<Back to Index>

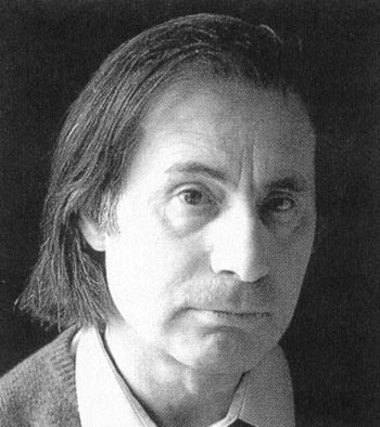

- Composer Alfred Schnittke, 1934

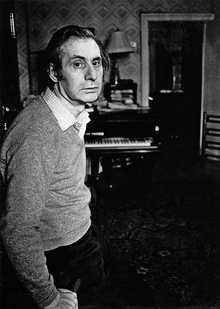

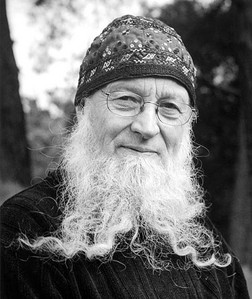

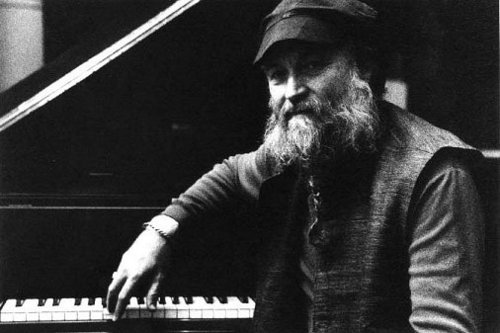

- Composer Terry Riley, 1935

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Schnittke (Russian: Альфре́д Га́рриевич Шни́тке (Al'fred Garrievič Šnitke); Engels, November 24, 1934 – Hamburg, August 3, 1998) was a Soviet composer. Schnittke's early music shows the strong influence of Dmitri Shostakovich. He developed a polystylistic technique in works such as the epic First Symphony (1969 - 1972) and First Concerto Grosso (1977). In the 1980s, Schnittke's music began to become more widely known abroad with the publication of his Second (1980) and Third (1983) String Quartets and the String Trio (1985); the ballet Peer Gynt (1985 - 1987); the Third (1981), Fourth (1984), and Fifth (1988) Symphonies; and the Viola (1985) and 1st Cello (1985 - 1986) Concertos. As his health deteriorated, Schnittke's music started to abandon much of the extroversion of his polystylism and retreated into a more withdrawn, bleak style.

Schnittke's father, Harry Viktorovich Schnittke (1914 - 1975, rus.), was Jewish and born in Frankfurt. He moved to the USSR in 1927 and worked as a journalist and translator from the Russian language into German. His mother, Maria Iosifovna Schnittke (née Vogel, 1910 - 1972), was a Volga German born in Russia. Schnittke's paternal grandmother, Tea Abramovna Katz (1889 - 1970), was a philologist, translator, and editor of German - language literature.

Alfred Schnittke was born in Engels in the Volga - German Republic of the RSFSR, Soviet Union. He began his musical education in 1946 in Vienna where his father had been posted. It was in Vienna, Schnittke's biographer Alexander Ivashkin writes, where "he fell in love with music which is part of life, part of history and culture, part of the past which is still alive." "I felt every moment there," the composer wrote, "to be a link of the historical chain: all was multi - dimensional; the past represented a world of ever - present ghosts, and I was not a barbarian without any connections, but the conscious bearer of the task in my life." Schnittke's experience in Vienna "gave him a certain spiritual experience and discipline for his future professional activities. It was Mozart and Schubert, not Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff, whom he kept in mind as a reference point in terms of taste, manner and style. This reference point was essentially Classical ... but never too blatant."

In 1948, the family moved to Moscow. Schnittke completed his graduate work in composition at the Moscow Conservatory in 1961 and taught there from 1962 to 1972. Evgeny Golubev was one of his composition teachers. Thereafter, he earned his living chiefly by composing film scores, producing nearly 70 scores in 30 years. Schnittke converted to Christianity and possessed deeply held mystic beliefs, which influenced his music.

Schnittke and his music were often viewed suspiciously by the Soviet bureaucracy. His First Symphony was effectively banned by the Composers' Union. After he abstained from a Composers' Union vote in 1980, he was banned from traveling outside of the USSR. In 1985, Schnittke suffered a stroke that left him in a coma. He was declared clinically dead on several occasions, but recovered and continued to compose.

In 1990, Schnittke left Russia and settled in Hamburg. His health remained poor, however. He suffered several more strokes before his death on August 3, 1998, in Hamburg, at the age of 63. He was buried, with state honors, at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where many other prominent Russian composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich, are interred.

Schnittke's early music shows the strong influence of Dmitri Shostakovich, but after the visit of the Italian composer Luigi Nono to the USSR, he took up the serial technique in works such as Music for Piano and Chamber Orchestra (1964). However, Schnittke soon became dissatisfied with what he termed the "puberty rites of serial self - denial." He created a new style which has been called "polystylism", where he juxtaposed and combined music of various styles past and present. He once wrote, "The goal of my life is to unify serious music and light music, even if I break my neck in doing so." His first concert work to use the polystylistic technique was the Second Violin Sonata, Quasi una sonata (1967 - 1968). He experimented with techniques in his film work, as shown by much of the sonata appearing first in his score for the animation short The Glass Harmonica. He continued to develop the polystylistic technique in works such as the epic First Symphony (1969 - 1972) and First Concerto Grosso (1977). Other works were more stylistically unified, such as his Piano Quintet (1972 - 1976), written in memory of his recently deceased mother.

In the 1980s, Schnittke's music began to become more widely known abroad, thanks in part to the work of émigré Soviet artists such as the violinists Gidon Kremer and Mark Lubotsky. Despite constant illness, he produced a large amount of music, including important works such as the Second (1980) and Third (1983) String Quartets and the String Trio (1985); the Faust Cantata (1983), which he later incorporated in his opera Historia von D. Johann Fausten; the ballet Peer Gynt (1985 - 1987); the Third (1981), Fourth (1984) and Fifth (1988) Symphonies (the last of which is also known as the Fourth Concerto Grosso) and the Viola (1985) and 1st Cello (1985 - 1986) concertos.

As his health deteriorated, Schnittke started to abandon much of the extroversion of his polystylism and retreated into a more withdrawn, bleak style, quite accessible to the lay listener. The Fourth Quartet (1989) and Sixth (1992), Seventh (1993) and Eighth (1994) symphonies are good examples of this. Some Schnittke scholars, such as Gerard McBurney, have argued that it is the late works that will ultimately be the most influential parts of Schnittke's output. After a stroke in 1994 left him almost completely paralyzed, Schnittke largely ceased to compose. He did complete some short works in 1997 and also a Ninth Symphony; its score was almost unreadable because he had written it with great difficulty with his left hand. The Ninth Symphony was first performed on 19 June 1998 in Moscow in a version deciphered – but also 'arranged' – by Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, who conducted the premiere. After hearing a tape of the performance, Schnittke indicated he wanted it withdrawn.

After Schnittke's death, others worked to decipher his score. Nikolai Korndorf died before he could complete the task, which was continued and completed by Alexander Raskatov. In Raskatov's version, the three orchestral movements of Schnittke's symphony may be followed by a choral fourth, which is Raskatov's own Nunc Dimittis (in memoriam Alfred Schnittke). This version was premiered in Dresden, Germany June 16, 2007. Andrei Boreyko also has a version of the symphony.

Terrence Mitchell Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician intrinsically associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music and was a pioneer of the movement. His work has been deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music.

Born in Colfax, California, Riley studied at Shasta College, San Francisco State University, and the San Francisco Conservatory before earning an MA in composition at the University of California, Berkeley, studying with Seymour Shifrin and Robert Erickson. He was involved in the experimental San Francisco Tape Music Center working with Morton Subotnick, Steve Reich, Pauline Oliveros, and Ramon Sender. His most influential teacher, however, was Pandit Pran Nath (1918 - 1996), a master of Indian classical voice, who also taught La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela. Riley made numerous trips to India over the course of their association to study and to accompany him on tabla, tambura, and voice. Throughout the 1960s he traveled frequently around Europe as well, taking in musical influences and supporting himself by playing in piano bars, until he joined the Mills College faculty in 1971 to teach Indian classical music. Riley was awarded an Honorary Doctorate Degree in Music at Chapman University in 2007.

Riley also cites John Cage and "the really great chamber music groups of John Coltrane and Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Bill Evans, and Gil Evans" as influences on his work, demonstrating how he pulled together strands of Eastern music, the Western avant garde, and jazz.

Also during the 1960s were the famous "All - Night Concerts", during which Riley performed mostly improvised music from evening until sunrise, using an old organ harmonium ("with a vacuum cleaner motor blower blowing into the ballasts") and tape - delayed saxophone. When he finally wanted a break, after hours of playing, he played back looped saxophone fragments recorded throughout the evening. For several years he continued to put on these concerts, to which people came with sleeping bags, hammocks and their whole families.

Riley began his long lasting association with the Kronos Quartet when he met founder David Harrington while at Mills. Over the course of his career, Riley composed 13 string quartets for the ensemble, in addition to other works. He wrote his first orchestral piece, Jade Palace, in 1991, and continued to pursue that avenue, with several commissioned orchestral compositions following. Riley was also currently performing and teaching both as an Indian raga vocalist and as a solo pianist.

He has a son named Gyan Riley, who is a guitarist. He was chosen by Animal Collective to perform at the All Tomorrow's Parties festival in May 2011.

While his early endeavors were influenced by Stockhausen, Riley changed direction after first encountering La Monte Young, in whose Theater of Eternal Music he later performed in 1965 - 66. The String Quartet (1960) was Riley's first work in this new style; it was followed shortly after by a string trio, in which he first employed the repetitive short phrases for which he and minimalism are now known.

His music is usually based on improvising through a series of modal figures of different lengths, such as in In C (1964) and the Keyboard Studies. The first performance of In C was given by Steve Reich, Jon Gibson, Pauline Oliveros, and Morton Subotnick. Its form was an innovation: The piece consists of 53 separate modules of roughly one measure apiece, each containing a different musical pattern but each, as the title implies, in the key of C. One performer beats a steady pulse of Cs on the piano to keep tempo. The others, in any number and on any instrument, perform these musical modules following a few loose guidelines, with the different musical modules interlocking in various ways as time goes on. To some extent, though, critics have focused too obsessively on In C, thereby ignoring the full range of Riley's work and innovations. The Keyboard Studies are similarly structured, a single performer version of the same concept.

In the 1950s he was already working with tape loops, a technology then in its infancy, and he has continued manipulating tapes to musical effect, both in the studio and in live performance, throughout his career. An early tape loop piece titled The Gift (1963) featured the trumpet playing of Chet Baker. Riley has composed in just intonation as well as microtonal pieces.

Riley's collaborators have included the Rova Saxophone Quartet, Pauline Oliveros, the ARTE Quartett, and, as mentioned, the Kronos Quartet.

Riley's famous overdubbed electronic album A Rainbow in Curved Air (recorded 1967, released 1969) inspired many later developments in electronic music, including Pete Townshend's synthesizer parts on The Who's "Won't Get Fooled Again" and "Baba O'Riley", the latter named in tribute to Riley as well as to Meher Baba. The recording had a significant impact on the development of ambient music and progressive rock and predated the electronic jazz - rock fusion of Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, and others.

As Rainbow demonstrates, Riley performs on multiple keyboard instruments, but his principal instrument is actually the acoustic piano. Riley's 1995 Lisbon Concert recording features him in a solo piano format, improvising on his own works. In the liner notes Riley cites Art Tatum, Bud Powell and Bill Evans as his piano "heroes," illustrating the central importance of jazz to his conceptions, and his playing bears some notable similarities to that of Keith Jarrett. (The album title invites this comparison.)

Riley's work and various innovations have influenced many others in various genres, including John Adams, Brian Eno, Robert Fripp, Philip Glass, Frederic Rzewski and Tangerine Dream.