<Back to Index>

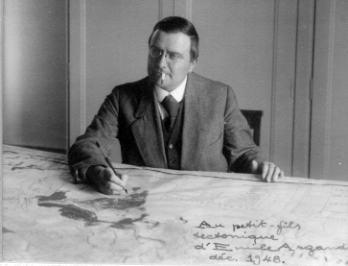

- Geologist Émile Argand, 1879

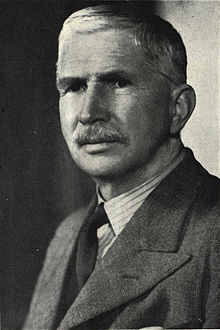

- Geologist Patrick Marshall, 1869

- Physicist Paul Sophus Epstein, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Émile Argand (January 6, 1879 - September 14, 1940) was a Swiss geologist.

He was born in Eaux - Vives near Geneva. He attended vocational school in Geneva, then worked as a draftsman. He studied anatomy in Paris, but gave up medicine to pursue his interest in geology.

He was an early proponent of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift, viewing plate tectonics and continental collisions as the best explanation for the formation of the Alps. He is also noted for his application of the theory of tectonics to the continent of Asia.

He founded the Geological Institute of Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Patrick Marshall (1869 - November 1950) was a geologist who lived in New Zealand. For over forty years he was an outstanding figure among New Zealand scientists, and was well known to geologists in many lands as a versatile and productive investigator. His research was also devoted to zoology. He first used the term "andesite line" in 1912.

Born in 1869, he was the son of the Reverend John Hannath Marshall, M.A., of Sapiston, Suffolk, who, chiefly for reasons of health, moved his family to New Zealand in 1876, and settled at Kaiteriteri in the Nelson District. However, John Marshall died in 1878, and his widow and family returned to England where Patrick Marshall entered school in Bury St. Edmunds.

In 1881 his family returned to New Zealand and resided at Whanganui. Patrick Marshall completed his secondary education at Wanganui Collegiate School before entering Canterbury University College in 1889. In 1892 he was awarded B.A. and B.Sc. degrees with a senior scholarship in geology, which he had studied under Frederick Wollaston Hutton.

In 1893 Marshall completed, with high honours, the M.A. course in geology, working at the University of Otago under George Henry Frederick Ulrich. He completed his first piece of research, a study of the "Tridymite - Trachyte of Lyttelton", which was published in 1894.

Marshall was appointed Lecturer in Natural Science at Lincoln Agricultural College in 1893. His research efforts for a time were devoted chiefly to entomology. Marshall and Hutton were the New Zealand pioneers in the study of Diptera. Marshall took up the study of two very difficult families of the Diptera, the Mycetophilidae and the Cecidomyiidae. He described sixty - one species, which are all still valid except for three names which were preoccupied in other parts of the world, and three synonyms of his own species. This is a remarkable record considering that Marshall worked in isolation, not having access to the literature or to any colleagues who specialized in these families.

Marshall's three papers on the Diptera were published in the Transactions of the New Zealand Institute for 1896 (Vol. 28) together with a fourth, a record of a migrant butterfly. His interests in biology were maintained after he took up geology as a profession, and he presented a paper on the "Effect of the Introduction of Exotic Plants and Animals into New Zealand" to the Fifth Pacific Science Congress in 1933. The paper was published in the Proceedings of this Congress.

In 1896, Marshall became Science Master at Auckland Grammar School and resumed his interests in geological research. He studied the volcanic rocks of that region, completing a thesis, the majority of which is still unpublished, for which he was granted the D.Sc. degree.

In 1901 he became Lecturer - in - charge of the Department of Geology in the University of Otago and was elected Professor of Geology and Mineralogy there in 1908. He remained there for sixteen years, a period of great activity in many directions. His physical strength, which had been displayed by his successes on the football and cricket fields and on the tennis court, was now exercised in field geology and mountaineering.

He was a successful teacher, active in University administration, both in the University of Otago and in the University of New Zealand, of the Senate of which he was for some years a member. His list of publications during the period contains over fifty titles. They included a book on the Geography of New Zealand (1905, revised 1911), the Geology of New Zealand (1912), and the portions of the Handbuch der Regionalen Geologie dealing with New Zealand and the adjacent Islands, and with Oceania (1912). He was extremely active in research. His accounts of the Geology of the Dunedin District (1906) and "The Sequence of Lavas at North Head, Otago Harbour" (1914), which involved a great amount of field work, and petrographical and chemical study, are among the most notable of his many papers. He also published many other papers on the igneous rocks and other features of New Zealand geology in both the South and North Islands. He studied the volcanic rocks of the south - western Pacific, and on this ground of mutual interest he entered into frequent correspondence and later personal association with Professor Antoine Lacroix, and was in 1938 elected a Correspondent de l'Academie des Sciences Coloniales.

He was an active member of what is now the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, ad presented papers before it on the distribution of the igneous rocks in New Zealand (1907), Ocean Contours and Earth Movements in the South - West Pacific (1909), and his Presidential Address to the Geological Section on the structural boundaries of the south - western Pacific (1911) which were shown to be related to the line separating the regions wherein andesitic lavas occur from those wherein there are basic alkaline lavas. This concept was crystallized in his use of the term "andesite line" for the structural boundary of the western half of the Pacific basin in his account of the Geology of Oceania (1912), a term which has come into very general use, though an alternative term, "the Marshall line" has also been used with the same significance. The many problems, geophysical, geological and biological arising from a consideration of the natural history of the Pacific were often in Marshall's mind, and formed the subjects of his Presidential Address to the Geographical Section of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science in 1932, and that given by him as President of the whole Association in 1946.

The preparation of his books on the Geology of New Zealand must have brought very vividly before him the unsatisfactory and to some extent contradictory conceptions regarding the stratigraphy of New Zealand during the opening decade of this century, and he devoted much effort towards the study of the sedimentary succession and molluscan faunas of the Tertiary and Cretaceous rocks, on which he wrote a number of papers, several of them in collaboration with malacologist Robert C. Murdoch. The most important of these papers was his elaborate study of the Cretaceous ammonites of New Zealand (1926), in part written by him while in the British Museum of Natural History. In this paper the Indo - Pacific affinities of the New Zealand forms are discussed. In connection with the Geological Survey he wrote the portions of the Dun Mountain Bulletin (No. 12, published 1912) dealing with Mesozoic stratigraphy and igneous rocks, also the Tuapeka Bulletin (No. 19, published 1918).

Leaving the University of Otago in 1917, he became headmaster of his old school, Wanganui Collegiate, and after retiring several years later he devoted himself for a time to geological research in the Pacific Islands and elsewhere, dealing with their petrology and the features of coral reefs.

In 1924 he was appointed Geologist and Petrologist to the Department of Public Works, where in addition to his general consultative work, he carried out several major lines of research resulting in important publications, a study of special local interest on the building stones of New Zealand (1929) and two of more widespread theoretical importance. In his investigation of the Wearing of Beach Gravels and Beach Gravels and Sands (1928, 1929), carried out both in the field and experimentally, he considered the change in the size and form of the pebbles and the amount and nature of the fine - grained or even colloidal material produced during the processes of attrition, impact and grinding, and in so doing threw much light on the conditions of origin of littoral and off - shore sediments. He also made (1935) elaborate studies of the rocks of rhyolitic composition which are widespread in the center of the North Island of New Zealand and were originally though to be flows and tuffs. He concluded that they were largely composed of particles which had been explosively erupted and had emitted incandescent gases until they had become on cooling agglutinated into coherent rock - masses often showing marked columnar jointing. This mode of origin is comparable with that of the material derived from nuées ardentes (French for "burning cloud", synonymous with pyroclastic flow) of Katmaian eruptions. The occurrence of rocks of like origin is becoming recognized in regions around the Pacific, and the term "ignimbrite" suggested for them by Marshall is tending to replace the term "welded tuffs" which was often assigned to them.

In later years Marshall was greatly interested in the occurrence of orbicular granites in New Zealand, and gave a number of excellent polished specimens of these to geological museums, but published little thereon. He was active in the study of zeolitic minerals, believed by him to be of primary origin, occurring in volcanic rocks, especially in more or less alkaline lavas, and spent much time investigating various methods of recognizing the presence and determining the nature of such minerals by their diagnostic reactions with various solutions principally of silver nitrate. His latest paper (1946), which gave a short account of such studies, was said to be the precursor of a more detailed study then in preparation, which unfortunately was never completed.

Marshall's activities in connection with the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science, his presence at the meetings of the Pacific Science Congress in a number of lands, Japan, Java, and California as well as in Australia and New Zealand, and his presence at two European meetings of the International Geological Conference, as well as his many writings, made him well known to geologists in many parts of the world. His chief services to scientific societies were, however, given to the Royal Society of New Zealand, of which he was President in 1925-6, and from which he received the Hector Memorial Medal in 1915, its first recipient. He also received the Hutton Medal in 1917. As an active member of its Executive Committee for many years he exercised much influence on its policy.

In 1948 he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Science by the University of New Zealand nearly fifty years after he had received the degree by examination on the grounds of his first major research in Geology.

His interest in research was maintained to the last. In a letter written in October, 1950, he referred to the interesting carbonate - bearing magnesian rocks near Milford Sound, which he had described in 1904, regretting that he was unable to return to the field and laboratory investigations of their problematical origin. But he died early in November 1950.

Paul Sophus Epstein (Warsaw, Imperial Russia, now Poland, March 20, 1883 - Pasadena, February 8, 1966) was a Russian - American mathematical physicist. He was known for his contributions to the development of quantum mechanics, part of a group that included Lorentz, Einstein, Minkowski, Thomson, Rutherford, Sommerfeld, Röntgen, von Laue, Bohr, de Broglie, Ehrenfest and Schwarzschild.

Paul Epstein's parents, Siegmund Simon Epstein and Sarah Sophia (Lurie) Epstein were of a middle class Jewish family. He said that his mother recognized his potential at four years old and predicted that he would be a mathematician. He went to the Hochschule in Minsk, and from 1901 - 1905 studied mathematics and physics at the Imperial University of Moscow under Pyotr Nikolaevich Lebedev. In 1909 he graduated, and became a Privatdozent at the University of Moscow. In 1910 he went to Munich, Germany, to do research under Arnold Sommerfeld, who was his advisor, and Epstein was granted a Ph.D. on a problem in the theory of diffraction of electromagnetic waves from the Technische Universität München, in 1914. At the outbreak of World War I he was in Munich, and considered an "enemy alien". Thanks to Sommerfeld's intervention he was allowed to stay in Munich as a private citizen, and could continue with his research. By that time Epstein became interested in the quantum theory of atomic structure. In 1916, he published a seminal paper explaining the Stark effect using the Bohr Sommerfeld ("old") quantum theory. After the war he went to Leiden, to become Hendrik Lorentz' and Paul Ehrenfest's assistant. In 1921 he was recruited by Robert Millikan to come to the California Institute of Technology, where he remained for the rest of his career. In 1922 he published 3 papers on Bohr's quantum mechanics in the Zeitschrift fur Physik and one in the Physical Review. In 1926 he published the paper "The Stark Effect from the Point of View of Schrodinger's Quantum Theory" in the Physical Review, as well as "The New Quantum Theory and the Zeeman Effect" (1926), and "The Magnetic Dipole in Undulatory Mechanics" (1927).

In 1920 Epstein calculated the effect of Polflucht as a possible causing force of Wegeners continental drift. His value was about 10-6 of the gravitational force. Some years later other geophysicists could show that the Polflucht force is far too weak to cause plate tectonics. The toughness of the sublayers of the Earth's crust is much stronger than assumed by Epstein.

In 1930 he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. In 1930, Epstein married Alice Emelie Ryckman, and the couple had a daughter Sari (Mittelbach). After World War II, concerned that some young American intellectuals were becoming attracted to communism, he joined the American Committee of the Congress for Cultural Freedom and in 1951 he served as on of the three US delegates to the seminar the Congress held in Strasbourg.

As well as quantum theory, Epstein also published papers in other fields. Examples include ""Zur Theorie des Radiometers" (1929), "Reflection of Waves in an Inhomogeneous Absorbing Medium" (1930) and "On the Air Resistance of Projectiles" (1931). Other subjects that he worked on were the settling of gases in the atmosphere, the theory of vibrations of shells and plates and the absorption of sound in fogs and suspensions. He retired as Emeritus Professor at Caltech in 1953 and continued to serve as a consultant for a number of industrial companies. One of the significant reports he wrote during this period was "Theory of Wave Propagation in a Gyromagnetic Medium" (1956).

Epstein had other interests as well. He was very interested in Freudian psychology and was one of the founding members of a Psychoanalytic Study Group (together with Thomas Libbin) that later merged into the Los Angeles Institute for Psychoanalysis. In the 1930s he published two articles in the monthly literary and scientific magazine Reflex - "The Frontiers of Science" and "Uses and Abuses of Nationalism". Although he was not an active Zionist, Epstein served as a member of the American National Society of Friends of the Hebrew University and was very friendly with the prominent Israeli mathematician Abraham Fraenkel. The Epstein Memorial Fund was established through donations from more than fifty of his former students and a bronze bust of Epstein stands in the Physics and Mathematics section of the Millikan library at Caltech.