<Back to Index>

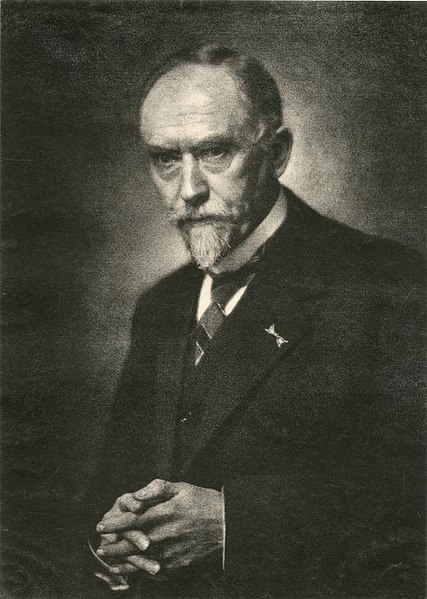

- Geologist and Biologist and Explorer Gustaaf Adolf Frederik Molengraaff, 1860

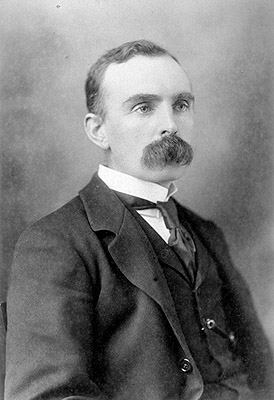

- Geologist and Explorer John Walter Gregory, 1864

PAGE SPONSOR

Gustaaf Adolf Frederik Molengraaff (27 February 1860 Nijmegen - 26 March 1942 Wassenaar) was a Dutch geologist, biologist and explorer. He became an authority on the geology of South Africa and the Dutch East Indies.

Gustaaf Molengraaff studied mathematics and physics at Leiden University. From 1882 he studied at Utrecht University. As a student he made his first journey overseas when he joined the 1884 - 1885 expedition to the Dutch Antilles led by W.F.R. Suringar and K. Martin. He became PhD with a thesis on the geology of Sint Eustatius. He studied crystallography in Munich, where he also took the opportunity to study the geology of the Alps nearby.

In 1888 Molengraaff took a job as a teacher (later as professor) at the University of Amsterdam. Before his assignment courses in geology were given by the chemist J.H. van 't Hoff. During his assignment in Amsterdam Molengraaff traveled to South Africa to study gold deposits (1891) and to Borneo (1894) where he explored large parts of the inland. Teaching at Amsterdam was not to his liking, because there were too little materials and students available.

In 1897 Molengraaff became "state geologist" of the Transvaal Republic. His task was to start the geological survey of the Transvaal. While mapping the Transvaal he discovered the Bushveld complex. In 1900 he got involved in the Second Boer War and had to return to the Netherlands. This gave him time to write a report on the geology of the Transvaal, and travel to Celebes, where he (again) studied gold deposits.

Due to his reputation as a geologist he could return to South Africa in 1901 to work as a geological consultant. One of his assignments was to describe the newly found Cullinan diamond for the Central Bank of South Africa. Meanwhile the Boer War still had his attention. One of his ideas was to give each soldier a small tin identity card, which later became practice in armies around the world.

In 1906 he became professor at Delft University and this time he got enough resources and students to make his work successful. In 1910 - 1911 he led a geological expedition to Timor. His research at Delft was mainly on the material collected during that expedition, and (together with W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht) on the geology of the Netherlands. In 1927 he was a guide of the Shaler Memorial Expedition to South Africa, organized by Harvard University. On the expedition he met Alexander Du Toit, both geologists were among the (at that time rare) supporters of Alfred Wegeners' continental drift theory.

Molengraaff was a close friend of W.F. Gisolf, who named his youngest son after him but died in a Japanese concentration camp.

Molengraaff retired in 1930.

John Walter Gregory, FRS, (27 January 1864 - 2 June 1932) was a British geologist and explorer, known principally for his work on glacial geology and on the geography and geology of Australia and East Africa.

Gregory was born in Bow, London, the only son of a John James Gregory, a wool merchant, and his wife Jane, née Lewis. Gregory was educated at Stepney Grammar School and at 15 became a clerk at wool sales in London. He later took evening classes at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution (now Birkbeck, University of London). He matriculated in 1886, graduated B.Sc. with first - class honours in 1891 and D. Sc. (London) in 1893. In 1887 he was appointed an assistant in the geological department of the Natural History Museum, London.

Gregory remained at the museum until 1900 and was responsible for a Catalogue of the Fossil Bryozoa in three volumes (1896, 1899 and 1909), and a monograph on the Jurassic Corals of Cutch (1900). He obtained leave at various times to travel in Europe, the West Indies, North America and East Africa. The Great Rift Valley (1896), is an interesting account of a journey to Mount Kenya and Lake Baringo made in 1892-3. Gregory was the first to mount a specifically scientific expedition to the mountain. He made some key observations about the geology which still stand. In 1896 he did excellent work as naturalist to Sir Marten Conway's expedition across Spitsbergen. His well known memoir on glacial geology written in collaboration with Edmund J. Garwood belongs to this period.

Gregory's polar and glaciological work led to his brief selection and service in 1900-1 as director of the civilian scientific staff of the Discovery Expedition. The expedition was in planning during this period, and had not yet set sail for Antarctica when Gregory was compelled to resign from his position upon learning that he was outranked by the expedition's commander, Robert Falcon Scott.

The University of Melbourne had created new chair in geology and mineralogy created after the death of Frederick McCoy; on 11 December 1899 Gregory was appointed professor of geology and began his duties in the following February. Gregory was less than five years in Australia but his influence lasted for many years after he left. He succeeded in doing a large amount of work, his teaching was most successful, and he was personally popular. But he came to the university when it was in great financial trouble, there was no laboratory worthy of the name, and the council could not promise any immediate improvement. In 1904 he accepted the chair of geology at Glasgow, and he was back in Great Britain in October of that year. Besides carrying out his professional work he had many other activities during his stay in Australia; during the summer of 1901-2 he had spent his vacation in Central Australia and made a journey around Lake Eyre. An account of this, The Dead Heart of Australia, was published in 1906, dedicated to the geologists of Australia. He also published a popular book on The Foundation of British East Africa (1901), The Austral Geography (1902 and 1903), for school use, and The Geography of Victoria (1903). Another volume, The Climate of Australasia (1904), was expanded from his presidential address to the geographical section of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science which met at Dunedin in January 1904. The Mount Lyell Mining Field, Tasmania, was published in 1905. This does not give a complete impression of Gregory's activities in Australia, for he was director of the Geological Survey of Victoria from 1901, in which year he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, London, and he was able also to find time for university extension lecturing.

Gregory occupied his chair at Glasgow for 25 years and obtained a great reputation both as a teacher and as an administrator. After his retirement in 1929, he was succeeded by Sir Edward Battersby Bailey (Glasgow chair in geology 1929 - 1937). He made several expeditions including one to Cyrenaica in North Africa in 1908, where he showed the same interest in archaeology as in his own subjects; another was to southern Angola in 1912. His journey to Tibet with his son is recorded in To the Alps of Chinese Tibet by J. W. and C. J. Gregory (1923). His other books on geology and geography include:

- Geography: Structural Physical and Compartitive (1908);

- Geology (Scientific Primers Series) (1910);

- Gregory, J. W. (1912). The Making of the Earth. H. Holt and Company;

- The Nature and Origin of Fiords (1913);

- Geology of To-Day (1915);

- Gregory, J. W. (1916). Australia. G. P. Putnam's Sons., in the Cambridge manuals of science and literature;

- Rift Valleys and Geology of East Africa (1921), a continuation of the studies contained in his volume published in 1896;

- The Elements of Economic Geology (1928);

- General Stratigraphy (in collaboration with B. H. Barrett) (1931);

- Dalradian Geology (1931).

He wrote books in other subjects as well, such as The Story of the Road (1931), and he dabbled in eugenics with The Menace of Colour (1925) and Human Migration and the Future (1928).

In January 1932 Gregory went on an expedition to South America to explore and study the volcanic and earthquake centers of the Andes. His boat overturned and he was drowned in the Urubamba River in southern Peru on 2 June 1932.

Gregory married Audrey, daughter of the Rev. Ayrton Chaplin, and had a son and a daughter. He was president of the Geological Society of London from 1928 to 1930, and was awarded many scientific honors including the Bigsby Medal in 1905. Apart from his books he also wrote about 300 papers on geological geographical, and sociological subjects. Gregory was a modest man, sincere, with wide interests. A fast thinker who did an extraordinary amount of work, it is possible that as a geologist he sometimes generalized from insufficient data; his last work Dalradian Geology was adversely reviewed in the Geological Magazine. Nevertheless he was one of the most prominent geologists of his period, widely recognized outside his own country. Most of his books could be read with interest by both men of science and the general public, and as scientist, teacher, traveler, and man of letters, he had much influence on the knowledge of his time.