<Back to Index>

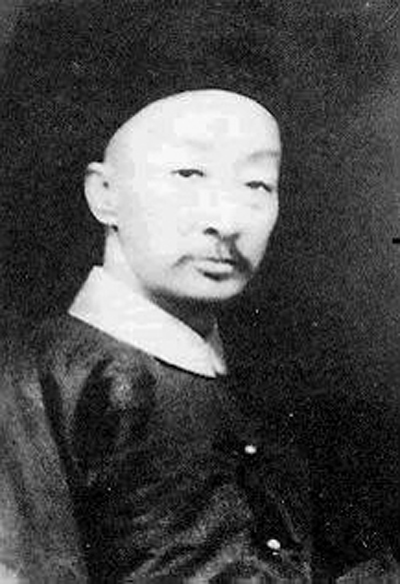

- Viceroy of Zhili Ronglu, 1836

PAGE SPONSOR

Ronglu (Chinese: 荣禄; 6 April 1836 – 11 April 1903) was a Manchu statesman and general during the late Qing dynasty. Born into the powerful Guwalgiya clan of the Plain White Banner in the Eight Banners, he was cousin to Empress Dowager Cixi. He served in a number of important positions in the Imperial Court, including the Zongli Yamen and the Grand Council, Grand Scholar, Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Minister, Minister of Board of War, Nine Gates Infantry Commander, Wuwei Troop Commander that safeguard the military security of the Forbidden City.

Ronglu was born on 6 April 1836. He was the son of Guwalgiya Changshou (瓜爾佳長壽). Ronglu's grandfather, Guwalgiya Tasiha (瓜爾佳塔斯哈), had served in Kashgar as an official.

Before Cixi's marriage as a concubine into the royal family, Ronglu was rumored to have had a love relationship with Cixi. During Cixi's tenure as regent of the Qing Dynasty, Ronglu became one of the leaders of Cixi's conservative faction at the imperial court, and opposed Kang Youwei's Hundred Days' Reform in 1898. Cixi always remembered her cousin's support for her, even when they were young, and rewarded him by allowing his only surviving child, his daughter Youlan, to marry into the imperial clan.

Through his daughter's marriage to Zaifeng, Prince Chun, Ronglu is the maternal grandfather of the Xuantong Emperor.

At 1894, after the First Sino - Japanese War, Ronglu was appointed Peking Land Troop Commander (Chinese: 步军统领), at 1895, he was appointed minister of Zongli Yamen, minister of the Board of War (Chinese: 兵部尚书) and Peking Land Troop Commander. During the Boxer Rebellion, Ronglu was the commander of Wuwei Middle Troop (Chinese: 武卫中军), providing military security for the Forbidden City.

At 1898, Ronlu was appointed Grand Scholar (Chinese: 协办大学士), Viceroy of Zhili, Beiyang Minister (Chinese: 北洋大臣), Minister of Grand Council and Minister of Board of War (Chinese: 兵部), coordinating between Dong Fuxiang, Nie Shicheng, Song Qing and the Yuan Shikai Beiyang Army, and creating Wuwei Troop (Chinese: 武卫军), then appointed Nine Gates Infantry Commander. When Empress Dowager and Guangxu Emperor escaped to Xian during the invasion of the Eight Nation Alliance, Ronglu was ordered to stay in Peking to safeguard the Peking City and the Forbidden City.

On Day Nineteen of May (lunar calendar) 1901, a total of five decrees were issued by the Empress Dowager. Decree No.1 ordered Ronglu to "command various Imperial soldiers, plus Shenjiying, Tiger Gods Division, with Horse cavalry, in addition of Wuwei Middle Troop, to suppress these bandits, to intensify searching patrol; to arrest and execute immediately all criminals with weapons who advocate killing." Decree No.4 of the same day ordered Ronglu to "send efficient troops of Wuwei Middle Troop swiftly, to the Peking Legation Quarter, to protect all the diplomatic buildings."

On 1899, with the approval of Empress Dowager, Ronglu began to build the first modern infantry military force of the Manchu Empire. During the war with the Eight Nation Alliance, Wuwei Troops commanded by Dong Fuxiang, Nie Shicheng and Ronglu himself suffered heavy casualties and since had been disbanded.

Ronglu deliberately sabotaged the performance of the Imperial army during the Boxer Rebellion. When Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops were eager to and could have destroyed the foreigners in the legations, Ronglu stopped them from doing so. The Manchu prince Zaiyi was xenophobic and was friends with Dong Fuxiang. Zaiyi wanted artillery for Dong Fuxiang's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from destroying the legations. When artillery was finally supplied to the Imperial Army and Boxers, it was only done so in limited amounts, Ronglu deliberately held back the rest of them.

It was Ronglu and other moderates, who withdrew the Kansu Muslim warriors from Beijing, in order to let the foreigners march right in. The Muslim troops were feared intensely by the foreigners.

Ronglu also deliberately hid an Imperial Decree from General Nie Shicheng. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers due to the foreign invasion, and also because the population was suffering from the campaign against the Boxers. Due to Ronglu's actions, General Nie continued to fight against the Boxers and killed many of them, while the foreign invaders were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers.

During the war, because parts of the Railway were saved under Ronglu's orders, the foreign invasion army was able to transport itself into China quickly.

Due to Ronglu's sabotage, General Nie was forced to fight the Boxers as the foreign army advanced into China. The fierce Boxer insurgency led General Nie to commit thousands of troops against them, instead of against the foreigners. Nie was already outnumbered by the Allies by 4,000 men. General Nie was blamed for attacking the Boxers, as Ronglu intended to sabotage Nie and let him take all the blame. At the Battle of Tientsin, General Nie decided to take his own life by walking into the range of Allied guns.

Ronglu denied Dong Fuxiang the artillery he could have used to crush the Legations, the foreigners discovered that the Chinese had hundreds of modern made, European Krupp manufactured guns and munitions at their disposal, and deliberately did not use them against the foreigners. One day was all it could have taken for the Chinese to finish off the Legations, and the Chinese could have fired 3,000 shells a day, yet that was only the number they fired for the whole siege.

Dong Fuxiang said himself that "'Jung Lu has the guns which my army needs; with their aid not a stone would be left standing in the whole of the Legation Quarter.", in a meeting with Empress Dowager Cixi, complaining about the issue again.

The Chinese regarded warfare as a conquest for glory between different Generals, each competing for victory. In addition to denying victory to Dong Fuxiang, Ronglu also did not want to win the battle for himself, since he was anti - Boxer and wanted to destroy them, saying "To forestall conflicts with the foreign Powers, we must hasten to purge the metropolitan area of the Boxers. This is important."

Since Ronglu had effectively derailed the Chinese effort to take the legations, and as a result, saved the foreigners within them, he was shocked that he was not welcome to be among them after the war. However, they did not demand that he, unlike Dong Fuxiang, be punished.

The advance of the Boxers upon Peking soon cut off the communications of the foreign ministers with the outside world. But for the timely arrival of some four hundred and fifty marines from the warships it would scarcely have been possible to defend the Legations against the attacks which in a few days commenced. The foreign powers were beginning to realize the critical nature of the situation and poured troops into Tientsin, but the force of two thousand men sent to relieve their fellow countrymen in Peking proved insufficient and was forced to retire with heavy loss. Consequently the legations were "straitly shut up" within the walls of the British Embassy and disaster on a large scale seemed imminent. The chancellor of the Japanese legation, Mr. Sugiyama, was murdered on June 11 and Baron von Ketteler, the German minister, on June 20. The attack, which at times was made with the greatest possible fury, at other times appeared to be half - hearted, and it was apparent that there were divided counsels in the Chinese Court. Later investigation brought out the fact that the reactionary leader, Prince Tuan, was the most inveterate enemy of the besieged, whilst it was to Prince Jung Lu that they owed their eventual escape.

Herbert Henry Gowen in "An Outline History of China: From the Manchu conquest to the recognition of the republic, A.D. 1913"

Up to the 20th of June we had — as already stated — only Boxers armed with sword and spear to fear, but on that day rifles began to be used, and soldiers fired them — notably men belonging to Tung Fuh Hsiang's Kan-suh command. Our longing for the appearance of Admiral Seymour grew intense, and night after night we buoyed ourselves up with calculations founded on the sound of heavy guns in the distance or the appearance of what experts pronounced to be search lights in the sky: soon, however, we gave up all hope of the Admiral's party, but, supposing that the Taku forts had been taken on the 18th, we inferred that a few days later would see a large force marching from Tien-tsin for our relief, and that within a fortnight it would be with us — otherwise, why imperil us at Peking by such premature action at Taku? We were under fire from the 20th to the 25th of June, from the 28th of June to the 18th of July, from the 18th of July to the 2nd of August, and from the 4th to the 14th of August: night and day rifle bullets, cannon balls, and Krupp shells had been poured into the various Legations from the gate in front of the Palace itself, from the very wall of the Imperial City, as well as from numerous nearer points around us, and the assailants on all sides were Chinese soldiers; whether the quiet of the 26th and 27th of June and eighth to 27th of July was or was not ordered by the government we can not say, but the firing during the other periods, close as we were to the Palace, must have been by the orders of the government; and it cost our small number over sixty killed and a hundred wounded! That somebody intervened for our semi - protection seems, however, probable. Attacks were not made by such numbers as the government had at its disposal; they were never pushed home, but always sensed just when we feared they would succeed, and, had the force round us really attacked with thoroughness and determination, we could not have held out a week, perhaps not even a day; and so the explanation that there was some kind of protection — that somebody, probably a wise man who knew what the destruction of the legations would cost empire and dynasty, intervened between the issue of the order for our destruction and the execution of it, and so kept the soldiery playing with us as cats do with mice, the continued and seemingly heavy firing telling the Palace how fiercely we were attacked and how stubbornly we defended ourselves; while its curiously half - hearted character not only gave us the chance to live through it, but also gave any relief forces time to come and extricate us, and thus avert the national calamity which the Palace in its pride and conceit ignored, but which someone, in authority, in his wisdom foresaw and in his discretion sought how to push aside.

Sir Robert Hart in "These from the land of Sinim.": Essays on the Chinese question