<Back to Index>

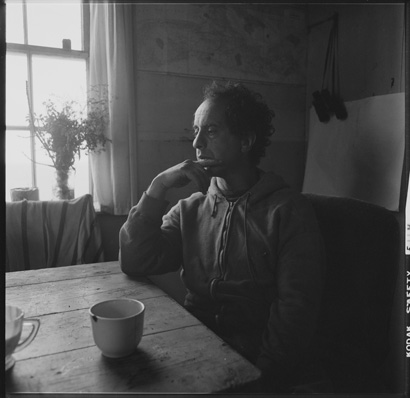

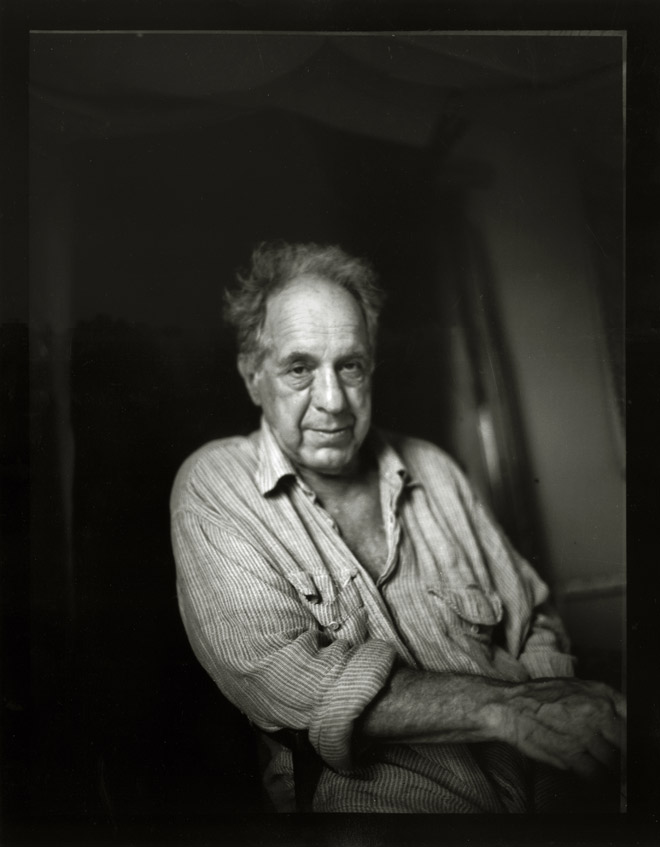

- Photographer Robert Frank, 1924

PAGE SPONSOR

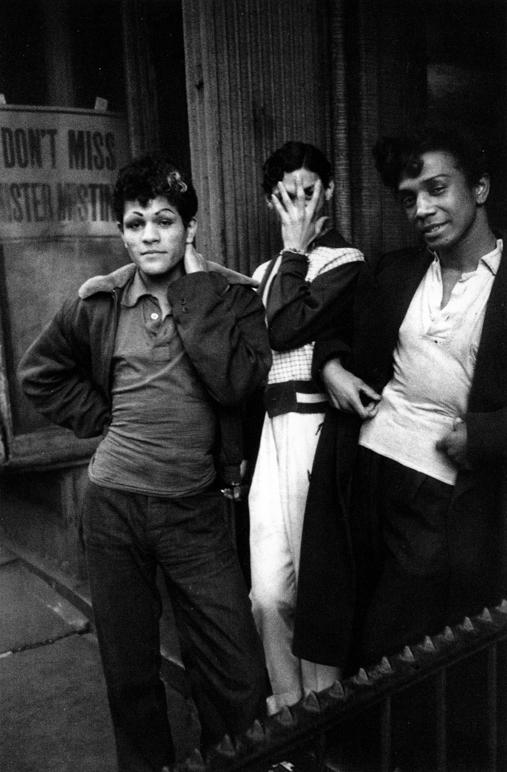

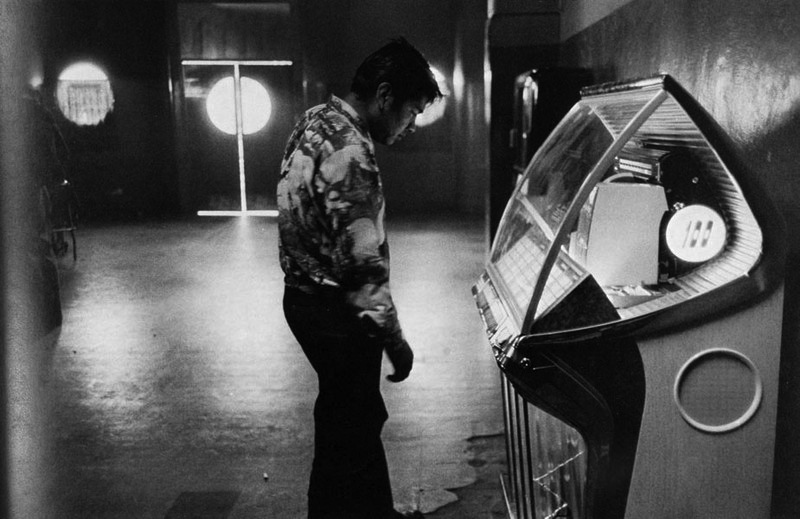

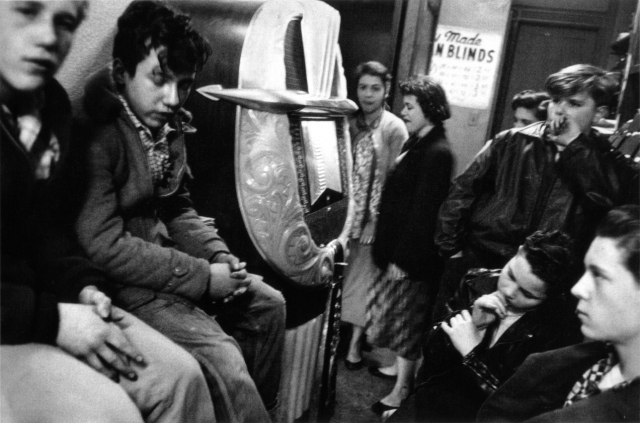

Robert Frank (November 9, 1924 - September 9, 2019) was an important figure in American photography and film. His most notable work, the 1958 photobook titled The Americans, was influential, and earned Frank comparisons to a modern-day de Tocqueville for his fresh and skeptical outsider's view of American society. Frank later expanded into film and video and experimented with manipulating photographs and photomontage.

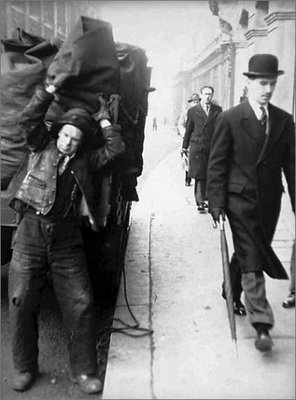

Frank was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Switzerland. His mother, Rosa, was Swiss, but his father, Hermann, had become stateless after World War I and had to apply for the Swiss citizenship of Frank and his older brother, Manfred. Though Frank and his family remained safe in Switzerland during World War II, the threat of Nazism nonetheless affected his understanding of oppression. He turned to photography, in part as a means to escape the confines of his business oriented family and home, and trained under a few photographers and graphic designers before he created his first hand - made book of photographs, 40 Fotos, in 1946. Frank emigrated to the United States in 1947, and secured a job in New York City as a fashion photographer for Harper's Bazaar. He soon left to travel in South America and Europe. He created another hand - made book of photographs that he shot in Peru, and returned to the U.S. in 1950. That year was momentous for Frank, who, after meeting Edward Steichen, participated in the group show 51 American Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); he also married fellow artist Mary Frank née Mary Lockspeiser, with whom he had two children, Andrea and Pablo.

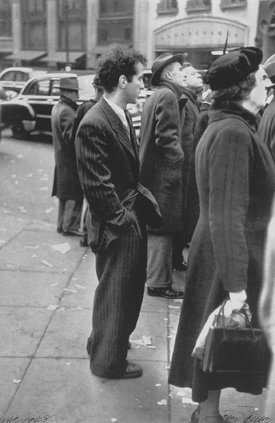

Though he was initially optimistic about United States society and culture, Frank's perspective quickly changed as he confronted the fast pace of American life and what he saw as an overemphasis on money. He now saw America as an often bleak and lonely place, a perspective that became evident in his later photography. Frank's own dissatisfaction with the control that editors exercised over his work also undoubtedly colored his experience. He continued to travel, moving his family briefly to Paris. In 1953, he returned to New York and continued to work as a freelance photojournalist for magazines including McCall's, Vogue and Fortune. Associating with other contemporary photographers such as Saul Leiter and Diane Arbus, he helped form what Jane Livingston has termed The New York School of photographers during the 1940s and 1950s.

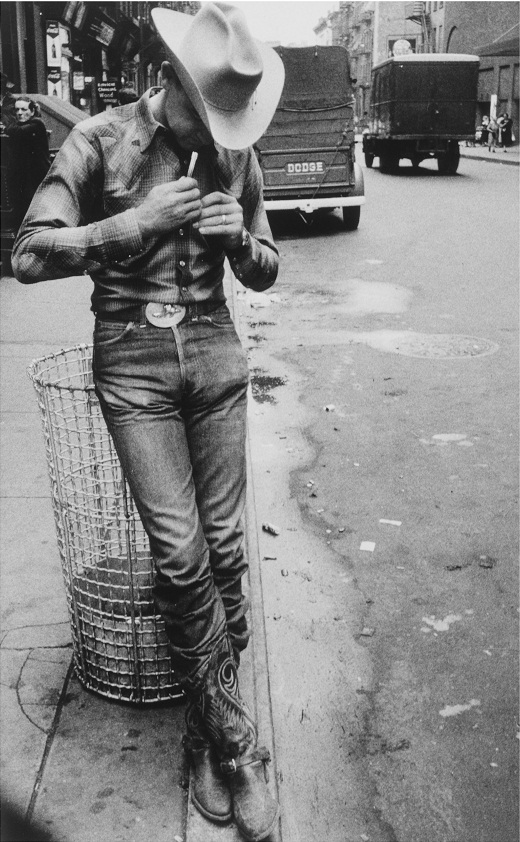

With the aid of his major artistic influence, the photographer Walker Evans, Frank secured a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1955 to travel across the United States and photograph all strata of its society. Cities he visited included Detroit and Dearborn, Michigan; Savannah, Georgia; Miami Beach and St. Petersburg, Florida; New Orleans, Louisiana; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles, California; Reno, Nevada; Salt Lake City, Utah; Butte, Montana; and Chicago, Illinois. He took his family along with him for part of his series of road trips over the next two years, during which time he took 28,000 shots. Only 83 of those were finally selected by him for publication in The Americans. Frank's journey was not without incident. He later recalled the anti - Semitism to which he was subject in a small Arkansas town.

“I remember the guy [policeman] took me into the police station, and he sat there and put his feet on the table. It came out that I was Jewish because I had a letter from the Guggenheim Foundation. They really were primitive.” He was told by the sheriff, “Well, we have to get somebody who speaks Yiddish. They wanted to make a thing out of it. It was the only time it happened on the trip. They put me in jail. It was scary. Nobody knew I was there.”

Elsewhere in the South, he was told by a sheriff that he had "an hour to leave town."

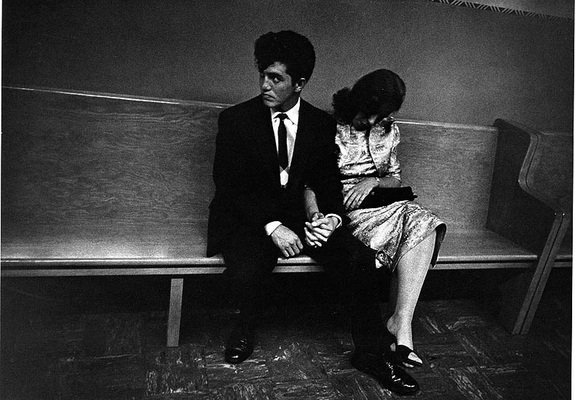

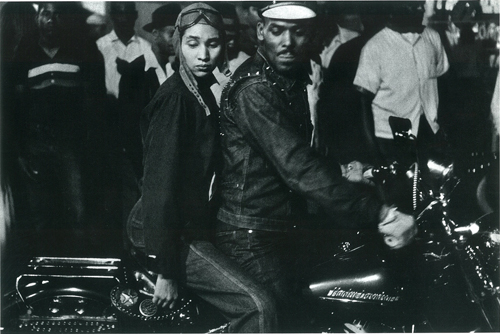

Shortly after returning to New York in 1957, Frank met Beat writer Jack Kerouac on the sidewalk outside a party and showed him the photographs from his travels. Kerouac immediately told Frank "Sure I can write something about these pictures," and he contributed the introduction to the U.S. edition of The Americans. Frank also became lifelong friends with Allen Ginsberg, and was one of the main visual artists to document the Beat subculture, which felt an affinity with Frank's interest in documenting the tensions between the optimism of the 1950s and the realities of class and racial differences. The irony that Frank found in the gloss of American culture and wealth over this tension gave his photographs a clear contrast to those of most contemporary American photojournalists, as did his use of unusual focus, low lighting and cropping that deviated from accepted photographic techniques.

This divergence from contemporary photographic standards gave Frank difficulty at first in securing an American publisher. Les Américains was first published in 1958 by Robert Delpire in Paris, and finally in 1959 in the United States by Grove Press, where it initially received substantial criticism. Popular Photography, for one, derided his images as "meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness." Though sales were also poor at first, the fact that the introduction was by the popular Kerouac helped it reach a larger audience. Over time and through its inspiration of later artists, The Americans became a seminal work in American photography and art history, and is the work with which Frank is most clearly identified. In 1961, Frank received his first individual show, entitled Robert Frank: Photographer, at the Art Institute of Chicago. He also showed at MoMA in New York in 1962.

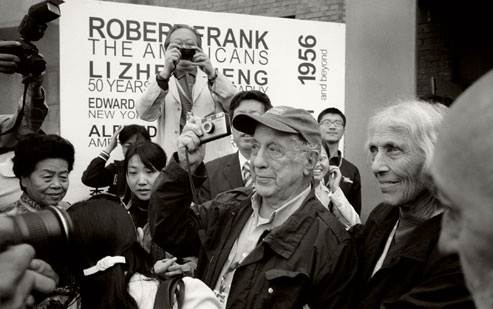

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the first publication of The Americans, a new edition was released worldwide on May 30, 2008. Robert Frank discussed with his publisher, Gerhard Steidl, the idea of producing a new edition using modern scanning and the finest tritone printing. The starting point was to bring original prints from New York to Göttingen, Germany, where Steidl is based. In July 2007, Frank visited Göttingen. A new format for the book was worked out and new typography selected. A new cover was designed and Frank chose the book cloth, foil embossing and the endpaper. Most significantly, as he has done for every edition of The Americans, Frank changed the cropping of many of the photographs, usually cropping less. Two images were changed completely from the original 1958 and 1959 editions. A celebratory exhibit of The Americans was displayed in 2009 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The second section of the four - section, 2009, SFMOMA exhibition displays Frank’s original application to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial (which funded the primary work on the Americans project), along with vintage contact sheets, letters to photographer Walker Evans and author Jack Kerouac, and two early manuscript versions of Kerouac’s introduction to the book. Also exhibited are three collages (made from more than 115 original rough work prints) that were assembled under Frank’s supervision in 2007 and 2008, revealing his intended themes as well as his first rounds of image selection.

By the time The Americans was published in the United States, Frank had moved away from photography to concentrate on film making. Among his films was the 1959 Pull My Daisy, which was written and narrated by Kerouac and starred Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and others from the Beat circle. The Beats emphasized spontaneity, and the film conveyed the quality of having been thrown together or even improvised. Pull My Daisy was accordingly praised for years as an improvisational masterpiece, until Frank's co-director, Alfred Leslie, revealed in a November 28, 1968 article in the Village Voice that the film was actually carefully planned, rehearsed and directed by him and Frank, who shot the film with professional lighting.

In 1960, Frank was staying in Pop artist George Segal's basement while filming Sin of Jesus with a grant from Walter K. Gutman. Isaac Babel's story was transformed to center on a woman working on a chicken farm in New Jersey. It was originally supposed to be filmed in six weeks in and around New Brunswick, but Frank ended up shooting for six months.

His 1972 documentary of the Rolling Stones, Cocksucker Blues, is arguably his best known film. The film shows the Stones while on their '72 tour, engaging in heavy drug use and group sex. Perhaps more disturbing to the Stones when they saw the finished product, however, was the degree to which Frank faithfully captured the loneliness and despair of life on the road. Mick Jagger reportedly told Frank, "It's a fucking good film, Robert, but if it shows in America we'll never be allowed in the country again." The Stones sued to prevent the film's release, and it was disputed whether Frank as the artist or the Stones as those who hired the artist actually owned the copyright. A court order resolved this with Solomonic wisdom by restricting the film to being shown no more than five times per year and only in the presence of Frank. Frank's photography also appeared on the cover of the Rolling Stones' album Exile on Main St..

Other films by Robert Frank include Me and My Brother (film), "Sin of Jesus", "Keep Busy" and Candy Mountain which he co-directed with Rudy Wurlitzer.

Though Frank continued to be interested in film and video, he returned to still images in the 1970s, publishing his second photographic book, The Lines of My Hand, in 1972. This work has been described as a "visual autobiography", and consists largely of personal photographs. However, he largely gave up "straight" photography to instead create narratives out of constructed images and collages, incorporating words and multiple frames of images that were directly scratched and distorted on the negatives. None of this later work has achieved an impact comparable to that of The Americans. As some critics have pointed out, this is perhaps because Frank began playing with constructed images more than a decade after Robert Rauschenberg introduced his silkscreen composites — in contrast to The Americans, Frank's later images simply were not beyond the pale of accepted technique and practice by that time.

Frank and Mary separated in 1969. He remarried, to sculptor June Leaf, and in 1971, moved to the community of Mabou, Nova Scotia in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia in Canada. In 1974, tragedy struck when his daughter, Andrea, was killed in a plane crash in Tikal, Guatemala. Also around this time, his son, Pablo, was first hospitalized and diagnosed with schizophrenia. Much of Frank's subsequent work has dealt with the impact of the loss of both his daughter and subsequently his son, who died in an Allentown, Pennsylvania hospital in 1994. In 1995, he founded the Andrea Frank Foundation, which provides grants to artists.

Since his move to Nova Scotia, Canada, Frank has divided his time between his home there in a former fisherman's shack on the coast, and his Bleecker Street loft in New York. He has acquired a reputation for being a recluse (particularly since the death of Andrea), declining most interviews and public appearances. He has continued to accept eclectic assignments, however, such as photographing the 1984 Democratic National Convention, and directing music videos for artists such as New Order ("Run") and Patti Smith ("Summer Cannibals"). Frank continues to produce both films and still images, and has helped organize several retrospectives of his art. In 1994, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC presented the most comprehensive retrospective of Frank's work to date, entitled Moving Out. Frank was awarded the prestigious Hasselblad Award for photography in 1996. His 1997 award exhibition at the Hasselblad Center in Goteborg, Sweden was entitled Flamingo, as was the accompanying published catalog.

"When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice." Robert Frank, Life (26 November 1951)

"Quality doesn't mean deep blacks and whatever tonal range. That's not quality, that's a kind of quality. The pictures of Robert Frank might strike someone as being sloppy - the tone range isn't right and things like that - but they're far superior to the pictures of Ansel Adams with regard to quality, because the quality of Ansel Adams, if I may say so, is essentially the quality of a postcard. But the quality of Robert Frank is a quality that has something to do with what he's doing, what his mind is. It's not balancing out the sky to the sand and so forth. It's got to do with intention." (Elliott Erwitt) in James Danziger and Barnaby Conrad, 'Interviews with Master Photographers', 1977