<Back to Index>

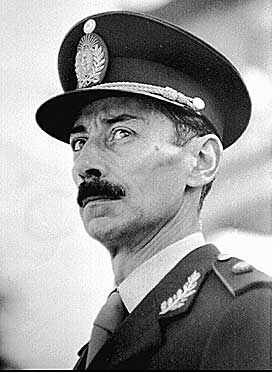

- Dictator of Argentina Jorge Rafael Videla, 1925

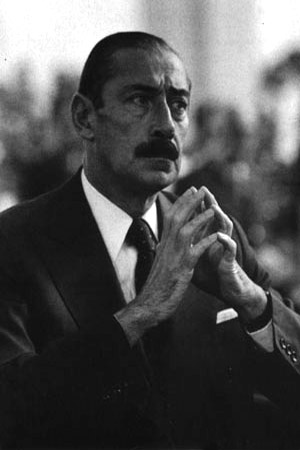

- Dictator of Argentina Roberto Eduardo Viola Redondo, 1924

PAGE SPONSOR

Jorge Rafael Videla (2 August 1925 - 17 May 2013) was a former senior commander in the Argentine Army who was the de facto President of Argentina from 1976 to 1981. He came to power in a coup d'état that deposed Isabel Martínez de Perón. After the return of a representative democratic government, he was prosecuted for large scale human rights abuses and crimes against humanity that took place under his rule, including kidnappings or forced disappearance, widespread torture and extrajudicial murder of activists, political opponents (either real, suspected or alleged) as well as their families, at secret concentration camps. Justice Minister Ricardo Gil Lavedra, who formed part of the 1985 tribunal judging the military crimes committed during the Dirty War would later go on record saying that "I sincerely believe that the majority of the victims of the illegal repression were guerrilla militants". Some 10,000 of the disappeared were guerrillas of the Montoneros (MPM), and the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP). The accusations also included the theft of many babies born during the captivity of their mothers at the illegal detention centers. He was under house arrest until 10 October 2008, when he was sent to a military prison. On 5 July 2010, Videla took full responsibility for his army's actions during his rule. "I accept the responsibility as the highest military authority during the internal war. My subordinates followed my orders," he told an Argentine court. On 22 December 2010, Videla was sentenced to life in a civilian prison for the deaths of 31 prisoners following his coup d'état. On 5 July 2012, Videla was sentenced to 50 years in prison for the systematic kidnapping of children during his tenure.

Jorge Rafael Videla was born on 2 August 1925, in the city of Mercedes, the third of five sons of Colonel Rafael Eugenio Videla (1888 - 1952) and María Olga Redondo Ojea (1897 - 1987). He was christened in honor of two older twin brothers who had died of measles in 1923. Videla's family was an old and prominent one in San Luis Province, and many of his ancestors had held high public offices. His grandfather Jacinto had been governor of San Luis between 1891 and 1893, and his great - great - grandfather Blas Videla had fought in the South American wars of independence and had later been a leader of the Unitarian Party in San Luis.

In 1948 Jorge Videla married Alicia Raquel Hartridge, daughter of Samuel Alejandro Hartridge, an Anglo - Argentine professor of physics and Argentine ambassador to Turkey. They had seven children: María Cristina (1949), Jorge Horacio (1950), Alejandro Eugenio (1951 - 1971), María Isabel (1958), Pedro Ignacio (1966), Fernando Gabriel (1961) and Rafael Patricio (1953). Two of these, Rafael Patricio and Fernando Gabriel, joined the Argentine Army.

Videla joined the National Military College (Colegio Militar de la Nación) on 3 March 1942 and graduated on 21 December 1944 with the rank of second lieutenant.After steady promotion as a junior officer in the infantry, he attended the War College between 1952 and 1954 and graduated as a qualified staff officer. Videla served at the Ministry of Defense from 1958 to 1960 and thereafter he directed the Military Academy until 1962. In 1971, he was promoted to brigadier general and appointed by Alejandro Agustin Lanusse as Director of the National Military College. In late 1973 the head of the Army, Leandro Anaya, appointed Videla as the Chief of Staff of the Army. During July and August 1975, Videla was the Head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Estado Mayor Conjunto) of the Argentine Armed Forces. In August 1975, the President, Isabel Perón, appointed Videla to the Army's senior position, the General Commander of the Army.

Isabel Perón, former Vice President to her husband Juan Perón, had come to the presidency following his death. Her authoritarian administration was unpopular and ineffectual. Videla headed a military coup which deposed her on 24 March 1976. A military junta was formed, made up of himself, representing the Army, Admiral Emilio Massera representing the Navy, and Brigadier General Orlando Ramón Agosti representing the Air Force. Two days after the coup, Videla formally assumed the post of President of Argentina.

The military junta took power during a period of extreme instability, with terrorist attacks from the Marxist groups ERP, the Montoneros, FAL, FAR and FAP, who had gone underground after Juan Perón's death in July 1974, from one side and violent right wing kidnappings, tortures and assassinations from the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, led by José López Rega, Perón's Minister of Social Welfare, and other death squads on the other side. The Baltimore Sun reported at the beginning of 1976 that, "In the jungle - covered mountains of Tucuman, long known as "Argentina's garden," Argentines are fighting Argentines in a Vietnam - style civil war. So far, the outcome is in doubt. But there is no doubt about the seriousness of the combat, which involves 2,000 or so leftist guerrillas and perhaps as many as 10,000 soldiers." In late 1974 the ERP set up a rural front in Tucumán province and the Argentine Army deployed its 5th Mountain Brigade in counterinsurgency operations in the province. In early 1976 the mountain brigade was reinforced in the form of the crack 4th Airborne Infantry Brigade that had until then been withheld guarding strategic points in the city of Córdoba against ERP guerrillas and militants that had staged a massive armed uprising in the last week of August 1975 that had cost the lives of at least five policemen.

The members of the junta took advantage of the guerrilla threat to authorize the coup and naming the period in government as the "National Reorganization Process". In all, 293 servicemen and policemen were killed in left wing terrorist incidents in 1975 and 1976. Videla himself narrowly escaped three Montoneros and ERP assassination attempts between February 1976 and April 1977.

According to estimates, at least 9,000 and perhaps up to 30,000 Argentinians were subjected to forced disappearance (desaparecidos) and most likely killed; many were illegally detained and tortured, and others went into exile. Terence Roehrig, who wrote The prosecution of former military leaders in newly democratic nations: The cases of Argentina, Greece, and South Korea (2001) estimates that of the disappeared "at least 10,000 were involved in various ways with the guerrillas". In the book Disposición Final by Argentine journalist Ceferino Reato, Videla confirms for the first time that between 1976 and 1983, 8.000 argentinians have been murdered by his regime. The bodies were hidden or destroyed to prevent protests at home and abroad. Some 11,000 Argentines have applied for and received up to US$200,000 as monetary compensation from the state for the loss of loved ones during the military dictatorship. The Asamblea por los Derechos Humanos (APDH or Assembly for Human Rights) believes that 12,261 people were killed or disappeared during the "National Reorganization Process". Politically, all legislative power was concentrated in the hands of Videla's nine man junta, and every single important position in the national government was filled with loyal military officers.

During Videla's regime, Argentina rejected the binding Report and decision of the Court of Arbitration over the Beagle conflict at the southern tip of South America and started Operation Soberanía in order to invade the islands. In 1978, however, Pope John Paul II opened a mediation process. His representative, Antonio Samoré, successfully prevented full scale war.

The conflict was not completely resolved until after Videla's time as president. Once the democratic rule was restored in 1983, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina (Tratado de Paz y Amistad), which acknowledged Chilean sovereignty over the islands, was signed and ratified by popular referendum.

Videla largely left economic policies in the hands of Minister José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, who adopted a free trade and deregulatory economic policy. During his tenure, the foreign debt increased fourfold, and disparities between the upper and lower classes became much more pronounced, ending in a tenfold devaluation and one of the worst financial crisis in Argentine history.

One of Videla's greatest challenges was his image abroad. He attributed criticism over human rights to an anti - Argentine campaign.

On 19 May 1976, Videla attended a luncheon with a group of Argentine intellectuals, including Ernesto Sábato, Jorge Luis Borges, Horacio Esteban Ratti (president of the Argentine Writers Society) and Father Leonardo Castellani. The latter expressed to Videla his concern regarding the disappearance of another writer, Haroldo Conti. Borges and Sábato both praised the military regime after this meeting.

On 30 April 1977, Azucena Villaflor, along with 13 other women, started demonstrations on the Plaza de Mayo, in front of the Casa Rosada presidential palace, demanding to be told the whereabouts of their disappeared children; they would become known as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Madres de Plaza de Mayo).

During a human rights investigation in September 1979, the Inter - American Commission on Human Rights denounced Videla's government, citing many disappearances and instances of abuse. In response, the junta hired the Burson - Marsteller ad agency to formulate a pithy comeback: Los argentinos somos derechos y humanos (Literally, "We Argentines are honest and humane") The slogan was printed on 250,000 bumper stickers and distributed to motorists throughout Buenos Aires to create the appearance of a spontaneous support of pro-junta sentiment, at a cost of approximately $16,117.

Videla used the 1978 FIFA World Cup for political purposes, citing the enthusiasm of the Argentine fans for their eventually victorious football team as evidence of his personal and the junta's popularity.

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, leader of the Peace and Justice Service (Servicio Paz y Justicia, SERPAJ) organization, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980 for exposing many of Argentina's human rights violations to the world at large.

Videla relinquished power to Roberto Viola on 29 March 1981. Democracy was restored in 1983, and Videla was put on trial and found guilty. The tribunal found Videla guilty of numerous homicides, kidnapping, torture, and many other crimes. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and was discharged from the military in 1985.

Videla was imprisoned for only five years. In 1990, President Carlos Menem pardoned Videla together with many other former members of the military regime. Menem also pardoned the leftist guerrilla commanders accused of terrorism. In a televised address to the nation, President Menem said, "I have signed the decrees so we may begin to rebuild the country in peace, in liberty and in justice ... We come from long and cruel confrontations. There was a wound to heal."

Videla briefly returned to prison in 1998 when a judge found him guilty of the kidnapping of babies during the Dirty War, including the child of the desaparecida Silvia Quintela and the disappearances of the commanders of the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), Mario Roberto Santucho and Benito Urteaga. Videla spent 38 days in the old part of the Caseros Prison, and was later transferred to house arrest due to health issues.

Following the election of President Néstor Kirchner in 2003, there was a widespread effort in Argentina to show the illegality of Videla's rule. The government no longer recognized Videla as having been a legal president of the country, and his portrait was removed from the military school. There were also many legal prosecutions of officials associated with the crimes of the regime.

On 6 September 2006, Judge Norberto Oyarbide ruled that the pardon granted by Menem was unconstitutional, opening up the possibility of a trial. But the courts refused to prosecute the crimes of the left wing guerrilla groups that according to Argentina's Center for the Legal Study of Terrorism and its Victims killed or maimed some 13,000 Argentines. On 25 April 2007, a federal court struck down his presidential pardon and restored his human rights abuse convictions. He was put on trial on 2 July 2010 for human rights violations relating to the deaths of 31 prisoners who died under his rule. Three days later, he took full responsibility for his army's actions during his rule, saying, "I accept the responsibility as the highest military authority during the internal war. My subordinates followed my orders." The commander of the Montoneros guerrilla army, Mario Firmenich, dropped a political bombshell during the presidency of Fernando de la Rúa, when in a radio interview in late 2000 from Spain he claimed that "In a country that experienced a civil war, everybody has blood in their hands." On 22 December 2010, the trial ended, and Videla was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. He was ordered to be transferred to a civilian prison immediately after the trial. In handing down the sentence, judge María Elba Martínez said that Videla was "a manifestation of state terrorism." During the trial, Videla had said that "yesterday's enemies are in power and from there, they are trying to establish a Marxist regime" in Argentina.

On 5 July 2012, Videla was sentenced to 50 years in prison for his participation in a scheme to steal babies from parents detained by the military regime. According to the court decision, Videla was an accomplice "in the crimes of theft, retention and hiding of minors, as well as replacing their identities."

Roberto Eduardo Viola Redondo (October 13, 1924 - September 30, 1994) was an Argentine military officer who briefly served as president of Argentina from March 29 to December 11, 1981 during a period of military rule.

Viola appointed Lorenzo Sigaut as finance minister, and it became clear that Sigaut (and his protégé Domingo Cavallo) were looking for ways to reverse some of the economic policies of Videla's minister José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz. Notably, Sigaut abandoned the sliding exchange rate mechanism and devalued the peso, after boasting that "they who gamble on the dollar, will lose". Argentines braced for a recession after the excesses of the plata dulce ("sweet money") years, which destabilized Viola's position.

Viola was also the victim of infighting within the armed forces. After being replaced as Navy chief, Eduardo Massera started looking for a political space to call his own, even enlisting the enforced and unpaid services of political prisoners held in concentration camps by the regime. The mainstream of the Junta's support was strongly opposed to Massera's designs and to any attempt to bring about more "populist" economic policies.

Viola found his maneuvering space greatly reduced, and was ousted by a military coup in December 1981, led by the Commander - in - Chief of the Army, Lieutenant General Leopoldo Galtieri, who soon became President. The official explanation given for the ousting was Viola's alleged health problems. Galtieri swiftly appointed Roberto Alemann as finance minister and presided over the build up and pursuit of the Falklands War.

After the collapse of the military regime and the election of Raúl Alfonsín in 1983, Viola was arrested, judged for human rights violations committed by the military junta during the Dirty War, and sentenced to 17 years in prison. His health deteriorated in prison; Viola was pardoned by Carlos Menem in 1990 together with all junta members. He died in 1994.