<Back to Index>

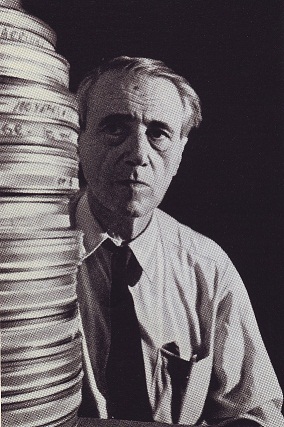

- Painter and Designer Hans Richter, 1888

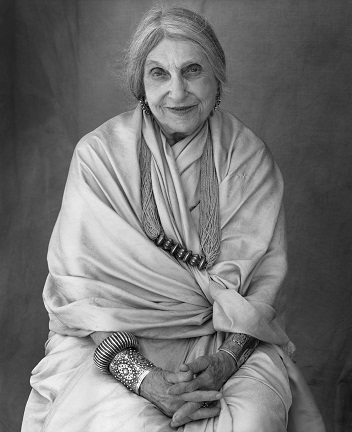

- Artist and Studio Potter Beatrice Wood, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

Hans Richter (April 6, 1888 – February 1, 1976) was a painter, graphic artist, avant gardist, film experimenter and producer. He was born in Berlin into a well - to - do family and died in Minusio, near Locarno, Switzerland.

Richter's first contacts with modern art were in 1912 through the "Blaue Reiter" and in 1913 through the "Erster Deutsche Herbstsalon" gallery "Der Sturm", in Berlin. In 1914 he was influenced by cubism. He contributed to the periodical Die Aktion in Berlin. His first exhibition was in Munich in 1916, and Die Aktion published as a special edition about him. In the same year he was wounded and discharged from the army and went to Zürich and joined the Dada movement.

Richter believed that the artist's duty was to be actively political, opposing war and supporting the revolution. His first abstract works were made in 1917. In 1918, he befriended Viking Eggeling, and the two experimented together with film. Richter was co-founder, in 1919, of the Association of Revolutionary Artists ("Artistes Radicaux") at Zürich. In the same year he created his first Prélude (an orchestration of a theme developed in eleven drawings). In 1920 he was a member of the November group in Berlin and contributed to the Dutch periodical De Stijl.

Throughout his career, he claimed that his 1921 film, Rhythmus 21, was the first abstract film ever created. This claim is not true: he was preceded by the Italian Futurists Bruno Corra and Arnaldo Ginna between 1911 and 1912 (as they report in the Futurist Manifesto of Cinema), as well as by fellow German artist Walter Ruttmann who produced Lichtspiel Opus 1 in 1920. Nevertheless, Richter's film Rhythmus 21 is considered an important early abstract film.

About Richter's woodcuts and drawings Michel Seuphor wrote: "Richter's black - and - whites together with those of Arp and Janco, are the most typical works of the Zürich period of Dada." From 1923 to 1926, Richter edited, together with Werner Gräff and Mies van der Rohe, the periodical G. Material zur elementaren Gestaltung. Richter wrote of his own attitude toward film:

- "I conceive of the film as a modern art form particularly interesting to the sense of sight. Painting has its own peculiar problems and specific sensations, and so has the film. But there are also problems in which the dividing line is obliterated, or where the two infringe upon each other. More especially, the cinema can fulfill certain promises made by the ancient arts, in the realization of which painting and film become close neighbors and work together."

Richter moved from Switzerland to the United States in 1940 and became an American citizen. He taught in the Institute of Film Techniques at the City College of New York.

While living in New York, Richter directed two feature films, Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947) and 8 x 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements (1957) in collaboration with Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, Paul Bowles, Fernand Léger, Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp and others, which was partially filmed on the lawn of his summer house in Southbury, Connecticut.

In 1957, he finished a film entitled Dadascope with original poems and prose spoken by their creators: Hans Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Raoul Hausmann, Richard Huelsenbeck and Kurt Schwitters.

After 1958, Richter spent parts of the year in Ascona and Connecticut and returned to painting.

Richter was also the author of a first - hand account of the Dada movement titled Dada: Art and Anti - Art, which also included his reflections on the emerging Neo - Dada artworks.

Beatrice Wood (March 3, 1893 – March 12, 1998) was an American artist and studio potter, who late in life was dubbed the "Mama of Dada," and served as a partial inspiration for the character of Rose DeWitt Bukater in James Cameron's 1997 film, Titanic. Beatrice Wood died nine days after her 105th birthday in Ojai, California.

Beatrice Wood was born in San Francisco, California, the daughter of wealthy socialites. Despite her parents' strong opposition, Wood insisted on pursuing a career in the arts. Eventually her parents agreed to let her study painting and because she was fluent in French, they sent her to Paris where she studied acting at the Comédie - Française and art at the prestigious Académie Julian.

The onset of World War I forced Wood to return to the United States. She continued acting with a French Repertory Company in New York City, performing over sixty roles in two years and spent a number of years thereafter performing on the stage.

During this time period, Wood was introduced to Marcel Duchamp, who in turn introduced her to her first great love interest, Henri - Pierre Roché, a man fourteen years her senior. She worked with Duchamp and Roché in the 1910s to create The Blind Man, a magazine that was one of the earliest manifestations of the Dada art movement in New York City.

Though she was involved with Roché, the two would often spend time with Duchamp, creating a love triangle. Biographies of Wood traditionally link Roché's novel (and the consequent film), Jules et Jim, with the relationship between Duchamp, Wood and himself. Other sources link their triangle to Roché's unfinished novel, Victor, and Jules et Jim with the triangle between Roché, Franz Hessel and Helen Hessel. Beatrice Wood commented on this topic in her 1985 autobiography, I Shock Myself:

Roché lived in Paris with his wife Denise, and had by now written Jules et Jim ... Because the story concerns two young men who are close friends and a woman who loves them both, people have wondered how much was based on Roché, Marcel and me. I cannot say what memories or episodes inspired Roché, but the characters bear only passing resemblance to those of us in real life!

Wood was next introduced to the art patrons, Walter and Louise Arensberg (who would become her lifelong friends). They held regular gatherings in which artists, writers and poets were invited for intellectual discussion. Besides herself, Duchamp, and Roché, the group included Man Ray and Francis Picabia. Beatrice Wood's relationship with them and others associated with the avant garde movement of the early 20th century, earned her the designation "Mama of Dada." Beatrice did not stay at the academy because it was too academic for her.

In her early forties, after a succession of failed artistic careers (most notably as an actress) and an annulled marriage, Beatrice moved back to Los Angeles, California.

It was at this time that she bought a pair of baroque plates with a luster glaze. She wanted to find a matching teapot to go along with it, but was unsuccessful. Deciding to make the teapot herself, she enrolled in a ceramic class at Hollywood High School. This hobby turned into a passion that would last over the next sixty years, as she developed a unique form of luster - glaze technique that proved successful.

In 1947, Beatrice felt that her career was established enough for her to build a home. She settled in Ojai, California, in 1948 to be near the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti and became a lifelong member of the Theosophical Society – Adyar, events which would greatly influence her artistic philosophies. She also taught and lived at the Happy Valley School, now known as Besant Hill School.

Ever the comedienne, when asked the secret to her incredible longevity, she would respond, "I owe it all to chocolate and young men."

In 1994, the Smithsonian Institution named Wood an "Esteemed American Artist".

Her home still rests on the campus of Besant Hill School and can be visited by appointment as it is still an active art gallery called The Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts.

The secondary market in Beatrice Wood art still thrives, and the largest collection can be viewed at BeatriceWoodArt.com, where major pieces such as Good Morning America, Madame Lola's Pleasure Palace, Chez Fifi, Waiting for Kennedy, and the last figurative work completed by Wood in 1997, Men With Their Wives, can be viewed.

- Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada: This documentary was released as a 16 mm film in Los Angeles, California on March 3, 1993, to coincide with Wood's 100th birthday.

- Titanic: Wood found a new audience when she was 104. She served as a partial inspiration for the 101 year old character of "Rose" in James Cameron's epic 1997 film, Titanic. In Titanic: James Cameron's Illustrated Screenplay, Cameron notes that Bill Paxton's wife loaned a copy of I Shock Myself to him. He realized upon reading it that "the first chapter describes almost literally the character I was already writing for 'Old Rose'... When I met her she was charming, creative and devastatingly funny... Of course, the film's Rose is only a refraction of Beatrice, combined with many fictional elements". According to her obituary in the Ojai Valley News, six days before her death, Wood awarded the Fifth Annual Beatrice Wood Film Award to Cameron.

- "First of all, I'd like to say here the fact that I'm not naturally a craftsman has made me work very hard."

- "And I have exposed myself to art so that my work has something beyond just the usual potter."

- "My life is full of mistakes. They're like pebbles that make a good road."

- "The second time I was there I met Marcel Duchamp, and we immediately fell for each other. Which doesn't mean a thing because I think anybody who met Marcel fell for him."

- "There's so much more to life than that, though I think that acting is fascinating because you can forget your own sorrow as you act and become somebody else."