<Back to Index>

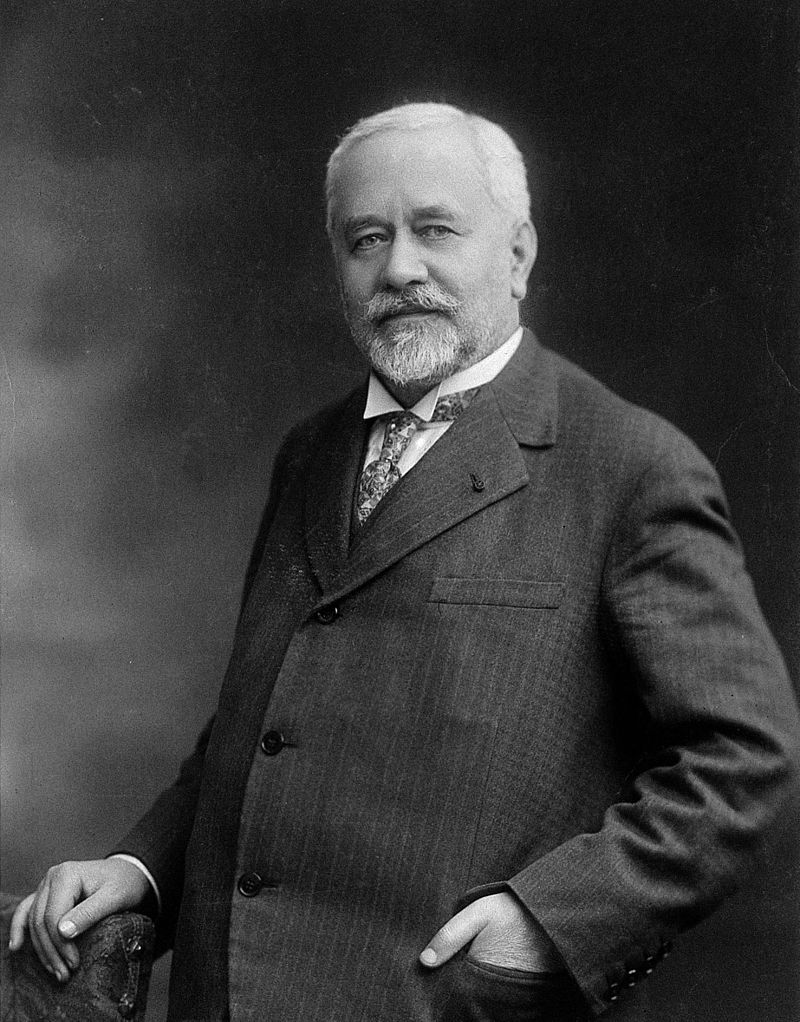

- Physician, Bacteriologist and Immunologist Léon Charles Albert Calmette, 1863

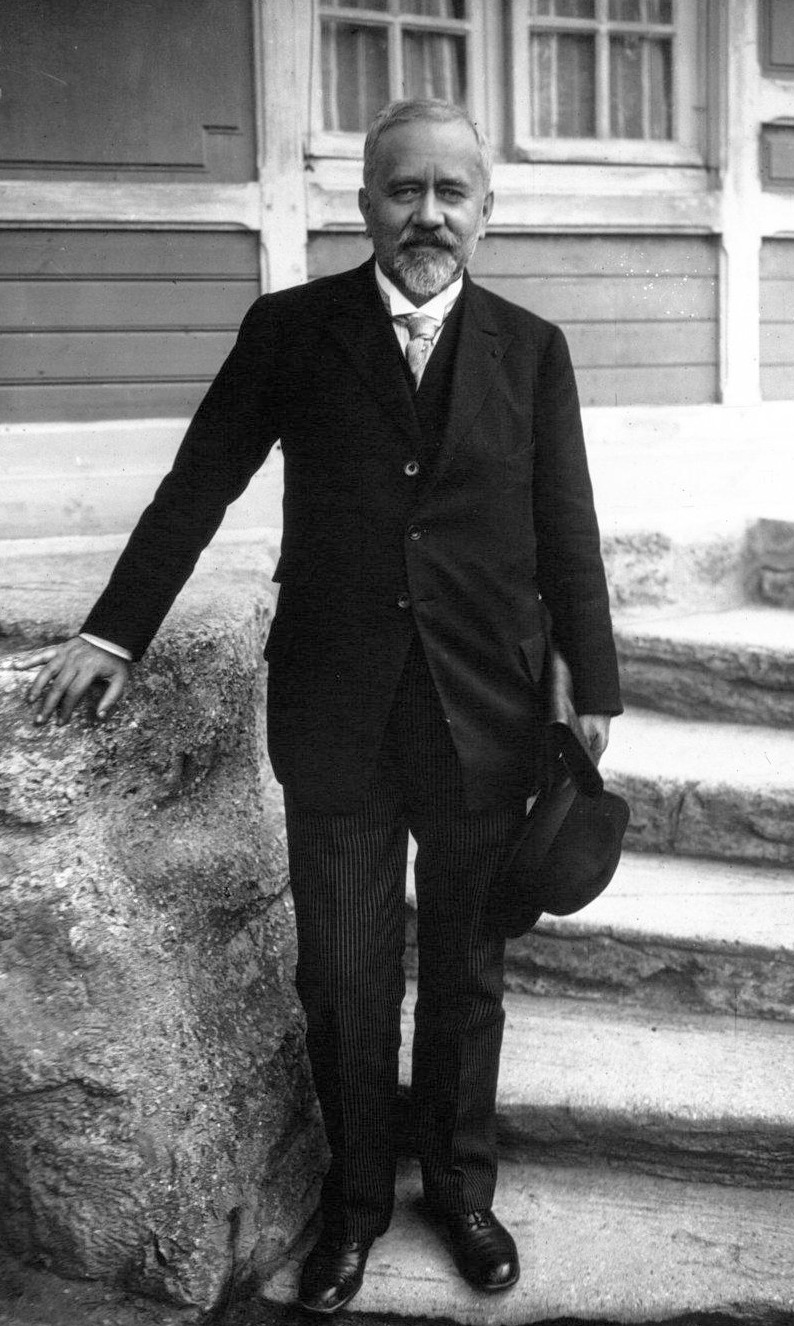

- Physician Otto Ivar Wickman, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Léon Charles Albert Calmette (July 12, 1863 - October 29, 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He discovered the Bacillus Calmette - Guérin, an attenuated form of Mycobacterium used in the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis. He also developed the first antivenin for snake venom, the Calmette's serum.

Calmette was born in Nice, France. He wanted to serve in the Navy and be a physician, so in 1881 he joined the School of Naval Physicians at Brest. He started to serve in 1883 in the Naval Medical Corps in Hong Kong, where he studied malaria and got his doctoral degree in 1886 on this subject. He was then assigned to Saint - Pierre and Miquelon, where he arrived in 1887. After, he served in West Africa, in Gabon and French Congo, where he researched malaria, sleeping sickness and pellagra.

Upon his return to France in 1890, Calmette met Louis Pasteur (1822 - 1895) and Emile Roux (1853 - 1933), who was his professor in a course on bacteriology. He became an associate and was charged by Pasteur to found and direct a branch of the Pasteur Institute at Saigon (French Indochina), in 1891. There, he dedicated himself to the nascent field of toxicology, which had important connections to immunology, and he studied snake and bee venom, plant poisons and curare. He also organized the production of vaccines against smallpox and rabies and carried out research on cholera, and the fermentation of opium and rice.

In 1894, he came back to France again and develop the first antivenoms for snake bites using immune sera from vaccinated horses (Calmette's serum). Work in this field was later taken up by Brazilian physician Vital Brazil, in São Paulo at the Instituto Butantan, who developed several other antivenoms against snakes, scorpions and spiders.

He also took part in the development in the first immune serum against the bubonic plague (black pest), in collaboration with the discoverer of its pathogenic agent, Yersinia pestis, by Alexandre Yersin (1863 - 1943), and went to Portugal to study and to help fight an epidemic at Oporto.

In 1895, Roux entrusted him with the directorship of the Institute's branch at Lille (Institut Pasteur de Lille), where he was to remain for the next 25 years. In 1901, he founded the first antituberculosis dispensary at Lille, and named it after Emile Roux. In 1904, he founded the "Ligue du Nord contre la Tuberculose" (Northern Antituberculosis League), which still exists today.

In 1909, he helped to establish the Institute branch in Algiers (Algeria). In 1918, he accepted the post of assistant director of the Institute in Paris; the following year he was made a member of the Académie Nationale de Médecine.

Calmette's main scientific work, which was to bring him worldwide fame and his name permanently attached to the history of medicine was the attempt to develop a vaccine against tuberculosis, which, at the time, was a giant killer disease. The German microbiologist Robert Koch had discovered, in 1882, that the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis was its pathogenic agent, and Louis Pasteur became interested in it too. In 1906, a veterinarian and immunologist, Camille Guérin, had established that immunity against tuberculosis was associated with the living tubercle bacilli in the blood. Using Pasteur's approach, Calmette investigated how immunity would develop in response to attenuated bovine bacilli injected in animals. This preparation received the name of its two discoverers (Bacillum Calmette - Guérin, or BCG, for short). Attenuation was achieved by cultivating them in a bile - containing substrate, based on idea given by a Norwegian researcher, Kristian Feyer Andvord (1855 - 1934). From 1908 to 1921, Guérin and Calmette strove to produce less and less virulent strains of the bacillus, by transferring them to successive cultures. Finally, in 1921, they used BCG to successfully vaccine newborn infants in the Charité in Paris.

The vaccination program, however, suffered a serious setback when 72 vaccinated children developed tuberculosis in 1930, in Lübeck, Germany, due to a contamination of some batches in Germany. Mass vaccination of children was reinstated in many countries after 1932, when new and safer production techniques were implemented. Notwithstanding, Calmette was deeply shaken by the event, dying one year later, in Paris.

He was the brother of Gaston Calmette (1858 - 1914), the editor of Le Figaro who was murdered in 1914 by Henriette Caillaux, socialite wife of Finance Minister Joseph Caillaux.

Today, his name is one of the few remaining French names in the streets of Ho Chi Minh City (others being Yersin, Rhodes, Pasteur). A new bridge (completed in 2009) is also named "Calmette" connecting district 1 to district 4, also connected to the exit of the new Thu Thiem tunnel connecting the district 1 to the future residential Thu Thiem area in district 2.

Otto Ivar Wickman (10 July 1872, Lund - 20 April 1914, Saltsjöbaden) was a Swedish physician, who discovered in 1907 the epidemic and contagious character of poliomyelitis.

Son of a merchant, Wickman began his medical studies at Lund University in 1890, and passed the state medical examination in 1901 at the Karolinska Institute at Solna near Stockholm. In 1905 he published his doctoral thesis on poliomyelitis “Poliomyelitis acuta” in German, and the doctoral exam in 1906 qualified for the post of a docent for neurology at the Karolinska Institute, besides working as a district physician in the Östermalm district in Stockholm from 1907 to 1909.

As a pupil of pediatrician Karl Oskar Medin, whom he held in high esteem, Wickman predominantly devoted himself to the studies of infantile paralysis (poliomyelitis). Besides his thesis, his 1907 publication Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Heine - Medin’schen Krankheit has been rated as innovative. In the field of neurology he also published several articles. After 1909 Wickman spent more and more time abroad. He worked at the institute of pathology and anatomy in Helsingfors and did psychiatric studies in Paris. Repeatedly having to cope with financial difficulties, he spent his last two years in Breslau and Straßburg, in both places working as an assistant to Adalbert Czerny, the co-founder of modern pediatrics. At the age of 41 he took his life by a shot in the heart in April 1914.

The reasons for his suicide are not known, since Wickman did not leave a farewell letter or any other notes. Colleagues report that the failure of his application for the post of Professor of Pediatrics at the Karolinska Institute, which, until 1914, Medin had held, was a heavy blow for him. When the position was opened for applicants in 1912, Wickman was convinced that he had great chances of becoming successor to his mentor. The commission of the Stockholm Faculty of Medicine, however, preferred one of his two co-applicants in December 1913. On the one hand the members of the commission blamed Wickman for not having shown sufficient diversity in his research work: as many as half of his 22 scientific publications were dealing with polio. On the other hand there was the serious reproach that he had not given a public audit lecture, which was part of the application procedure. He had reported sick because of his "insomnia“ and only submitted a sick note by Professor Czerny, who acknowledged his pupil’s good didactic capacities. There is much reason to assume that Wickman eschewed the public lecture because of his stuttering, which considerably hampered his fluency of speech.

Wickman became known for his achievements in polio research. As a pupil of Karl Oskar Medin and studying the findings of Jakob Heine and Adolf von Strümpell he made detailed clinical and epidemiological studies to establish the hitherto controversial hypothesis that polio can be transferred through physical contact. He was provided with illustrative evidence mainly from the great Swedish epidemic of 1905 with a total of 1,031 recorded cases. Using the example of the small village Trästena in today’s Töreboda he could show that persons with a large contact surface were infected with polio more easily. Within only six weeks 49 children had contracted the disease. First he observed a spreading of the disease along streets and railway lines. After weeks of field trials Wickman succeeded in establishing the fact that the local school played a prominent role in the spread of the disease which henceforth he named Heine - Medin disease.

Wickman published most of his articles and books in German and most of them were quickly translated into English. He came to the result that polio was highly contagious. He suggested taking the so-called abortive and nonparalytic cases as seriously as the grave ones with paralysis, since they were – as he emphasized – instrumental in the spread of the disease. He assumed that the agent could be passed on by presumably healthy persons, and he was the first to find that polio was not exclusively, not even mainly, a disease affecting the central nervous system. Based on his observations he came to the result that the incubation period of polio was three to four days, which had long been disputed but was confirmed in the middle of the twentieth century.

When he coined the term Heine - Medin disease he followed a suggestion of Sigmund Freud, who considered the naming of a disease after its discoverer less problematic than naming it after symptoms or agents. Wickman had found out that Heine’s term Spinale Kinderlähmung (spinal infantile paralysis) and Medin’s work on poliomyelitis only referred to parts of the disease. Wickman’s term, however, was not to assert itself in the long run.

When in 1908, in Vienna, the discovery of the poliovirus by Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper was announced, Wickman did not give up his work as a clinical researcher and pediatrician. Neither did he join the Swedish team of clinical virologists. To him and his findings it did not make much difference, whether the polio agent was a virus or a bacterium.

Wickman’s research work received only little immediate recognition outside the world of medical specialists. The obituary of his colleague Arnold Josefsson after Wickman’s early death is an exception: “The death of Ivar Wickman means the loss of an outstanding personality, not only for our country, but for the medical world as a whole.”

In the mean time, however, he has become recognized as a pioneer of polio research. In 1958 he was posthumously honored by being inducted into the Polio Hall of Fame in Warm Springs, Georgia, USA. Third in line after Heine and Medin, followed by Landsteiner and eleven more polio experts and two laymen (one of them US president Franklin D. Roosevelt), his bronze bust was revealed. Wickman’s classification of the different forms of polio is referred to by the European section of the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “milestone” in polio eradication.

On the other hand, as late as 1971 polio expert and author John Rodman Paul still commented on Wickman’s impact: "Considering the importance of the contributions of Ivar Wickman, I do not believe that his work is fully appreciated today."