<Back to Index>

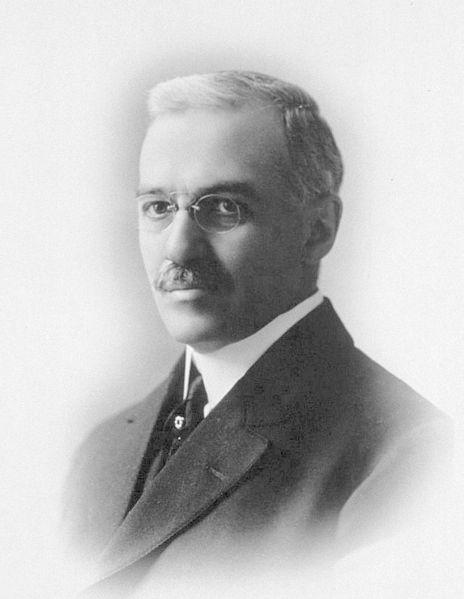

- Bacteriologist William Hallock Park, 1863

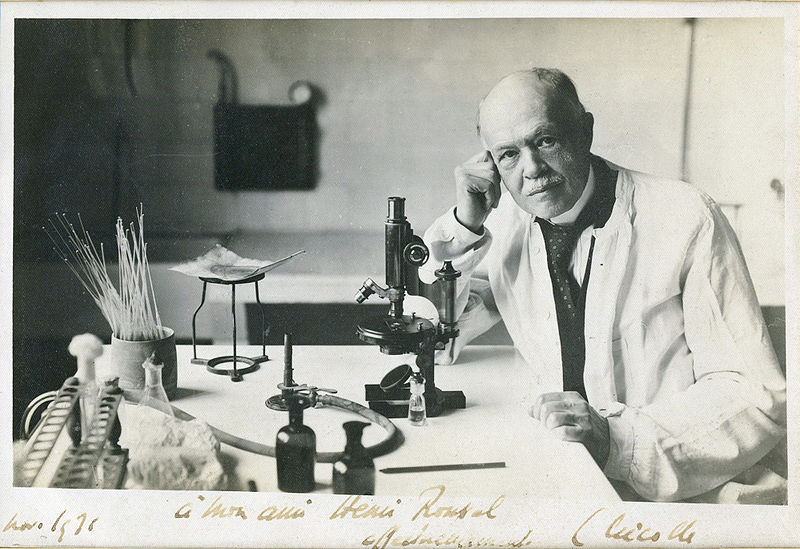

- Bacteriologist Charles Jules Henry Nicolle, 1866

PAGE SPONSOR

William Hallock Park (December 30, 1863 - April 6, 1939) was an American bacteriologist and Laboratory Director, New York City Board of Health, Division of Pathology, Bacteriology, and Disinfection 1893 to 1936

Park was born on December 30, 1863 in New York City.

In June 1883 he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from City College and entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons to study medicine. He studied pathology with Dr. Theophil Mitchell Prudden planning to become a nose and throat specialist. After Park graduated in 1893 he interned at Roosevelt Hospital and had a year of post graduate study in Vienna, Austria. On his return in 1890 Park worked on the bacteriology of diphtheria with Dr. Prudden.

In 1893 Dr Herman M. Biggs, Chief Inspector, New York Board of Health offered Park a position within the municipal laboratories to work to prevent diphtheria. In 1894, Dr Biggs telegraphed Park with the news of the discovery of the diphtheria antitoxin by Roux and Behring and instructed him to begin inoculating horses to produce antitoxin in New York City. The atypical strain of Corynebacterium diphtheriae, most widely used for the production of diphtheria toxin, was discovered by Anna W. Williams who worked for William H. Park.

Highlights of Park's career included the establishment of the first municipal bacteriological diagnostics laboratory in the United States, the application of toxin - antitoxin vaccines to prevent diphtheria, and the publication of the widely used textbook Pathogenic Bacteriology co-authored with Anna Wessels Williams. In 1932 he was awarded the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.

Damaging to his reputation was the attenuated live polio vaccine developed by Maurice Brodie that resulted in vaccine derived cases of polio in children inoculated with this experimental vaccine.

Dr. Park retired as Director of the Research laboratories of the Public Health Department of New York City in September 1936 and died in April 1939.

Charles Jules Henry Nicolle (21 September 1866, Rouen - 28 February 1936, Tunis) was a French bacteriologist who received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his identification of lice as the transmitter of epidemic typhus.

He learned about biology early from his father Eugène Nicolle, a doctor at a Rouen hospital. He was educated at the Lycée Pierre Corneille in Rouen. He received his M.D. in 1893 from the Pasteur Institute. At this point he returned to Rouen, as a member of the Medical Faculty until 1896 and then as Director of the Bacteriological Laboratory.

In 1903 Nicolle became Director of the Pasteur Institute in Tunis, where he did his Nobel Prize winning work on typhus. He was still director of the Institute when he died in 1936.

He also wrote fiction and philosophy through his life, including the books Le Pâtissier de Bellone, Les deux Larrons and Les Contes de Marmouse.

He married Alice Avice in 1895, and had two children, Marcelle (b. 1896) and Pierre (b. 1898).

Nicolle's major accomplishments in bacteriology and parasitology were:

- The discovery of the transmission method of typhus fever;

- The introduction of a vaccination for Malta fever;

- The discovery of the transmission method of tick fever;

- His studies of cancer, scarlet fever, rinderpest, measles, influenza, tuberculosis and trachoma;

- Identification of the parasitic organism Toxoplasma gondii within the tissues of the gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi).

During his life Nicolle wrote a number of non-fiction and bacteriology books, including Le Destin des Maladies infectieuses; La Nature, conception et morale biologiques; Responsabilités de la Médecine and La Destinée humaine.

Nicolle's discovery came about first from his observation that, while epidemic typhus patients were able to infect other patients inside and outside the hospital, and their very clothes seemed to spread the disease, they were no longer infectious when they had had a hot bath and a change of clothes. Once he realized this, he reasoned that it was most likely that lice were the vector for epidemic typhus.

In June 1909 Nicolle tested his theory by infecting a chimpanzee with typhus, retrieving the lice from it, and placing it on a healthy chimpanzee. Within 10 days the second chimpanzee had typhus as well. After repeating his experiment he was sure of it: lice were the carriers.

Further research showed that the major transmission method was not louse bites but excrement: lice infected with typhus turn red and die after a couple of weeks, but in the meantime they excrete a large number of microbes. When a small quantity of this is rubbed on the skin or eye, an infection occurs.

Nicolle surmised that he could make a simple vaccine by crushing up the lice and mixing it with blood serum from recovered patients. He first tried this vaccine on himself, and when he stayed healthy he tried it on a few children (because of their better immune systems), who developed typhus but recovered.

He did not succeed in his effort to develop a practical vaccine. The next step would be taken by Rudolf Weigl in 1930.