<Back to Index>

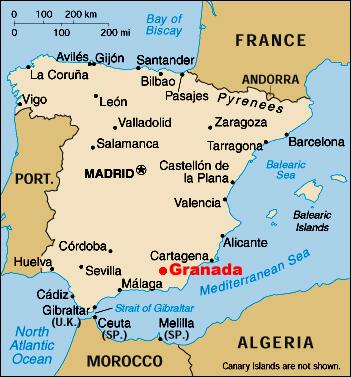

- Granada, España

La Alhambra, 10th

Century

PAGE SPONSOR

Alhambra, the complete form of which was Calat Alhambra, is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Andalusia, Spain. It was constructed during the mid 10th century by the Umaid Arabic ruler Badis ben Habus of the Kingdom of Granada in al-Andalus, occupying the top of the hill of the Assabica on the southeastern border of the city of Granada.

The Alhambra's Islamic palaces were built for the last Muslim Emirs in Spain and its court, of the Nasrid dynasty. After the Reconquista (reconquest) by the Reyes Católicos ("Catholic Monarchs") in 1492, some portions were used by the Christian rulers. The Palace of Charles V, built by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1527, was inserted in the Alhambra within the Nasrid fortifications. After being allowed to fall into disrepair for centuries, the Alhambra was "discovered" in the 19th century by European scholars and travelers, with restorations commencing. It is now one of Spain's major tourist attractions, exhibiting the country's most significant and well known Berber Islamic architecture, together with 16th century and later Christian building and garden interventions. The Alhambra is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the inspiration for many songs and stories.

Moorish poets described it as "a pearl set in emeralds," in allusion to the color of its buildings and the woods around them. The palace complex was designed with the mountainous site in mind and many forms of technology were considered. The park (Alameda de la Alhambra), which is overgrown with wildflowers and grass in the spring, was planted by the Moors with roses, oranges and myrtles; its most characteristic feature, however, is the dense wood of English elms brought by the Duke of Wellington in 1812. The park has a multitude of nightingales and is usually filled with the sound of running water from several fountains and cascades. These are supplied through a conduit 8 km (5.0 mi) long, which is connected with the Darro at the monastery of Jesus del Valle, above Granada.

Despite long neglect, willful vandalism and some ill - judged restoration, the Alhambra endures as an atypical example of Muslim art in its final European stages, relatively uninfluenced by the direct Byzantine influences found in the Mezquita of Córdoba. The majority of the palace buildings are quadrangular in plan, with all the rooms opening on to a central court; and the whole reached its present size simply by the gradual addition of new quadrangles, designed on the same principle, though varying in dimensions, and connected with each other by smaller rooms and passages. The Alhambra was extended by the different Muslim rulers who lived in the complex. However, each new section that was added followed the consistent theme of "paradise on earth". Column arcades, fountains with running water, and reflecting pools were used to add to the aesthetic and functional complexity. In every case, the exterior was left plain and austere. Sun and wind were freely admitted. Blue, red and a golden yellow, all somewhat faded through lapse of time and exposure, are the colors chiefly employed.

The decoration consists, as a rule, of Arabic inscriptions that are manipulated into sacred geometrical patterns wrought into arabesques. Painted tiles are largely used as paneling for the walls. The palace complex is designed in the Mudéjar style which is characteristic of western elements reinterpreted into Islamic forms and widely popular during the Reconquista, the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims by the Christian kingdoms.

The Alhambra did not have a master plan for the total site design, so its overall layout is not orthogonal nor organized. As a result of the site's many construction phases: from the original 9th century citadel, through the 14th century Muslim palaces, to the 16th century palace of Charles V; some buildings are at odd positioning to each other. The terrace or plateau where the Alhambra sits measures about 740 meters (2,430 ft) in length by 205 meters (670 ft) at its greatest width. It extends from west - northwest to east - southeast and covers an area of about 142,000 square meters (1,530,000 sq ft). The Alhambra's most westerly feature is the alcazaba (citadel), a strongly fortified position. The rest of the plateau comprises a number of Moorish palaces, enclosed by a fortified wall, with thirteen towers, some defensive and some providing vistas for the inhabitants. The river Darro passes through a ravine on the north and divides the plateau from the Albaicín district of Granada. Similarly, the Assabica valley, containing the Alhambra Park on the west and south, and, beyond this valley, the almost parallel ridge of Monte Mauror, separate it from the Antequeruela district. Another ravine separates it from the Generalife.

The decorations within the palaces typified the remains of Moorish dominion within Spain and ushered in the last great period of Andalusian art in Granada. With little of the Byzantine influence of contemporary Abassid architecture, artists endlessly reproduced the same forms and trends, creating a new style that developed over the course of the Nasrid Dynasty. The Nasrids used freely all the stylistic elements that had been created and developed during eight centuries of Muslim rule in the Peninsula, including the Calliphal horseshoe arch, the Almohad sebka (a grid of rhombuses), the Almoravid palm, and unique combinations of them, as well as innovations such as stilted arches and muqarnas (stalactite ceiling decorations). The isolation from the rest of Islam plus the commercial and political relationship with the Christian kingdoms also influenced building styles.

Columns and muqarnas appear in several chambers, and the interiors of numerous palaces are decorated with arabesques and calligraphy. The arabesques of the interior are ascribed to, among other sultans, Yusuf I, Mohammed V, and Ismail I, Sultan of Granada.

After the Christian conquest of the city in 1492, the conquerors began to alter the Alhambra. The open work was filled up with whitewash, the painting and gilding effaced, and the furniture soiled, torn, or removed. Charles I (1516 - 1556) rebuilt portions in the Renaissance style of the period and destroyed the greater part of the winter palace to make room for a Renaissance style structure which was never completed. Philip V (1700 - 1746) Italianized the rooms and completed his palace in the middle of what had been the Moorish building; he had partitions constructed which blocked up whole apartments.

Over subsequent centuries the Moorish art was further damaged, and in 1812 some of the towers were destroyed by the French under Count Sebastiani. In 1821, an earthquake caused further damage. Restoration work was undertaken in 1828 by the architect José Contreras, endowed in 1830 by Ferdinand VII. After the death of Contreras in 1847, it was continued with fair success by his son Rafael (d. 1890) and his grandson. Designed to reflect the very beauty of Paradise itself, the Alhambra is made up of gardens, fountains, streams, a palace, and a mosque, all within an imposing fortress wall, flanked by 13 massive towers.

Completed towards the end of Muslim rule of Spain by Yusuf I (1333 - 1353) and Muhammed V, Sultan of Granada (1353 - 1391), the Alhambra is a reflection of the culture of the last centuries of the Moorish rule of Al Andalus, reduced to the Nasrid Emirate of Granada. It is a place where artists and intellectuals had taken refuge as the Reconquista by Spanish Christians won victories over Al Andalus. The Alhambra integrates natural site qualities with constructed structures and gardens, and is a testament to Moorish culture in Spain and the skills of Muslim, Jewish and Christian artisans, craftsmen and builders of their era. The literal translation of Alhambra, "the red (female)," reflects the color of the red clay of the surroundings of which the fort is made. The buildings of the Alhambra were originally whitewashed; however, the buildings as seen today are reddish. Another possible origin of the name is the tribal designation of the Nasrid Dynasty, known as the Banu al-Ahmar Arabic: Sons of the Red (male), a sub-tribe of the Qahtanite Banu Khazraj tribe. One of the early Nasrid ancestors was nicknamed Yusuf Al Ahmar (Yusuf the Red) and hence the (Nasrid) fraction of the Banu Khazraj took up the name of Banu al-Ahmar.

The first reference to the Qal‘at al-Ḥamra was during the battles between the Arabs and the Muladies (people of mixed Arab and European descent) during the rule of the ‘Abdullah ibn Muhammad (r. 888 - 912). In one particularly fierce and bloody skirmish, the Muladies soundly defeated the Arabs, who were then forced to take shelter in a primitive red castle located in the province of Elvira, presently located in Granada. According to surviving documents from the era, the red castle was quite small, and its walls were not capable of deterring an army intent on conquering. The castle was then largely ignored until the eleventh century, when its ruins were renovated and rebuilt by Samuel ibn Naghrela, vizier to the emir Badis ben Habus of the Zirid Dynasty of Al Andalus, in an attempt to preserve the small Jewish settlement also located on the Sabikah hill.

Ibn Nasr, the founder of the Nasrid Dynasty, was forced to flee to Jaén to avoid persecution by King Ferdinand III of Castile and the Reconquista supporters working to end Spain's Moorish rule. After retreating to Granada, Ibn-Nasr took up residence at the Palace of Badis ben Habus in the Alhambra. A few months later, he embarked on the construction of a new Alhambra fit for the residence of a sultan. According to an Arab manuscript since published as the Anónimo de Granada y Copenhague,

- This year, 1238 Abdallah ibn al-Ahmar climbed to the place called "the Alhambra" inspected it, laid out the foundations of a castle and left someone in charge of its construction...

The design included plans for six palaces, five of which were grouped in the northeast quadrant forming a royal quarter, two circuit towers, and numerous bathhouses. During the reign of the Nasrid Dynasty, the Alhambra was transformed into a palatine city, complete with an irrigation system composed of acequias for the gardens of the Generalife located outside the fortress. Previously, the old Alhambra structure had been dependent upon rainwater collected from a cistern and from what could be brought up from the Albaicín. The creation of the Sultan's Canal solidified the identity of the Alhambra as a palace - city rather than a defensive and ascetic structure.

The Muslim ruler Muhammad XII of Granada surrendered the Emirate of Granada in 1492 without the Alhambra itself being attacked when the forces of Los Reyes Católicos, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile, took the surrounding territory with an overwhelming force of numbers.

The Alhambra resembles many medieval Christian strongholds in its threefold arrangement as a castle, a palace and a residential annex for subordinates. The alcazaba or citadel, its oldest part, is built on the isolated and precipitous foreland which terminates the plateau on the northwest. That is all massive outer walls, towers and ramparts are left. On its watchtower, the Torre de la Vela, 25 m (85 ft) high, the flag of Ferdinand and Isabella was first raised, in token of the Spanish conquest of Granada on 2 January 1492. A turret containing a large bell was added in the 18th century and restored after being damaged by lightning in 1881. Beyond the Alcazaba is the palace of the Moorish rulers, or Alhambra properly so-called; and beyond this, again, is the Alhambra Alta (Upper Alhambra), originally tenanted by officials and courtiers.

Access from the city to the Alhambra Park is afforded by the Puerta de las Granadas (Gate of Pomegranates), a triumphal arch dating from the 15th century. A steep ascent leads past the Pillar of Charles V, a fountain erected in 1554, to the main entrance of the Alhambra. This is the Puerta de la Justicia (Gate of Judgment), a massive horseshoe archway surmounted by a square tower and used by the Moors as an informal court of justice. The hand of Fatima, with fingers outstretched as a talisman against the evil eye, is carved above this gate on the exterior; a key, the symbol of authority, occupies the corresponding place on the interior. A narrow passage leads inward to the Plaza de los Aljibes (Place of the Cisterns), a broad open space which divides the Alcazaba from the Moorish palace. To the left of the passage rises the Torre del Vino (Wine Tower), built in 1345 and used in the 16th century as a cellar. On the right is the palace of Charles V, a smaller Renaissance building.

The Royal Complex consists of three main parts: Mexuar, Serallo, and the Harem. The Mexuar is modest in decor and houses the functional areas for conducting business and administration. Strapwork is used to decorate the surfaces in Mexuar. The ceilings, floors, and trim are made of dark wood and are in sharp contrast to white, plaster walls. Serallo, built during the reign of Yusuf I in the 14th century, contains the Patio de los Arrayanes (Court of the Myrtles). Brightly colored interiors featured dado panels, yesería, azulejo, cedar and artesonado. Artesonado are highly decorative ceilings and other woodwork. Lastly, the Harem is also elaborately decorated and contains the living quarters for the wives and mistresses of the Berber monarchs. This area contains a bathroom with running water (cold and hot), baths, and pressurized water for showering. The bathrooms were open to the elements in order to allow in light and air.

The present entrance to the Palacio Árabe, or Casa Real (Moorish palace), is by a small door from which a corridor connects to the Patio de los Arrayanes (Court of the Myrtles), also called the Patio de la Alberca (Court of the Blessing or Court of the Pond), from the Arabic birka, "pool". The birka helped to cool the palace and acted as a symbol of power. Because water was usually in short supply, the technology required to keep these pools full was expensive and difficult. This court is 42 m (140 ft) long by 22 m (74 ft) broad, and in the center there is a large pond set in the marble pavement, full of goldfish, and with myrtles growing along its sides. There are galleries on the north and south sides; the southern gallery is 7 m (23 ft) high and supported by a marble colonnade. Underneath it, to the right, was the principal entrance, and over it are three windows with arches and miniature pillars. From this court, the walls of the Torre de Comares are seen rising over the roof to the north and reflected in the pond.

The Salón de los Embajadores (Hall of the Ambassadors) is the largest in the Alhambra and occupies all the Torre de Comares. It is a square room, the sides being 12 m (37 ft) in length, while the center of the dome is 23 m (75 ft) high. This was the grand reception room, and the throne of the sultan was placed opposite the entrance. The grand hall projects from the walls of the palace, providing views in three directions. In this sense, it was a "mirador" from which the palace's inhabitants could gaze outward to the surrounding landscape. It was in this setting that Christopher Columbus received Isabel and Ferdinand's support to sail to the New World. The tiles are nearly 4 ft (1.2 m) high all round, and the colors vary at intervals. Over them is a series of oval medallions with inscriptions, interwoven with flowers and leaves. There are nine windows, three on each facade, and the ceiling is decorated with white, blue and gold inlays in the shape of circles, crowns and stars. The walls are covered with varied stucco works, surrounding many ancient escutcheons.

The Patio de los Leones (Court of the Lions) is an oblong court, 116 ft (35 m) in length by 66 ft (20 m) in width, surrounded by a low gallery supported on 124 white marble columns. A pavilion projects into the court at each extremity, with filigree walls and a light domed roof. The square is paved with colored tiles and the colonnade with white marble, while the walls are covered 5 ft (1.5 m) up from the ground with blue and yellow tiles, with a border above and below of enameled blue and gold. The columns supporting the roof and gallery are irregularly placed. They are adorned by varieties of foliage, etc.; about each arch there is a large square of stucco arabesques; and over the pillars is another stucco square of filigree work. In the center of the court is the Fountain of Lions, an alabaster basin supported by the figures of twelve lions in white marble, not designed with sculptural accuracy but as symbols of strength, power, and sovereignty. Each hour one lion would produce water from its mouth. At the edge of the great fountain there is a poem written by Ibn Zamrak. This praises the beauty of the fountain and the power of the lions, but it also describes their ingenious hydraulic systems and how they actually worked, which baffled all those who saw them. This is just a simple example of the Muslims' genius at architecture, design and engineering during that time.

The Sala de los Abencerrajes (Hall of the Abencerrages) derives its name from a legend according to which the father of Boabdil, the last sultan of Granada, having invited the chiefs of that line to a banquet, massacred them here. This room is a perfect square, with a lofty dome and trellised windows at its base. The roof is decorated in blue, brown, red and gold, and the columns supporting it spring out into the arch form in a remarkably beautiful manner. Opposite to this hall is the Sala de las dos Hermanas (Hall of the two Sisters), so-called from two white marble slabs laid as part of the pavement. These slabs measure 50 by 22 cm (15 by 7½ in). There is a fountain in the middle of this hall, and the roof — a dome honeycombed with tiny cells, all different, and said to number 5000 — is an example of the "stalactite vaulting" of the Moors.

Of the outlying buildings connected to the Alhambra, the foremost in interest is the Palacio de Generalife or Gineralife (the Muslim Jennat al Arif, "Garden of Arif," or "Garden of the Architect"). This villa dates from the beginning of the 14th century but has been restored several times. The Villa de los Martires (Martyrs' Villa), on the summit of Monte Mauror, commemorates by its name the Christian slaves who were forced to build the Alhambra and confined here in subterranean cells. The Torres Bermejas (Vermilion Towers), also on Monte Mauror, are a well-preserved Moorish fortification, with underground cisterns, stables, and accommodation for a garrison of 200 men. Several Roman tombs were discovered in 1829 and 1857 at the base of Monte Mauror.

Among the other features of the Alhambra are the Sala de la Justicia (Hall of Justice), the Patio del Mexuar (Court of the Council Chamber), the Patio de Daraxa (Court of the Vestibule), and the Peinador de la Reina (Queen's Robing Room), in which there is similar architecture and decoration. The palace and the Upper Alhambra also contain baths, rows of bedrooms and summer rooms, a whispering gallery and labyrinth, and vaulted sepulchres.

The original furniture of the palace is represented by the famous Alhambra vase, one of the very large vases made to stand in niches, an example of Hispano - Moresque ware dating from 1320 and belonging to the first period of Moorish pottery. It is 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) high; the background is white, and the decoration is blue, white and gold.

From 19th century Romantic interpretations until the present day, many buildings and portions of buildings worldwide have been inspired by the Alhambra: there is a Moorish Revival house in Stillwater, Minnesota, which was created and named after the Alhambra. Also, the main portion of the Irvine Spectrum Center in Irvine, California, is a postmodern version of the Court of the Lions. In Portugal, the Ismaili Centre in Lisbon also takes influence from the Alhambra, as does the Arab Room in the Palacio da Bolsa in Porto.