in the Huxley family.

Biographers have sometimes noted the occurrence of mental illness in the Huxley family. His father became "sunk in worse than childish imbecility of mind", and later died in Barming Asylum; brother George suffered from "extreme mental anxiety" and died in 1863 leaving serious debts. Brother James, a well known psychiatrist and Superintendent of Kent County Asylum, was at 55 "as near mad as any sane man can be"; and there is more. His favorite daughter, the artistically talented Mady (Marian), who became the first wife of artist John Collier, was troubled by mental illness for years. She died of pneumonia in her mid twenties.

About Huxley himself we have a more complete record. As a young apprentice to a medical practitioner, aged thirteen or fourteen, Huxley was taken to watch a post mortem dissection. Afterwards he sank into a 'deep lethargy' and though Huxley ascribed this to dissection poisoning, Bibby and others may be right to suspect that emotional shock precipitated the depression. Huxley recuperated on a farm, looking thin and ill.

The next episode we know of in Huxley's life when he suffered a debilitating depression was on the third voyage of HMS Rattlesnake in 1848. Huxley had further periods of depression at the end of 1871, and again in 1873. Finally, in 1884 he sank into another depression, and this time it precipitated his decision to retire in 1885, at the age of only 60. This is enough to indicate the way depression (or perhaps a moderate bi-polar disorder) interfered with his life, yet unlike some of the other family members, he was able to function extremely well at other times.

The problems continued sporadically into the third generation. Two of Leonard's sons suffered serious depression: Trevennen committed suicide in 1914 and Julian suffered a breakdown in 1913, and five more later in life.

Darwin's ideas and Huxley's controversies gave rise to many cartoons and satires. It was the debate about man's place in nature that roused such widespread comment: cartoons are so numerous as to be almost impossible to count; Darwin's head on a monkey's body is one of the visual clichés of the age. The "Great Hippocampus Question" attracted particular attention:

- Monkeyana (Punch vol 40, 18 May 1861). Signed 'Gorilla', this

turned out to be by Sir Philip Egerton MP, amateur naturalist, fossil

fish collector and — Richard Owen's patron! Last two stanzas:

Next HUXLEY replies

That OWEN he lies

And garbles his Latin quotation;

That his facts are not new,

His mistakes not a few,

Detrimental to his reputation.

To twice slay the slain

By dint of the Brain

(Thus HUXLEY concludes his review)

Is but labour in vain,

unproductive of gain,

And so I shall bid you "Adieu"! - The Gorilla's Dilemma (Punch 1862, vol 43 p164). First two lines:

Say am I a man or a brother,

Or only an anthropoid ape? - Report of a sad case recently tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley. Lord Mayor asks whether either side is known to the police:

(Tom Huxley's 'low set' included Hooker 'in the green and vegetable line' and 'Charlie Darwin, the pigeon - fancier'; Owen's 'crib in Bloomsbury' was the British Museum, of which Natural History was but one department.)Policeman X — Huxley, your Worship, I take to be a young hand, but very vicious; but Owen I have seen before. He got into trouble with an old bone man, called Mantell, who never could be off complaining as Owen prigged his bones. People did say that the old man never got over it, and Owen worritted him to death; but I don't think it was so bad as that. Hears as Owen takes the chair at a crib in Bloomsbury. I don't think it will be a harmonic meeting altogether. And Huxley hangs out in Jermyn Street.

- The Water Babies, a fairy tale for a land baby by Charles Kingsley (serialized in Macmillan's Magazine

1862 – 63, published in book form, with additions, in 1863). Kingsley had

been among first to give a favorable review to Darwin's On the Origin of Species, having "long since... learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species", and the story includes a satire on the reaction to Darwin's theory,

with the main scientific participants appearing, including Richard Owen

and Huxley. In 1892 Thomas Henry Huxley's five year old grandson Julian

saw the illustration by Edward Linley Sambourne and wrote his

grandfather a letter asking:

Huxley wrote back:Dear Grandpater – Have you seen a Waterbaby? Did you put it in a bottle? Did it wonder if it could get out? Could I see it some day? – Your loving Julian.

My dear Julian – I could never make sure about that Water Baby... My friend who wrote the story of the Water Baby was a very kind man and very clever. Perhaps he thought I could see as much in the water as he did – There are some people who see a great deal and some who see very little in the same things.

When you grow up I dare say you will be one of the great - deal seers, and see things more wonderful than the Water Babies where other folks can see nothing.