<Back to Index>

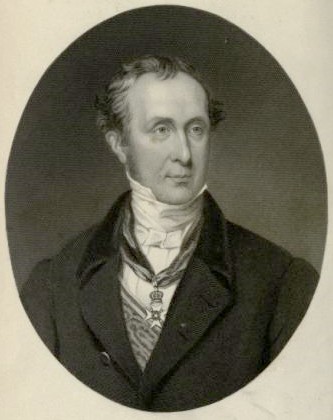

- Geologist Roderick Impey Murchison, 1792

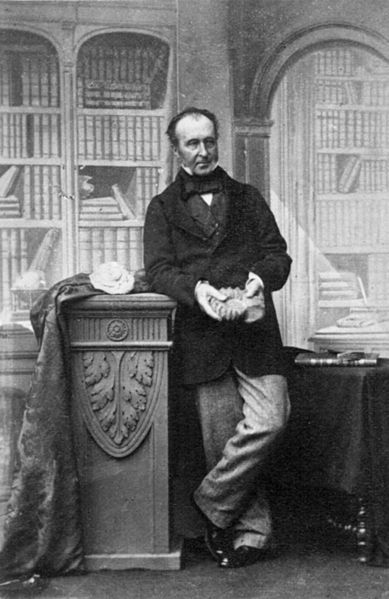

- Chemist John Henry Pepper, 1821

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet (22 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who first described and investigated the Silurian system.

Murchison was born at Tarradale House, Muir of Ord, Ross - shire, the son of Kenneth Murchison. His wealthy father died in 1796, when Roderick was 4 years old, and he was sent to Durham School 3 years later, and then the military college at Great Marlow to be trained for the army. In 1808 he landed with Wellesley in Galicia, and was present at the actions of Roliça and Vimeiro. Subsequently under Sir John Moore, he took part in the retreat to Corunna and the final battle there.

After eight years of service Murchison left the army, and married Charlotte Hugonin (8 April 1788 – 9 February 1869), the only daughter of General Hugonin, of Nursted House, Hampshire. Murchison and his wife spent two years in mainland Europe, particularly in Italy. They then settled in Barnard Castle, County Durham, England, in 1818 where Murchison made the acquaintance of Sir Humphry Davy. Davy urged Murchison to turn his energy to science, after hearing that he wasted his time riding to hounds and shooting. Murchison became fascinated by the young science of geology and joined the Geological Society of London, soon becoming one of its most active members. His colleagues there included Adam Sedgwick, William Conybeare, William Buckland, William Fitton, Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin.

Exploring with his wife, Murchison studied the geology of the south of England, devoting special attention to the rocks of the northwest of Sussex and the adjoining parts of Hampshire and Surrey, on which, aided by Fitton, he wrote his first scientific paper, read to the Geological Society of London in 1825. Turning his attention to Continental geology, he and Lyell explored the volcanic region of Auvergne, parts of southern France, northern Italy, Tyrol and Switzerland. A little later, with Sedgwick as his companion, Murchison attacked the difficult problem of the geological structure of the Alps. Their joint paper giving the results of their study is a classic in the literature of Alpine geology.

In 1831 he went to the border of England and Wales, to attempt to discover whether the greywacke rocks underlying the Old Red Sandstone could be grouped into a definite order of succession. The result was the establishment of the Silurian system under which were grouped, for the first time, a remarkable series of formations, each replete with distinctive organic remains other than and very different from those of the other rocks of England. These researches, together with descriptions of the coalfields and overlying formations in South Wales and the English border counties, were embodied in The Silurian System (1839).

The establishment of the Silurian system was followed by that of the Devonian system, an investigation in which Murchison assisted, both in the southwest of England and in the Rhineland. Soon afterwards Murchison projected an important geological campaign in Russia with the view of extending to that part of the Continent the classification he had succeeded in elaborating for the older rocks of western Europe. He was accompanied by Edouard de Verneuil (1805 – 1873) and Count Alexander von Keyserling (1815 – 1891), in conjunction with whom he produced a work on Russia and the Ural Mountains. The publication of this monograph in 1845 completes the first and most active half of Murchison’s scientific career.

In 1846 he was knighted, and in the same year he presided over the meeting of the British Association at Southampton. During the later years of his life a large part of his time was devoted to the affairs of the Royal Geographical Society, of which he was in 1830 one of the founders, and he was president 1843 - 1845, 1851 – 1853, 1856 – 1859 and 1862 - 1871. He served on the Royal Commission on the British Museum (1847 – 49).

The chief geological investigation of the last decade of his life was devoted to the Highlands of Scotland, where he wrongly believed he had succeeded in showing that the vast masses of crystalline schists, previously supposed to be part of what used to be termed the Primitive formations, were really not older than the Silurian period, for that underneath them lay beds of limestone and quartzite containing Lower Silurian (Cambrian) fossils. James Nicol recognized the fallacy in the Murchison's extant theory and propounded his own ideas, in the 1880s these were superseded by the correct theory of Charles Lapworth, which was corroborated by Benjamin Peach and John Horne. Their subsequent research showed that the infraposition of the fossiliferous rocks is not their original place, but had been brought about by a gigantic system of dislocations, whereby successive masses of the oldest gneisses, have been torn up from below and thrust bodily over the younger formations.

In 1855 Murchison was appointed director general of the British Geological Survey and director of the Royal School of Mines and the Museum of Practical Geology in Jermyn Street, London, in succession to Sir Henry De la Beche, who had been the first to hold these offices. Official routine now occupied much of his time, but he found opportunity for the Highland researches just alluded to, and also for preparing successive editions of his work Siluria (1854, ed. 5, 1872), which was meant to present the main features of the original Silurian System together with a digest of subsequent discoveries, particularly of those that showed the extension of the Silurian classification into other countries.

In 1863 he was made a KCB, and three years later was created a baronet. The learned societies of his own country bestowed their highest rewards upon him: the Royal Society gave him the Copley medal, the Geological Society its Wollaston medal, and the Royal Society of Edinburgh its Brisbane Medal. There was hardly a foreign scientific society of note without his name among its honorary members. The French Academy of Sciences awarded him the prix Cuvier, and elected him one of its eight foreign members in succession to Michael Faraday. In 1855, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

One of the closing public acts of Murchison’s life was the founding of a chair of geology and mineralogy at the University of Edinburgh. Under his will there was established the Murchison Medal and a geological fund (The Murchison Fund) to be awarded annually by the council of the Geological Society in London.

Murchison died in 1871, and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, London.

The crater Murchison on the Moon and at least fifteen geographical locations on Earth are named after him.

These include: Mount Murchison in the Mountaineer Range, Antarctica; Mount Murchison, just west of Squamish, British Columbia, Canada; tiny Murchison Island in the Queen Charlotte Islands in the same province; Murchison Falls (Uganda); and the Murchison River in Western Australia. Unusually, Murchison has two other rivers named after him in Western Australia: the Roderick River and the Impey River, both tributaries of the Murchison.

A memorial tablet of Murchison was installed on 3 November 2005, in front of School #9 in Perm. It consists of a stone base, irregular in form, about 2 meters long and bearing a dark stone plate with the inscription:

To Roderick Impey Murchison, Scottish geologist, explorer of Perm Krai, who gives to the last period of Paleozoic era the name of Perm.

The decision to perpetuate the explorer's name was accepted by the school administration and pupils in connection with a discussion to establish in Perm a pillar or an arch devoted to Roderick Murchison.

In 2009, the Ural - Scottish Society erected a memorial to Murchison on the banks of the Chusovaya River.

There is a commemorative 'blue plaque' on his residence in Barnard Castle (County Durham) at 21 Galgate.

John Henry "Professor" Pepper (17 June 1821 – 25 March 1900) was a British scientist and inventor who toured the English speaking world with his scientific demonstrations. He entertained the public, royalty, and fellow scientists with a wide range of technological innovations. He is primarily remembered for developing the projection technique known as Pepper's ghost, building a large scale version of the concept by Henry Dircks. He also oversaw the introduction of evening lectures at the Royal Polytechnic Institution and wrote several important science education books, one of which is regarded as a significant step towards the understanding of continental drift. While in Australia he tried unsuccessfully to make it rain using electrical conduction and large explosions.

Pepper was born in Westminster, London, and educated at King's College School. While there he became fascinated with the developments of science and in particular chemistry as taught by J.T. Cooper, an eminent chemist who developed the oxy-hydrogen microscope. Cooper acted as a mentor to Pepper, who would go on to become an assistant lecturer at the Granger School of Medicine at the age of 19. In around 1843 he was elected a Fellow of the Chemical Society.

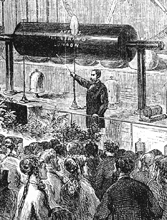

Pepper delivered his first lecture at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in 1847 and went on to take the role of analytical chemist and lecturer the year after. By the early 1850s he was its director. He introduced a series of evening classes covering educational and trade topics, and lectured by invitation at some of the most prestigious schools across England, including Eton, Harrow and Haileybury. Among the students at Eton was Quintin Hogg, who would go on to become a philanthropist and benefactor of the Royal Polytechnic Institution. Pepper also lectured in New York and Australia. Pepper became a highly regarded science performer and often went by the name "Professor Pepper". He regularly demonstrated a range of scientific and technological innovations with the intention of entertaining and educating the audience about how they worked. He used many of these to expose the trickery behind deceptive magic, and became famous for a new technique now known as "Pepper's ghost".

Liverpudlian engineer Henry Dircks is believed to have devised a method of projecting an actor onto a stage using a sheet of glass and a clever use of lighting, calling the technique "Dircksian Phantasmagoria". The actor would then have an ethereal, ghost like appearance while seemingly able to perform alongside other actors. Pepper saw the concept and replicated it on a larger scale, taking out a joint patent with Dircks. Pepper debuted his creation with a Christmas Eve production of the Charles Dickens play The Haunted Man in 1862 and Dircks signed over all financial rights to Pepper. Through this the effect became known as "Pepper's ghost", much to the frustration of Dircks, and though Pepper insisted that Dircks should have a share of the credit, the technique is still named after the man who popularized it. Some reports have suggested that, at the time, Pepper claimed to have developed the technique after reading the 1831 book Recreative Memoirs by famed showman Étienne - Gaspard Robert.

Pepper's demonstrations of "the ghost effect" were received with amazement by the general public while intriguing his fellow scientists. People returned to the theater repeatedly in an attempt to work out the method being used; famed physicist Michael Faraday eventually gave up and requested an explanation.

Pepper wrote eleven popular science books, starting with his first publications in the 1850s. 1861's The Playbook of Metals, built upon the work of Antonio Snider - Pellegrini and is regarded as an important step in the understanding of continental drift. The books became so successful, particularly The Boy's Playbook of Science, that they could be found in secondary schools throughout the United Kingdom, and some American reprints became prescribed school texts in Pennsylvania and Brooklyn.

Pepper was fascinated with electricity and light. In 1863 he illuminated Trafalgar Square and St. Paul's Cathedral to celebrate the marriage of Edward Albert, Prince of Wales, and Alexandra of Denmark. He achieved this using a variation of the arc lamp. On 21 December 1867 at a banquet of "noblemen and scientific gentlemen" Pepper arranged for a telegram to be sent between Arthur Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, and Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, who was in Washington at the time. The message took just under 10 minutes to arrive in the United States with a reply coming in after around 20 minutes. This transmission was hailed as a significant achievement for science.

With wife Mary Ann (born circa 1831), Pepper had a son (born circa 1856). Between 1874 and 1879 the family toured the United States and Canada before being invited to Australia. They arrived in Melbourne on 8 July 1879 and Pepper gave his first lecture just four days later. Interest in his demonstrations began to wane after a month, so he took his show to Sydney.

Pepper heard tales of Fred Fisher, a farmer in nearby Campbelltown who had mysteriously disappeared in 1826. A supposed sighting of Fisher's ghost sparked a legend that is still recounted today. Pepper incorporated the ghost into his shows, amazing his audiences for a while but, once again, the public desire for his shows tailed off after a month. For a time he tried his hand as playwright, producer and actor, putting on a romantic drama called Hermes and the Alchymist. The show was poorly received and lasted only a few weeks.

Over the next two years he took his show around Australia, visiting New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. After the tour he settled in Brisbane, Queensland, and worked as a public analyst. While there Pepper continued to deliver lectures and is believed to have been the first person to formally teach chemistry in the state.

The Summer of 1882 brought a drought to the southeast of Queensland with little rain and intense temperatures. Pepper believed that a scientific solution to the problem might be possible and decided to attempt a rainmaking experiment. He took out a front page advertisement in the 30 January 1882 issue of The Brisbane Courier to publicize the event, scheduled for 4 February 1882 at the Eagle Farm Racecourse. Further advertisements mentioned that there would be "several interesting Illustrations of Atmospheric Phenomena" and gave some details about the method that he planned to employ.

Pepper started his experiments in the weeks leading up to the public event. He gathered a range of materials including ten swivel guns, powerful rockets from HMS Cormorant, a land mine and a large quantity of gunpowder. The plan would be to create a bonfire that would billow smoke into the air, then an explosion in the clouds would contribute to a change in their electrical condition. He theorized that this would trigger the rainfall. Several helpers tried to launch a 20 foot steel kite into the air but had little success, finding it to be unwieldy. He reduced its size in time for the main show.

The Eagle Farm event was attended by nearly 700 people. Pepper's smaller kite only managed to fly a short distance into the sky and had to be abandoned. The swivel guns were then fired, attempting to create an explosion in the sky. However, due to an overfilling of powder in one of the guns, the only explosion of significance was the gun itself which was sent crashing into the empty grandstand. Another potentially dangerous incident was the launching of the rockets, one of which flew horizontally, narrowly missing the crowd.

The crowd were not impressed by the efforts of Pepper and his team, laughing and jeering at their failed attempts. Some members of the audience even joined in by trying to launch the kite themselves. The newspapers were also unkind with the Warwick Examiner and Times describing the event as being a "pseudo - scientific fiasco". Pepper felt very badly treated by fellow scientists and the general public and in a letter written to The Brisbane Courier dated 27 May 1882 he stated:

"My experiment in Queensland was received with such derision and insults that in the face of those hard steely railings I shall leave to others the honour and expense of trying to do good by gently persuading the clouds to drop fatness."

In the coming years other scientists attempted what Pepper called "cloud compelling". In another letter to The Brisbane Courier in April 1884 Pepper referred to one of them, saying that he hoped the scientist would "not be unappreciated or treated with the ribald and narrowminded jokes and judgments that were showered on my head."

Pepper returned to England in 1889 to enjoy his retirement. He died in Leytonstone on 25 March 1900. There is a memorial to Pepper at West Norwood Cemetery.