<Back to Index>

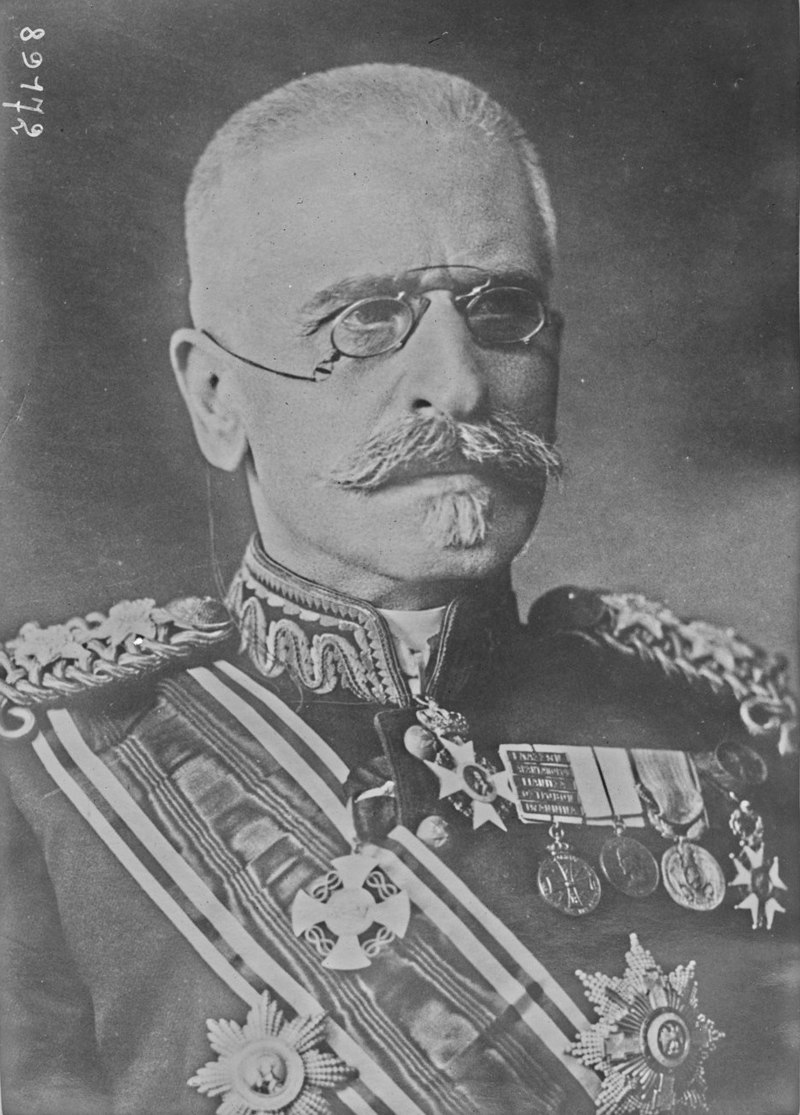

- King of the Hellenes Constantine I (Κωνσταντίνος Α'), 1868

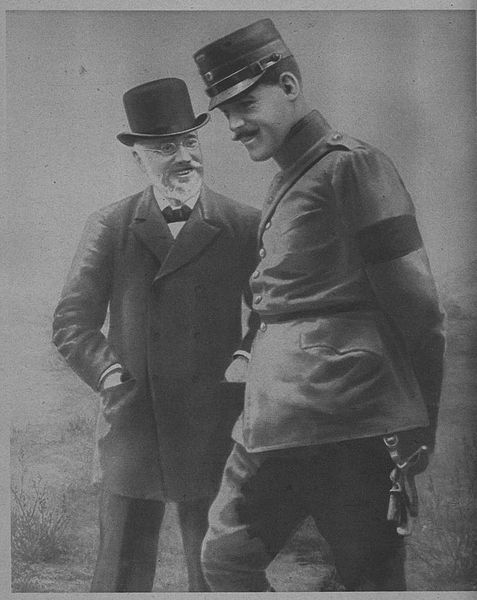

- Lieutenant General of the Hellenic Army and Member of Parliament Panagiotis Danglis (Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής), 1853

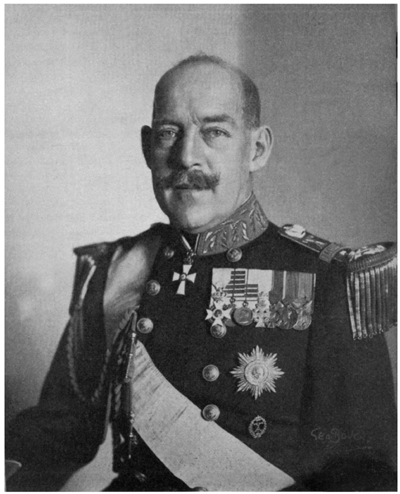

- Admiral of the Hellenic Navy and 1st President of the 2nd Hellenic Republic Pavlos Kountouriotis (Παύλος Κουντουριώτης), 1855

PAGE SPONSOR

Constantine I (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος Αʹ, Βασιλεὺς τῶν Ἑλλήνων, Konstantínos Αʹ, Vasiléfs ton Ellínon; 2 August [O.S. 21 July] 1868 - 11 January 1923) was King of Greece from 1913 to 1917 and from 1920 to 1922. He was commander - in - chief of the Hellenic Army during the unsuccessful Greco - Turkish War of 1897 and led the Greek forces during the successful Balkan Wars of 1912 - 1913, in which Greece won Thessaloniki and doubled in area and population. He succeeded to the throne of Greece on 18 March 1913, following his father's assassination.

His disagreement with Eleftherios Venizelos over whether Greece should enter World War I led to the National Schism. Constantine forced Venizelos to resign twice, but in 1917 he left Greece, after threats of the Entente forces to bombard Athens; his second son, Alexander, became king. After Alexander's death, Venizelos' defeat in the 1920 legislative elections, and a plebiscite in favor of his return, Constantine was reinstated. He abdicated the throne for the second and last time in 1922, when Greece lost the Greco - Turkish War of 1919 - 1922, and was succeeded by his eldest son, George II. Constantine died in exile four months later, in Sicily.

Born on 2 August 1868 in Athens, Constantine was the eldest son of King George I and Queen Olga of Greece. His birth was met with an immense wave of enthusiasm: The new heir apparent to the throne was the first Greek born royal. As the ceremonial cannon on Lycabettus Hill fired the Royal salute, huge crowds gathered outside the Palace shouting what they thought should rightfully be the newborn prince's name: "Constantine". This was not only the name of his maternal grandfather, Grand Duke Konstantin Romanov of Russia, but also the name of the "King who would reconquer Constantinople", the future "Constantine XII, legitimate successor to the Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos", according to popular legend. Upon his birth, he was created Duke of Sparta. This resulted in a heated dispute in Parliament, since the constitution neither allowed nor recognized any titles of nobility for Greek citizens, but the purely titular dignity was eventually awarded. He was inevitably christened "Constantine" (Greek: Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantīnos) on 12 August, and his official style was the Diádochos (Διάδοχος, Crown Prince, literally: "Successor"). An additional nickname adopted mainly by the royalists for Constantine was "the son of the eagle" (ο γιός του αητού). The most prominent university professors of the time were handpicked to tutor the young Crown Prince: Ioannis Pantazidis taught him Greek literature; Vasileios Lakonas mathematics and physics; and Constantine Paparrigopoulos history, infusing the young prince with the principles of the Megali Idea. On 30 October 1882 he enrolled in the Hellenic Military Academy. After graduation he was sent to Berlin for further military education, and served in the German Imperial Guard. Constantine also studied political science and business in Heidelberg and Leipzig. In 1890 he became a Major General, and assumed command of the 3rd Army Headquarters (Γ' Αρχηγείον Στρατού) in Athens.

In January 1895, Constantine caused political turmoil when he ordered army and gendarmerie forces to break up a street protest against tax policy. Constantine had previously addressed the crowd and advised them to submit their grievances to the government. Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis asked the King to recommend that his son avoid such interventions in politics without prior consultation with the government. King George responded that the Crown Prince was, in dispersing protesters, merely obeying military orders, and that his conduct lacked political significance. The incident caused a heated debate in Parliament, and Trikoupis finally resigned as a result. In the following elections Trikoupis was defeated, and the new Prime Minister, Theodoros Deligiannis, seeking to downplay hostility between government and the Palace, regarded the matter closed.

The organization of the first modern Olympics in Athens was another issue which caused a Constantine - Trikoupis confrontation, with Trikoupis opposed to hosting the Games. After Deligiannis' electoral victory over Trikoupis in 1895, those who favored a revival of the Olympic Games, including the Crown Prince, prevailed. Subsequently, Constantine was instrumental in the organization of the 1896 Summer Olympics; according to Pierre de Coubertin, in 1894 "the Crown Prince learned with great pleasure that the Games will be inaugurated in Athens." Coubertin assured that "the King and the Crown Prince will confer their patronage on the holding of these Games." Constantine later conferred more than that; he eagerly assumed the presidency of the 1896 organizing committee. At the Crown Prince's request, wealthy businessman George Averoff agreed to pay approximately one million drachmas to fund the restoration of the Panathinaiko Stadium in white marble.

Constantine was the commander - in - chief of the Greek Army in the Greco - Turkish War of 1897, which ended in a humiliating defeat. In its aftermath, the popularity of the monarchy fell, and calls were raised in the army for reforms and the dismissal of the royal princes, and especially Constantine, from their command posts in the armed forces. The simmering dissent culminated in the Goudi coup in August 1909. In its aftermath, Constantine and his brothers were dismissed from the armed forces, only to be reinstated a few months later by the new Prime Minister, Eleftherios Venizelos, who was keen on gaining the trust of King George. Venizelos was ingenious in his argumentation: "All Greeks are rightly proud to see their sons serve in the army, and so is the King". What was left unsaid was that the royal princes' commands were to be on a very tight leash.

Turkish planning was foreseeing a two - prong Greek attack east and west of the impassable Pindus mountain range, and they accordingly allotted their resources, equally divided, on a defensive posture in order to fortify the approaches to Ioannina, capital of Epirus, and the mountain passes leading from Thessaly to Macedonia. This was a grave error. The war plan by Venizelos and the General Staff called for a rapid advance with overwhelming force towards Thessaloniki with its vitally important harbor. A minute force of little more than a division proper, just enough to forestall a possible Turkish redeployment eastwards, was to be sent west as the "Army of Epirus", while the bulk of the army and artillery would embark on what would later be called "blitzkrieg" tactics against the Turks in the east. In the event the Greek plan worked brilliantly: advancing on foot, the Greeks defeated the Turks soundly twice, and were in Thessaloniki within 4 weeks. The Greek plan for overwhelming attack and speedy advance hinged upon another factor: should the Greek Navy succeed in blockading the Turkish fleet within the Straits, any Turkish reinforcements from Asia would have no way of reaching Europe fast. Turkey would be slow to mobilize, and even when the masses of loyal troops raised in Asia were ready, they could go no further than the outskirts of Istanbul, fighting the Bulgarians in brutal trench warfare. With the Bulgarians directing the bulk of their force towards Constantinople, capture of Thessaloniki would ensure that the railway axis between these two main cities was lost to the Turks, who would then suffer total loss of logistics and supplies and severe impairment of command and control capability. The Turks would be hard placed to recruit locals, as their loyalties would be liable to lie with the Balkan Allies. Ottoman armies in Europe would be quickly cut off and their loss of morale and operational capability would lead them toward a quick surrender.

Previously the Inspector General of the Army, Constantine was appointed commander - in - chief of the Greek "Army of Thessaly" when the First Balkan War broke out in October 1912. He led the Army of Thessaly to victory at Sarantaporos. At this point, his first clash with Venizelos occurred, as Constantine desired to press north, towards Monastir, where the bulk of the Ottoman army lay, and where the Greeks would rendezvous their Serb allies. Venizelos, on the other hand, demanded that the army capture the strategic port city of Thessaloniki, the capital of Macedonia, with extreme haste, so as to prevent its fall to the Bulgarians. The dispute resulted in a heated exchange of telegrams. Venizelos notified Constantine that "... political considerations of the utmost importance dictate that Thessaloniki be taken as soon as possible". After Constantine impudently cabled: "The army will not march on Thessaloniki. My duty calls me towards Monastir, unless you forbid me", Venizelos was forced to pull rank. As Prime Minister and War Minister, he outranked Constantine and his response was famously three - words - long, a crisp military order to be obeyed forthwith: "I forbid you". Constantine was left with no choice but to turn east, and after defeating the Ottoman army at Giannitsa, he accepted the surrender of the city of Thessaloniki and of its Ottoman garrison on 27 October (O.S.), less than 24 hours before the arrival of Bulgarian forces who hoped to capture the city first.

The capture of Thessaloniki against Constantine's whim proved a crucial achievement: The pacts of the Balkan League had provided that in the forthcoming war against the Ottoman Empire, the four Balkan allies would provisionally hold any ground they took from the Turks, without contest from the other allies. Once an armistice was declared, then facts on the ground would be the starting point of negotiations for the final drawing of the new borders in a forthcoming peace treaty. With the vital port firmly in Greek hands, all the other allies could hope for was a customs - free dock in the harbor.

In the meantime, operations in the Epirus front had stalled: Against the rough terrain and Ottoman fortifications at Bizani, the small Greek force could not make any headway. With operations in Macedonia complete, Constantine transferred the bulk of his forces to Epirus, and assumed command. After lengthy preparations, the Greeks broke through the Ottoman defenses in the Battle of Bizani and captured Ioannina and most of Epirus up into what is today southern Albania (Northern Epirus). These victories dispelled the tarnish of the 1897 defeat, and raised Constantine to great popularity with the Greek people.

At that point, tragedy struck: George I was assassinated in Thessaloniki by an anarchist, Alexandros Schinas, on 18 March 1913, and Constantine succeeded to the throne. In the meantime, tensions between the Balkan allies grew, as Bulgaria claimed Greek and Serbian occupied territory. In May, Greece and Serbia concluded a secret defensive pact aimed at Bulgaria. On 16 June, the Bulgarian army attacked their erstwhile allies, but were soon stopped. King Constantine again led the Greek Army in its counterattack in the battles of Kilkis - Lahanas and the Kresna Gorge. He was keen to go for the jugular, Sofia. In the meantime the Bulgarian army has started to disintegrate: beset by defeat in the hands of Greeks and Serbs, they were suddenly faced with a surprising Turkish counterattack with fresh Asian troops finally ready, while the Romanians advanced south, demanding Southern Dobrudja as a compensation to the overreaching Bulgarians. Bulgaria had to sue for peace, agreed to an armistice and entered negotiations in Bucharest. The victories in the second war gave a further boost to Constantine's popularity, with him being widely acclaimed as "Bulgar - slayer", in imitation of the Byzantine emperor Basil II. On the initiative of Prime Minister Venizelos, Constantine was also awarded the rank and baton of a Field Marshal.

The widely held view of Constantine I as a "German sympathiser" owes much to Allied and Venizelist war time propaganda directed against the King. Constantine rebuffed Kaiser Wilhelm who in 1914 pressed him to bring Greece into the war on the side of Austria and Germany. Constantine offended British and French interests by blocking efforts by Prime Minister Venizelos to bring Greece into the war on the side of the Allies. Constantine's insistence on neutrality was based on his judgement that it was the best policy for Greece.

Admiral Mark Kerr, who was Commander - in - Chief of the Royal Hellenic Navy in the early part of World War I and later Commander - in - Chief of the British Adriatic Squadron, wrote in 1920:

"The persecution of King Constantine by the press of the Allied countries, with some few good exceptions, has been one of the most tragic affairs since the Dreyfus case." [Abbott, G.F. (1922) 'Greece and the Allies 1914 - 1922']

Although Venizelos, with British and French support, forced Constantine from the Greek throne in 1917 he remained popular with parts of the Greek people, as shown by the overwhelming vote for his return in the December 1920 plebiscite.

In the aftermath of the victorious Balkan Wars, Greece was in a state of euphoria. Her territory and population had doubled and, under the dual leadership of Constantine and Venizelos, her future seemed bright. This state of affairs was not bound to last long, however. When World War I broke out, Constantine was faced with the difficulty of determining where Greece's support lay. His own sympathies lay with Imperial Germany ruled by his wife's brother, the Kaiser. Sophie, his queen, was popularly thought to support her brother as well, but it seems that she was actually pro-British; like her father the late Kaiser Frederick, Sophie was heavily influenced by her mother, the British born Victoria. Venizelos was fervently pro-Entente, having established excellent rapport with the British and French echelons of power. He also was keenly aware that a maritime country like Greece could not, and should not, antagonize the Entente, the dominant naval powers in the Mediterranean. This latter point at least came across to the king, no matter where his personal sympathies lay. He finally chose a policy of neutrality. The bold, insubordinate general of a few years before now seemed content to risk nothing and would possibly settle for as much after the war was over. Unable to impose unconstitutionally his will upon the lawfully elected government, he chose to neutralize it for the time being.

Constantine's sympathies for Germany were made manifest during the Allies' disastrous landing on Gallipoli. Despite support for Venizelos among the people and his clear majority in Parliament, Constantine opposed Venizelos's increasing support for the Allies. When Bulgaria attacked Serbia, with whom Greece had a treaty of alliance, Venizelos again urged the King to allow Greece's entry into the war, and permitted Entente forces to disembark in Thessaloniki in preparation for a common campaign over the king's objections. After Constantine refused again to support Greece's entry on the side of the Allies, however, Venizelos resigned, and Constantine appointed Alexandros Zaimis in his place, at the head of a short lived coalition government.

In July 1916, arsonists set fire to the forest surrounding the summer palace at Tatoi, in what was popularly seen as a sign of dissatisfaction with the king's policy of neutrality. Although injured in the escape, the king and his family managed to flee to safety. The flames spread quickly in the dry summer heat, and sixteen people were killed. In May and August 1916, Constantine and General Ioannis Metaxas (future dictator) allowed parts of eastern Macedonia to be occupied, without opposition, by the Central Powers.

The country seethed with rage and in August 1916, an Entente supported Venizelist revolt broke out in Thessaloniki. There, Venizelos established a provisional revolutionary government, which declared war on the Central Powers. With civil war apparently imminent, Constantine sought firm German promises of naval, military and economic assistance - without success. Gradually, and with Allied support, Venizelos gained control of half the country - significantly, most of the "New Lands" won during the Balkan Wars. This cemented the "National Schism", a division of Greek society between Venizelists and anti - Venizelist monarchists, which was to have repercussions in Greek politics until past World War II.

Early in 1917, the Venizelist Government of National Defense (based in Thessaloniki) took control of Thessaly. In the face of Venizelist and Anglo - French pressure, King Constantine left the country for Switzerland on 11 June 1917; his second born son Alexander became king in his place. The Allied Powers were opposed to Constantine's firstborn son George becoming King, as he had served in the German army before the war and identified with his father's pro-German policies.

Constantine's younger son, King Alexander, died on 25 October 1920, after a freak accident: he was strolling with his dogs in the royal menagerie, when they attacked a monkey. Rushing to save the poor animal, the king was bitten by the monkey and what seemed like a minor injury turned to septicemia. He died a few days later. The following month Venizelos suffered a surprising defeat in a general election. Greece had at this point been at war for eight continuous years: World War I had come and gone, yet no sign of an enduring peace was near. All young men had been fighting and dying for years, lands lay fallow for lack of hands to cultivate them, and the country, morally exhausted, was at the brink of physical exhaustion. The pro-royalist parties promised peace and prosperity under the victorious Field Marshal of the Balkan Wars, he who knew of the soldier's plight because he had fought next to him and shared his ration. Following a plebiscite in which nearly 99% of votes were cast in favor of his return, Constantine returned as king on 19 December 1920. This caused great dissatisfaction not only to the newly liberated populations in Asia Minor, but also to the Great Powers who opposed the return of Constantine.

Within two years the king's new found popularity was lost again. The inherited ongoing Asia Minor Campaign against Turkey proved disastrous for the Greeks. An ill conceived plan to go for the jugular again, Kemal's new capital of Ankara, deep in barren Anatolia where no Greek lived, succeeded enough only to raise some faint and ill fated hopes. The Turks eventually broke the overstretched Greek front and routed the Greek army through Anatolia to the shore, burning Smyrna. Following an army revolt, Constantine abdicated the throne again on 27 September 1922 and was succeeded by his eldest son, George II.

He spent the last four months of his life in exile in Italy and died in 1923 at Palermo, Sicily. His queen, Sophie of Prussia, was never allowed back in Greece. A life and reign that had started under the brightest of auspices ended in ruin.

Panagiotis Danglis (Greek: Παναγιώτης Δαγκλής, 1853 - 1924) was a Greek general of the Hellenic Army and a politician.

Born into an Arvanite family in Agrinio in 1853, he graduated from the Scholi Evelpidon Officer Academy in 1878 as a Second Lieutenant of Artillery, and later extended his studies for another year in Belgium. Upon his return, as Captain, he was appointed adjutant to the 1884 - 1887 French military mission, which had been tasked with modernizing the Greek Army. He was a recognized expert in artillery, teaching at the Army Academy and inventing the Schneider - Dangli Gun in 1893. During the Greco - Turkish War of 1897 he served as chief of staff of I Brigade in the Epirus sector. As a Lieutenant Colonel, he was transferred to the General Staff Corps in 1904.

Promoted to Colonel in 1907, he participated in the latter stages of the Macedonian Struggle, supervising operations in the Salonica area, under the nom de guerre of Parmenion. Promoted to Major General in 1911, he was appointed head of the Army General Staff in August 1912, partly because of his abilities, but also as a balance to the more royalist and Germanophile staff officers like Ioannis Metaxas. During 1908-9 he headed the Macedonian Committee and the Panhellenic Organization. During the First Balkan War, he served as chief of staff to Crown Prince Constantine's Army of Thessaly until November 1912, when he became a member of the Greek delegation in the London Peace Conference. In March 1913 he was promoted to Lieutenant General and placed in command of the Epirus Army Corps.

In late 1914, he left the army and went into politics, joining the Liberal Party of Eleftherios Venizelos in 1915 and elected as an MP for Epirus representing Ioannina. He became Minister for War and supported Venizelos during his struggle against King Constantine in 1916, joining his Triumvirate, the "Provisional Government of National Defense". In 1917, when Greece joined the First World War, he was appointed nominal commander - in - chief of the Greek Army, a position he retained until the war's end, when he returned to his parliamentary office. In 1921, Danglis succeeded the self exiled Venizelos as president of the Liberal Party.

He died in Athens on March 9, 1924.

Pavlos Kountouriotis (Greek: Παύλος Κουντουριώτης, 9 April 1855 - 22 August 1935) was a Greek admiral and naval hero during the Balkan Wars and the first and third President of the Second Hellenic Republic.

The Kountouriotes was a prominent Arvanite family from the island of Hydra. The original family name was Zervas but was allegedly changed to Kountouriotis, since one of their ancestors lived for a while in the village of Kountoura, Megarida. Many members of the family took part in the Greek War of Independence, including his grandfather, Georgios Kountouriotis, who also served as Prime Minister of Greece under King Otto.

Pavlos Kountouriotis was born in the island if Hydra in April 1855 to Theodoros Kountouriotis, son of Georgios, and Loukia Negreponte. He was the second child of nine, including Ioannis Kountouriotis. Little is known of his childhood. In 1875, following his family's long naval tradition, he joined the Royal Hellenic Navy presumably at the rank of Ensign.

In 1886 he took part in the naval operations at Preveza as a Lieutenant. During the Greco - Turkish War of 1897, serving as Lt. Commander he commanded the ship Alfeios. His ship took part in at least two landings of Greek troops on the island of Crete. In 1901, commanding the training ship Miaoulis, he was sent to Boston. This was reported as the first transatlantic trip of a Greek war vessel. Kountouriotis served as an aide - de - camp to King George I from 1908 until 1911, receiving the rank of Captain in 1909. In June 1911, Kountouriotis was send to Britain, to take control of the newly commissioned Averof, following the "blue cheese mutiny". As he was highly esteemed, he quickly reimposed discipline and set sail for Greece.

He was promoted to Rear Admiral in 1912, on the outbreak of the First Balkan War. During the Balkan Wars, with his flagship, the Georgios Averof, he led the Greek Navy to major victories against the Turkish fleet in December 1912 (Battle of Elli) and in January 1913 (Battle of Limnos), liberating most of the Aegean islands. His victories, due in large part to his daring but successful tactics, earned him the status of a national hero. He was promoted to Vice Admiral for "exceptional war service", the first Greek career officer since Constantine Kanaris to reach the rank (usually reserved for members of the Greek royal family).

In 1916, he became a minister in the Stephanos Skouloudis government, but, in disagreement with the pro - German feelings of King Constantine I of Greece, he followed Eleftherios Venizelos to Thessaloniki where he was assigned the ministry of Naval Affairs in Venizelos' National Defense government. Constantine was deposed, and replaced on the throne by his son Alexander. Kountouriotis subsequently retired from the navy with the honorary rank of full Admiral. On the death of King Alexander of Greece in 1920, he was elected Regent of Greece by the Greek Parliament on 28 October by a vote of 137 to 3. After the sitting government of Venizelos was defeated in the elections that took place in November 1920, Kountouriotis resigned as Regent on 17 November, to be replaced by Queen Olga, Alexander's grandmother. The following month, King Constantine was restored.

In March 1924, after King George II of Greece was deposed, he was elected as the first President of the Second Hellenic Republic, but resigned the post in March, 1926 in opposition to General Pangalos' dictatorship. He was reelected president in May 1929, but due to serious health complications he resigned in December of the same year.

Pavlos Kountouriotis died in 1935. Α World War II Greek destroyer and a Standard class frigate, the F 462 Kountouriotis, are named after him.