<Back to Index>

- Writer Mary Shelley (Wollstonecraft Godwin), 1797

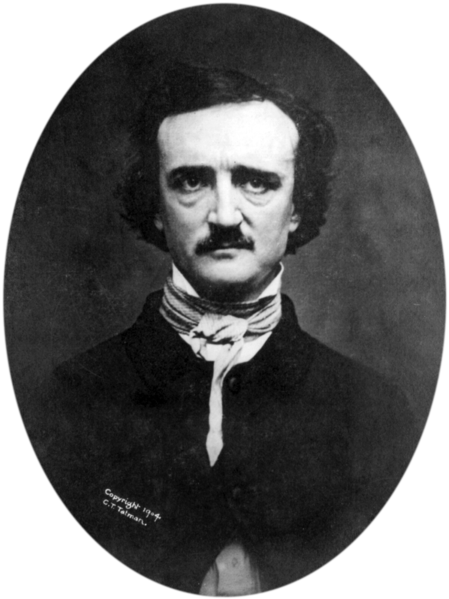

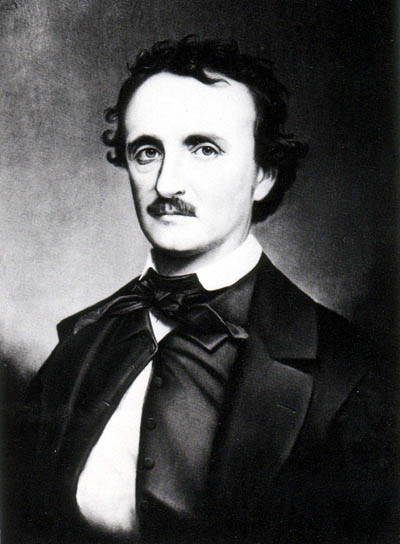

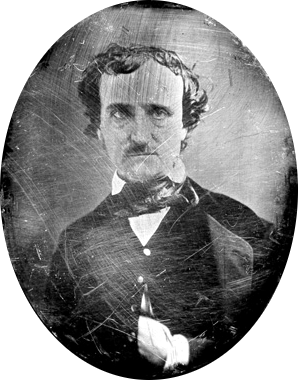

- Writer Edgar Allan Poe, 1809

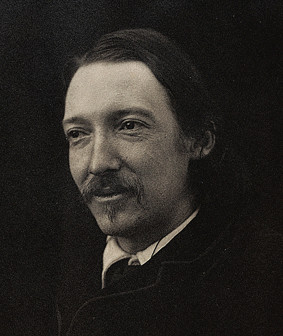

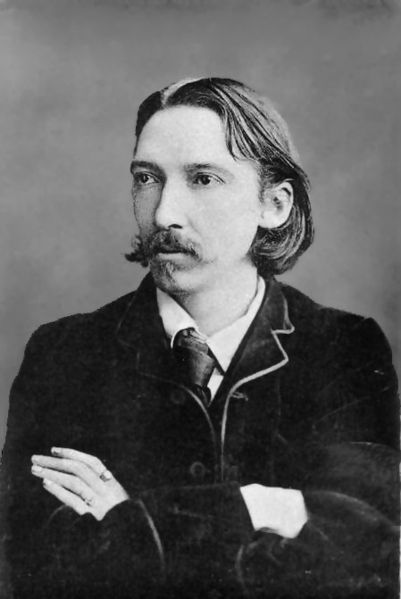

- Writer Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson, 1850

PAGE SPONSOR

Mary Shelley (née Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist, short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). She also edited and promoted the works of her husband, the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her father was the political philosopher William Godwin, and her mother was the philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft.

Mary Godwin's mother died when she was eleven days old; afterwards, she and her older half - sister, Fanny Imlay, were raised by her father. When Mary was four, Godwin married his neighbor, Mary Jane Clairmont. Godwin provided his daughter with a rich, if informal, education, encouraging her to adhere to his liberal political theories. In 1814, Mary Godwin began a romantic relationship with one of her father’s political followers, the married Percy Bysshe Shelley. Together with Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, they left for France and traveled through Europe; upon their return to England, Mary was pregnant with Percy's child. Over the next two years, she and Percy faced ostracism, constant debt, and the death of their prematurely born daughter. They married in late 1816 after the suicide of Percy Shelley's first wife, Harriet.

In 1816, the couple famously spent a summer with Lord Byron, John William Polidori, and Claire Clairmont near Geneva, Switzerland, where Mary conceived the idea for her novel Frankenstein. The Shelleys left Britain in 1818 for Italy, where their second and third children died before Mary Shelley gave birth to her last and only surviving child, Percy Florence. In 1822, her husband drowned when his sailing boat sank during a storm in the Bay of La Spezia. A year later, Mary Shelley returned to England and from then on devoted herself to the upbringing of her son and a career as a professional author. The last decade of her life was dogged by illness, probably caused by the brain tumor that was to kill her at the age of 53.

Until the 1970s, Mary Shelley was known mainly for her efforts to publish Percy Shelley's works and for her novel Frankenstein, which remains widely read and has inspired many theatrical and film adaptations. Recent scholarship has yielded a more comprehensive view of Mary Shelley’s achievements. Scholars have shown increasing interest in her literary output, particularly in her novels, which include the historical novels Valperga (1823) and Perkin Warbeck (1830), the apocalyptic novel The Last Man (1826), and her final two novels, Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837). Studies of her lesser - known works such as the travel book Rambles in Germany and Italy (1844) and the biographical articles for Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829 – 46) support the growing view that Mary Shelley remained a political radical throughout her life. Mary Shelley's works often argue that cooperation and sympathy, particularly as practiced by women in the family, were the ways to reform civil society. This view was a direct challenge to the individualistic Romantic ethos promoted by Percy Shelley and the Enlightenment political theories articulated by her father, William Godwin.

Mary Shelley was born Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin in Somers Town, London, in 1797. She was the second child of the feminist philosopher, educator and writer Mary Wollstonecraft, and the first child of the philosopher, novelist and journalist William Godwin. Wollstonecraft died of puerperal fever ten days after Mary was born. Godwin was left to bring up Mary, along with her older half - sister, Fanny Imlay, Wollstonecraft's child by the American speculator Gilbert Imlay. A year after Wollstonecraft's death, Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798), which he intended as a sincere and compassionate tribute. However, because the Memoirs revealed Wollstonecraft's affairs and her illegitimate child, they were seen as shocking. Mary Godwin read these memoirs and her mother's books, and was brought up to cherish her mother's memory.

Mary's earliest years were happy ones, judging from the letters of William Godwin's housekeeper and nurse, Louisa Jones. But Godwin was often deeply in debt; feeling that he could not raise the children by himself, he cast about for a second wife. In December 1801, he married Mary Jane Clairmont, a well educated woman with two young children of her own — Charles and Claire. Most of Godwin’s friends disliked his new wife, describing her as quick - tempered and quarrelsome; but Godwin was devoted to her, and the marriage was a success. Mary Godwin, on the other hand, came to detest her stepmother. William Godwin's 19th century biographer C. Kegan Paul later suggested that Mrs Godwin had favored her own children over Mary Wollstonecraft’s.

Together, the Godwins started a publishing firm called M.J. Godwin, which sold children's books as well as stationery, maps and games. However, the business did not turn a profit, and Godwin was forced to borrow substantial sums to keep it going. He continued to borrow to pay off earlier loans, compounding his problems. By 1809, Godwin's business was close to failure and he was "near to despair". Godwin was saved from debtor's prison by philosophical devotees such as Francis Place, who lent him further money.

Though Mary Godwin received little formal education, her father tutored her in a broad range of subjects. He often took the children on educational outings, and they had access to his library and to the many intellectuals who visited him, including the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the former vice president of the United States Aaron Burr. Godwin admitted he was not educating the children according to Mary Wollstonecraft's philosophy as outlined in works such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), but Mary Godwin nonetheless received an unusual and advanced education for a girl of the time. She had a governess, a daily tutor, and read many of her father's children's books on Roman and Greek history in manuscript. For six months in 1811, she also attended a boarding school in Ramsgate. Her father described her at fifteen as "singularly bold, somewhat imperious, and active of mind. Her desire of knowledge is great, and her perseverance in everything she undertakes almost invincible."

In June 1812, her father sent Mary to stay with the Dissenting family of the radical William Baxter, near Dundee, Scotland. To Baxter, he wrote, "I am anxious that she should be brought up ... like a philosopher, even like a cynic." Scholars have speculated that she may have been sent away for her health, to remove her from the seamy side of business, or to introduce her to radical politics. Mary Godwin reveled in the spacious surroundings of Baxter's house and in the companionship of his four daughters, and she returned north in the summer of 1813 for a further stay of ten months. In the 1831 introduction to Frankenstein, she recalled: "I wrote then — but in a most common - place style. It was beneath the trees of the grounds belonging to our house, or on the bleak sides of the woodless mountains near, that my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered."

Mary Godwin may have first met the radical poet - philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley in the interval between her two stays in Scotland. By the time she returned home for a second time on 30 March 1814, Percy Shelley had become estranged from his wife and was regularly visiting Godwin, whom he had agreed to bail out of debt. Percy Shelley's radicalism, particularly his economic views, which he had imbibed from Godwin's Political Justice (1793), had alienated him from his wealthy aristocratic family: they wanted him to follow traditional models of the landed aristocracy, and he wanted to donate large amounts of the family's money to schemes intended to help the disadvantaged. Percy Shelley therefore had difficulty gaining access to money until he inherited his estate because his family did not want him wasting it on projects of "political justice". After several months of promises, Shelley announced that he either could not or would not pay off all of Godwin's debts. Godwin was angry and felt betrayed.

Mary and Percy began meeting each other secretly at Mary Wollstonecraft's grave in St Pancras Churchyard, and they fell in love — she was nearly seventeen, he nearly twenty - two. To Mary's dismay, her father disapproved and tried to thwart the relationship and salvage the "spotless fame" of his daughter. At about the same time, Mary's father learned of Shelley's inability to pay off the father's debts. Mary, who later wrote of "my excessive and romantic attachment to my father", was confused. She saw Percy Shelley as an embodiment of her parents' liberal and reformist ideas of the 1790s, particularly Godwin's view that marriage was a repressive monopoly, which he had argued in his 1793 edition of Political Justice but since retracted. On 28 July 1814, the couple secretly left for France, taking Mary's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, with them, but leaving Percy's pregnant wife behind.

After convincing Mary Jane Godwin, who had pursued them to Calais, that they did not wish to return, the trio traveled to Paris, and then, by donkey, mule, carriage and foot, through a France recently ravaged by war, to Switzerland. "It was acting in a novel, being an incarnate romance," Mary Shelley recalled in 1826. As they traveled, Mary and Percy read works by Mary Wollstonecraft and others, kept a joint journal, and continued their own writing. At Lucerne, lack of money forced the three to turn back. They traveled down the Rhine and by land to the Dutch port of Marsluys, arriving at Gravesend, Kent, on 13 September 1814.

The situation awaiting Mary Godwin in England was fraught with complications, some of which she had not foreseen. Either before or during the journey, she had become pregnant. She and Percy now found themselves penniless, and, to Mary's genuine surprise, her father refused to have anything to do with her. The couple moved with Claire into lodgings at Somers Town, and later, Nelson Square. They maintained their intense program of reading and writing and entertained Percy Shelley's friends, such as Thomas Jefferson Hogg and the writer Thomas Love Peacock. Percy Shelley sometimes left home for short periods to dodge creditors. The couple's distraught letters reveal their pain at these separations.

Pregnant and often ill, Mary Godwin had to cope with Percy's joy at the birth of his son by Harriet Shelley in late 1814 and his constant outings with Claire Clairmont. She was partly consoled by the visits of Hogg, whom she disliked at first but soon considered a close friend. Percy Shelley seems to have wanted Mary Godwin and Hogg to become lovers; Mary did not dismiss the idea, since in principle she believed in free love. In practice, however, she loved only Percy Shelley and seems to have ventured no further than flirting with Hogg. On 22 February 1815, she gave birth to a two - months premature baby girl, who was not expected to survive. On 6 March, she wrote to Hogg:

My dearest Hogg my baby is dead — will you come to see me as soon as you can. I wish to see you — It was perfectly well when I went to bed — I awoke in the night to give it suck it appeared to be sleeping so quietly that I would not awake it. It was dead then, but we did not find that out till morning — from its appearance it evidently died of convulsions — Will you come — you are so calm a creature & Shelley is afraid of a fever from the milk — for I am no longer a mother now.

The loss of her child induced acute depression in Mary Godwin, who was haunted by visions of the baby; but she conceived again and had recovered by the summer. With a revival in Percy Shelley's finances after the death of his grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley, the couple holidayed in Torquay and then rented a two storey cottage at Bishopsgate, on the edge of Windsor Great Park. Little is known about this period in Mary Godwin's life, since her journal from May 1815 to July 1816 is lost. At Bishopsgate, Percy wrote his poem Alastor; and on 24 January 1816, Mary gave birth to a second child, William, named after her father and soon nicknamed "Willmouse". In her novel The Last Man, she later imagined Windsor as a Garden of Eden.

In May 1816, Mary Godwin, Percy Shelley, and their son traveled to Geneva with Claire Clairmont. They planned to spend the summer with the poet Lord Byron, whose recent affair with Claire had left her pregnant. The party arrived at Geneva on 14 May 1816, where Mary called herself "Mrs Shelley". Byron joined them on 25 May, with his young physician, John William Polidori, and rented the Villa Diodati, close to Lake Geneva at the village of Cologny; Percy Shelley rented a smaller building called Maison Chapuis on the waterfront nearby. They spent their time writing, boating on the lake, and talking late into the night.

"It proved a wet, ungenial summer", Mary Shelley remembered in 1831, "and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house". Among other subjects, the conversation turned to the experiments of the 18th century natural philosopher and poet Erasmus Darwin, who was said to have animated dead matter, and to galvanism and the feasibility of returning a corpse or assembled body parts to life. Sitting around a log fire at Byron's villa, the company also amused themselves by reading German ghost stories, prompting Byron to suggest they each write their own supernatural tale. Shortly afterwards, in a waking dream, Mary Godwin conceived the idea for Frankenstein:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavor to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.

She began writing what she assumed would be a short story. With Percy Shelley's encouragement, she expanded this tale into her first novel, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, published in 1818. She later described that summer in Switzerland as the moment "when I first stepped out from childhood into life". The episode is fictionalized in Ken Russell's film Gothic (1986).

Since Frankenstein was published anonymously in 1818, readers and critics argued over its origins and the contributions of the two Shelleys to the book. There are differences in the 1818, 1823 and 1831 editions, and Mary Shelley wrote, "I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband, and yet but for his incitement, it would never have taken the form in which it was presented to the world." she wrote. She wrote that the preface to the first edition was Percy's work "as far as I can recollect." James Rieger concluded Percy's "assistance at every point in the book's manufacture was so extensive that one hardly knows whether to regard him as editor or minor collaborator" while Anne K. Mellor later argued Percy only "made many technical corrections and several times clarified the narrative and thematic continuity of the text."

On their return to England in September, Mary and Percy moved — with Claire Clairmont, who took lodgings nearby — to Bath, where they hoped to keep Claire’s pregnancy secret. At Cologny, Mary Godwin had received two letters from her half - sister, Fanny Imlay, who alluded to her "unhappy life"; on 9 October, Fanny wrote an "alarming letter" from Bristol that sent Percy Shelley racing off to search for her, without success. On the morning of 10 October, Fanny Imlay was found dead in a room at a Swansea inn, along with a suicide note and a laudanum bottle. On 10 December, Percy Shelley's wife, Harriet, was discovered drowned in the Serpentine, a lake in Hyde Park, London. Both suicides were hushed up. Harriet’s family obstructed Percy Shelley's efforts — fully supported by Mary Godwin — to assume custody of his two children by Harriet. His lawyers advised him to improve his case by marrying; so he and Mary, who was pregnant again, married on 30 December 1816 at St Mildred's Church, Bread Street, London. Mr and Mrs Godwin were present and the marriage ended the family rift.

Claire Clairmont gave birth to a baby girl on 13 January, at first called Alba, later Allegra. In March of that year, the Chancery Court ruled Percy Shelley morally unfit to assume custody of his children and later placed them with a clergyman's family. Also in March, the Shelleys moved with Claire and Alba to Albion House at Marlow, Buckinghamshire, a large, damp building on the river Thames. There Mary Shelley gave birth to her third child, Clara, on 2 September. At Marlow, they entertained their new friends Marianne and Leigh Hunt, worked hard at their writing, and often discussed politics.

At Marlow, Mary edited the joint journal of the group's 1814 Continental journey, adding material written in Switzerland in 1816, along with Percy's poem "Mont Blanc". The result was the History of a Six Weeks' Tour, published in November 1817. That autumn, Percy Shelley often lived away from home in London to evade creditors. The threat of a debtor's prison, combined with their ill health and fears of losing custody of their children, contributed to the couple's decision to leave England for Italy on 12 March 1818, taking Claire Clairmont and Alba with them. They had no intention of returning.

One of the party's first tasks on arriving in Italy was to hand Alba over to Byron, who was living in Venice. He had agreed to raise her so long as Claire had nothing more to do with her. The Shelleys then embarked on a roving existence, never settling in any one place for long. Along the way, they accumulated a circle of friends and acquaintances who often moved with them. The couple devoted their time to writing, reading, learning, sightseeing and socializing. The Italian adventure was, however, blighted for Mary Shelley by the deaths of both her children — Clara, in September 1818 in Venice, and William, in June 1819 in Rome. These losses left her in a deep depression that isolated her from Percy Shelley, who wrote in his notebook:

- My dearest Mary, wherefore hast thou gone,

- And left me in this dreary world alone?

- Thy form is here indeed — a lovely one —

- But thou art fled, gone down a dreary road

- That leads to Sorrow’s most obscure abode.

- For thine own sake I cannot follow thee

- Do thou return for mine.

For a time, Mary Shelley found comfort only in her writing. The birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, on 12 November 1819, finally lifted her spirits, though she nursed the memory of her lost children till the end of her life.

Italy provided the Shelleys, Byron, and other exiles with a political freedom unattainable at home. Despite its associations with personal loss, Italy became for Mary Shelley "a country which memory painted as paradise". Their Italian years were a time of intense intellectual and creative activity for both Shelleys. While Percy composed a series of major poems, Mary wrote the autobiographical novel Matilda, the historical novel Valperga, and the plays Proserpine and Midas. Mary wrote Valperga to help alleviate her father's financial difficulties, as Percy refused to assist him further. She was often physically ill, however, and prone to depressions. She also had to cope with Percy’s interest in other women, such as Sophia Stacey, Emilia Viviani and Jane Williams. Since Mary Shelley shared his belief in the non - exclusivity of marriage, she formed emotional ties of her own among the men and women of their circle. She became particularly fond of the Greek revolutionary Prince Alexander Mavrocordato and of Jane and Edward Williams.

In December 1818, the Shelleys traveled south with Claire Clairmont and their servants to Naples, where they stayed for three months, receiving only one visitor, a physician. In 1820, they found themselves plagued by accusations and threats from Paolo and Elise Foggi, former servants whom Percy Shelley had dismissed in Naples shortly after the Foggis had married. The pair revealed that on 27 February 1819 in Naples, Percy Shelley had registered as his child by Mary Shelley a two month old baby girl named Elena Adelaide Shelley. The Foggis also claimed that Claire Clairmont was the baby's mother. Biographers have offered various interpretations of these events: that Percy Shelley decided to adopt a local child; that the baby was his by Elise, Claire, or an unknown woman; or that she was Elise’s by Byron. Mary Shelley insisted she would have known if Claire had been pregnant, but it is unclear how much she really knew. The events in Naples, a city Mary Shelley later called a paradise inhabited by devils, remain shrouded in mystery. The only certainty is that she herself was not the child’s mother. Elena Adelaide Shelley died in Naples on 9 June 1820.

In the summer of 1822, a pregnant Mary moved with Percy, Claire, and Edward and Jane Williams to the isolated Villa Magni, at the sea's edge near the hamlet of San Terenzo in the Bay of Lerici. Once they were settled in, Percy broke the "evil news" to Claire that her daughter Allegra had died of typhus in a convent at Bagnacavallo. Mary Shelley was distracted and unhappy in the cramped and remote Villa Magni, which she came to regard as a dungeon. On 16 June, she miscarried, losing so much blood that she nearly died. Rather than wait for a doctor, Percy sat her in a bath of ice to staunch the bleeding, an act the doctor later told him saved her life. All was not well between the couple that summer, however, and Percy spent more time with Jane Williams than with his depressed and debilitated wife. Most of the short poems Shelley wrote at San Terenzo were addressed to Jane rather than to Mary.

The coast offered Percy Shelley and Edward Williams the chance to enjoy their "perfect plaything for the summer", a new sailing boat. The boat had been designed by Daniel Roberts and Edward Trelawny, an admirer of Byron's who had joined the party in January 1822. On 1 July 1822, Percy Shelley, Edward Ellerker Williams, and Captain Daniel Roberts sailed south down the coast to Livorno. There Percy Shelley discussed with Byron and Leigh Hunt the launch of a radical magazine called The Liberal. On 8 July, he and Edward Williams set out on the return journey to Lerici with their eighteen year old boatboy, Charles Vivian. They never reached their destination. A letter arrived at Villa Magni from Hunt to Percy Shelley, dated 8 July, saying, "pray write to tell us how you got home, for they say you had bad weather after you sailed monday & we are anxious". "The paper fell from me," Mary told a friend later. "I trembled all over." She and Jane Williams rushed desperately to Livorno and then to Pisa in the fading hope that their husbands were still alive. Ten days after the storm, three bodies washed up on the coast near Viareggio, midway between Livorno and Lerici. Trelawny, Byron and Hunt cremated Percy Shelley’s corpse on the beach at Viareggio.

After her husband's death, Mary Shelley lived for a year with Leigh Hunt and his family in Genoa, where she often saw Byron and transcribed his poems. She resolved to live by her pen and for her son, but her financial situation was precarious. On 23 July 1823, she left Genoa for England and stayed with her father and stepmother in the Strand until a small advance from her father - in - law enabled her to lodge nearby. Sir Timothy Shelley had at first agreed to support his grandson, Percy Florence, only if he were handed over to an appointed guardian. Mary Shelley rejected this idea instantly. She managed instead to wring out of Sir Timothy a limited annual allowance (which she had to repay when Percy Florence inherited the estate), but to the end of his days he refused to meet her in person and dealt with her only through lawyers. Mary Shelley busied herself with editing her husband's poems, among other literary endeavors, but concern for her son restricted her options. Sir Timothy threatened to stop the allowance if any biography of the poet were published. In 1826, Percy Florence became the legal heir of the Shelley estate after the death of Charles Shelley, his father's son by Harriet Shelley. Sir Timothy raised Mary's allowance from £100 a year to £250 but remained as difficult as ever. Mary Shelley enjoyed the stimulating society of William Godwin's circle, but poverty prevented her from socializing as she wished. She also felt ostracized by those who, like Sir Timothy, still disapproved of her relationship with Percy Bysshe Shelley.

In the summer of 1824, Mary Shelley moved to Kentish Town in north London to be near Jane Williams. She may have been, in the words of her biographer Muriel Spark, "a little in love" with Jane. Jane later disillusioned her by gossiping that Percy had preferred her to Mary, owing to Mary's inadequacy as a wife. At around this time, Mary Shelley was working on her novel, The Last Man (1826); and she assisted a series of friends who were writing memoirs of Byron and Percy Shelley — the beginnings of her attempts to immortalize her husband. She also met the American actor John Howard Payne and the American writer Washington Irving, who intrigued her. Payne fell in love with her and in 1826 asked her to marry him. She refused, saying that after being married to one genius, she could only marry another. Payne accepted the rejection and tried without success to talk his friend Irving into proposing himself. Mary Shelley was aware of Payne's plan, but how seriously she took it is unclear.

In 1827, Mary Shelley was party to a scheme that enabled her friend Isabel Robinson and Isabel's lover, Mary Diana Dods, who wrote under the name David Lyndsay, to embark on a life together in France as man and wife. With the help of Payne, whom she kept in the dark about the details, Mary Shelley obtained false passports for the couple. In 1828, she fell ill with smallpox while visiting them in Paris. Weeks later she recovered, unscarred but without her youthful beauty.

During the period 1827 – 40, Mary Shelley was busy as an editor and writer. She wrote the novels Perkin Warbeck (1830), Lodore (1835) and Falkner (1837). She contributed five volumes of Lives of Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and French authors to Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia. She also wrote stories for ladies' magazines. She was still helping to support her father, and they looked out for publishers for each other. In 1830, she sold the copyright for a new edition of Frankenstein for £60 to Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley for their new Standard Novels series. After her father's death in 1836 at the age of eighty, she began assembling his letters and a memoir for publication, as he had requested in his will; but after two years of work, she abandoned the project. Throughout this period, she also championed Percy Shelley's poetry, promoting its publication and quoting it in her writing. By 1837, Percy's works were well known and increasingly admired. In the summer of 1838 Edward Moxon, the publisher of Tennyson and the son - in - law of Charles Lamb, proposed publishing a collected works of Percy Shelley. Mary was paid £500 to edit the Poetical Works (1838), which Sir Timothy insisted should not include a biography. Mary found a way to tell the story of Percy's life, nonetheless: she included extensive biographical notes about the poems.

Mary Shelley continued to treat potential romantic partners with caution. In 1828, she met and flirted with the French writer Prosper Mérimée, but her one surviving letter to him appears to be a deflection of his declaration of love. She was delighted when her old friend from Italy, Edward Trelawny, returned to England, and they joked about marriage in their letters. Their friendship had altered, however, following her refusal to cooperate with his proposed biography of Percy Shelley; and he later reacted angrily to her omission of the atheistic section of Queen Mab from Percy Shelley's poems. Oblique references in her journals, from the early 1830s until the early 1840s, suggest that Mary Shelley had feelings for the radical politician Aubrey Beauclerk, who may have disappointed her by twice marrying others.

Mary Shelley's first concern during these years was the welfare of Percy Florence. She honored her late husband's wish that his son attend public school, and, with Sir Timothy's grudging help, had him educated at Harrow. To avoid boarding fees, she moved to Harrow on the Hill herself so that Percy could attend as a day scholar. Though Percy went on to Trinity College, Cambridge, and dabbled in politics and the law, he showed no sign of his parents' gifts. He was devoted to his mother, and after he left university in 1841, he came to live with her.

In 1840 and 1842, mother and son traveled together on the continent, journeys that Mary Shelley recorded in Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843 (1844). In 1844, Sir Timothy Shelley finally died at the age of ninety, "falling from the stalk like an overblown flower", as Mary put it. For the first time, she and her son were financially independent, though the estate proved less valuable than they had hoped.

In the mid 1840s, Mary Shelley found herself the target of three separate blackmailers. In 1845, an Italian political exile called Gatteschi, whom she had met in Paris, threatened to publish letters she had sent him. A friend of her son's bribed a police chief into seizing Gatteschi's papers, including the letters, which were then destroyed. Shortly afterwards, Mary Shelley bought some letters written by herself and Percy Bysshe Shelley from a man calling himself G. Byron and posing as the illegitimate son of the late Lord Byron. Also in 1845, Percy Bysshe Shelley's cousin Thomas Medwin approached her claiming to have written a damaging biography of Percy Shelley. He said he would suppress it in return for £250, but Mary Shelley refused.

In 1848, Percy Florence married Jane Gibson St John. The marriage proved a happy one, and Mary Shelley and Jane were fond of each other. Mary lived with her son and daughter - in - law at Field Place, Sussex, the Shelleys' ancestral home, and at Chester Square, London, and accompanied them on travels abroad.

Mary Shelley's last years were blighted by illness. From 1839, she suffered from headaches and bouts of paralysis in parts of her body, which sometimes prevented her from reading and writing. On 1 February 1851, at Chester Square, she died at the age of fifty - three from what her physician suspected was a brain tumor. According to Jane Shelley, Mary Shelley had asked to be buried with her mother and father; but Percy and Jane, judging the graveyard at St Pancras to be "dreadful", chose to bury her instead at St Peter's Church, Bournemouth, near their new home at Boscombe. On the first anniversary of Mary Shelley's death, the Shelleys opened her box - desk. Inside they found locks of her dead children's hair, a notebook she had shared with Percy Bysshe Shelley, and a copy of his poem Adonaïs with one page folded round a silk parcel containing some of his ashes and the remains of his heart.

Mary Shelley lived a literary life. Her father encouraged her to learn to write by composing letters, and her favorite occupation as a child was writing stories. Unfortunately, all of Mary's juvenilia were lost when she ran off with Percy in 1814, and none of her surviving manuscripts can be definitively dated before that year. Her first published work is often thought to have been Mounseer Nongtongpaw, comic verses written for Godwin's Juvenile Library when she was ten and a half; however, the poem is attributed to another writer in the most recent authoritative collection of her works. Percy Shelley enthusiastically encouraged Mary Shelley's writing: "My husband was, from the first, very anxious that I should prove myself worthy of my parentage, and enroll myself on the page of fame. He was forever inciting me to obtain literary reputation."

Certain sections of Mary Shelley's novels are often interpreted as masked rewritings of her life. Critics have pointed to the recurrence of the father – daughter motif in particular as evidence of this autobiographical style. For example, commentators frequently read Mathilda (1820) autobiographically, identifying the three central characters as versions of Mary Shelley, William Godwin and Percy Shelley. Mary Shelley herself confided that she modeled the central characters of The Last Man on her Italian circle. Lord Raymond, who leaves England to fight for the Greeks and dies in Constantinople, is based on Lord Byron; and the utopian Adrian, Earl of Windsor, who leads his followers in search of a natural paradise and dies when his boat sinks in a storm, is a fictional portrait of Percy Bysshe Shelley. However, as she wrote in her review of Godwin's novel Cloudesley (1830), she did not believe that authors "were merely copying from our own hearts". William Godwin regarded his daughter's characters as types rather than portraits from real life. Some modern critics, such as Patricia Clemit and Jane Blumberg, have taken the same view, resisting autobiographical readings of Mary Shelley's works.

Mary Shelley employed the techniques of many different novelistic genres, most vividly the Godwinian novel, Walter Scott's new historical novel, and the Gothic novel. The Godwinian novel, made popular during the 1790s with works such as Godwin's Caleb Williams (1794), "employed a Rousseauvian confessional form to explore the contradictory relations between the self and society", and Frankenstein exhibits many of the same themes and literary devices as Godwin's novel. However, Shelley critiques those Enlightenment ideals that Godwin promotes in his works. In The Last Man, she uses the philosophical form of the Godwinian novel to demonstrate the ultimate meaninglessness of the world. While earlier Godwinian novels had shown how rational individuals could slowly improve society, The Last Man and Frankenstein demonstrate the individual's lack of control over history.

Shelley uses the historical novel to comment on gender relations; for example, Valperga is a feminist version of Scott's masculinist genre. Introducing women into the story who are not part of the historical record, Shelley uses their narratives to question established theological and political institutions. Shelley sets the male protagonist's compulsive greed for conquest in opposition to a female alternative: reason and sensibility. In Perkin Warbeck, Shelley's other historical novel, Lady Gordon stands for the values of friendship, domesticity and equality. Through her, Shelley offers a feminine alternative to the masculine power politics that destroy the male characters. The novel provides a more inclusive historical narrative to challenge the one which usually relates only masculine events.

With the rise of feminist literary criticism in the 1970s, Mary Shelley's works, particularly Frankenstein, began to attract much more attention from scholars. Feminist and psychoanalytic critics were largely responsible for the recovery from neglect of Shelley as a writer. Ellen Moers was one of the first to claim that Shelley's loss of a baby was a crucial influence on the writing of Frankenstein. She argues that the novel is a "birth myth" in which Shelley comes to terms with her guilt for causing her mother's death as well as for failing as a parent. Shelley scholar Anne K. Mellor suggests that, from a feminist viewpoint, it is a story "about what happens when a man tries to have a baby without a woman ... [Frankenstein] is profoundly concerned with natural as opposed to unnatural modes of production and reproduction". Victor Frankenstein's failure as a "parent" in the novel has been read as an expression of the anxieties which accompany pregnancy, giving birth, and particularly maternity.

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar argue in their seminal book The Madwoman in the Attic (1979) that in Frankenstein in particular, Shelley responded to the masculine literary tradition represented by John Milton's Paradise Lost. In their interpretation, Shelley reaffirms this masculine tradition, including the misogyny inherent in it, but at the same time "conceal[s] fantasies of equality that occasionally erupt in monstrous images of rage". Mary Poovey reads the first edition of Frankenstein as part of a larger pattern in Shelley's writing, which begins with literary self - assertion and ends with conventional femininity. Poovey suggests that Frankenstein's multiple narratives enable Shelley to split her artistic persona: she can "express and efface herself at the same time". Shelley's fear of self - assertion is reflected in the fate of Frankenstein, who is punished for his egotism by losing all his domestic ties.

Feminist critics often focus on how authorship itself, particularly female authorship, is represented in and through Shelley's novels. As Mellor explains, Shelley uses the Gothic style not only to explore repressed female sexual desire but also as way to "censor her own speech in Frankenstein". According to Poovey and Mellor, Shelley did not want to promote her own authorial persona and felt deeply inadequate as a writer, and "this shame contributed to the generation of her fictional images of abnormality, perversion and destruction".

Shelley's writings focus on the role of the family in society and women's role within that family. She celebrates the "feminine affections and compassion" associated with the family and suggests that civil society will fail without them. Shelley was "profoundly committed to an ethic of cooperation, mutual dependence, and self - sacrifice". In Lodore, for example, the central story follows the fortunes of the wife and daughter of the title character, Lord Lodore, who is killed in a duel at the end of the first volume, leaving a trail of legal, financial and familial obstacles for the two "heroines" to negotiate. The novel is engaged with political and ideological issues, particularly the education and social role of women. It dissects a patriarchal culture that separated the sexes and pressured women into dependence on men. In the view of Shelley scholar Betty T. Bennett, "the novel proposes egalitarian educational paradigms for women and men, which would bring social justice as well as the spiritual and intellectual means by which to meet the challenges life invariably brings". However, Falkner is the only one of Mary Shelley's novels in which the heroine's agenda triumphs. The novel’s resolution proposes that when female values triumph over violent and destructive masculinity, men will be freed to express the "compassion, sympathy and generosity" of their better natures.

Frankenstein, like much Gothic fiction of the period, mixes a visceral and alienating subject matter with speculative and thought - provoking themes. Rather than focusing on the twists and turns of the plot, however, the novel foregrounds the mental and moral struggles of the protagonist, Victor Frankenstein, and Shelley imbues the text with her own brand of politicized Romanticism, one that criticized the individualism and egotism of traditional Romanticism. Victor Frankenstein is like Satan in Paradise Lost, and Prometheus: he rebels against tradition; he creates life; and he shapes his own destiny. These traits are not portrayed positively; as Blumberg writes, "his relentless ambition is a self - delusion, clothed as quest for truth". He must abandon his family to fulfill his ambition.

Mary Shelley believed in the Enlightenment idea that people could improve society through the responsible exercise of political power, but she feared that the irresponsible exercise of power would lead to chaos. In practice, her works largely criticize the way 18th century thinkers such as her parents believed such change could be brought about. The creature in Frankenstein, for example, reads books associated with radical ideals but the education he gains from them is ultimately useless. Shelley's works reveal her as less optimistic than Godwin and Wollstonecraft; she lacks faith in Godwin's theory that humanity could eventually be perfected.

As literary scholar Kari Lokke writes, The Last Man, more so than Frankenstein, "in its refusal to place humanity at the center of the universe, its questioning of our privileged position in relation to nature ... constitutes a profound and prophetic challenge to Western humanism." Specifically, Mary Shelley's allusions to what radicals believed was a failed revolution in France and the Godwinian, Wollstonecraftian and Burkean responses to it, challenge "Enlightenment faith in the inevitability of progress through collective efforts". As in Frankenstein, Shelley "offers a profoundly disenchanted commentary on the age of revolution, which ends in a total rejection of the progressive ideals of her own generation". Not only does she reject these Enlightenment political ideals, but she also rejects the Romantic notion that the poetic or literary imagination can offer an alternative.

Critics have until recently cited Lodore and Falkner as evidence of increasing conservatism in Mary Shelley's later works. In 1984, Mary Poovey influentially identified the retreat of Mary Shelley’s reformist politics into the "separate sphere" of the domestic. Poovey suggested that Mary Shelley wrote Falkner to resolve her conflicted response to her father's combination of libertarian radicalism and stern insistence on social decorum. Mellor largely agreed, arguing that "Mary Shelley grounded her alternative political ideology on the metaphor of the peaceful, loving, bourgeois family. She thereby implicitly endorsed a conservative vision of gradual evolutionary reform." This vision allowed women to participate in the public sphere but it inherited the inequalities inherent in the bourgeois family.

However, in the last decade or so this view has been challenged. For example, Bennett claims that Mary Shelley's works reveal a consistent commitment to Romantic idealism and political reform and Jane Blumberg's study of Shelley's early novels argues that her career cannot be easily divided into radical and conservative halves. She contends that "Shelley was never a passionate radical like her husband and her later lifestyle was not abruptly assumed nor was it a betrayal. She was in fact challenging the political and literary influences of her circle in her first work." In this reading, Shelley's early works are interpreted as a challenge to Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley's radicalism. Victor Frankenstein's "thoughtless rejection of family", for example, is seen as evidence of Shelley's constant concern for the domestic.

In the 1820s and 1830s, Mary Shelley frequently wrote short stories for gift books or annuals, including sixteen for The Keepsake, which was aimed at middle class women and bound in silk, with gilt - edged pages. Mary Shelley's work in this genre has been described as that of a "hack writer" and "wordy and pedestrian". However, critic Charlotte Sussman points out that other leading writers of the day, such as the Romantic poets William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, also took advantage of this profitable market. She explains that "the annuals were a major mode of literary production in the 1820s and 1830s", with The Keepsake the most successful.

Many of Shelley's stories are set in places or times far removed from early 19th century Britain, such as Greece and the reign of Henry IV of France. Shelley was particularly interested in "the fragility of individual identity" and often depicted "the way a person's role in the world can be cataclysmically altered either by an internal emotional upheaval, or by some supernatural occurrence that mirrors an internal schism". In her stories, female identity is tied to a woman's short lived value in the marriage market while male identity can be sustained and transformed through the use of money. Although Mary Shelley wrote twenty - one short stories for the annuals between 1823 and 1839, she always saw herself, above all, as a novelist. She wrote to Leigh Hunt, "I write bad articles which help to make me miserable — but I am going to plunge into a novel and hope that its clear water will wash off the mud of the magazines."

When they ran off to France in the summer of 1814, Mary Godwin and Percy Shelley began a joint journal, which they published in 1817 under the title History of a Six Weeks' Tour, adding four letters, two by each of them, based on their visit to Geneva in 1816, along with Percy Shelley's poem "Mont Blanc". The work celebrates youthful love and political idealism and consciously follows the example of Mary Wollstonecraft and others who had combined traveling with writing. The perspective of the History is philosophical and reformist rather than that of a conventional travelogue; in particular, it addresses the effects of politics and war on France. The letters the couple wrote on the second journey confront the "great and extraordinary events" of the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo after his "Hundred Days" return in 1815. They also explore the sublimity of Lake Geneva and Mont Blanc as well as the revolutionary legacy of the philosopher and novelist Jean - Jacques Rousseau.

Mary Shelley's last full length book, written in the form of letters and published in 1844, was Rambles in Germany and Italy in 1840, 1842 and 1843, which recorded her travels with her son Percy Florence and his university friends. In Rambles, Shelley follows the tradition of Mary Wollstonecraft's Letters Written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and her own A History of a Six Weeks' Tour in mapping her personal and political landscape through the discourse of sensibility and sympathy. For Shelley, building sympathetic connections between people is the way to build civil society and to increase knowledge: "knowledge, to enlighten and free the mind from clinging deadening prejudices — a wider circle of sympathy with our fellow - creatures; — these are the uses of travel". Between observations on scenery, culture, and "the people, especially in a political point of view", she uses the travelogue form to explore her roles as a widow and mother and to reflect on revolutionary nationalism in Italy. She also records her "pilgrimage" to scenes associated with Percy Shelley. According to critic Clarissa Orr, Mary Shelley's adoption of a persona of philosophical motherhood gives Rambles the unity of a prose poem, with "death and memory as central themes". At the same time, Shelley makes an egalitarian case against monarchy, class distinctions, slavery and war.

Between 1832 and 1839, Mary Shelley wrote many biographies of notable Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and French men and a few women for Dionysius Lardner's Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men. These formed part of Lardner's Cabinet Cyclopaedia, one of the best of many such series produced in the 1820s and 1830s in response to growing middle class demand for self education. Until the republication of these essays in 2002, their significance within her body of work was not appreciated. In the view of literary scholar Greg Kucich, they reveal Mary Shelley's "prodigious research across several centuries and in multiple languages", her gift for biographical narrative, and her interest in the "emerging forms of feminist historiography". Shelley wrote in a biographical style popularized by the 18th century critic Samuel Johnson in his Lives of the Poets (1779 – 81), combining secondary sources, memoir and anecdote, and authorial evaluation. She records details of each writer's life and character, quotes their writing in the original as well as in translation, and ends with a critical assessment of their achievement.

For Shelley, biographical writing was supposed to, in her words, "form as it were a school in which to study the philosophy of history", and to teach "lessons". Most frequently and importantly, these lessons consisted of criticisms of male dominated institutions such as primogeniture. Shelley emphasizes domesticity, romance, family, sympathy and compassion in the lives of her subjects. Her conviction that such forces could improve society connects her biographical approach with that of other early feminist historians such as Mary Hays and Anna Jameson. Unlike her novels, most of which had an original print run of several hundred copies, the Lives had a print run of about 4,000 for each volume: thus, according to Kucich, Mary Shelley's "use of biography to forward the social agenda of women's historiography became one of her most influential political interventions".

Soon after Percy Shelley’s death, Mary Shelley determined to write his biography. In a letter of 17 November 1822, she announced: "I shall write his life — & thus occupy myself in the only manner from which I can derive consolation." However, her father - in - law, Sir Timothy Shelley, effectively banned her from doing so. Mary began her fostering of Percy's poetic reputation in 1824 with the publication of his Posthumous Poems. In 1839, while she was working on the Lives, she prepared a new edition of his poetry, which became, in the words of literary scholar Susan J. Wolfson, "the canonizing event" in the history of her husband's reputation. The following year, Mary Shelley edited a volume of her husband's essays, letters, translations, and fragments, and throughout the 1830s, she introduced his poetry to a wider audience by publishing assorted works in the annual The Keepsake.

Evading Sir Timothy's ban on a biography, Mary Shelley often included in these editions her own annotations and reflections on her husband's life and work. "I am to justify his ways," she had declared in 1824; "I am to make him beloved to all posterity." It was this goal, argues Blumberg, that led her to present Percy's work to the public in the "most popular form possible". To tailor his works for a Victorian audience, she cast Percy Shelley as a lyrical rather than a political poet. As Mary Favret writes, "the disembodied Percy identifies the spirit of poetry itself". Mary glossed Percy's political radicalism as a form of sentimentalism, arguing that his republicanism arose from sympathy for those who were suffering. She inserted romantic anecdotes of his benevolence, domesticity and love of the natural world. Portraying herself as Percy's "practical muse", she also noted how she had suggested revisions as he wrote.

Despite the emotions stirred by this task, Mary Shelley arguably proved herself in many respects a professional and scholarly editor. Working from Percy's messy, sometimes indecipherable, notebooks, she attempted to form a chronology for his writings, and she included poems, such as Epipsychidion, addressed to Emilia Viviani, which she would rather have left out. She was forced, however, into several compromises, and, as Blumberg notes, "modern critics have found fault with the edition and claim variously that she miscopied, misinterpreted, purposely obscured, and attempted to turn the poet into something he was not". According to Wolfson, Donald Reiman, a modern editor of Percy Bysshe Shelley's works, still refers to Mary Shelley's editions, while acknowledging that her editing style belongs "to an age of editing when the aim was not to establish accurate texts and scholarly apparatus but to present a full record of a writer's career for the general reader". In principle, Mary Shelley believed in publishing every last word of her husband's work; but she found herself obliged to omit certain passages, either by pressure from her publisher, Edward Moxon, or in deference to public propriety. For example, she removed the atheistic passages from Queen Mab for the first edition. After she restored them in the second edition, Moxon was prosecuted and convicted of blasphemous libel, though he escaped punishment. Mary Shelley's omissions provoked criticism, often stinging, from members of Percy Shelley's former circle, and reviewers accused her of, among other things, indiscriminate inclusions. Her notes have nevertheless remained an essential source for the study of Percy Shelley's work. As Bennett explains, "biographers and critics agree that Mary Shelley's commitment to bring Shelley the notice she believed his works merited was the single, major force that established Shelley's reputation during a period when he almost certainly would have faded from public view".

In her own lifetime, Mary Shelley was taken seriously as a writer, though reviewers often missed her writings' political edge. After her death, however, she was chiefly remembered as the wife of Percy Bysshe Shelley and as the author of Frankenstein. In fact, in the introduction to her letters published in 1945, editor Frederick Jones wrote, "a collection of the present size could not be justified by the general quality of the letters or by Mary Shelley's importance as a writer. It is as the wife of [Percy Bysshe Shelley] that she excites our interest." This attitude had not disappeared by 1980 when Betty T. Bennett published the first volume of Mary Shelley's complete letters. As she explains, "the fact is that until recent years scholars have generally regarded Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley as a result: William Godwin's and Mary Wollstonecraft's daughter who became Shelley's Pygmalion." It was not until Emily Sunstein's Mary Shelley: Romance and Reality in 1989 that a full length scholarly biography was published.

The attempts of Mary Shelley's son and daughter - in - law to "Victorianize" her memory by censoring biographical documents contributed to a perception of Mary Shelley as a more conventional, less reformist figure than her works suggest. Her own timid omissions from Percy Shelley's works and her quiet avoidance of public controversy in her later years added to this impression. Commentary by Hogg, Trelawny, and other admirers of Percy Shelley also tended to downplay Mary Shelley's radicalism. Trelawny's Records of Shelley, Byron, and the Author (1878) praised Percy Shelley at the expense of Mary, questioning her intelligence and even her authorship of Frankenstein. Lady Shelley, Percy Florence's wife, responded in part by presenting a severely edited collection of letters she had inherited, published privately as Shelley and Mary in 1882.

From Frankenstein's first theatrical adaptation in 1823 to the cinematic adaptations of the 20th century, including the first cinematic version in 1910 and now famous versions such as James Whale's 1931 Frankenstein, Mel Brooks' 1974 Young Frankenstein, and Kenneth Branagh's 1994 Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, many audiences first encounter the work of Mary Shelley through adaptation. Over the course of the 19th century, Mary Shelley came to be seen as a one - novel author at best, rather than as the professional writer she was; most of her works have remained out of print until the last thirty years, obstructing a larger view of her achievement. In recent decades, the republication of almost all her writing has stimulated a new recognition of its value. Her habit of intensive reading and study, revealed in her journals and letters and reflected in her works, is now better appreciated. Shelley's conception of herself as an author has also been recognized; after Percy's death, she wrote of her authorial ambitions: "I think that I can maintain myself, and there is something inspiriting in the idea." Scholars now consider Mary Shelley to be a major Romantic figure, significant for her literary achievement and her political voice as a woman and a liberal.

Edgar Allan Poe (born Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American author, poet, editor and literary critic, considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story and is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre. He is further credited with contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career.

He was born as Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts; he was orphaned young when his mother died shortly after his father abandoned the family. Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan, of Richmond, Virginia, but they never formally adopted him. He attended the University of Virginia for one semester but left due to lack of money. After enlisting in the Army and later failing as an officer's cadet at West Point, Poe parted ways with the Allans. His publishing career began humbly, with an anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only to "a Bostonian".

Poe switched his focus to prose and spent the next several years working for literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of literary criticism. His work forced him to move among several cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York City. In Baltimore in 1835, he married Virginia Clemm, his 13 year old cousin. In January 1845 Poe published his poem, "The Raven", to instant success. His wife died of tuberculosis two years after its publication. He began planning to produce his own journal, The Penn (later renamed The Stylus), though he died before it could be produced. On October 7, 1849, at age 40, Poe died in Baltimore; the cause of his death is unknown and has been variously attributed to alcohol, brain congestion, cholera, drugs, heart disease, rabies, suicide, tuberculosis, and other agents.

Poe and his works influenced literature in the United States and around the world, as well as in specialized fields, such as cosmology and cryptography. Poe and his work appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. A number of his homes are dedicated museums today. The Mystery Writers of America present an annual award known as the Edgar Award for distinguished work in the mystery genre.

He was born Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the second child of English born actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe, Jr. He had an elder brother, William Henry Leonard Poe, and a younger sister, Rosalie Poe. Their grandfather, David Poe, Sr., had emigrated from Cavan, Ireland, to America around the year 1750. Edgar may have been named after a character in William Shakespeare's King Lear, a play the couple was performing in 1809. His father abandoned their family in 1810, and his mother died a year later from consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis). Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful Scottish merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods including tobacco, cloth, wheat, tombstones and slaves. The Allans served as a foster family and gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe", though they never formally adopted him.

The Allan family had Poe baptized in the Episcopal Church in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son. The family, including Poe and Allan's wife, Frances Valentine Allan, sailed to Britain in 1815. Poe attended the grammar school in Irvine, Scotland (where John Allan was born) for a short period in 1815, before rejoining the family in London in 1816. There he studied at a boarding school in Chelsea until summer 1817. He was subsequently entered at the Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School at Stoke Newington, then a suburb four miles (6 km) north of London.

Poe moved back with the Allans to Richmond, Virginia, in 1820. In 1824 Poe served as the lieutenant of the Richmond youth honor guard as Richmond celebrated the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette. In March 1825, John Allan's uncle and business benefactor William Galt, said to be one of the wealthiest men in Richmond, died and left Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000. By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two story brick home named Moldavia. Poe may have become engaged to Sarah Elmira Royster before he registered at the one year old University of Virginia in February 1826 to study languages. The university, in its infancy, was established on the ideals of its founder, Thomas Jefferson. It had strict rules against gambling, horses, guns, tobacco and alcohol, but these rules were generally ignored. Jefferson had enacted a system of student self government, allowing students to choose their own studies, make their own arrangements for boarding, and report all wrongdoing to the faculty. The unique system was still in chaos, and there was a high dropout rate. During his time there, Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over gambling debts. Poe claimed that Allan had not given him sufficient money to register for classes, purchase texts and procure and furnish a dormitory. Allan did send additional money and clothes, but Poe's debts increased. Poe gave up on the university after a year, and, not feeling welcome in Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married Alexander Shelton, he traveled to Boston in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer. At some point he started using the pseudonym Henri Le Rennet.

Unable to support himself, on May 27, 1827, Poe enlisted in the United States Army as a private. Using the name "Edgar A. Perry", he claimed he was 22 years old even though he was 18. He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor for five dollars a month. That same year, he released his first book, a 40 page collection of poetry, Tamerlane and Other Poems, attributed with the byline "by a Bostonian". Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention. Poe's regiment was posted to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, and traveled by ship on the brig Waltham on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer", an enlisted tradesman who prepared shells for artillery, and had his monthly pay doubled. After serving for two years and attaining the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery (the highest rank a non commissioned officer can achieve), Poe sought to end his five year enlistment early. He revealed his real name and his circumstances to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard. Howard would only allow Poe to be discharged if he reconciled with John Allan and wrote a letter to Allan, who was unsympathetic. Several months passed and pleas to Allan were ignored; Allan may not have written to Poe even to make him aware of his foster mother's illness. Frances Allan died on February 28, 1829, and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, John Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Poe finally was discharged on April 15, 1829, after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him. Before entering West Point, Poe moved back to Baltimore for a time, to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter, Virginia Eliza Clemm (Poe's first cousin), his brother Henry, and his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe. Meanwhile, Poe published his second book, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, in Baltimore in 1829.

Poe traveled to West Point and matriculated as a cadet on July 1, 1830. In October 1830, John Allan married his second wife, Louisa Patterson. The marriage, and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of affairs, led to the foster father finally disowning Poe. Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting court martialed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. Poe tactically pled not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing he would be found guilty.

He left for New York in February 1831, and released a third volume of poems, simply titled Poems. The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point, many of whom donated 75 cents to the cause, raising a total of $170. They may have been expecting verses similar to the satirical ones Poe had been writing about commanding officers. Printed by Elam Bliss of New York, it was labeled as "Second Edition" and included a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated." The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems including early versions of "To Helen", "Israfel" and "The City in the Sea". He returned to Baltimore, to his aunt, brother and cousin, in March 1831. His elder brother Henry, who had been in ill health in part due to problems with alcoholism, died on August 1, 1831.

After his brother's death, Poe began more earnest attempts to start his career as a writer. He chose a difficult time in American publishing to do so. He was the first well known American to try to live by writing alone and was hampered by the lack of an international copyright law. Publishers often pirated copies of British works rather than paying for new work by Americans. The industry was also particularly hurt by the Panic of 1837. Despite a booming growth in American periodicals around this time period, fueled in part by new technology, many did not last beyond a few issues and publishers often refused to pay their writers or paid them much later than they promised. Poe, throughout his attempts to live as a writer, repeatedly had to resort to humiliating pleas for money and other assistance.

After his early attempts at poetry, Poe had turned his attention to prose. He placed a few stories with a Philadelphia publication and began work on his only drama, Politian. The Baltimore Saturday Visiter awarded Poe a prize in October 1833 for his short story "MS. Found in a Bottle". The story brought him to the attention of John P. Kennedy, a Baltimorean of considerable means. He helped Poe place some of his stories, and introduced him to Thomas W. White, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. Poe became assistant editor of the periodical in August 1835, but was discharged within a few weeks for having been caught drunk by his boss. Returning to Baltimore, Poe secretly married Virginia, his cousin, on September 22, 1835. He was 26 and she was 13, though she is listed on the marriage certificate as being 21. Reinstated by White after promising good behavior, Poe went back to Richmond with Virginia and her mother. He remained at the Messenger until January 1837. During this period, Poe claimed that its circulation increased from 700 to 3,500. He published several poems, book reviews, critiques and stories in the paper. On May 16, 1836, he had a second wedding ceremony in Richmond with Virginia Clemm, this time in public.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was published and widely reviewed in 1838. In the summer of 1839, Poe became assistant editor of Burton's Gentleman's Magazine. He published numerous articles, stories and reviews, enhancing his reputation as a trenchant critic that he had established at the Southern Literary Messenger. Also in 1839, the collection Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was published in two volumes, though he made little money off of it and it received mixed reviews. Poe left Burton's after about a year and found a position as assistant at Graham's Magazine.

In June 1840, Poe published a prospectus announcing his intentions to start his own journal, The Stylus. Originally, Poe intended to call the journal The Penn, as it would have been based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the June 6, 1840 issue of Philadelphia's Saturday Evening Post, Poe bought advertising space for his prospectus: "Prospectus of the Penn Magazine, a Monthly Literary journal to be edited and published in the city of Philadelphia by Edgar A. Poe." The journal was never produced before Poe's death. Around this time, he attempted to secure a position with the Tyler administration, claiming he was a member of the Whig Party. He hoped to be appointed to the Custom House in Philadelphia with help from President Tyler's son Robert, an acquaintance of Poe's friend Frederick Thomas. Poe failed to show up for a meeting with Thomas to discuss the appointment in mid September 1842, claiming to have been sick, though Thomas believed he had been drunk. Though he was promised an appointment, all positions were filled by others.

One evening in January 1842, Virginia showed the first signs of consumption, now known as tuberculosis, while singing and playing the piano. Poe described it as breaking a blood vessel in her throat. She only partially recovered. Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of Virginia's illness. He left Graham's and attempted to find a new position, for a time angling for a government post. He returned to New York, where he worked briefly at the Evening Mirror before becoming editor of the Broadway Journal and, later, sole owner. There he alienated himself from other writers by publicly accusing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism, though Longfellow never responded. On January 29, 1845, his poem "The Raven" appeared in the Evening Mirror and became a popular sensation. Though it made Poe a household name almost instantly, he was paid only $9 for its publication. It was concurrently published in The American Review: A Whig Journal under the pseudonym "Quarles".

The Broadway Journal failed in 1846. Poe moved to a cottage in the Fordham section of The Bronx, New York. That home, known today as the "Poe Cottage", is on the southeast corner of the Grand Concourse and Kingsbridge Road. Virginia died there on January 30, 1847. Biographers and critics often suggest that Poe's frequent theme of the "death of a beautiful woman" stems from the repeated loss of women throughout his life, including his wife.

Increasingly unstable after his wife's death, Poe attempted to court the poet Sarah Helen Whitman, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe's drinking and erratic behavior. However, there is also strong evidence that Whitman's mother intervened and did much to derail their relationship. Poe then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Elmira Royster.

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found on the streets of Baltimore delirious, "in great distress, and... in need of immediate assistance", according to the man who found him, Joseph W. Walker. He was taken to the Washington College Hospital, where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849, at 5:00 in the morning. Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition, and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own. Poe is said to have repeatedly called out the name "Reynolds" on the night before his death, though it is unclear to whom he was referring. Some sources say Poe's final words were "Lord help my poor soul." All medical records, including his death certificate, have been lost. Newspapers at the time reported Poe's death as "congestion of the brain" or "cerebral inflammation", common euphemisms for deaths from disreputable causes such as alcoholism. The actual cause of death remains a mystery. Speculation has included delirium tremens, heart disease, epilepsy, syphilis, meningeal inflammation, cholera and rabies. One theory, dating from 1872, indicates that cooping – in which unwilling citizens who were forced to vote for a particular candidate were occasionally killed – was the cause of Poe's death.

The day Edgar Allan Poe was buried, a long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed "Ludwig". It was soon published throughout the country. The piece began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it." "Ludwig" was soon identified as Rufus Wilmot Griswold, an editor, critic and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became Poe's literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.

Rufus Griswold wrote a biographical article of Poe called "Memoir of the Author", which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. Griswold depicted Poe as a depraved, drunk, drug - addled madman and included Poe's letters as evidence. Many of his claims were either lies or distorted half truths. For example, it is now known that Poe was not a drug addict. Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well, but it became a popularly accepted one. This occurred in part because it was the only full biography available and was widely reprinted and in part because readers thrilled at the thought of reading works by an "evil" man. Letters that Griswold presented as proof of this depiction of Poe were later revealed as forgeries.

Poe's best known fiction works are Gothic, a genre he followed to appease the public taste. His most recurring themes deal with questions of death, including its physical signs, the effects of decomposition, concerns of premature burial, the reanimation of the dead, and mourning. Many of his works are generally considered part of the dark romanticism genre, a literary reaction to transcendentalism, which Poe strongly disliked. He referred to followers of the movement as "Frog - Pondians" after the pond on Boston Common. and ridiculed their writings as "metaphor - run mad," lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake." Poe once wrote in a letter to Thomas Holley Chivers that he did not dislike Transcendentalists, "only the pretenders and sophists among them."

Beyond horror, Poe also wrote satires, humor tales and hoaxes. For comic effect, he used irony and ludicrous extravagance, often in an attempt to liberate the reader from cultural conformity. In fact, "Metzengerstein", the first story that Poe is known to have published, and his first foray into horror, was originally intended as a burlesque satirizing the popular genre. Poe also reinvented science fiction, responding in his writing to emerging technologies such as hot air balloons in "The Balloon - Hoax".

Poe wrote much of his work using themes aimed specifically at mass market tastes. To that end, his fiction often included elements of popular pseudosciences such as phrenology and physiognomy.

Poe's writing reflects his literary theories, which he presented in his criticism and also in essays such as "The Poetic Principle". He disliked didacticism and allegory, though he believed that meaning in literature should be an undercurrent just beneath the surface. Works with obvious meanings, he wrote, cease to be art. He believed that work of quality should be brief and focus on a specific single effect. To that end, he believed that the writer should carefully calculate every sentiment and idea.

In "The Philosophy of Composition", an essay in which Poe describes his method in writing "The Raven", he claims to have strictly followed this method. It has been questioned, however, whether he really followed this system. T.S. Eliot said: "It is difficult for us to read that essay without reflecting that if Poe plotted out his poem with such calculation, he might have taken a little more pains over it: the result hardly does credit to the method." Biographer Joseph Wood Krutch described the essay as "a rather highly ingenious exercise in the art of rationalization".

During his lifetime, Poe was mostly recognized as a literary critic. Fellow critic James Russell Lowell called him "the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America", suggesting – rhetorically – that he occasionally used prussic acid instead of ink. Poe's caustic reviews earned him the epithet "Tomahawk Man". A favorite target of Poe's criticism was Boston's then acclaimed poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who was often defended by his literary friends in what would later be called "The Longfellow War". Poe accused Longfellow of "the heresy of the didactic”, writing poetry that was preachy, derivative and thematically plagiarized. Poe correctly predicted that Longfellow's reputation and style of poetry would decline, concluding that "We grant him high qualities, but deny him the Future".

Poe was also known as a writer of fiction and became one of the first American authors of the 19th century to become more popular in Europe than in the United States. Poe is particularly respected in France, in part due to early translations by Charles Baudelaire. Baudelaire's translations became definitive renditions of Poe's work throughout Europe.

Poe's early detective fiction tales featuring C. Auguste Dupin laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed.... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?" The Mystery Writers of America have named their awards for excellence in the genre the "Edgars". Poe's work also influenced science fiction, notably Jules Verne, who wrote a sequel to Poe's novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket called An Antarctic Mystery, also known as The Sphinx of the Ice Fields. Science fiction author H.G. Wells noted, "Pym tells what a very intelligent mind could imagine about the south polar region a century ago."

Like many famous artists, Poe's works have spawned innumerable imitators. One interesting trend among imitators of Poe, however, has been claims by clairvoyants or psychics to be "channeling" poems from Poe's spirit. One of the most notable of these was Lizzie Doten, who in 1863 published Poems from the Inner Life, in which she claimed to have "received" new compositions by Poe's spirit. The compositions were re-workings of famous Poe poems such as "The Bells", but which reflected a new, positive outlook.

Even so, Poe has received not only praise, but criticism as well. This is partly because of the negative perception of his personal character and its influence upon his reputation. William Butler Yeats was occasionally critical of Poe and once called him "vulgar". Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson reacted to "The Raven" by saying, "I see nothing in it" and derisively referred to Poe as "the jingle man". Aldous Huxley wrote that Poe's writing "falls into vulgarity" by being "too poetical" — the equivalent of wearing a diamond ring on every finger.