<Back to Index>

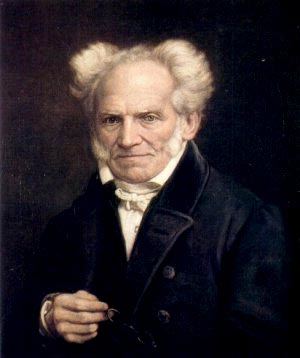

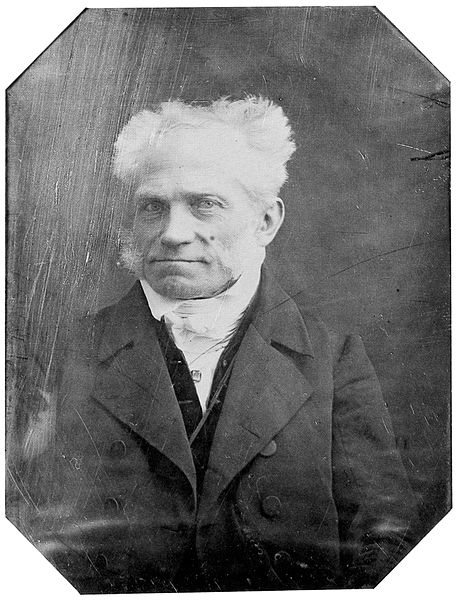

- Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, 1788

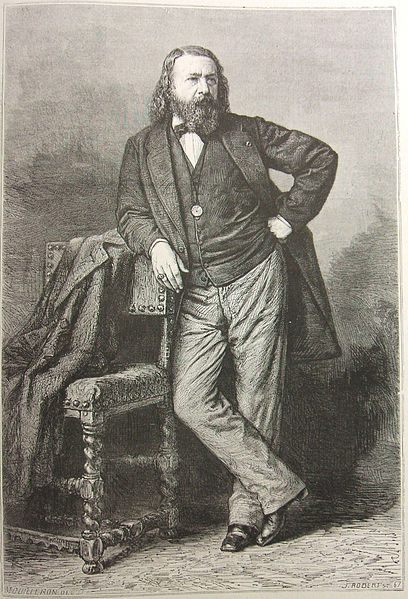

- Writer Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier, 1811

PAGE SPONSOR

Arthur Schopenhauer (22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher best known for his book, The World as Will and Representation; in it, he claimed that our world is driven by a continually dissatisfied will, continually seeking satisfaction. Influenced by Eastern thought, he maintained that the "truth was recognized by the sages of India"; consequently, his solutions to suffering were similar to those of Vedantic and Buddhist thinkers; his faith in "transcendental ideality" led him to accept atheism and learn from Christian philosophy.

At age 25, he published his doctoral dissertation, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, which examined the four distinct aspects of experience in the phenomenal world; consequently, he has been influential in the history of phenomenology. He has influenced a long list of thinkers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Richard Wagner, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Erwin Schrödinger, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Otto Rank, Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, Leo Tolstoy, Thomas Mann and Jorge Luis Borges.

Arthur Schopenhauer was born in the city of Danzig (Gdańsk), at Św. Ducha 47, the son of Johanna Schopenhauer (née Trosiener) and Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer, both descendants of wealthy German Patrician families. When the Kingdom of Prussia annexed the Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth city of Danzig in 1793, Schopenhauer's family moved to Hamburg. In 1805, Schopenhauer's father may have committed suicide. Shortly thereafter, Schopenhauer's mother Johanna moved to Weimar, then the center of German literature, to pursue her writing career. After one year, Schopenhauer left the family business in Hamburg to join her.

He became a student at the University of Göttingen in 1809. There he studied metaphysics and psychology under Gottlob Ernst Schulze, the author of Aenesidemus, who advised him to concentrate on Plato and Immanuel Kant. In Berlin, from 1811 to 1812, he had attended lectures by the prominent post - Kantian philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte and the theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher.

In 1814, Schopenhauer began his seminal work The World as Will and Representation (Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung). He finished it in 1818 and published it the following year. In Dresden in 1819, Schopenhauer fathered, with a servant, an illegitimate daughter who was born and died the same year. In 1820, Schopenhauer became a lecturer at the University of Berlin. He scheduled his lectures to coincide with those of the famous philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, whom Schopenhauer described as a "clumsy charlatan." However, only five students turned up to Schopenhauer's lectures, and he dropped out of academia. A late essay, On University Philosophy, expressed his resentment towards the work conducted in academies.

While in Berlin, Schopenhauer was named as a defendant in a lawsuit initiated by a woman named Caroline Marquet. She asked for damages, alleging that Schopenhauer had pushed her. According to Schopenhauer's court testimony, she deliberately annoyed him by raising her voice while standing right outside his door. Marquet alleged that the philosopher had assaulted and battered her after she refused to leave his doorway. Her companion testified that she saw Marquet prostrate outside his apartment. Because Marquet won the lawsuit, Schopenhauer made payments to her for the next twenty years. When she died, he wrote on a copy of her death certificate, Obit anus, abit onus ("The old woman dies, the burden is lifted").

In 1821, he fell in love with nineteen year old opera singer, Caroline Richter (called Medon), and had a relationship with her for several years. He discarded marriage plans, however, writing, "Marrying means to halve one's rights and double one's duties," and "Marrying means to grasp blindfolded into a sack hoping to find an eel among an assembly of snakes." When he was forty - three years old, seventeen year old Flora Weiss recorded rejecting him in her diary.

Schopenhauer had a notably strained relationship with his mother Johanna Schopenhauer. After his father's death, Arthur Schopenhauer endured two long years of drudgery as a merchant, in honor of his dead father. Afterward, his mother retired to Weimar, and Arthur Schopenhauer dedicated himself wholly to studies in the gymnasium of Gotha. After he left it in disgust after seeing one of the masters lampooned, he went to live with his mother. But by that time she had already opened her famous salon, and Arthur was not compatible with the vain, ceremonious ways of the salon. He was also disgusted by the ease with which Johanna Schopenhauer had forgotten his father's memory. Therefore, he gave university life a shot. There, he wrote his first book, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason. His mother informed him that the book was incomprehensible and it was unlikely that anyone would ever buy a copy. In a fit of temper Arthur Schopenhauer told her that his work would be read long after the rubbish she wrote would have been totally forgotten.

In 1831, a cholera epidemic broke out in Berlin and Schopenhauer left the city. Schopenhauer settled permanently in Frankfurt in 1833, where he remained for the next twenty - seven years, living alone except for a succession of pet poodles named Atman and Butz. The numerous notes that he made during these years, among others on aging, were published posthumously under the title Senilia.

Schopenhauer had a robust constitution, but in 1860 his health began to deteriorate. He died of heart failure on 21 September 1860, while sitting on his couch with his cat at home. He was 72.

A key focus of Schopenhauer was his investigation of individual motivation. Before Schopenhauer, Hegel had popularized the concept of Zeitgeist, the idea that society consisted of a collective consciousness which moved in a distinct direction, dictating the actions of its members. Schopenhauer, a reader of both Kant and Hegel, criticized their logical optimism and the belief that individual morality could be determined by society and reason. Schopenhauer believed that humans were motivated by only their own basic desires, or Wille zum Leben ("Will to Live"), which directed all of mankind.

For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world. He wrote "Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wants". In this sense, he adhered to the Fichtean principle of idealism: “the world is for a subject”. This idealism so presented, immediately commits it to an ethical attitude, unlike the purely epistemological concerns of Descartes and Berkeley. To Schopenhauer, the Will is a metaphysical existence which controls not only the actions of individual, intelligent agents, but ultimately all observable phenomena. He is credited with one of the most famous opening lines of philosophy: “The world is my representation”. Will, for Schopenhauer, is what Kant called the "thing - in - itself." Nietzsche was greatly influenced by this idea of Will, while developing it in a different direction.

For Schopenhauer, human desiring, "willing," and craving cause suffering or pain. A temporary way to escape this pain is through aesthetic contemplation (a method comparable to Zapffe's "Sublimation"). Aesthetic contemplation allows one to escape this pain — albeit temporarily — because it stops one perceiving the world as mere presentation. Instead, one no longer perceives the world as an object of perception (therefore as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds; time, space and causality) from which one is separated; rather one becomes one with that perception:"one can thus no longer separate the perceiver from the perception" (The World as Will and Representation, section 34). From this immersion with the world one no longer views oneself as an individual who suffers in the world due to one's individual will but, rather, becomes a "subject of cognition" to a perception that is "Pure, will - less, timeless" (section 34) where the essence, "ideas," of the world are shown. Art is the practical consequence of this brief aesthetic contemplation as it attempts to depict one's immersion with the world, thus tries to depict the essence / pure ideas of the world. Music, for Schopenhauer, was the purest form of art because it was the one that depicted the will itself without it appearing as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds, therefore as an individual object. According to Daniel Albright, "Schopenhauer thought that music was the only art that did not merely copy ideas, but actually embodied the will itself."

Schopenhauer's moral theory proposed that of three primary moral incentives, compassion, malice and egoism, compassion is the major motivator to moral expression. Malice and egoism are corrupt alternatives.

According to Schopenhauer, whenever we make a choice, "we assume as necessary that that decision was preceded by something from which it ensued, and which we call the ground or reason, or more accurately the motive, of the resultant action." Choices are not made freely. Our actions are necessary and determined because "every human being, even every animal, after the motive has appeared, must carry out the action which alone is in accordance with his inborn and immutable character." A definite action inevitably results when a particular motive influences a person's given, unchangeable character. The State, Schopenhauer claimed, punishes criminals in order to prevent future crimes. It does so by placing "beside every possible motive for committing a wrong a more powerful motive for leaving it undone, in the inescapable punishment. Accordingly, the criminal code is as complete a register as possible of counter motives to all criminal actions that can possibly be imagined...."

...the law and its fulfillment, namely punishment, are directed essentially to the future, not to the past. This distinguishes punishment from revenge, for revenge is motivated by what has happened, and hence by the past as such. All retaliation for wrong by inflicting a pain without any object for the future is revenge, and can have no other purpose than consolation for the suffering one has endured by the sight of the suffering one has caused in another. Such a thing is wickedness and cruelty, and cannot be ethically justified. ...the object of punishment... is deterrence from crime.... Object and purpose for the future distinguish punishment from revenge, and punishment has this object only when it is inflicted in fulfillment of a law. Only in this way does it proclaim itself to be inevitable and infallible for every future case; and thus it obtains for the law the power to deter....

Should capital punishment be legal? "For safeguarding the lives of citizens," he asserted, "capital punishment is therefore absolutely necessary." "The murderer," wrote Schopenhauer, "who is condemned to death according to the law must, it is true, be now used as a mere means, and with complete right. For public security, which is the principal object of the State, is disturbed by him; indeed it is abolished if the law remains unfulfilled. The murderer, his life, his person, must be the means of fulfilling the law, and thus of reestablishing public security." Schopenhauer disagreed with those who would abolish capital punishment. "Those who would like to abolish it should be given the answer: 'First remove murder from the world, and then capital punishment ought to follow.' "

People, according to Schopenhauer, cannot be improved. They can only be influenced by strong motives that overpower criminal motives. Schopenhauer declared that "real moral reform is not at all possible, but only determent from the deed...."

He claimed that this doctrine was not original with him. Previously, it appeared in the writings of Plato, Seneca, Hobbes, Pufendorf, and Anselm Feuerbach. Schopenhauer declared that their teaching was corrupted by subsequent errors and therefore was in need of clarification.

Schopenhauer was perhaps even more influential in his treatment of man's psychology than he was in the realm of philosophy.

Philosophers have not traditionally been impressed by the tribulations of sex, but Schopenhauer addressed it and related concepts forthrightly:

...one ought rather to be surprised that a thing [sex] which plays throughout so important a part in human life has hitherto practically been disregarded by philosophers altogether, and lies before us as raw and untreated material.

He gave a name to a force within man which he felt had invariably precedence over reason: the Will to Live or Will to Life (Wille zum Leben), defined as an inherent drive within human beings, and indeed all creatures, to stay alive and to reproduce.

Schopenhauer refused to conceive of love as either trifling or accidental, but rather understood it to be an immensely powerful force lying unseen within man's psyche and dramatically shaping the world:

The ultimate aim of all love affairs ... is more important than all other aims in man's life; and therefore it is quite worthy of the profound seriousness with which everyone pursues it.

What is decided by it is nothing less than the composition of the next generation ...

These ideas foreshadowed the discovery of evolution, Freud's concepts of the libido and the unconscious mind, and evolutionary psychology in general.

Schopenhauer's politics were, for the most part, an echo of his system of ethics (the latter being expressed in Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik, available in English as two separate books, On the Basis of Morality and On the Freedom of the Will). Ethics also occupies about one quarter of his central work, The World as Will and Representation.

In occasional political comments in his Parerga and Paralipomena and Manuscript Remains, Schopenhauer described himself as a proponent of limited government. What was essential, he thought, was that the state should "leave each man free to work out his own salvation", and so long as government was thus limited, he would "prefer to be ruled by a lion than one of [his] fellow rats" — i.e., by a monarch, rather than a democrat. Schopenhauer shared the view of Thomas Hobbes on the necessity of the state, and of state action, to check the destructive tendencies innate to our species. He also defended the independence of the legislative, judicial and executive branches of power, and a monarch as an impartial element able to practice justice (in a practical and everyday sense, not a cosmological one). He declared monarchy as "that which is natural to man" for "intelligence has always under a monarchical government a much better chance against its irreconcilable and ever - present foe, stupidity" and disparaged republicanism as "unnatural as it is unfavorable to the higher intellectual life and the arts and sciences."

Schopenhauer, by his own admission, did not give much thought to politics, and several times he writes proudly of how little attention he had paid "to political affairs of [his] day". In a life that spanned several revolutions in French and German government, and a few continent shaking wars, he did indeed maintain his aloof position of "minding not the times but the eternities". He wrote many disparaging remarks about Germany and the Germans. A typical example is, "For a German it is even good to have somewhat lengthy words in his mouth, for he thinks slowly, and they give him time to reflect."

Schopenhauer attributed civilizational primacy to the northern "white races" due to their sensitivity and creativity (except for the ancient Egyptians and Hindus whom he saw as equal):

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in color than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmans, the Incas and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate. This they had to do in order to make up for the parsimony of nature and out of it all came their high civilization.

Despite this, he was adamantly against differing treatment of races, was fervently anti - slavery, and supported the abolitionist movement in the United States. He describes the treatment of "[our] innocent black brothers whom force and injustice have delivered into [the slave master's] devilish clutches" as "belonging to the blackest pages of mankind's criminal record".

Schopenhauer additionally maintained a marked metaphysical and political anti - Judaism. Schopenhauer argued that Christianity constituted a revolt against the materialistic basis of Judaism, exhibiting an Indian - influenced ethics reflecting the Aryan - Vedic theme of spiritual "self conquest." This he saw as opposed to what he held to be the ignorant drive toward earthly utopianism and superficiality of a worldly Jewish spirit:

While all other religions endeavor to explain to the people by symbols the metaphysical significance of life, the religion of the Jews is entirely immanent and furnishes nothing but a mere war - cry in the struggle with other nations.

In Schopenhauer's 1851 essay "Of Women" ("Über die Weiber"), he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico - Christian stupidity" on female affairs. He claimed that "woman is by nature meant to obey", and opposed Schiller's poem in honor of women, "Würde der Frauen" ("Dignity of Women"). The essay does give two compliments, however: that "women are decidedly more sober in their judgment than [men] are" and are more sympathetic to the suffering of others.

Schopenhauer's controversial writings have influenced many, from Friedrich Nietzsche to nineteenth century feminists. Schopenhauer's biological analysis of the difference between the sexes, and their separate roles in the struggle for survival and reproduction, anticipates some of the claims that were later ventured by sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists.

After the elderly Schopenhauer sat for a sculpture portrait by Elisabet Ney, he told Richard Wagner's friend Malwida von Meysenbug, "I have not yet spoken my last word about women. I believe that if a woman succeeds in withdrawing from the mass, or rather raising herself above the mass, she grows ceaselessly and more than a man."

Schopenhauer believed that personality and intellect were inherited. He quotes Horace's saying, "From the brave and good are the brave descended" (Odes, iv, 4, 29) and Shakespeare's line from Cymbeline, "Cowards father cowards, and base things sire base" (IV, 2) to reinforce his hereditarian argument. Mechanistically, Schopenhauer believed that a person inherits his level of intellect through his mother, and personal character through one's father. This belief in hereditability of traits informed Schopenhauer's view of love – placing it at the highest level of importance. For Schopenhauer the “final aim of all love intrigues, be they comic or tragic, is really of more importance than all other ends in human life. What it all turns upon is nothing less than the composition of the next generation.... It is not the weal or woe of any one individual, but that of the human race to come, which is here at stake.” This view of the importance for the species of whom we choose to love was reflected in his views on eugenics or good breeding. Here Schopenhauer wrote:

With our knowledge of the complete unalterability both of character and of mental faculties, we are led to the view that a real and thorough improvement of the human race might be reached not so much from outside as from within, not so much by theory and instruction as rather by the path of generation. Plato had something of the kind in mind when, in the fifth book of his Republic, he explained his plan for increasing and improving his warrior caste. If we could castrate all scoundrels and stick all stupid geese in a convent, and give men of noble character a whole harem, and procure men, and indeed thorough men, for all girls of intellect and understanding, then a generation would soon arise which would produce a better age than that of Pericles.

In another context, Schopenhauer reiterated his antidemocratic - eugenic thesis: "If you want Utopian plans, I would say: the only solution to the problem is the despotism of the wise and noble members of a genuine aristocracy, a genuine nobility, achieved by mating the most magnanimous men with the cleverest and most gifted women. This proposal constitutes my Utopia and my Platonic Republic". Analysts (e.g., Keith Ansell - Pearson) have suggested that Schopenhauer's advocacy of anti - egalitarianism and eugenics influenced the neo - aristocratic philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, who initially considered Schopenhauer his mentor.

As a consequence of his monistic philosophy, Schopenhauer was very concerned about the welfare of animals. For him, all individual animals, including humans, are essentially the same, being phenomenal manifestations of the one underlying Will. The word "will" designated, for him, force, power, impulse, energy and desire; it is the closest word we have that can signify both the real essence of all external things and also our own direct, inner experience. Since everything is basically Will, then humans and animals are fundamentally the same and can recognize themselves in each other. For this reason, he claimed that a good person would have sympathy for animals, who are our fellow sufferers.

Compassion for animals is intimately associated with goodness of character, and it may be confidently asserted that he who is cruel to living creatures cannot be a good man.

Nothing leads more definitely to a recognition of the identity of the essential nature in animal and human phenomena than a study of zoology and anatomy.

The assumption that animals are without rights and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality.

In 1841, he praised the establishment, in London, of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and also the Animals' Friends Society in Philadelphia. Schopenhauer even went so far as to protest against the use of the pronoun "it" in reference to animals because it led to the treatment of them as though they were inanimate things. To reinforce his points, Schopenhauer referred to anecdotal reports of the look in the eyes of a monkey who had been shot and also the grief of a baby elephant whose mother had been killed by a hunter.

He was very attached to his succession of pet poodles. Schopenhauer criticized Spinoza's belief that animals are to be used as a mere means for the satisfaction of humans.

Schopenhauer was also one of the first philosophers since the days of Greek philosophy to address the subject of male homosexuality. In the third, expanded edition of The World as Will and Representation (1856), Schopenhauer added an appendix to his chapter on the "Metaphysics of Sexual Love". He also wrote that homosexuality did have the benefit of preventing ill - begotten children. Concerning this, he stated, "... the vice we are considering appears to work directly against the aims and ends of nature, and that in a matter that is all important and of the greatest concern to her, it must in fact serve these very aims, although only indirectly, as a means for preventing greater evils." Shrewdly anticipating the interpretive distortion, on the part of the popular mind, of his attempted scientific explanation of pederasty as personal advocacy (when he had otherwise described the act, in terms of spiritual ethics, as an "objectionable aberration"), Schopenhauer sarcastically concludes the appendix with the statement that "by expounding these paradoxical ideas, I wanted to grant to the professors of philosophy a small favor, for they are very disconcerted by the ever increasing publicization of my philosophy which they so carefully concealed. I have done so by giving them the opportunity of slandering me by saying that I defend and commend pederasty."

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation of the Upanishads which had been translated by French writer Anquetil du Perron from the Persian translation of Prince Dara Shikoh entitled Sirre - Akbar ("The Great Secret"). He was so impressed by their philosophy that he called them "the production of the highest human wisdom," and considered them to contain superhuman conceptions. The Upanishads was a great source of inspiration to Schopenhauer, and writing about them he said:

It is the most satisfying and elevating reading (with the exception of the original text) which is possible in the world; it has been the solace of my life and will be the solace of my death.

It is well known that the book Oupnekhat (Upanishad) always lay open on his table, and he invariably studied it before sleeping at night. He called the opening up of Sanskrit literature "the greatest gift of our century", and predicted that the philosophy and knowledge of the Upanishads would become the cherished faith of the West.

Schopenhauer was first introduced to the 1802 Latin Upanishad translation through Friedrich Majer. They met during the winter of 1813 - 1814 in Weimar at the home of Schopenhauer’s mother according to the biographer Sanfranski. Majer was a follower of Herder, and an early Indologist. Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of the Indic texts, however, until the summer of 1814. Sansfranski maintains that between 1815 and 1817, Schopenhauer had another important cross - pollination with Indian Thought in Dresden. This was through his neighbor of two years, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause. Krause was then a minor and rather unorthodox philosopher who attempted to mix his own ideas with that of ancient Indian wisdom. Krause had also mastered Sanskrit, unlike Schopenhauer, and the two developed a professional relationship. It was from Krause that Schopenhauer learned meditation and received the closest thing to expert advice concerning Indian thought.

Most noticeable, in the case of Schopenhauer’s work, was the significance of the Chandogya Upanishad, whose Mahavakya, Tat Tvam Asi is mentioned throughout The World as Will and Representation.

Schopenhauer noted a correspondence between his doctrines and the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. Similarities centered on the principles that life involves suffering, that suffering is caused by desire (tanha), and that the extinction of desire leads to liberation. Thus three of the four "truths of the Buddha" correspond to Schopenhauer's doctrine of the will. In Buddhism, however, while greed and lust are always unskillful, desire is ethically variable - it can be skillful, unskillful or neutral.

For Schopenhauer, Will had ontological primacy over the intellect; in other words, desire is understood to be prior to thought. Schopenhauer felt this was similar to notions of purushartha or goals of life in Vedanta Hinduism.

In Schopenhauer's philosophy, denial of the will is attained by either:

- personal experience of an extremely great suffering that leads to loss of the will to live; or

- knowledge of the essential nature of life in the world through observation of the suffering of other people.

However, Buddhist nirvana is not equivalent to the condition that Schopenhauer described as denial of the will. Nirvana is not the extinguishing of the person as some Western scholars have thought, but only the "extinguishing" (the literal meaning of nirvana) of the flames of greed, hatred and delusion that assail a person's character. Occult historian Joscelyn Godwin stated, "It was Buddhism that inspired the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, and, through him, attracted Richard Wagner. This Orientalism reflected the struggle of the German Romantics, in the words of Leon Poliakov, to free themselves from Judeo - Christian fetters". In contradistinction to Godwin's claim that Buddhism inspired Schopenhauer, the philosopher himself made the following statement in his discussion of religions:

If I wished to take the results of my philosophy as the standard of truth, I should have to concede to Buddhism pre - eminence over the others. In any case, it must be a pleasure to me to see my doctrine in such close agreement with a religion that the majority of men on earth hold as their own, for this numbers far more followers than any other. And this agreement must be yet the more pleasing to me, inasmuch as in my philosophizing I have certainly not been under its influence [emphasis added]. For up till 1818, when my work appeared, there was to be found in Europe only a very few accounts of Buddhism.

Buddhist philosopher Nishitani Keiji, however, sought to distance Buddhism from Schopenhauer. While Schopenhauer's philosophy may sound rather mystical in such a summary, his methodology was resolutely empirical, rather than speculative or transcendental:

Philosophy ... is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions.

Also note:

This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.

The argument that Buddhism affected Schopenhauer’s philosophy more than any other Dharmic faith loses more credence when viewed in light of the fact that Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of Buddhism until after the publication of The World as Will and Representation in 1818. Scholars have started to revise earlier views about Schopenhauer's discovery of Buddhism. Proof of early interest and influence appears in Schopenhauer's 1815 / 16 notes (transcribed and translated by Urs App) about Buddhism. They are included in a recent case study that traces Schopenhauer's interest in Buddhism and documents its influence.

Schopenhauer said he was influenced by the Upanishads, Immanuel Kant and Plato. References to Eastern philosophy and religion appear frequently in Schopenhauer's writing. As noted above, he appreciated the teachings of the Buddha and even called himself a "Buddhist". He said that his philosophy could not have been conceived before these teachings were available.

Concerning the Upanishads and Vedas, he writes in The World as Will and Representation:

If the reader has also received the benefit of the Vedas, the access to which by means of the Upanishads is in my eyes the greatest privilege which this still young century (1818) may claim before all previous centuries, if then the reader, I say, has received his initiation in primeval Indian wisdom, and received it with an open heart, he will be prepared in the very best way for hearing what I have to tell him. It will not sound to him strange, as to many others, much less disagreeable; for I might, if it did not sound conceited, contend that every one of the detached statements which constitute the Upanishads, may be deduced as a necessary result from the fundamental thoughts which I have to enunciate, though those deductions themselves are by no means to be found there.

He summarized the influence of the Upanishads thus: "It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death!"

Among Schopenhauer's other influences were: Shakespeare, Jean - Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Matthias Claudius, George Berkeley, David Hume, and René Descartes.

Schopenhauer accepted Kant's double - aspect of the universe — the phenomenal (world of experience) and the noumenal (the true world, independent of experience). Some commentators suggest that Schopenhauer claimed that the noumenon, or thing - in - itself, was the basis for Schopenhauer's concept of the will. Other commentators suggest that Schopenhauer considered will to be only a subset of the "thing - in - itself" class, namely that which we can most directly experience.

Schopenhauer's identification of the Kantian noumenon (i.e., the actually existing entity) with what he termed "will" deserves some explanation. The noumenon was what Kant called the Ding an Sich, the "Thing in Itself", the reality that is the foundation of our sensory and mental representations of an external world. In Kantian terms, those sensory and mental representations are mere phenomena. Schopenhauer departed from Kant in his description of the relationship between the phenomenon and the noumenon. According to Kant, things - in - themselves ground the phenomenal representations in our minds; Schopenhauer, on the other hand, believed phenomena and noumena to be two different sides of the same coin. Noumena do not cause phenomena, but rather phenomena are simply the way by which our minds perceive the noumena, according to the Principle of Sufficient Reason. This is explained more fully in Schopenhauer's doctoral thesis, On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason.

Schopenhauer's second major departure from Kant's epistemology concerns the body. Kant's philosophy was formulated as a response to the radical philosophical skepticism of David Hume, who claimed that causality could not be observed empirically. Schopenhauer begins by arguing that Kant's demarcation between external objects, knowable only as phenomena, and the Thing in Itself of noumenon, contains a significant omission. There is, in fact, one physical object we know more intimately than we know any object of sense perception: our own body.

We know our human bodies have boundaries and occupy space, the same way other objects known only through our named senses do. Though we seldom think of our body as a physical object, we know even before reflection that it shares some of an object's properties. We understand that a watermelon cannot successfully occupy the same space as an oncoming truck; we know that if we tried to repeat the experiment with our own body, we would obtain similar results – we know this even if we do not understand the physics involved.

We know that our consciousness inhabits a physical body, similar to other physical objects only known as phenomena. Yet our consciousness is not commensurate with our body. Most of us possess the power of voluntary motion. We usually are not aware of the breathing of our lungs or the beating of our heart unless somehow our attention is called to them. Our ability to control either is limited. Our kidneys command our attention on their schedule rather than one we choose. Few of us have any idea what our liver is doing right now, though this organ is as needful as lungs, heart, or kidneys. The conscious mind is the servant, not the master, of these and other organs; these organs have an agenda which the conscious mind did not choose, and over which it has limited power.

When Schopenhauer identifies the noumenon with the desires, needs, and impulses in us that we name "will," what he is saying is that we participate in the reality of an otherwise unachievable world outside the mind through will. We cannot prove that our mental picture of an outside world corresponds with a reality by reasoning; through will, we know – without thinking – that the world can stimulate us. We suffer fear, or desire: these states arise involuntarily; they arise prior to reflection; they arise even when the conscious mind would prefer to hold them at bay. The rational mind is, for Schopenhauer, a leaf borne along in a stream of pre-reflective and largely unconscious emotion. That stream is will, and through will, if not through logic, we can participate in the underlying reality beyond mere phenomena. It is for this reason that Schopenhauer identifies the noumenon with what we call our will.

In his criticism of Kant, Schopenhauer claimed that sensation and understanding are separate and distinct abilities. Yet, for Kant, an object is known through each of them. Kant wrote: "... [T]here are two stems of human knowledge ... namely, sensibility and understanding, objects being given by the former [sensibility] and thought by the latter [understanding]." Schopenhauer disagreed. He asserted that mere sense impressions, not objects, are given by sensibility. According to Schopenhauer, objects are intuitively perceived by understanding and are discursively thought by reason (Kant had claimed that (1) the understanding thinks objects through concepts and that (2) reason seeks the unconditioned or ultimate answer to "why?"). Schopenhauer said that Kant's mistake regarding perception resulted in all of the obscurity and difficult confusion that is exhibited in the Transcendental Analytic section of his critique.

Lastly, Schopenhauer departed from Kant in how he interpreted the Platonic ideas. In The World as Will and Representation Schopenhauer explicitly stated:

...Kant used the word [Idea] wrongly as well as illegitimately, although Plato had already taken possession of it, and used it most appropriately.

Instead Schopenhauer relied upon the Neoplatonist interpretation of the biographer Diogenes Laërtius from Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. In reference to Plato’s Ideas, Schopenhauer quotes Laërtius verbatim in an explanatory footnote.

Diogenes Laërtius (III, 12) Plato ideas in natura velut exemplaria dixit subsistere; cetera his esse similia, ad istarum similitudinem consistencia. (Plato teaches that the Ideas exist in nature, so to speak, as patterns or prototypes, and that the remainder of things only resemble them, and exist as their copies.)

Schopenhauer expressed his dislike for the philosophy of his contemporary Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel many times in his published works. The following quotations are typical:

If I were to say that the so-called philosophy of this fellow Hegel is a colossal piece of mystification which will yet provide posterity with an inexhaustible theme for laughter at our times, that it is a pseudo - philosophy paralyzing all mental powers, stifling all real thinking, and, by the most outrageous misuse of language, putting in its place the hollowest, most senseless, thoughtless, and, as is confirmed by its success, most stupefying verbiage, I should be quite right.

Further, if I were to say that this summus philosophus [...] scribbled nonsense quite unlike any mortal before him, so that whoever could read his most eulogized work, the so-called Phenomenology of the Mind, without feeling as if he were in a madhouse, would qualify as an inmate for Bedlam, I should be no less right.

At first Fichte and Schelling shine as the heroes of this epoch; to be followed by the man who is quite unworthy even of them, and greatly their inferior in point of talent --- I mean the stupid and clumsy charlatan Hegel.

In his Foreword to the first edition of his work Die beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik, Schopenhauer suggested that he had shown Hegel to have fallen prey to the Post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

Schopenhauer suggested that Hegel's works were filled with "castles of abstraction," and that Hegel used deliberately impressive but ultimately vacuous verbiage. He also thought that his glorification of church and state were designed for personal advantage and had little to do with the search for philosophical truth. For instance, the Right Hegelians interpreted Hegel as viewing the Prussian state of his day as perfect and the goal of all history up until then.

Schopenhauer has had a massive influence upon later thinkers, though more so in the arts (especially literature and music) and psychology than in philosophy. His popularity peaked in the early twentieth century, especially during the Modernist era, and waned somewhat thereafter. Nevertheless, a number of recent publications have reinterpreted and modernized the study of Schopenhauer. His theory is also being explored by some modern philosophers as a precursor to evolutionary theory and modern evolutionary psychology.

Richard Wagner, writing in his autobiography, remembered his first impression that Schopenhauer left on him (when he read World as will and representation):

Schopenhauer’s book was never completely out of my mind, and by the following summer I had studied it from cover to cover four times. It had a radical influence on my whole life.

Wagner also commented that "serious mood, which was trying to find ecstatic expression" created by Schopenhauer inspired the conception of Tristan und Isolde.

Friedrich Nietzsche owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading The World as Will and Representation and admitted that he was one of the few philosophers that he respected, dedicating to him his essay Schopenhauer als Erzieher one of his Untimely Meditations.

Jorge Luis Borges remarked that the reason he had never attempted to write a systematic account of his world view, despite his penchant for philosophy and metaphysics in particular, was because Schopenhauer had already written it for him.

As a teenager, Ludwig Wittgenstein was strongly influenced by Schopenhauer's epistemological idealism. However, after his study of the philosophy of mathematics, he abandoned epistemological idealism for Gottlob Frege's conceptual realism.

The philosopher Gilbert Ryle read Schopenhauer's works as a student, but later largely forgot them. He unwittingly recycled ideas from Schopenhauer in his The Concept of Mind.

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier (30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, art critic and literary critic.

While Gautier was an ardent defender of Romanticism, his work is difficult to classify and remains a point of reference for many subsequent literary traditions such as Parnassianism, Symbolism, Decadence and Modernism. He was widely esteemed by writers as diverse as Balzac, Baudelaire, the Goncourt brothers, Flaubert, Proust and Oscar Wilde.

Gautier was born on 30 August 1811 in Tarbes, capital of Hautes - Pyrénées département in southwestern France. His father, Pierre Gautier, was a fairly cultured minor government official and his mother was Antoinette - Adelaïde Concarde. The family moved to Paris in 1814, taking up residence in the ancient Marais district.

Gautier's education commenced at the prestigious Collège Louis - le - Grand in Paris (fellow alumni include Voltaire and Charles Baudelaire), which he attended for three months before being brought home due to illness. Although he completed the remainder of his education at Collège Charlemagne (alumni include Charles Augustin Sainte - Beuve), Gautier's most significant instruction came from his father, who prompted him to become a Latin scholar by age 18.

While at school, Gautier befriended Gérard de Nerval and the two became lifelong friends. It is through Nerval that Gautier was introduced to Victor Hugo, by then already a well known, established leading dramatist and author of Hernani. Hugo became a major influence on Gautier and is credited for giving him, an aspiring painter at the time, an appetite for literature. It was at the legendary premier of Hernani that Gautier is remembered for wearing his anachronistic red doublet.

In the aftermath of the 1830 Revolution, Gautier's family experienced hardship and was forced to move to the outskirts of Paris. Deciding to experiment with his own independence and freedom, Gautier chose to stay with friends in the Doyenné district of Paris, living a rather pleasant bohemian life.

Towards the end of 1830, Gautier began to frequent meetings of Le Petit Cénacle [The Little Upper Room], a group of artists who met in the studio of Jehan Du Seigneur. The group was a more irresponsible version of Hugo's Cénacle. The group counted among its members the artists Gérard de Nerval, Alexandre Dumas, père, Petrus Borel, Alphonse Brot, Joseph Bouchardy and Philothée O’Neddy (real name Théophile Dondey). Le Petit Cénacle soon gained a reputation for extravagance and eccentricity, but also for being a unique refuge from society.

Gautier began writing poetry as early as 1826 but the majority of his life was spent as a contributor to various journals, mainly La Presse, which also gave him the opportunity for foreign travel and for meeting many influential contacts in high society and in the world of the arts. Throughout his life, Gautier was well traveled, taking trips to Spain, Italy, Russia, Egypt and Algeria. Gautier's many travels inspired many of his writings including Voyage en Espagne (1843), Trésors d’Art de la Russie (1858) and Voyage en Russie (1867). Gautier's travel literature is considered by many as being some of the best from the nineteenth century, often written in a more personal style, it provides a window into Gautier's own tastes in art and culture.

Gautier was a celebrated abandonnée [one who yields or abandons himself to something] of the Romantic Ballet, writing several scenarios, the most famous of which is Giselle, whose first interpreter, the ballerina Carlotta Grisi, was the great love of his life. She could not return his affection, so he married her sister Ernestina, a singer.

Absorbed by the 1848 Revolution, Gautier wrote almost one hundred articles, equivalent to four large books, within nine months in 1848. Gautier experienced a prominent time in his life when the original romantics such as Hugo, François - René de Chateaubriand, Alphonse de Lamartine, Alfred de Vigny and Alfred de Musset were no longer actively participating in the literary world. His prestige was confirmed by his role as director of Revue de Paris from 1851 - 1856. During this time, Gautier left La Presse and became a journalist for Le Moniteur universel, finding the burden of regular journalism quite unbearable and "humiliating." Nevertheless, Gautier acquired the editorship of the influential review L’Artiste in 1856. It is through this review that Gautier publicized Art for art's sake doctrines through many editorials.

The 1860s were years of assured literary fame for Gautier. Although he was rejected by the French Academy three times (1867, 1868, 1869), Charles - Augustin Sainte - Beuve, the most influential critic of the day, set the seal of approval on the poet by devoting no less than three major articles in 1863 to reviews of Gautier's entire published works. In 1865, Gautier was admitted into the prestigious salon of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, cousin of Napoleon III and niece to Bonaparte. The Princess offered Gautier a sinecure as her librarian in 1868, a position that gave him access to the court of Napoleon III.

Elected in 1862 as chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux - Arts, he was surrounded by a committee of important painters: Eugène Delacroix, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Édouard Manet, Albert - Ernest Carrier - Belleuse and Gustave Doré.

During the Franco - Prussian War, Gautier made his way back to Paris upon hearing of the Prussian advance on the capital. He remained with his family throughout the invasion and the aftermath of the Commune, eventually dying on 23 October 1872 due to a long standing cardiac disease. Gautier was sixty - one years old. He is interred at the Cimetière de Montmartre in Paris. He was made a Chevalier de la Legion d'honneur in 1842. He was promoted to an Officier de la Legion d'honneur in 1858.

Early in his life, Gautier befriended Gérard de Nerval, who influenced him greatly in his earlier poetry and also through whom he was introduced to Victor Hugo. He shared in Hugo's dissatisfaction with the theatrical outputs of the time and the use of the word "tragedy." Gautier admired Honoré de Balzac for his contributions to the development of French literature.

As Gautier was influenced greatly by his friends as well, paying tribute to them in his writings. In fact, he dedicated his collection of Dernières Poésies to his many friends, including Hérbert, Madame de la Grangerie, Maxime Du Camp and Princess Mathilde Bonaparte.

Gautier spent the majority of his career as a journalist at La Presse and later on at Le Moniteur universel. He saw journalistic criticism as a means to a middle class standard of living. The income was adequate and he had ample opportunities to travel. Gautier began contributing art criticisms to obscure journals as early as 1831. It was not until 1836 that he experienced a jump in his career when he was hired by Émile de Girardin as an art and theater columnist for La Presse. During his time at La Presse, however, Gautier also contributed nearly 70 articles to Le Figaro. After leaving La Presse to work for Le Moniteur universel, the official newspaper of the Second Empire, Gautier wrote both to inform the public and to influence its choices. His role at the newspaper was equivalent to the modern book or theater reviewer.

Gautier's literary criticism was more reflective in nature, criticism which had no immediate commercial function but simply appealed to his own taste and interests. Later in his life, he wrote extensive monographs on such giants as Gérard de Nerval, Balzac and Baudelaire, who were also his friends.

Gautier, who started off as a painter, contributed much to the world of art criticism. Instead of taking on the classical criticism of art that involved knowledge of color, composition and line, Gautier was strongly influenced by Denis Diderot's idea that the critic should have the ability to describe the art so as the reader can "see" the art through his description. Many other critics of the generation of 1830 took on this theory of the transposition of art – the belief that one can express one art medium in terms of another. Although today Gautier is less well known as an art critic than his great contemporary, Baudelaire, he was more highly regarded by the painters of his time. In 1862 he was elected chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux - Arts (National Society of Fine Arts) with a board which included Eugène Delacroix, Édouard Manet, Gustave Doré and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

Gautier's literary criticism was more reflective in nature; his literary analysis was free from the pressure of his art and theater columns and therefore, he was able to express his ideas without restriction. He made a clear distinction between prose and poetry, stating that prose should never be considered the equal of poetry. The bulk of Gautier's criticism, however, was journalistic. He raised the level of journalistic criticism of his day.

The majority of Gautier's career was spent writing a weekly column of theatrical criticism. Because Gautier wrote so frequently on plays, he began to consider the nature of the plays and developed the criteria by which they should be judged. He suggested that the normal five acts of a play could be reduced to three: an exposition, a complication and a dénouement. Having abandoned the idea that tragedy is the superior genre, Gautier was willing to accept comedy as the equal of tragedy. Taking it a step further, he suggested that the nature of the theatrical effect should be in favor of creating fantasy rather than portraying reality because realistic theater was undesirable.

From a 21st century standpoint Gautier's writings about dance are the most significant of his writings. The American writer Edwin Denby, widely considered the most significant writer about dance in the 20th century, called him "by common consent the greatest of ballet critics." Gautier, Denby says, "seems to report wholly from the point of view of a civilized entertainment seeker." He founds his judgments not on theoretical principles but in sensuous perception, starting from the physical form and vital energy of the individual dancer. This emphasis has remained a tacit touchstone of dance writing ever since. Through his authorship of the scenario of the ballet Giselle, one of the foundation works of the dance repertoire, his influence remains as great among choreographers and dancers as among critics and balletomanes [devotees of ballet].

In 2011, Pacific Northwest Ballet presented a reconstruction of the work as close to its narrative and choreographic sources as possible, based on archival materials dating back to 1842, the year after its premiere.

In many of Gautier's works, the subject is less important than the pleasure of telling the story. He favored a provocative yet refined style. The list below links each year of publication with its corresponding "[year] in poetry" article, for poetry, or "[year] in literature" article for other works):

- Poésies, published in 1830, is a collection of 42 poems that Gautier composed at the age of 18. However, as the publication took place during the July Revolution, no copies were sold and it was eventually withdrawn. In 1832, the collection was reissued with 20 additional poems under the name Albertus. Another edition in 1845 included revisions of some of the poems. The poems are written in a wide variety of verse forms and show that Gautier attempts to imitate other, more established Romantic poets such as Sainte - Beuve, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Hugo, before Gautier eventually found his own way by becoming a critic of Romantic excesses.

- Albertus, written in 1831 and published in 1832, is a long narrative poem of 122 stanzas, each consisting of 12 lines of alexandrine (12 - syllable) verse, except for the last line of each stanza, which is octosyllabic. Albertus is a parody of Romantic literature, especially of tales of the macabre and the supernatural. The poem tells a story of an ugly witch who magically transforms at midnight into an alluring young woman. Albertus, the hero, falls deeply in love and agrees to sell his soul.

- Les Jeunes - France ("The Jeunes - France: Tales Told with Tongue in Cheek"), published in 1833, was a satire of Romanticism. In 1831, the newspaper Le Figaro featured a number of works by the young generation of Romantic artists and published them in the Jeunes - France.

- La Comédie de la Mort, published in 1838, is a period piece much like Albertus. In this work, Gautier focuses on the theme of death, which for Gautier is a terrifying, stifling and irreversible finality. Unlike many Romantics before him, Gautier's vision of death is solemn and portentous, proclaiming death as the definitive escape from life's torture. During the time he wrote the work, Gautier was frequenting many cemeteries, which were then expanding rapidly to accommodate the many deaths from epidemics that swept the country. Gautier translates death into a curiously heady, voluptuous, almost exhilarating experience which diverts him momentarily from the gruesome reality and conveys his urgent plea for light over darkness, life over death.

- España (1845) is usually considered the transitional volume between the two phases of Gautier's poetic career. Inspired by the author's summer 1840 visit to Spain, the 43 miscellaneous poems in the collection cover topics including the Spanish language and aspects of Spanish culture and traditions such as music and dance.

- Émaux et Camées (1852), published when Gautier was touring the Middle East, is considered his supreme poetic achievement. The title reflects Gautier's abandonment of the romantic ambition to create a kind of "total" art involving the emotional participation of the reader, in favor of a more modern approach focusing more on the poetic composition's form instead of its content. Originally a collection of 18 poems in 1852, its later editions contained up to 37 poems.

- Dernières Poésies (1872) is a collection of poems that range from earlier pieces to unfinished fragments composed shortly before Gautier's death. This collection is dominated by numerous sonnets dedicated to many of his friends.

Gautier did not consider himself to be dramatist but more of a poet and storyteller. His plays were limited because of the time in which he lived. During the Revolution of 1848, many theaters were closed down and therefore plays were scarce. Most of the plays that dominated the mid century were written by playwrights who insisted on conformity and conventional formulas and catered to cautious middle class audiences. As a result, most of Gautier's plays were never published or reluctantly accepted.

Between the years 1839 and 1850, Gautier wrote all or part of nine different plays:

- Un Voyage en Espagne (1843);

- La Juive de Constantine (1846);

- Regardez mais ne touchez pas (1847) — written less by Gautier than his collaborators;

- Pierrot en Espagne (1847) — Gautier's authorship is uncertain;

- L’Amour souffle où il veut (1850) — not completed;

- Une Larme du diable (1839) ("The Devil's Tear") was written shortly after Gautier's trip to Belgium in 1836. The work is considered an imitation of a Medieval mystery play, a type of drama popular in the 14th century. These plays were usually performed in churches because they were religious in nature. In Gautier's play God cheats a bit to win a bet with Satan. The play is humorous and preaches both in favor and against human love;

- Le Tricorne enchanté (1845; "The Magic Hat") is a play set in the 17th century. The plot involves an old man named Géronte who wishes to marry a beautiful woman who is in love with another man. After much scheming, the old man is duped and the lovers are married;

- La Fausse Conversion (1846) ("The False Conversion") is a satirical play written in prose. It was published in the Revue Des Deux Mondes on March 1. As with many other Gautier plays, the drama was not performed in his lifetime. It takes place in the 18th Century, before the social misery that preceded the French Revolution. La Fausse Conversion is highly anti - feminist and expresses Gautier's opinion that a woman must be a source of pleasure for man or frozen into art;

- Pierrot Posthume (1847) is a brief comedic fantasy inspired by the Italian Commedia dell' arte, popular in France since the 16th century. It involved a typical triangle and ends happily ever after'

- Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835) In September 1833, Gautier was solicited to write a historical romance based on the life of French opera star Mlle Maupin, who was a first rate swordswoman and often went about disguised as a man. Originally, the story was to be about the historical la Maupin, who set fire to a convent for the love of another woman, but later retired to a convent herself, shortly before dying in her thirties. Gautier instead turned the plot into a simple love triangle between a man, d'Albert, and his mistress, Rosette, who both fall in love with Madelaine de Maupin, who is disguised as a man named Théodore. The message behind Gautier's version of the infamous legend is the fundamental pessimism about the human identity, and perhaps the entire Romantic age. The novel consists of seventeen chapters, most in the form of letters written by d'Albert or Madelaine. Most critics focus on the preface of the novel, which preached about Art for art's sake through its dictum that "everything useful is ugly";

- Le Roman de La Momie (1858)'

- Le Capitaine Fracasse (1863) This book was promised to the public in 1836 but finally published in 1863. The novel represents a different era and is a project that Gautier had wanted to complete earlier in this youth. It is centered on a soldier named Fracasse whose adventures portray bouts of chivalry, courage and a sense of adventure. Gautier places the story in his favorite historical era, that of Louis XIII. It is best described as a typical cloak - and - dagger fairy tale where everyone lives happily ever after;

- One of Cleopatra's nights.