<Back to Index>

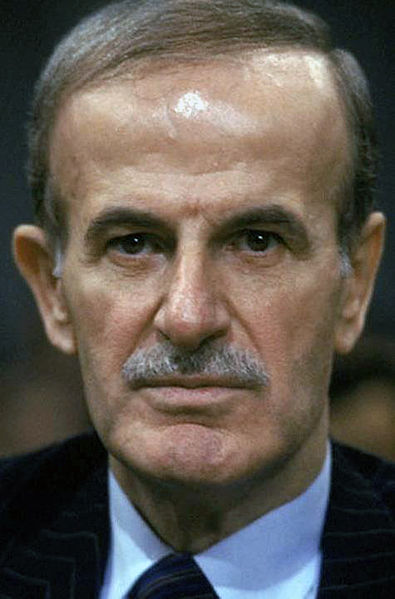

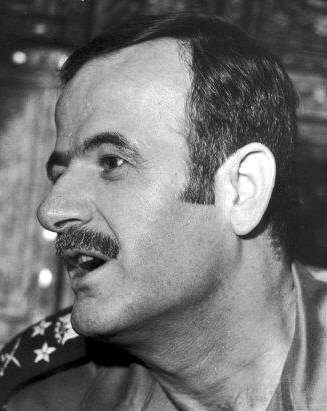

- President of Syria Hafez al-Assad, 1930

PAGE SPONSOR

Hafez al-Assad (Arabic: حافظ الأسد; 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was a Syrian statesman, politician and general who served as Prime Minister of Syria between 1970 and 1971 and then President between 1971 and 2000. He also served as Secretary of the Syrian Regional Command of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, Secretary General of the National Command of the Ba'ath Party from 1970 to 2000 and Minister of Defense from 1966 to 1972. Politically, Assad was a Ba'athist and adhered to an ideology of Arab nationalism and Arab socialism. Under his administration the Syrian Arab Republic saw increased stability, with a program of secularization and industrialization designed to modernize and strengthen the country as a regional power.

Born to a poor Alawite family, Assad joined the Syrian wing of the Ba'ath Party in 1946 as a student activist. In 1952 he entered the Homs Military Academy and graduated three years later as a pilot. Between 1959 and 1961 during Syria's short lived union with Egypt in the United Arab Republic, Assad was exiled to Egypt, where he and other military officers formed a committee to resurrect the fortunes of the Syrian Ba'ath Party. After the Ba'athists took power in 1963, Assad became commander of the air force. In 1966, after taking part in a coup that overthrew the civilian leadership of the party and sent its founders into exile, he became Minister of Defense. During Assad’s ministry, Syria lost the Golan Heights to Israel in the Six Day War in 1967, a blow that shaped much of his future political career. Assad then engaged in a protracted power struggle with Salah al-Jadid, chief of staff of the armed forces, Assad's political mentor, and effective leader of Syria until November 1970, when Assad seized control and arrested Jadid and other members of the government. He became prime minister and in 1971 was elected president.

In 1973 Assad changed Syria's Constitution in order to guarantee equal status for women and enable non Muslims to become president; the latter change was reverted under pressure from the Muslim Brotherhood. Assad set about building up the Syrian military with Soviet aid and gained popular support through public works funded by Arab donors and international lending institutions. Political dissenters were eliminated by arrest, torture and execution, and when the Muslim Brotherhood mounted a rebellion in Hama in 1982, Assad suppressed it and killed 10,000 – 25,000 people. Assad tried to establish Syria as a leader of the Arab world. A new alliance with Egypt culminated in the Yom Kippur War against Israel in October 1973, but Egypt's unexpected cessation of hostilities exposed Syria to military defeat. In 1976, with Lebanon racked by the civil war, Assad dispatched several divisions to that country and secured their permanent presence as part of a peacekeeping force sponsored by the Arab League. After Israel's invasion and occupation of southern Lebanon in 1982 – 1985, Assad reasserted control of the country, eventually compelling Lebanese Christians to accept constitutional changes granting Muslims equal representation in government. Assad also aided Palestinian and Lebanese resistance groups based in Lebanon and Syria, supported Iran in its war against Iraq (1980 – 1988), and joined the U.S. led alliance against Iraq in the Gulf War of 1990 – 1991. Assad sought to establish peaceful relations with Israel in the mid 1990s, but his repeated call for the return of the Golan Heights stalled the talks. He died of a heart attack, and was succeeded as dictator by his son, Bashar al-Assad, who, despite changing times, continued to view Syria as a family fiefdom.

Assad was a controversial and highly divisive world figure. He was lauded as a champion of secularism, women's rights and Syrian nationalism by his supporters, but his critics accused him of being a dictator who constructed a cult of personality and whose authoritarian administration oversaw multiple abuses of human rights both at home and abroad.

Hafez was born on 6 October 1930 in Qardaha to an Alawite family. His parents were Na'sa and Ali Sulayman. Hafez was Ali's ninth son and the fourth son from his second marriage. Sulayman married twice, had eleven children and was known for his strength and shooting abilities, so locals nicknamed him Wahhish (a wild beast - his grandson became known by the same cognomen, but for his brutality, rather than his strength). By the 1920s, he became well respected among the locals and like many others, he opposed the French occupation initially. Nevertheless, Ali Sulayman later cooperated with the French administration and was appointed to an official post. In 1936, he was one of 80 Alawi notables who signed a letter addressed to the French Prime Minister stating that "Alawi people rejected attachment to Syria and wished to stay under French protection." For his accomplishments, he was called al-Assad (a lion) by the locals. He made his nickname a surname in 1927.

Alawites at first opposed the united Syrian state as they thought that their status as a religious minority would put them in danger. Hafez's father shared this opinion. As the French left Syria, many Syrians became suspicious of Alawites for their alignment with France. At the time, Hafez left his Alawite village and started education in Sunni dominant Latakia when he was nine. He was the first member of the Alawite community to attend a high school. In Latakia, Assad faced the anti - Alawite prejudice of the Sunnis. However, he was an excellent student, winning a few prizes when he was around fourteen. Assad lived in a poor, predominantly Alawite part of Latakia. In order to fit in, he approached the political parties that welcomed Alawites. These parties, that also supported secularism, were the Syrian Communist Party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party and the Ba'ath Party; Assad joined the last in 1946, while some of his friends were also members of the Nationalist Party. The Ba'ath Party, also called the Renaissance Party, was a Pan Arabic socialist party.

Assad was an asset to the party, organizing Ba'ath students' cells and carrying its message to the poor sections of Latakia and Alawite villages. He was opposed by the Muslim Brotherhood, which was allied to wealthy conservative Muslim families. The high school catered for the children of both rich and poor families. Assad was joined by the poor, anti - establishment Sunni Muslim youth from the Ba'ath Party in his confrontations with the children of the rich Brotherhood members. He made many Sunni friends, some of whom later became his political allies. While he was still a teenager, Hafez became invaluable to the Ba'ath Party. He was an organizer and recruiter, the head of his school's student affair committee between 1949 and 1951, and later President of the Union of Syrian Students. During his political activity in school, he met many men that would serve him while he was dictator.

After his graduation from high school, Assad wanted to be a medical doctor but his father could not pay for his study at the Jesuit University of St. Joseph in Beirut. Instead, in 1950 he decided to join the Syrian Armed Forces. Assad entered the Military Academy in Homs, which offered free food, lodging and a stipend that suited him. He wanted to fly, and entered the flying school in Aleppo in 1950. Assad graduated in 1955, after which he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Syrian Air Force. Upon his graduation from the flying school, he won a trophy for the best aviator and shortly afterwards was assigned to the Mezze air base near Damascus. While he was a lieutenant in his early 20s, he married Aniseh Makhlouf, a distant relative of a powerful family.

In 1954, the military split in a revolt against Adib Shishakli. Hashim al-Atassi, head of the National Bloc and briefly the president after Sami al-Hinnawi's coup, returned as president; Syria was again under the civilian rule. After1955, Atassi's hold on the country was increasingly shaky. At the 1955 election, Atassi was replaced by Shukri al-Quwatli, who had been president before Syria's independence from France. At the time, the Ba'ath Party started to get close to the Communist Party; not because of shared ideology, but shared opposition towards the west. While at the Academy, Assad met Mustafa Tlass, his future Minister of Defense. When in 1956 Gamal Abdel Nasser took control of the Suez Canal, Syria feared retaliation from the United Kingdom and Hafez flew in an air defense mission. In 1955, Assad was sent to Egypt for a further six months training. He was among the Syrian pilots who were sent to fly to Cairo to show Syria's commitment to Egypt, which was threatened by Israel and members of the Baghdad Pact, which included Iraq and Turkey. After he finished a course in Egypt the following year, Assad returned to a small air base near Damascus. In that year, during the Suez Crisis, Assad flew a reconnaissance mission over northern and eastern Syria. In 1957 Assad became squadron commander and was sent the the Soviet Union for training to fly the MiG-17. He spent ten months in the Soviet Union, during which he fathered a daughter who died as an infant while he was abroad.

In 1958, Syria and Egypt formed the United Arab Republic (UAR), separating themselves from Iraq, Iran, Pakistan and Turkey, which were aligned to the United Kingdom. This pact led to the rejection of Communist influence in favor of Egyptian control over Syria. All Syrian political parties, including the Ba'ath Party, were dissolved. Senior officers, especially those who supported the Communists, were dismissed from the Syrian Armed Forces. Assad however remained in the army and rose quickly through its ranks. After attaining the rank of captain, Assad was transferred to Egypt where he continued his military education, studying together with his Egyptian colleague Hosni Mubarak, the future president - dictator of Egypt.

Assad was not content with a professional military career and regarded it as an avenue into politics. After the UAR was created, Michel Aflaq, leader of the Ba'ath Party, was forced by Nasser to dissolved the Ba'ath Party, which he did. During the existence of the UAR the Ba'ath Party suffered a serious crisis, for which several of its members — mostly young — blamed Aflaq. In order to resurrect the Syrian Regional Branch of the Ba'ath Party, Muhammad Umran, Salah Jadid and Assad, among others, established the Military Committee. In the period 1957 – 58 Assad acquired a dominant position in the party and did not despair because of his transfer to Egypt. He was hard working, skillful and highly ambitious, and became one of the leaders of the Military Committee, which was established in Egypt with aim of rescuing the UAR from dissolution. However, after Syria left the UAR in September 1961, Assad and other Ba'athist officers were removed from the military by the new regime in Damascus, and Assad given a minor clerical position in the Ministry of Transport.

Assad played a minor role in the failed 1962 military coup, for which he was jailed in Lebanon and was later repatriated. In the same year, Aflaq convened the Fifth Congress of the Ba'ath Party, where he was reelected as the National Command's Secretary General and ordered the re-establishment of the party's Syrian Regional Branch. At the Congress, the Military Committee through Umran established contacts with Aflaq and the Ba'athist leadership. The Military Committee asked for permission to seize power through forceful means; Aflaq consented to the conspiracy. After the success of the Iraqi coup d'état, led by the Ba'ath Party's Iraqi Regional Branch, the Military Committee hastily convened to launch a Ba'athist military coup in March 1963 against President Nazim al-Kudsi, which Assad helped to plan and in which he played a major role. The coup was planned for the 7 March, but was postponed until the next day, which Assad had announced to the other units. During the coup Assad led a small group to capture the Dumayr air base, 40 kilometers (25 mi) northeast of Damascus. His group was the only one to see resistance. Some of the airplanes at the base were ordered to bomb the conspirators, and because of this, Assad hastened to reach the base before dawn. It took longer than planned to get the 70th Armored Brigade to surrender, because of which Assad arrived in broad daylight. He threatened the base commander that he would shell them if they did not surrender; the base commander initiated negotiations with Assad and eventually surrendered. Assad claimed that the base was able to defend itself from his forces. After the coup was over, Assad was promoted to major and subsequently to lieutenant colonel, and by the end of 1963 he was put in charge of the Syrian Air Force. By the end of 1964 he was named commander of the Syrian Air Force with a rank of major general. Even though still a leader of the Ba'ath Party, the Military Committee was seizing power from the civilian wing of the party under Aflaq.

As head of the Air Force, Assad gave special privileges to its officers, appointed his confidants to senior and sensitive positions, and established an efficient intelligence network. Thus the Air Force Intelligence, under command of Muhammad al-Khuli, became independent of Syria's other intelligence organizations and was given assignments beyond the Air Force. Assad prepared himself to take an active role in the power struggles that lay ahead. Between 1963 and 1970, he demonstrated ambition, single - mindedness, patience, caution, coolness and manipulativeness. In the first stage of the power struggle, Assad remained the junior partner in the leading Alawite Triumvirate of the Military Committee, along with generals Umran and Jadid. However, when Umran, the senior member of the Military Committee, changed his allegiance to Aflaq, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, Munif al-Razzaz and the civilian leadership in 1965, the power struggle which had lasted since taking power, the remaining members of the Military Committee launched the 1966 Syrian coup d'état and overthrew the civilian Ba'athist leadership. This coup led to a permanent schism within the Ba'ath movement, the advent of neo - Ba'athism and the establishment of two centers for the international Ba'athist movement — one Iraqi dominated, another Syrian dominated.

After the coup, Assad was appointed Minister of Defense, and became the second most influential person in the neo - Ba'athist regime. While holding this ministry, Assad prepared for ousting Salah Jadid, the country's de facto leader. Assad turned the military into his power base and employed brutal force, political manipulation, and ideological and strategic arguments to undermine Jadid's position and gain supremacy. In 1970 Syria supported Palestinian guerrillas in their war against Jordan, known as the Black September, and Jadid sent an armored force to aid the Palestinians. Assad opposed Syria's intervention and refused to send the Air Force in support, which allowed the Royal Jordanian Air Force to rout the Syrian forces unopposed and turned the invasion into a disaster. Assad used Syria's defeat in the War of Attrition against Israel between 1967 and 1970 and the Black September affair to discredit Jadid and extend his own control over the Armed Forces and the Ba'ath Party. In two military coups in February 1969 and November 1970, Assad evicted and arrested Jadid and his senior followers in the government, and assumed unchallenged control over Syria. Assad expanded his control over the military and expanded the network of the security organizations in order to gain support from both Sunni and non Sunni Syrians. Assad successfully became a popular leader deriving his authority from the people. His wish for power was also motivated by his nationalist views; Assad believed in the creation of Greater Syria by creating a political and military alliance with Lebanon, Jordan and the Palestinians.

In 1971, while Prime Minister, Assad embarked upon a "corrective movement" at the Eleventh National Congress of the Ba'ath Party. There was to be a general revision of national policy, which also included the introduction of measures to consolidate his rule. His Ba'athist predecessors had restricted control of Islam in public life and government. Because the Constitution allowed only Sunnis to became president, Assad, unlike Jadid, presented himself as a pious Muslim. In order to gain support from the ulama — the educated Muslim class — he prayed in Sunni mosques, even though he was an Alawite. Among the measures he introduced were the raising in rank of some 2,000 religious functionaries and the appointment of an alim as minister of religious functionaries and construction of mosques. He appointed a little known Sunni Muslim teacher, Ahmad al-Khatib, as Head of State in order to satisfy the Sunni majority. Assad also appointed Sunnis to senior positions in the government, the military and the party. All of Assad's prime ministers, defense ministers and foreign ministers and a majority of his cabinet were Sunnis. In the early 1970s, he was verified as an authentic Muslim by the Sunni Mufti of Damascus and made the Hajj — the pilgrimage to Mecca. In his speeches, he often used Muslim terms like jihad (a holy war) and shahada (martyrdom) when referring to fighting Israel.

After gaining enough power, Assad needed to become leader of the Ba'ath Party, so he ordered the arrests and discharge of the incumbent party leaders, replacing them by his own supporters in the Ba'ath Regional Command. They promptly elected him as secretary general of the party's Syrian branch, confirming his status as the country's de facto leader. The Regional Command also appointed a new People's Assembly, which in 1971 nominated him for the presidency as the only candidate. On 22 February 1971, Assad resigned from the Air Force and was subsequently endorsed as president with 99.6% of the vote at the referendum held on 12 March 1971. He also returned the old Islamic Presidential Oath of Office. While continuing to use the Ba'ath Party, its ideology and its expanding apparatus as instruments of his rule and policies, Assad established a powerful, centralized presidential system - dictatorship with absolute authority for the first time in Syria's modern history.

Robert D. Kaplan has compared Hafez al-Assad's coming to power to "an untouchable becoming maharajah in India or a Jew becoming tsar in Russia — an unprecedented development shocking to the Sunni majority population which had monopolized power for so many centuries." In 1973, a new constitution was adopted that omitted the old requirement that the religion of the state be Islam and replaced it with the statement that the religion of the republic's president is Islam. Protests erupted when this was known. In 1974, in order to satisfy this constitutional requirement, Musa Sadr, a leader of the Twelvers of Lebanon and founder of the Amal Movement who had earlier sought to unite Lebanese Alawis and Shias under the Supreme Islamic Shiite Council without success, issued a fatwa stating that Alawis were a community of Twelver Shia Muslims.

Assad wanted his regime to appear democratic. The People's Assembly and his cabinet consisted of several nationalist and socialist parties under the umbrella of the National Progressive Front, which was led by the Ba'ath Party. Half of his cabinet were representatives of peasants and workers, and a number of popular organizations of peasants, workers, women and students were established in order to participate in the ``decision making" process. As he gained support from the peasantry, workers, the youth, the military and the Alawite community, Assad wanted to destroy his remaining opposition. He tried to present himself as a leader - reformer, a state builder and nation builder by developing and modernizing the country's socio - economic infrastructure, achieving political stability, economic opportunities and ideological consensus. As he wanted to create ideological consensus and national unity, Assad advocated a dynamic regional policy while opposing Zionism and imperialism.

For his entire tenure as Syria's dictator, Assad ruled under the terms of a state of emergency dating to 1963. Under the provisions of the emergency law, the press was limited to three Ba'ath controlled newspapers and political dissidents were often tried in security courts that operated outside the regular judicial system. Human Rights Watch estimated that a minimum of 17,000 people had disappeared without the formalities of a trial. Every seven years, Assad was nominated as the sole candidate for president by the People's Council, and confirmed as dictator by a ``referendum". He was re-elected four times, each time gaining over 99 percent of the vote — including three times in which he received ``unanimous support", according to official figures.

However, Assad's domestic policy encountered serious difficulties and setbacks, and produced new problems and ill feelings particularly among the Sunni urban classes; the orthodox section of these classes also continued to oppose Assad's regime for being a military sectarian dictatorship. As it happened, the continued Muslim opposition to his regime as well as the shortcomings of his socio - economic policies further enforced Assad's initial tendency to give prime attention to Syria's regional affairs, namely intra - Arab and anti - Israeli policies. This tendency did not stem only for Assad's expectations to score quick and spectacular gains in his foreign policies at a time when the crucial socio - economic issues of Syria required long term and painstaking efforts without promise of immediate positive results. Furthermore, in addition to his strong ambition to turn Syria into a regional power and himself become a pan Arab leader, Assad calculated that working for Arab unity and stepping up the struggle against Israel were likely to strengthen his legitimacy and leadership among the various sections of the Syrian population.

Assad's first foreign policy actions after he came to power were to join the newly established Federation of Arab Republics along with Egypt, Libya and later Sudan, and to sign a military pact with Egypt. Assad gave a high priority to quick building of a strong military, while preparing it for a confrontation with Israel, both for offensive and defensive purposes and to enable him to politically negotiate the return of the Golan Heights from a position of military strength. He allocated up to 70 percent of the annual budget to the military build up and received large quantities of modern arms from the Soviet Union.

On 31 January 1973, Assad implemented the new Constitution which led to a crisis in the country. Unlike any other previous constitution, this one did not have an article affirming that the president of Syria must be a Muslim. The fierce demonstrations broke out in Hama, Homs and Aleppo. They were organized by the Muslim Brotherhood and the ulama. They labeled Assad as the "enemy of Allah", even calling for a jihad (a holy war) against his rule. Assad responded with repression, arresting some 40 Sunni officers who were accused for plotting. Nevertheless, Assad added the concerned article into the Constitution to please the Sunnis, but he also stated that he "rejects every uncultured interpretation of Islam that lays bare an odious narrow - mindedness and loathsome bigotry".

Once Assad had prepared his army, he was ready to join Anwar al-Sadat's Egypt in the Yom Kippur War in October 1973. The Syrian military was badly defeated in the war, but while Sadat signed unilateral agreements with Israel, Assad emerged from the war as a national hero in Syria as well as parts of the Arab world. This was due not only to his bold decision to go to war against Israel, but Syria's subsequently carrying out single - handedly a war of attrition against the Israeli Defense Forces in spring 1974. Assad's skill as a cool, proud, tough and shrewd negotiator in the post war period enabled him to gain not only the town of Kuneitra but also respect and admiration of many Arabs in Syria and elsewhere. Many of his followers now regarded Assad as the new pan Arab leader, and a worthy successor of Gamal Nasser.

While promoting his personality cult as a historical leader in the model of Nasser and Salah ad-Din, Assad had indeed regarded his supreme twofold goal to be Arab unity and an uncompromising struggle against Israel. The latter goal, with its military, political, economic and cultural ramifications, did not only stem for Assad's need for legitimacy as an Alawite ruler of Syria who wished to present himself as a genuine Arab and Muslim leader. Assad had apparently been convinced that Israel presented a severe threat to the integrity of the Arab nation from Nile to Euphrates, and that it was, therefore, his historic mission to defend Arabdom. He regarded the confrontation with Israel as a zero sum struggle, and as a good strategist who understood power politics, he had sought to counterbalance Israeli military might with an all - Arab political - military alliance. However, since Egypt under Sadat's leadership defected from this alliance following the 1973 war, Assad endeavored during the middle late 1970s to establish an alternative all - Arab alliance with Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). However, facing grave difficulties to reach an understanding with Ba'athist Iraq, as he didn't want to play a secondary role in an Iraqi - Syrian union, Assad returned to his country's historic goal, to create under his leadership a Greater Syria union or alliance with Jordan, Lebanon and the PLO. As it happened, during the second half of the 1970s, Assad managed to significantly advance, political, military and economic cooperation with Jordan; to extend his control over large parts of Lebanon while intervening in the Lebanese Civil War, and for a while, also to sustain his strategic alliance with the PLO.

Parallel to his regional accomplishments, Assad also had significant gains in his relations with the superpowers. In 1974, he embarrassed the Soviet Union by negotiating with the United States regarding the military disengagement on the Golan Heights, and in 1976 he ignored Soviet pressure and requests to refrain from invading Lebanon and subsequently to refrain from attacking the PLO and the Lebanese radical forces. Simultaneously, Assad renewed and markedly improved his relations with the United States, and made both presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter his great admirers.

However, neither Assad's international and regional achievements nor his domestic gains lasted long, and soon showed sign of collapse, partly owing to his miscalculation and partly because of changing circumstances. The major source of his initial successes, his regional politics, turned out to be main causes of his severe setbacks. Primarily, Assad's direct intervention in Lebanon proved to be a grave miscalculation; within a year or two it turned from an important asset to a grave liability, both regionally and domestically. Thus Assad's maneuvers among the two main rival factions, playing one against other, served to alienate both. The PLO, experiencing Assad's blows in 1976, distanced itself from him and consolidated its autonomous infrastructure in southern Lebanon, paradoxically with Israel's indirect assistance, as Israel firmly objected to the deployment of Syrian troops south of the Sidon - Jazzin "red line".

The Christian Maronites, fearing Syrian domination, in 1978 started a guerrilla warfare against Syrian troops in Beirut and northern Lebanon. Again, Israel's moral support and material aids contributed to foster the Maronites' autonomy and their resistance to Assad's de facto occupation of Lebanon. Furthermore, while Syria drenched its Lebanese quagmire, a newly formed Likud government in Israel, founded in 1977, not only developed political and military relations with the Maronite Lebanese Forces, but also took a further important step, which contributed to undermining Assad's regional position. Israel welcomed Sadat's initiative in November 1977 and signed the Camp David Accords with Egypt and the United States in 1978, to be followed by the Egypt - Israel Peace Treaty in 1979.

Apart from a deep psychological shock, Assad's regional strategic posture also suffered serious blows as Egypt, the most significant Arab country, departed from the all - Arab confrontation against Israel, in effect exposing Syria to a growing Israeli threat. Indeed, apart from a short lived rapprochement with the PLO, Assad became increasingly isolated in the region. His brief unity talks with Iraqi leaders collapsed in mid 1979; and with Iraq's 1980 involvement in the Iraq - Iran War, this second major Arab state also effectively withdrew from the conflict against Israel.

Simultaneously, in 1979, under the impact of the Egypt - Israeli Peace Treaty, and in view of Syria's regional predicament, Jordanian King Husein ibn Talal pulled away from his association with Assad in favor of a closer relationship with Iraq. Finally, Assad's regional strategic position was further damaged as the Carter administration in the United States was geared to abandon its new Syrian oriented policy in favor of the Egypt - Israeli peace process. In this critical situation, with his political skills exhausted, Assad still demonstrated his stamina, obstinacy and single - mindedness.

In 1980, with the first friendship and cooperation agreement with the Soviet Union, Assad continued to develop his new doctrine of Strategic Balance, which he had initiated the previous year. Aiming primarily at confronting Israel single - handedly, this doctrine not only engendered fresh intra - Arab policies, it was also directed toward reconsolidating Assad's domestic front, which, like his regional posture, had suffered setbacks since 1977.

Still more detrimental and threatening was the resurgence and expansion of the Islamic opposition to Assad's regime. Indeed, Assad's initial support of the Christian Maronites and his military actions against the Muslim radicals in Lebanon provoked for the first time a new and unprecedented phase of Muslim resistance to Assad. It took the form of well organized and effective urban guerrilla warfare against government, military and Ba'athist officials and institutions. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Islamic jihad became almost an open rebellion as many Alawite soldiers and officers as well as senior officials were killed, and government and military centers were bombed by the Muslim mujahideen.

Facing a serious menace to his regime and perhaps even to his life, for the first time, Assad lost his coolness and self confidence, and reacted with fury and desperation; reportedly, his health also started to deteriorate during this period. Under his personal orders a ferocious campaign of repression and counter - terror was launched against the Muslim Brotherhood. The campaign of terror started in 1980, when Assad escaped a grenade attack. In response, troops led by his brother Rifaat took revenge by killing 250 inmates at Tadmor Prison in Palmyra. In February 1982, the rebellious city of Hama was bombed by Assad's troops, killing up to 10,000 people, including women and children. It was later described as "the single deadliest act by any Arab government against people in the modern Middle East." Over the next few years, thousands of Muslim Brotherhood followers were arrested and tortured, and many of them were killed or disappeared. At that juncture, Assad finally realized that his previous great efforts to bring about a national unity in Syria, namely to gain legitimacy in the eyes of the Sunni urban population, had totally failed. He was confronted now not only with resistance of the Muslim Brotherhood and their many thousands of followers. Large sections of the urban intelligentsia, professionals and intellectuals, as well as former Ba'ath Party members, also regarded his regime as an illegitimate Alawite sectarian military dictatorship. Later, Assad used the threat of the Muslim Brotherhood to justify his heavy handed rule.

Consequently, Assad became increasingly reliant on the further cultivation of his close constituencies as a support base and a new political community. These consisted of large sections of peasants and workers, salaried middle class and public employees, both Sunnis and non Sunnis alike. Mostly organized in the Ba'ath Party, mass syndicates and trade unions, these sections, like most Alawite minority and Christians, greatly benefited from Assad's policies, and thus depended on him or were ideologically identified with his regime. Another large section of the population that had a strong allegiance to Assad were many of the young Syrians, who for a generation or so were educated or indoctrinated in the notions of the Ba'ath Party as formulated by Assad. These sections of the population not only rendered legitimacy to Assad's regime, but from the time to time were been mobilized by Assad to actively support his policies and curb his domestic enemies. Nonetheless, the hard core of Assad's support base remained the Alawite community, combined with the combat units of the Syrian Armed Forces as well as the wide network of security and intelligence organizations.

Indeed, members of the Alawite community, as well as non Alawites loyal to Assad virtually controlled the huge security, intelligence and military apparatuses of Assad's regime. They manned or commanded about a dozen security and intelligence networks as well as most armored divisions, commandos, and other combat units of the Syrian Armed Forces. In addition to directing a state run repression system against the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, Assad had turned some of his intelligence networks into special apparatuses for terrorism against targets in the Middle East and in Europe. For example, Assad used terrorism and intimidation, in addition to other means, to extend his control over Lebanon: in 1977, his agents assassinated Kamal Jumblatt, the Druze leftist leader, and in 1982 they killed Bachir Gemayel, the newly elected Maronite president, both of whom had struggled against Assad's attempts to dominate Lebanon. By similar tactics, Assad managed to bring the abolition of the 1983 Lebanon-Israel agreement, and through guerrilla warfare carried out by proxy in 1985, Assad indirectly caused the withdrawal of the Israeli Defence Forces from southern Lebanon. Terrorism against Palestinians and Jordanian targets contributed in the mid 1980s to thwart the rapprochement between Jordanian King Hussein and the PLO, as well as to slowing down Jordanian - Israeli political cooperation in the West Bank.

In November 1983, after a serious heart attack kept Assad out of public life, a virtual "war of succession" took place between his brother Rifaat and the army generals. Assad's return from illness brought an end to the discord and he took advantage of the situation to undermine the position of his brother, eventually sending him into exile. His return to supreme power was confirmed at the eight party congress in January 1985.

Israel was the major target of Assad's terrorist and guerrilla operations, not only in Lebanon, but also in Europe. The attempt to bomb an El-Ar airliner in London in April 1986 and the attack on an El-Al jet in Madrid in June 1986 are two examples of his policy. These actions were apparently part of an attrition campaign that Assad had been directing against Israel aimed at damaging its economy, morale and social fabric, as well as weakening its military capacity. However, this campaign of attrition had merely been an auxiliary tactic in Assad's major strategy of strategic balance with Israel. This doctrine of strategic balance or military parity was developed by Assad in the late 1970s, when Syria was largely isolated in the region and exposed to a potential Israeli threat. Assad was then determined to build a powerful military force, in addition to a sound economy and a cohesive national community, in order to single - handedly confront Israel, while exercising his influence over the neighboring Arab countries. The 1982 war with Israel in Lebanon only enhanced Assad's efforts to greatly increase and improve his military. Indeed, with the massive help of the Soviet Union, Assad succeeded in building a huge and modernized military equipped with modern tanks, airplanes and long range ground - to - ground missiles capable of launching chemical warheads into most Israeli centers.

Thus, although he was still far from achieving military superiority over, or a strategic balance with, Israel, Assad nevertheless reached a military parity with the Jewish state in quantitative terms. This military capacity, a major achievement for Assad, enabled him to deter Israel from attacking Syria as well as to cause heavy losses to Israel in case of war. While rendering him an option to regain the Golan Heights, or part of it, by a surprise attack, Assad's enormous military power also enabled him to sustain some of his major political gains in the region and at home. However, Assad was not content with his military buildup, and continued to also employ his unique skills as a first rate strategist and master manipulator in order to advance his prime regional policies, namely to mobilize all - Arab support for his assumed role as a leader of the Arab struggle against Israel, while further isolating Egypt and counterbalancing the growing power of Iraq, Syria's major Arab rivals in the region.

Although Syria had good relations with the Soviet Union, Assad began to turn somewhat more towards the West in late 1980s, having seen the benefits that had accrued to Iraq during its war with Iran. He agreed to join the United States led coalition against Iraq in the Gulf War in 1991. He continued to regard Israel as major regional enemy, however, at the end of 1991 Middle East peace conference insisted on an uncompromising line on "land for peace", demanding Israel's withdrawal from the Golan Heights. The September 1993 Israeli accord with the PLO, which put an end to the intifada (resistance) in the Occupied Territories without giving the Palestinians any substantial gains, represented a setback for Assad, as did the increasingly friendly relationship between Israel and Jordan.

Syria increased importance of the relations with the countries of the European Union, both economically and politically. The EU was Syria's source of financial aid and foreign trade and politically its relations served a counter force to the United States. Assad's Syria also tried to give greater influence to the EU in its region. However, opposition of Israel and the United States prevented EU's influence on the region. Syria's ministers visited number of the EU countries either because of the peace process or other issues, primarily of economic nature. Representatives of Netherlands, France, Portugal and Germany visited Syria. Countries of the European Union were an important source of Syrian trade, for example in 1992 36.8% of Syria's imports were from the EU and 47.9% exports were in the EU.

During the Lebanese Civil War, Syria's relations with France were rather tense, which eventually improved, nevertheless France was still critical of Syria and demanded the reduction of its presence in Lebanon. Later however, the issue was solve with France recognizing Syrian central role in the region as well as Lebanon. In February 1992 French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas visited Damascus in order to discuss the Lebanese question and the peace process. In 1992 Syria's relations with Germany improved. Previously the relations were cold. The improvement occurred when Syria got involved in securing the release of two German hostages in Lebanon which ended the affair of Western hostages in that country. This action of Syria improved its image in the world as well as in Germany. Chanchellor Helmut Kohl thanked Assad for his efforts. German Foreign Minister Hans - Dietrich Genscher visited Syria in September 1992 to discuss the improvement of relations between the two countries.

In the late 1990s, Syria's relations with EU countries continued to improve slowly. They were of economic significance and Syria benefited politically by bolstering its international status. Good relations with the EU allowed Syria some maneuverability regarding Israel.

In the 1980s Syria established a military cooperation with the Soviet Union. Sophisticated Soviet arms as well as military advisors helped the development of the Syrian Army which raised tensions between Israel and Syria. In November 1983 a Soviet delegation arrived in Damascus to discuss opening a Soviet naval base in the Syrian city of Tartus. Nevertheless, Syria and the Soviet Union had some issues in their relationship; Syria's involvement in the Gulf War, in which Syria supported Iran when the Soviet Union was on Iraq's side; the rebellion against Yasser Arafat in al-Fatah in 1983, in which Syria supported the rebels when the Soviets supported Arafat. In order to mend these disagreements between the countries, in 1983 the Syrian Foreign Minister Abdul Halim Khaddam visited Moscow. The Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Gromyko argued that Syria and the Soviet Union must resolve their differences concerning the Palestinian issue as setting aside internal conflicts would allow focusing on the "anti - Imperialist struggle".

During the diplomatic crisis between the United States and Syria which escalated in minor clashes, Syria counted on Soviet help in case the clashes would grow to an outright conflict. The Soviet ambassador in Damascus, Vladimir Yukhin, expressed his country's appreciation "for the firm Syrian position in the face of Imperialism and Zionism." This Soviet attitude did not satisfy Syria completely. Assad's government even considered entering the Warsaw Pact to gain Soviet support and to counter the United States and Israel. Syria and the Soviet Union had also signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation in October 1980. This treaty was focused on general aspects, mainly cultural, technical, military, economic and transport relations. This treaty also included joint action in case any of the countries was attacked and forbade both Syria and the Soviet Union from joining any alliance that was hostile to one of the signatories. Syrian efforts to improve strategic relations with the Soviet Union meant that Syria was not completely satisfied with the current Treaty. Even before the Treaty was signed, the Soviet Union backed the Arab countries, both in the Six Day War of 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of 1973. During the 1982 Lebanon War, the Soviet Union kept a policy of low profile. The Soviets did not send arms nor did they exert pressure to end the conflict. The Syrian Armed Forces and the PLO were militarily defeated. This also damaged Soviet prestige in the region. This Soviet attitude occurred while the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation was in force, so it is understandable why Syria wanted to strengthen its ties with the Soviet Union, especially in the face of an aggressive policy of the United States in Lebanon designed to harm Syria's position there.

The Syrian need for strengthening its ties with the Soviet Union was part of the Assad's policy of strategic balance with Israel. Increased Soviet military support coupled with more Soviet political backing were vital ingredients in Syria's determined effort to match Israeli power. The Soviets, however, had a problem with Syria in 1983 due to a power struggle started by Rif'at al-Assad. In that time Hafez al-Assad was ill and unable to govern the country. The Soviets supported Hafez al-Assad's Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass and were concerned about Rif'at's bid for power. When the Soviet leader Yuri Andropov died, Assad did not attended his funeral, but the Syrian official commentary stated that Andropov supported Soviet - Syrian friendship and that both countries aspired to strengthening bilateral ties in various fields.

Syria's relations with the Soviet Union had been a cornerstone of the Syrian foreign policy for years. The Soviet Union supported Syria politically, militarily and economically, affording Syria a sense of security in the face of external threats, mainly from Israel. However, after 1987 the Soviet Union was unable to support Syria due to internal changes and political turmoil. At the same time this had an impact in the relationship between the states and eventually Syria reduced its support for the Soviet Union as a superpower. Change of the Soviet Middle East policy led to a Syrian change in its relations with Israel which resulted in allowing mass emigration of Jews to Israel and a demand that Syria change its attitude in the conflict with Israel. Alexander Zotov, the Soviet Ambassador, said in November 1989 that Syria's change of foreign policy was necessary, stating that Syria should cease aspiring for strategic balance with Israel and instead settle for "reasonable defensive sufficiency," and that the Soviet - Syrian arms trade would also change. The arms sales were reduced, another reason being the growing debt of Syria to the Soviet Union. This led Syria to find new weapon suppliers, China and North Korea.

Nevertheless, Syria continued to maintain friendly relations with the Soviets. Between 27 and 29 April 1987 Assad visited the Soviet Union along with Defense Minister Tlass and Vice President Khaddam. During the visit, Assad stressed that Jewish emigration to Israel was not only an embarrassment to Syria but that it also served strengthening Israel. Radio Damascus denied the claims that the Soviet Union and Syria were distancing and stated that Assad's visit had renewed the momentum in the relations between the Soviet Union and Syria, consolidating their common view of the Arab - Israeli conflict. Syrian Daily Tishrin stated that after this visit, the relation between the Soviet Union and Syria would be expanded. A few weeks after he returned from Moscow, Assad, in his speech to the National Federation of Syrian Students, said that the Soviet Union remained a firm friend of Syria and the Arabs and no weakening in relations had occurred. Assad stated that even though Mikhail Gorbachev and his government were preoccupied with the internal affairs, they had not neglected foreign affairs, especially those related to their allies. Syria maintained its close economic ties with the Soviet Union. In 1990 44.3% of exports were to the Soviet Union. However, just before the collapse of the Soviet Union the economic, military and political ties between the countries changed. In contrast to previous visiting schedule, in 1991 the Syrian Foreign Minister al-Sharaa visited the Soviet Union only once in April. The Soviet Foreign Ministers Alexander Bessmertnykh and Boris Pankin also visited Syria in May and October. However, those visits were connected only with the American initiative to promote the peace process, accentuating the decline in the status of the Soviet Union in the region.

The collapse of the Soviet Union on 31 December 1991 marked the end of Syria's main source of political and military support for more than two decades. In 1992 the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Russia were dependent on the United States and developed closer ties with Israel which meant that Syria was unable to count on their support. Nevertheless, CIS countries were viewed as limited market and limited source for arms. The absence of high level contracts between Russia and Syria inhibited future development of relations. Russia agreed to fulfill arm sales under previous contracts signed between the Soviet Union and Syria but demanded Syrian payment of $10 - $12 billion worth in debt. Syria refused to do so claiming that Russia was not a successor state to the Soviet Union. However Syria later agreed to pay part of the debt by exporting citrus fruit worth $800 million.

Like other Arab countries, Syria worked on establishing good relations with Muslim countries that were part of the Soviet Union. Syrian Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa visited Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Azerbaijan. However, relations with those states were only limited. Syria, nevertheless, established good relations with another former Soviet state, Armenia. Syria had a large Armenian community.

On 6 July 1999 Assad visited Moscow. The visit was originally planned for April but Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was visiting Moscow at the same time and Assad's visit was postponed. His visit ended with finalizing arm deals worth $2 billion. After the visit both sides stated that they would strengthen trade ties. Assad commented on the growing Russian importance stating that he welcomed Russian strengthening and hoped that Russia's role would be more clearly and more openly expressed. The United States warned Russia not to trade arms to Syria, but Russia stated that it would not yield to American threats in halting cooperation with Syria.

In 1980s a major issue in the relations between the United States and Syria was the situation in Lebanon. In October 1983 the headquarters of the American and French troops of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF), was completely demolished in a suicide attack. Around 200 Americans were killed. The Syrian ambassador in the U.S. denied Syria's involvement in the attack, however, Congress passed an emergency bill cancelling economic aid previously approved for Syria. It was later reported that Syrian support for the attack was massive. Around 800 Shia extremeists were reportedly trained in Syria and Assad's cousin Adnan al-Assad personally supervised the preparations for the attack. Syria decided to resist American and French force, if attacked. At the time Assad's health wasin decline . Syria's Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass said that Syria would launch suicide attacks on the American Sixth Fleet. In December 1983, when American planes pounded Syrian positions in the Beqa'a valley, Syrian air defense systems fought back. Two American planes were destroyed and one pilot was taken a prisoner of war. Just before the attack, Israeli Prime Minister had visited Washington, so Syria linked the American attack with the visit.

In 1990s Syria continued to maintain its good relations with the United States. Nevertheless, unresolved issues between the countries prevented their friendly relationship. One of the issues was allowing Syrian Jews to emigrate, which was allowed in April 1992. The step was welcomed by the George Bush Administration. Syria also showed their commitment to the peace process requesting that the U.S. play a more active role. However, relations between Syria and the United States were still characterized by mutual distrust and differences of opinion on key issues.

One of the issues in the relationship between the two countries was the accusation that Syria was sponsoring terrorist organizations. Despite Syria's efforts to portray itself as having dissociated from these groups, Syria was not removed from the list of countries sponsoring terrorist organizations that appeared in the annual U.S. State Department report on "Patterns of Global Terrorism." The United States believed that Syria continued to help terrorists. In 1991 Syria was one of the suspects in the explosion of the Pan Am plane over Lockerbie in Scotland. Even though the U.S. absolved Syria of responsibility, the U.S. media continued to portray Syria as a suspect. Syria itself denied involvement and protested at not being removed from the "Patterns of Global Terrorism" list. Syria, nevertheless, continued tosponsor a number of organizations that were operating against Israel, including Hezbollah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC).

Relations between Egypt in Syria were renewed in December 1989. In the 1990s Syria had good relations with Egypt. Those relations were of high importance. President of Egypt Mubarak and Assad also had good relations. Syria tried to make Egypt its advocate in front of the United States and Israel, while Egypt tried to convince Syria to go forward with the peace process. Syria also tried to mediate between Egypt and Iran. Those efforts were mainly undertaken by Syrian Foreign Minister al-Sharaa. However, this mediation proved to be futile as there was neither reconciliation nor normalization in relations between Egypt in Iran. Nevertheless, relations between Egypt in Syria were not excellent at either military or economic levels. Those relations were mainly of political nature.

In 1999 relations between Egypt and Syria strained because of the differences over the peace process. Representatives from both countries alluded to this tension on various occasions. During the year, Assad and Egypt's president met only in January 1999 in contrast to their previous practice of meeting every few months during the previous decade. Syria opposed the Egyptian proposal to convene an Arab summit of the countries negotiating with Israel, as Syria was unwilling to place itself in a position where they would be pressured into a dialogue with Yasser Arafat. Later, Syria accused Egypt of seeking to promote negotiations in the Palestinian issue at Syria's expense.

The Islamic revolution in Iran in February 1979 was seen by Assad as an opportunity to further implement his policies. The new regime of Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran promptly abolished Iran's pro-Western link with Egypt, potentially threatened Iraq, and turned Israel from a latent ally into a declared enemy of Iran. Assad thus established a surpising alliance with Iran, whose political and social principles, except those concerning Israel and the United States, were in dramatically contrast to the Ba'athist doctrines of Syria's regime as well as those of the Iraqi government. Furthermore, Assad consistently extended military and diplomatic assistance to Iran in its long and bloody war with Iraq, aiming at securing legitimacy and support for his rule in Syria and his policies in Lebanon, using the Iranian potential threat to manipulate Arab states of the Persian Gulf into continuing their financial and diplomatic support for Syria, weakening and possibly toppling the regime in Baghdad and subsequently employing Iraq and Iran for "strategic depth" and as allies in Syria's confrontation with Israel, thus emerging as leader of the all - Arab struggle against Israel. To be sure, Assad repeated that the war between Iraq and Iran should have never occurred since it was waged against a potential ally of the Arabs, and caused the diversion of the Arabs' attention, resources and efforts from their real enemy, Israel. In other words, according to Assad, most Arab countries had been wrongly led to support Iraq in an unnecessary war against Iran, rather than support Syria in its vital national - historical struggle against Israel.

However, except for securing Arab financial support and verbal commitments, and obtaining large quantities of free and discounted Iranian oil, Assad failed to achieve the main objectives of his Gulf strategy. Moreover, this strategy served to further worsen Syria's regional position. Thus, Assad failed to further isolate Egypt because of its peace with Israel, or weaken or topple the Iraqi leadership because of their war with Iran, or to emerge as leader of an all - Arab coalition vis-à-vis Israel. The growing Iranian threat to Iraq, which Assad indirectly fueled, contributed to bringing Egypt back to the Arab fold and made many Arabs acquiesce with Egypt's peace treaty with Israel; it also served to develop a new alliance between Egypt and Iraq, the two major Arab states, while further isolating Syria in the Arab world; and finally, it helped to consolidate the Iraqi regime and create among its leaders an intense feeling of hatred and revenge towards Assad.

Even though Iraq was ruled by another branch of the Ba'ath Party, Assad's relations with Saddam Hussein were extremely strained. One of the main reasons for the Syria - Iraq tense relations was Saddam's refusal to ally with Syria against Israel, which Assad was unable to forgive to the Iraqi President. When the Iran - Iraq War broke out in 1980 Syria took the part of Iran against Iraq. Iran also succeeded to find an ally, the Kurds in Iraq. The Kurds assisted Iran's offensive at northern Iraq. Massoud Barzani, a Kurdish leader, hoped that Khomeini would give the territory to the Kurds, but Khomeini at the end decided to incorporate it in the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq. Barzani was not satisfied with the decision, so he aligned with Assad's Syria, while Assad was already patronizing Jalal Talabani. Talabani resided in Syria since the 1970s and Assad believed he could benefit from his ties with Syria. Talabani himself stated that he would not forget the support given to him by Assad. This was one of Assad's efforts to expand Syria's zone of influence to Iraq. By receiving Barzani, Assad gained the Kurds on his side, thus decreasing Iran's chances to expand its influence over Iraq. Nevertheless, after the end of the Iran - Iraq War, the Iraqi Kurds still had close relations with Iran.

Assad also participated in the coalition formed to force Iraq from Kuwait in the Gulf War in 1991, however, the Syria - Iraq relations started to improve in 1997 and 1998 when Israel started to develop a strategic partnership with Turkey.

To a large extent, Al-Assad's foreign policy was shaped by Syria's attitude toward Israel. During his presidency, Syria played a major role in the 1973 Arab - Israeli war. The war was presented by the Syrian government as a victory, although by the end of the war the Israeli army had invaded large areas of Syria, and taken up positions 40 km from Damascus. However, through later negotiations Syria regained some territory that had been occupied in 1967. The Syrian government refused to recognize the State of Israel and referred to it as the "Zionist Entity." Only in the mid 1990s did Assad moderate his country's policy towards Israel, as he realized the loss of Soviet support meant a different balance of power in the Middle East. Pressed by the United States, he engaged in negotiations on the Israeli annexed Golan Heights, but these talks failed. Al-Assad believed that what constituted Israel, the West Bank and Gaza, were an integral part of "Southern Syria." Syria also took part in the 1982 Lebanon War.

Assad had cold relations with Jordan. Syria under Assad had a long history of attempts to destabilize King Hussein's regime. Both countries supported opposition forces in order to destabilize each other's regimes. In 1979 when the Islamic uprising started in Syria, Jordan supported the Muslim Brotherhood. Assad accused King Hussein of supporting them, and after crushing the Islamists, Assad sent Syrian troops on the border with Jordan. In December 1980 some Arab newspapers reported that Syrian jets attacked Muslim Brotherhood's bases located in Jordan. Saudi Arabia mediated in order to calm the situation. A significant factor for Syria's hostility towards Jordan was its good relationship with Syria's rival Iraq. During the Iraq - Iran War in the 1980s, Syria and Jordan supported different sides. Not even the threat of war with Syria did prevented King Hussein to support Iraq; however, the rest of the Arab States of the Persian Gulf did the same. In October 1998 Syria's Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass stated that "there is no such country as Jordan. Jordan was merely south Syria". Nevertheless, when King Hussein died in February 1999, Assad attended his funeral, after which relations between Syria and Jordan started to improve. Hussein's successor, King Abdullah visited Syria in April 1999 which was rated as a "turning point" in the relationship between the two countries.

Syria deployed troops to Lebanon in 1976 during the Lebanese Civil War, as part of the Arab Deterrent Force. Military intervention had been requested by the Lebanese President Suleiman Frangieh, as Lebanese Christian fears had been greatly exacerbated by the Damour massacre. Syria responded by ending its prior affiliation with the Palestinian Rejectionist Front and began supporting the Maronite dominated government. It is alleged that the Syrian presence in Lebanon began earlier with its involvement in as-Saiqa, a Palestinian militia composed primarily of Syrians. The Arab League agreed to send a peacekeeping force mostly composed of Syrian troops. The initial goal was to save the Lebanese government from being overrun by the Left and the Palestinian militancy. Critics allege that this turned into an occupation by 1982, which is not disputed within the Lebanese community. The Syrian presence ended in 2005, due to UN resolution 1559, after the Rafiq Hariri assassination and the March 14 protests.

Throughout 1970 Gaddafi and Egypt's President Sadat were involved in the negotiations about the union between Egypt and Libya. Assad, at the time Lieutenant General, expanded the negotiations on Syria in September 1970 when in Libya in order to revive the "Steadfastness Front", established by the radical Arab countries. In April 1971 the three leaders announced the Federation of Arab Republics between the three countries. When the Yom Kippur War started in 1973, Libya opposed its direction and criticized Egypt and Syria for restricted objectives. Libya was also unhappy with being sidelined. Nevertheless, Libya supported the war and had stationed troops in Egypt before the war began. When the Arab countries lost the war and ceasefire negotiations started, Muammar Gaddafi was infuriated. After the war Gaddafi criticized Sadat and Assad for not consulting him before the war. Egypt's marginalization of Libya and acceptance of the Camp David accords led Libya to adopt a more hostile stance against Israel. Eventually, Libya started to maintain good relations with Syria who also opposed Egypt after the Camp David accords.

Gaddafi tried to expand the Arab unity towards the west. In 1974 he proposed a union to Tunisia, but the proposal was immediately repudiated by the Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba and after several incidents between Tunisia and Libya, the countries broke diplomatic relations. After failing to form a union with Tunisa and Egypt, Gaddafi again turned to Assad. In September 1980 Assad agreed to enter another union with Libya. This union occurred when both countries were diplomatically isolated. As part of the agreement, Libya paid the Syrian debt of US$ 1 billion owned to the Soviet Union for weapons. Ironically, this union with Syria confounded Gaddafi's pan Arab ambitions. In the same month when the union was formed, the war between Iraq and Iran broke out and Syria and Libya were the only Arab states to support Iran.

In 1992, during the crisis between Libya and the West, after the West accused Libya for involvement in terrorist operations, and despite the long lasting friendship between Assad and Gaddafi, Syria refrained from any substantive support for Libya; its support was only verbal. In order to get more support from Syria, Gaddafi sent a delegation to Damascus in January headed by Colonel Mustafa al-Kharubi. In March, while Assad was visiting Egypt, he met with the Libyan representative to the Arab League. Later in the same month, Abu Zayd 'Umar Durd, secretary of the Libyan General People's Committees, also visited Damascus. However, Syria was unable to do anything more but to denounce the UN's Security Council resolution imposing sanctions on Libya, condemning it as unjustified provocation, especially in view of what Syria depicted as a double standard applied by the international community toward Libya, on the one hand, and Israel, on the other. Once the sanctions were in force on 15 April, Syria announced that it would violate the embargo and maintain areal contacts with Libya, however, American pressure and Syria's technical inability to send flights to Libya caused them to reverse the decision.

The hostile attitude to Israel meant vocal support for the Palestinians, but that did not translate into friendly relations with their organizations. In the 1970s, Al-Assad conducted military operations against Palestinian camps in Lebanon, including involvement in the Tel al-Zaatar massacre, which drew strong criticism for his regime in the Arab world. Hafez al-Assad was always wary of independent Palestinian organizations, as he aimed to bring the Palestinian issue under Syrian control in order to use it as a political tool. He soon developed an implacable animosity towards Yasser Arafat's PLO, against which Syria fought bloody battles in Lebanon. As Arafat moved the PLO in a more moderate direction, seeking compromise with Israel, al-Assad feared regional isolation, and he resented the PLO's underground operations in Palestinian refugee camps in Syria. Arafat was depicted by Syria as a rogue madman and an American marionette, and after accusing him of supporting the Hama revolt, al-Assad backed the 1983 Abu Musa rebellion inside Arafat's Fatah movement. A number of unsuccessful Syrian attempts to kill Arafat were also made.

The relations between Turkey and Syria during Assad's rule were tense. Even though the problem of the Hatay Province existed in the early 1970s, bigger issues to the Syria's relations with Turkey were water supply and Syria's support to the Kurdistan Workers' Party and the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA). Another problem in their bilateral relations was the fact that Turkey was part of NATO, while Syria was allied to the Soviet Union; nevertheless, the Cold War was a guarantor to the status quo. After the end of the Cold War, the issue of Hatay Province came to the surface. Hatay Province was handed over to Turkey by France, which was, at the time, a mandatory power in Syria.

Assad offered help to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). Assad not only sheltered, trained and equipped Lebanon's PKK, he also enabled the organization to receive training in Beka'a' Valley in Lebanon. Abdullah Öcalan, one of the founders of the PKK, openly used his villa in Damascus as a base for operations. Turkey threatened to cut of all water supplies to Syria. However, whenever the Turkish Prime Minister or President sent a formal letter to the Syrian leadership requesting a stop to its support to the PKK, Assad would ignore them. Turkey at the time was not able to attack Syria due to low military capacity near the Syrian border and the advise of European NATO members to stay away from getting involved in the Middle East conflicts in order to avoid escalation of the conflict and involvement of the Warsaw Pact states, as Syria had good relations with the Soviet Union. However, after the end of the Cold War, Turkish military concentration on the Syrian border increased. Later, during the summer of 1998, Turkey threatened with military action because of Syrian aid to Öcalan, and in October they gave Syria an ultimatum. Assad was aware of the possible consequences of Syria's continuing support to the PKK. Not only was Turkey powerful militarily, but also Syria did not have the support of the Soviet Union any more. The Russian Federation was not willing to help, neither was capable to take strong meassures against Turkey. Facing a real threat of military confronation with Turkey, Syria signed the Adana Memorandum in October 1998. This agreement designeted the PKK as a terrorist organization and required Syria to evict the PKK from its territory. After the PKK was dissolved in Syria, Turkish - Syrian relations improved considerably in the political domain. However, major issues, such as the waters of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and the Hatay Province, remained unresolved.

Assad labeled his domestic reforms as a corrective movement, making great efforts and achieving substantial results, particularly during the first six - seven years of his rule, in various economic and social fields. Assad made great efforts to modernize the agricultural and the industrial sectors of the Syrian economy. One of the most successful of Assad's achievements was the completion of the Tabqa Dam on the Euphrates River in 1974. Tabqa Dam is one of the biggest dams in the world, with a huge water reservoir named Lake Assad. Lake Assad greatly increased the irrigation of arable lands, provided electric power to many regions of the country, and fostered industrial as well as technical development in Syria. Parallel to his efforts to advance agriculture and develop modern industry, the conditions of many peasants and workers were noticeably improved in terms of financial income and social security as well as health and educational services. The urban middle classes, merchants, artisans, shopkeepers, and the like, which had been hurt by the Jadid regime's policy were given new economic opportuinites by Assad.

By 1977, it become clear that Assad's state building and nation building reforms, despite certain achievements, had largely failed to reach their goals. Here again, the causes for these failures were partly related to Assad's miscalculations or mistakes, and partly to factors that he was unable to control or change within a short period of time. Thus, the chronic socio - economic difficulties of Syria mostly persisted, while new ones were created. The major problems were mismanagement, inefficiency and corruption in the government bureaucracy as well as in the public and private economic sectors; illiteracy and low level education, particularly in rural areas, and an increasing brain drain of professionals; and a growing trade deficit and inflation, high cost of living, and shortages in consumer goods and the like. Syria's involvement in Lebanon since 1976 with the resulting financial burden contributed not only to worsen economic problems, but also fostered the spread of corruption and black - marketing to high levels. The emerging new class of enterpreneurs and brokers became involved with senior military officers, among which was Assad's brother Rifaat, in smuggling contraband goods from Lebanon, thus affecting government revenues and spreading bribery among senior governmental officials.

In the early 1980s Syria had serious economic difficulties - food shortages and illegal economy. In mid 1984 the food crisis was so severe that the press was full of complaints. Assad's government looked for a decisive solution. They argued that food shortages can be avioided with application of careful and sophisticated economic planning. In August, however, the food crisis with severe shortages continued despite the government's measures. Syria lacked sugar, bread, flour, wood, iron and construction equipment. The resuls were soaring prices, long queues and rampant black marketing. Smuggling of goods from Lebanon was a constant occurrence since Syria's invasion of that country in 1976. Assad's government made a great effort to combat the smuggling, but saw difficulties due to the involvement of Assad's brother Rif'at in the illegal business. In July 1984 Syria formed a special anti - smuggling squad to control the Lebanon - Syria border. The maesures were effective. The Defense Deatachment commanded by Rif'at al-Assad played a leading role in the smuggling business, importing $400,000 worth of goods a day. The government's anti - smuggling squads seized $3.8 million worth of goods only in the first week.

In the early 1990s, the Syrian economy continued to grow. Syrian exports were increased, the balance of trade continued to improve and inflation remained moderate 15% - 18%. Along with investment, Syrian economy also increased in activity. In May 1991 Assad's government made a decision to liberalize the Syrian economy which proved to be beneficial as it stimulated domestic and foreign private investment. Most of the foreign investors were Arab states of the Persian Gulf, as the Western countries still had issues with Syria, both political and economic. In the early 1990s, the Syrian economy saw growth between 5% - 7%. Oil exports also increased. The economic liberalization was a major factor in Syrian economic growth. The Gulf states invested in infrastructure and in development projects. However, Assad's government refused to privatize state owned companies as part of the Ba'ath Party socialist ideology.

In the mid 1990s Syria entered a recession and experienced a sharp drop in economic growth copmared to the early years of the decade. In the late 1990s the economic growth was around 1.5%, which was insufficient as the population growth was between 3% and 3.5%. This made the GDP per capita negative. Another symptom of the crisis was statism in foreign trade. Syria's economic crisis occurred along with the recession in world markets and a major blow to its economy was the drop in the price of oil in 1998. Nevertheless, the rise of the price of oil in 1999 eased Syrian economic predicaments to some extent. Another difficulty to the Syrian economy was a drought that occurred in 1999. It was one of the worst droughts in the century. It caused a drop of 25% - 30% in crop yields as compared with 1997 and 1998. Assad's government implemented emergency measures that included loans and compensation to farmers and distribution of fodder free of charge in order to save sheep and cattle. However, those steps were limited and did not make any real difference.

The Syrian economy had problems with population growth. Assad's government tried to decrease the population growth, but only with marginal success. One of the signs of the economic stagnation was the lack of progress in the talks with the European Union on signing an association agreement. The major reason for this problem was the difficulty facing Syria to meet EU demands to open the economy and introduce reforms. Marc Pierini, head of the EU delegation in Damascus, said that if the Syrian economy was not modernized it could not benefit from closer ties to the EU. Nevertheless, Assad's government offered a 20% paychek increase to the civil servants on the anniversary day of the "Correction Revolution" which brought Assad to power. The foreign press criticized the Syrian reluctance to liberalize its economy. Assad's government refused to modernize the bank system, refrained from allowing private banks and from opening a stock exchange.

As one of his strategies to maintain power, Hafez developed a state sponsored cult of personality. As Assad had ambitions to become a pan Arab leader, he often represented himself as a successor of Gamal Abdul Nasser. To be sure, since his ascendancy in November 1970, which symbolically occurred a few weeks after Nasser's death, Assad had alluded in various ways to the fact that he regarded himself as Nasser's successor. He modeled his presidential system after Nasser's and hailed Nasser for his pan Arabic leadership, while displaying Nasser's photos alongside his own posters in public places.

Nonetheless, a greater hero and a supreme model for Assad was Salah ad-Din, the legendary Muslim Kurdish leader who in the 12th century succeeded in unifying the Muslim East, defeating the Crusaders in 1187 at Hittin and subsequently conquering Jerusalem. Assad demonstrated his admiration for Salah ad-Din and his heritage by having in his office a large painting depicting Salah ad-Din's tomb in Damascus and issuing a currency bill with Salah ad-Din's figure. In his speeches and conversations, Assad frequently hailed Salah ad-Din's successes and his victory over the crusaders while equating Israel with the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Crusaders' state.

Portraits of him, often depicting him engaging in heroic activities, were placed in every public space. He named numerous places and institutions in Syria after himself and other members of his family. At school, children were taught to sing songs of adulation about Hafez al-Assad. Teachers began each lesson with the song "Our eternal leader, Hafez al-Assad". In some cases, he portrayed himself with apparently divine properties. Sculptures and portraits depicted him alongside the prophet Mohammad, while following his mother's death, the government produced portraits of her surrounded by a halo. Syrian officials were made to refer to him as the 'Sanctified one' (al-Muqaddas). This strategy of creating a cult of personality was pursued further by Hafez's son Bashar ``the beast" al-Assad.

By the late 1990s Assad increasingly suffered from ill health.

American diplomats that met him stated that Assad had difficulties

remaining focused during meetings and that he exhibited weariness and

fatigue. It was also speculated that Assad was incapable of functioning

for

more than two hours a day. However, his spokesperson refrained from

responding to such speculations. Moreover Assad's official routine in

1999

did not have any significant changes from that of the previous decade.

Assad continued to have meetings and traveled abroad a few times, of

which

the most notable was his visit to Moscow in July. Nevertheless

Assad's

government was accustomed to work without his direct intervention or

involvement in day - to - day affairs. On 10 June 2000 Assad died due to a heart attack he suffered while speaking on the telephone with Lebanese prime minister Salim al-Hoss. His funeral was held three days later, on 13 June. Hafez al-Assad is buried together with his son Bassel in a mausoleum in his hometown of Qardaha.