<Back to Index>

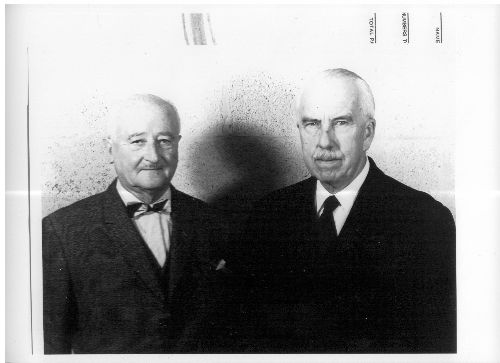

- Codebreaker Alfred Dillwyn "Dilly" Knox, 1884

- Brigadier of the British Army John Hessell Tiltman, 1894

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Dillwyn 'Dilly' Knox, CMG (23 July 1884 27 February 1943) was a classics scholar at King's College, Cambridge, and a British code breaker. He was a member of the World War I Room 40 code breaking unit, and later at Bletchley Park he worked on the cryptanalysis of Enigma ciphers until his death in 1943.

Dillwyn Knox, the fourth of six children, was the son of Edmund Arbuthnott Knox, tutor at Merton College and later Bishop of Manchester; he was the brother of Ronald Knox, E.V. Knox and Wilfred L. Knox. He was the father of Oliver Arbuthnot Knox and Christopher Maynard Knox.

Dillwyn known as "Dilly" Knox was educated at Summer Fields School, Oxford, and then Eton College. He studied classics at King's College, Cambridge, from 1903, and in 1909 was elected a Fellow following the death of Walter Headlam, from whom he inherited extensive research into the works of Herodas. While an undergraduate he was friends with Lytton Strachey and Maynard Keynes. Knox privately coached Harold Macmillan, the future Prime Minister at King's for a few weeks in 1910, but Macmillan found him "austere and uncongenial".

During World War I, Knox was recruited to the Royal Navy's cryptological effort in Room 40 of the Admiralty Old Building, where among other tasks he was involved in breaking the Zimmermann Telegram which brought the U.S.A. into the war.

Between the two World Wars Knox worked on the great commentary on Herodas that had been started by Headlam, damaging his eyesight while studying the British Museum's collection of papyrus fragments, but finally managing to decipher the text of the Herodas papyri. The Knox - Headlam edition of Herodas finally appeared in 1922. He married in 1920, forgetting to invite his brothers to his wedding.

During World War I he had been elected Librarian at King's College, but never took up the appointment. After the war Knox intended to resume his researches at Kings, but he was persuaded by his wife to remain at his secret work; indeed, so secret was this work that his own children had no idea, until many years after his death, what he did for a living, and his contribution to the war effort.

In 1937 he cracked the code of the commercial Enigma machines used by Franco's Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, but knowledge of this breakthrough was not passed on to the Republicans.

Knox was one of the British participants in the Polish - French - British conference held on July 25, 1939, at the Polish Cipher Bureau facility at Pyry, south of Warsaw, Poland, in which the Poles disclosed to their French and British allies their achievements in Enigma decryption. Knox was chagrined but grateful to learn how simple was the solution of the Enigma's entry ring (standard alphabetical order). After the meeting, he sent the Polish cryptologists a very gracious note in Polish, on official British government stationery, thanking them for their assistance, and enclosing a beautiful scarf featuring a picture of a Derby race, and a set of paper 'batons' that he had presumably used in his attempts to break the German Enigma.

To break non - steckered Enigma machines (those without a plugboard), Knox used a system known as 'rodding', a linguistic as opposed to mathematical way of breaking codes. This technique worked on the Enigma used by the Italian Navy and the German Abwehr. Knox worked in 'the Cottage', next door to the Bletchley Park mansion, as head of a research section, which contributed significantly to cryptanalysis of the Enigma.

Knox's work was cut short when he fell ill with lymph cancer.

When he became unable to travel to Bletchley Park, he continued his

cryptographic work from his home in Hughenden, Buckinghamshire, where he

received the CMG. He died on 27 February 1943. A biography of Knox, written by Mavis Batey, one of 'Dilly's girls', the female code breakers who worked with him, was published in September 2009.

Knox is shown recruiting Alan Turing to Bletchley Park in Hugh Whitemore's play Breaking the Code (1986). In the 1996 TV film, he is portrayed by Richard Johnson.

Brigadier John Hessell Tiltman MC (25 May 1894 10 August 1982) was a British Army officer who worked in intelligence, often at or with the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) starting in the 1920s. His intelligence work was largely connected with cryptography, and he showed exceptional skill at cryptanalysis. His work in association with Bill Tutte on the cryptanalysis of the Lorenz cipher, the German teleprinter cipher, called "Tunny" at Bletchley Park, led to successful attack methods. It was to exploit those methods that Colossus, the first digital programmable electronic computer, was designed and built.

Tiltman's parents were from Scotland, though he was born in London. He joined the British Army in 1914, and saw service at the front during World War I with the King's Own Scottish Borderers. He was wounded in France, and won the Military Cross for bravery. He was seconded to MI1 shortly before it merged with Room 40.

From 1921 1929, he was a cryptanalyst with the Indian Army at Army Headquarters, Simla. They were reading Russian diplomatic cypher traffic from Moscow to Kabul, Afghanistan, and Tashkent, Turkestan. In the small section of five or less he was involved in all aspects, directing interception and traffic analysis as well as working on cyphers; he said he was exceptionally lucky to have this experience in other branches of Signals Intelligence.

After a decade as a War Office civilian at GC&CS, the interwar cryptographic organization, Tiltman was recalled to active service. His experience enabled him to assist in many areas of endeavor at GC&CS. He was considered one of Bletchley Parks finest cryptanalysts on non - machine systems.

Tiltman was an early and persistent advocate of British cooperation with the United States in cryptology. His advocacy helped achieve smooth relations during World War II.

In 1944, he was promoted to Brigadier and appointed Deputy Director of GC&CS. He continued in 1946, as Assistant Director of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), successor to GC&CS. Tiltman became Senior GCHQ Liaison Officer at the Army Security Agency in 1949. He retired as a Brigadier.

In 1951 Tiltman met William Friedman, one of the leading scholars involved in the attempt to decipher the mysterious Voynich manuscript. Tiltman undertook an analysis of the ancient manuscript himself, and then in the 1970s he assigned an NSA cryptanalyst named Mary D'Imperio to take over the Voynich cryptanalysis, when Friedman's health began to fail. D'Imperio's work became the book The Voynich Manuscript: An Elegant Enigma, and is now considered one of the standard reference works on the Voynich Manuscript. Tiltman wrote the Foreword to this book.

After reaching normal retirement age, Tiltman was retained by GCHQ from 1954 1964. From 1964 1980 he was a consultant and researcher at the National Security Agency, spending in all 60 years at the cutting edge of SIGINT.

Tiltman made the transition from the manual ciphers of the early 20th century to the sophisticated machine systems of the latter half of the century; he was one of a very few who were able to do so. "The Brig" as he was affectionately known in both countries, compiled a lengthy record of high achievement.

On 1 September 2004, Tiltman was inducted into the "NSA Hall of Honor", the first non - US citizen to be recognized in that way. The NSA commented, "His efforts at training and his attention to all the many facets that make up cryptology inspired the best in all who encountered him."