<Back to Index>

- Architect Nikolai Alexandrovich Ladovsky, 1881

PAGE SPONSOR

Nikolai Alexandrovich Ladovsky (Russian: Николай Александрович Ладовский) (1881, Moscow - 1941, Moscow) was a Russian avant garde architect and educator, leader of the rationalist movement in 1920s architecture, an approach emphasizing human perception of space and shape. Ladovsky is known as the founder of modern Soviet and Russian schools of architectural training; his classes of 1920 - 1932 in VKhUTEMAS shaped the generation of Soviet architects active throughout the period of Stalinist architecture and subsequent decades.

Ladovsky's life prior to his training in the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (1914 – 1917) remains unknown. His private archives were lost in World War II; all recorded information relies on two statements made by the architect himself:

- In 1914, applying to the School at the age of 33, Ladovsky asserted that he worked in architecture for 16 years (i.e., from the age of 16 or 17), and was awarded three professional prizes for the drafts of public buildings in Perm, Blagoveshchensk and Ananiv; the earliest of these awards dated 1901. None of these drafts ever materialized. According to the same statement, in 1907 - 1914 Ladovsky worked continuously in Saint Petersburg, in architectural design and construction management roles.

- In 1921 Ladovsky asserted that he worked 4 years in a foundry and 15 years in practical construction.

In 1915,

when the School celebrated its 50th birthday, Ladovsky

became a speaker for a group of students demanding change

in their training program. The group, in particular,

voiced aversion to the decadent Art Nouveau (already

obsolete), and the need to invite the best architects of

the new

movement -

that is, Neoclassical Revival - like Ivan Zholtovsky and Alexey Shchusev. They joined the

faculty in 1916. Despite future rivalry for the VKhUTEMAS

chair, Ladovsky retained deep respect for Zholtovsky - for

his practical achievements as well as his teaching style.

Ladovsky graduated from the School in the year of the economic collapse that accompanied the Russian revolution of 1917. To survive, Zholtovsky and his graduates accepted the Bolshevik's invitation to head the architectural department of Mossovet, engaged mostly in street repairs and temporary propaganda decorations. Training continued at the work site for a year and a half. However, by the beginning of 1919 the younger architects realized the need to break away from Zholtovsky's historical style - to avant garde architecture. In May – November, 1919 this group (Ladovsky, Vladimir Krinsky, Alexander Rukhlyadev and others), joined by artists like Alexander Rodchenko, gained state approval and incorporated as Zhivskulptarkh (Russian: Живскульптарх, Commission for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture). Internal disputes within the Commission and its public exhibition shaped Ladovsky's concept of art, architecture and shape:

Sculpture is an art of handling shape. Architecture is an art of handling space. Space is used by all kinds of art, but only architecture enables us to read the fabric of space correctly. Architects' material is space, not stone. Sculptural shape in architecture is subordinate to space. Graphic arts are subordinate to both space and sculptural shape.

At the same time Ladovsky clearly distanced himself from the nihilist wing of the Constructivists who reduced architecture to simple engineering:

Structural engineering belongs to architecture inasmuch as structure defines space. Engineers are here to obtain maximum output from minimal material inputs. Their approach has nothing common with art; it may satisfy the architect only by accident. ... Exterior facade should not barely reflect the inner contents, but have a value of its own.

In 1920

these public statements and a series of Zhivskulparch shows

suddenly established an unknown Ladovsky as the leader of

a new school, clearly opposed to Zholtovsky's

neoclassicism and the emerging constructivist architecture. In

December 1920 Ladovsky

became a regular speaker at the Institute of Artistic

Culture (Inkhuk);

here in the course of a five month convention of

architects he forged the doctrine of "rationalism," an

approach emphasizing human perception of space and shape,

and placing art of architecture above bare engineering.

In 1920 VKhUTEMAS students revolted against Zholtovsky, too. Heads of two other departments, Alexey Shchusev and Ivan Rylsky, and MVTU professors Leonid Vesnin and Fyodor Schechtel also came under fire. Ladovsky triumphantly presented his program of training at VKhUTEMAS and joined the faculty. Initially he was subordinate to the Department of Architecture and the course framework imposed by Zholtovsky.

Ladovsky and his associates, Vladimir Krinsky and Nikolay Dokuchaev, were granted full freedom to set their own training program for the season of 1921 - 1922. Their new department, known as OBMAS (Russian: ОБМАС, Объединённые мастерские) - United Workshops, indeed united students of now unpopular, 'old school' professors.

To break

away from limitations of classical architectural training,

Ladovsky designed a completely new course developing

spatial perception - prior

to exposing

students to elements of architectural legacy. Key elements

of his program persisted until the end of the 20th

century.

Notable OBMAS graduates, who were successfully integrated into Stalinist architecture, include Georgy Krutikov (designer of the Flying City utopia), Ivan Volodko (designer of post-war reconstruction of Minsk), Yevgeny Yocheles (designer of the Glavsevmorput building in Moscow and plattenbau districts of Vladivostok and Togliatti), landscape designer Mikhail Korzhev (designer of Moscow State University campus park and Izmailovo park). A talented graduate of Ladovsky school, Gevorg Kochar, was arrested in 1937 in Yerevan (along with another VKhuTEMAS graduate, Mikael Mazmanyan), sentenced for 15 years on political charges, and ended up in Norilsk as a sharashka architect. Acquitted after 17 years of prison and exile, Kochar successfully worked as chief architect of Krasnoyarsk (being a supervisor of exiled Miron Merzhanov) and Yerevan.

In the season of 1923 - 1924 VKhuTEMAS created a new General Department providing mandatory two-year introduction courses to students of all departments. Ladovsky's course on Space, delivered by his senior students, became one of the core subjects in this program. Ladovsky's own studies and publications of the period attempted to formulate a rational, objective model and rules of human perception of space, shape and color (assuming, by default, that such rules exist and can be reliably formulated). His amended doctrine of "rationalism" called for implementing these rules of perception in practical architecture and city planning. He further alienated himself from the Constructivist majority by emphasizing the need to assist human orientation in the cities, a concept disregarded by Constructivists:

Architect designs shape by adding elements that are neither "technical" nor "utilitarian" - elements that can be broadly defined as setting architectural motives. These motives must be rational and must serve the utmost human need - the need to orient in space.

ASNOVA, the union of rationalist architects, was founded in 1923; members typically belonged to VKhuTEMAS faculty. Their first public success came with winning the 1924 contest for the International Red Stadium in Sparrow Hills, Moscow (lead designer: Vladimir Krinsky). In the following two years Ladovsky personally led the design team, producing detailed construction plans. However, in the autumn of 1927 the project was canceled citing unsuitable geological foundation of the chosen site.

In 1925 Ladovsky teamed with El Lissitzky to design new housing for Ivanovo; their plans were based on arranging residential blocks at 120° in zigzag or star patterns. This approach allowed cost saving on common use staircases, ventilation and plumbing lines. One 12 segment building of this type, combining both star and zigzag junctions, was completed in Khamovniki District of Moscow. The next year, Ladovsky and Lissitzky released the first (and only) volume of Izvestia ASNOVA (Russian: Известия АСНОВА), compiled mostly from Ladovsky's works.

However, Ladovsky lost the race to constructivists as early as in 1922, during the contest for the Palace of Labor in Moscow. Ladovsky anticipated that the conservative members of the jury would fail avant garde entries, and persuaded his group members to boycott the contest. In fact, it became a showcase of constructivism (Vesnin brothers) and symbolic romanticism (Ilya Golosov); constructivists quickly took the lead while Ladovsky dedicated all his time to teaching. Unlike rationalism, which required special schooling, constructivism could be mastered by simply copying the novel elements of existing designs. As a result, fresh graduates (Arkady Mordvinov) and old masters (Alexey Shchusev) easily integrated themselves into the constructivist movement, and by 1926 - 1928 its domination was absolute.

Ladovsky

realized that ASNOVA represented VKhuTEMAS faculty rather

than practical architects, and in 1928 set up ARU (Russian: АРУ, Объединение архитекторов -

урбанистов), composed of VKhuTEMAS students

(graduates of 1928 - 1930). As the name implied, the group

focused on urban planning for the sustainable development of

explosively growing cities. This group and Ladovsky

personally generated a series of urban growth programs,

including the Parabola. This plan tried

to break away from the traditional, singe - center concentric model of

development. Instead, Ladovsky proposed linear extension

of the city center along a single radius; concentric housing and

industrial zones were to unfold along this radius in a horseshoe pattern.

This, according to Ladovsky, reduced the need for high rise construction in

the center and traffic congestion. Parabola,

initially published in 1930, was further developed in post

war years by Konstantinos Doxiadis but rejected

at home.

The 1932 crackdown on avant garde artists that preceded the rise of Stalinist architecture did not mean that Ladovsky or Constructivist leaders became instantly unemployed. On the contrary, Ladovsky was assigned to manage Mossovet Fifth planning workshop, responsible for the redesign of Zamoskvorechye and Yakimanka territories. In 1933 - 1935, prior to the enactment of Stalin's master plan for the reconstruction of Moscow, but definitely in accordance with its policies, Ladovsky designed a redevelopment plan for Zamoskvorechye. He proposed converting narrow Bolshaya Ordynka Street into a wide avenue, replacing all historical buildings and the existing street network with monotonous rows of new high rise buildings similar to later, 1970s, Soviet designs. Like most of the 1935 master plan, it never materialized - due to high costs and World War II.

Redevelopment plan for the island between Moskva River and Vodootvodny Canal called for the complete disappearance of Sadovnicheskaya Street - instead, the island was cut into five nearly identical large blocks with four pairs of towers facing the river. The part beyond Garden Ring, with a single lean tower and a half - circle of offices facing the canal, is surprisingly similar to what was actually built there in 1990s - 2000s (Swissotel Krasnye Holmy and adjacent business park).

Ladovsky took part in the first and third rounds of the Palace of Soviets contest. His first entry (1931) consisted of a hemispherical dome standing on an inclined slab and a free standing, 35 floors office tower. The second entry (1933) omitted the tower. In 1932 - 1933 Ladovsky also entered numerous architectural design contests of lesser scale with no success - except for the Moscow Metro designs.

Metro

stations, completed in 1935, and a presentation of

Zamoskvorechye plan in July, 1935 issue of Architecture

of Moscow (Russian: Архитектура Москвы)

became his last public statements. Ladovsky's life in late

1930s and circumstances of his death remain unknown to the

general public. Artist May Miturich (1925 –

2005), whose father, Pyotr Miturich, moved into

Ladovsky's private workshop in 1941, asserted that

Ladovsky committed suicide.

Only four physical structures were ever completed to Ladovsky's own, undisputed, design; three of them were eventually rebuilt beyond recognition:

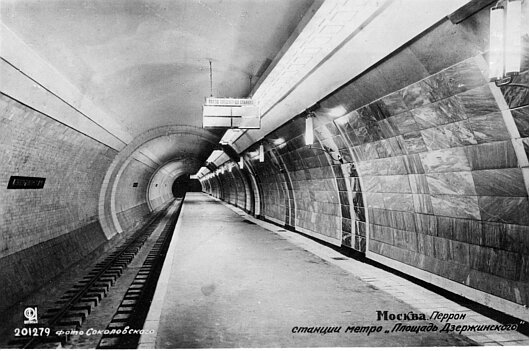

- Underground halls of Lubyanka (originally Dzerzhinskaya) station of Moscow Metro, commissioned in 1935. In 1968 - 1972, as the station was expanded, Ladovsky's interiors were stripped and rebuilt to a different design. Some tiling dating back to 1935 survived in the extreme ends of the side halls.

- Surface entrance to Krasniye Vorota station, 1935. The structure remains practically intact.

- Two residential buildings inside the block at 6, Tverskaya Street, designed in 1928 and completed in 1931. Initially they were connected by a single story retail store; in late 1930 the store was demolished and the buildings incorporated into a front row of buildings designed by Arkady Mordvinov.