<Back to Index>

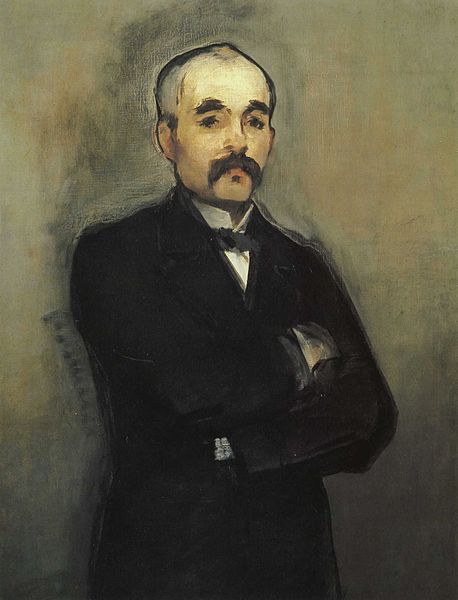

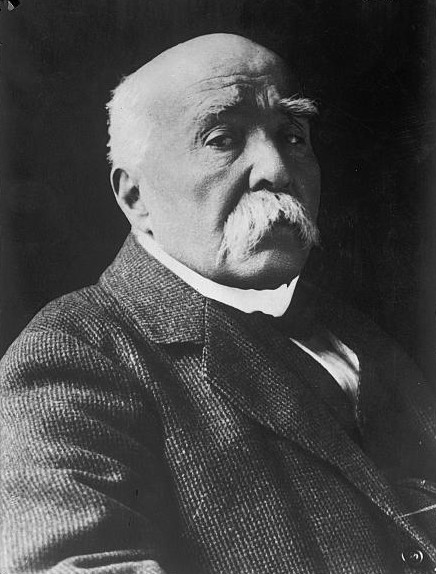

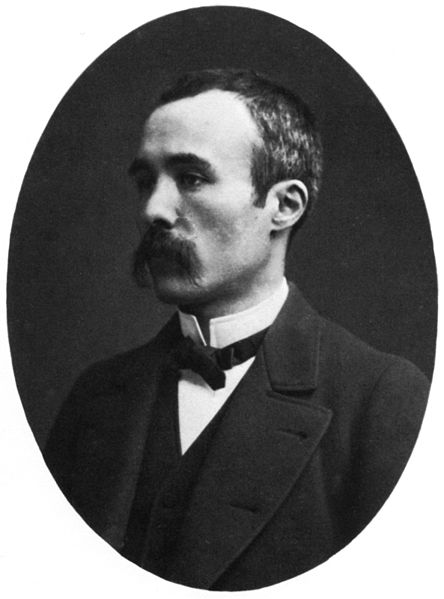

- Prime Minister of France Georges Benjamin Clemenceau, 1841

PAGE SPONSOR

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (28 September 1841 - 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who led the nation to victory in the First World War. A leader of the Radical Party, he played a central role in politics after 1870. Clemenceau served as the Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909, and again from 1917 to 1920. He was one of the principal architects of the Treaty of Versailles at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Nicknamed "Le Tigre" (The Tiger), he took a very harsh position against defeated Germany and won agreement on Germany's payment of large sums for reparations.

Clemenceau was a son of the Vendée, born at Mouilleron - en - Pareds. In Revolutionary times, the Vendée had been a hotbed of monarchist sympathies. By his birth, its people were fiercely republican. The region was remote from Paris, rural and poor. His mother Sophie Eucharie Gautreau (1817 - 1903) was of Huguenot descent. His father Benjamin Clemenceau (1810 - 1897) came from a long line of physicians, but he lived off his lands and investments and did not practice medicine. The father had a reputation as an atheist and a political activist; he was arrested and briefly held in 1851 and again in 1858. He instilled in his son a love of learning, devotion to the Revolution, and a hatred of Catholicism.

After his studies in the Nantes Lycée, Georges received his baccalaureate of letters in 1858. He went to Paris to study medicine but did not practice there.

In Paris, the young Clemenceau became a political activist and writer. In December 1861, he co-founded a weekly newsletter, Le Travail, along with some friends. On 23 February 1862, he was arrested by the police for having placed posters summoning a demonstration. He spent 77 days in the Mazas Prison.

He graduated as a doctor on 13 May 1865, founded several literary magazines, and wrote many articles, most of which attacked the imperial regime of Napoleon III. Clemenceau left France for the United States when the Imperial agents began cracking down on dissidents (sending most of them to the bagne de Cayennes (Devil's Island Penal System) in French Guiana).

Clemenceau worked in New York City 1865 - 69, following the American Civil War. He maintained a medical office but spent much of his time on political journalism for a Parisian newspaper. He took a post teaching French and horseback riding at a private girls' school in Stamford, Connecticut.

On 23 June 1869, he married one of his students, Mary Elizabeth Plummer (1850 - 1923), in New York City. She was the daughter of William Kelly Plummer and wife Harriet A. Taylor. The Clemenceaus had three children together before the marriage ended in divorce.

During this time he joined French exile clubs in New York opposing the imperial regime.

He returned to Paris after the fall of the regime with the defeat at Sedan. He took part in the Paris Commune but was there to establish the Third Republic. His political career began in earnest at this time.

He was elected to the Paris municipal council on 23 July 1871 for the Clignancourt quarter, and retained his seat till 1876, passing through the offices of secretary and vice-president, and becoming president in 1875.

In 1876 Clemenceau stood again for the Chamber of Deputies, and was elected for the 18th arrondissement. He joined the far left, and his energy and mordant eloquence speedily made him the leader of the Radical section. In 1877, after the Seize Mai crisis, he was one of the republican majority who denounced the de Broglie ministry. He led resistance to the anti - republican policy of which the Seize Mai incident was a manifestation. In 1879 his demand for the indictment of the de Broglie ministry brought him prominence.

In 1880 Clemenceau started his newspaper, La Justice, which became the principal organ of Parisian Radicalism. From this time, throughout Jules Grévy's presidency, he became widely known as a political critic and destroyer of ministries (le Tombeur de ministères) who avoided taking office himself. Leading the Far Left in the National Assembly, he was an active opponent of Jules Ferry's colonial policy (which he opposed on moral grounds and also as a form of diversion from the “Revenge against Germany”) and of the Opportunist party. In 1885 his criticism of the Tonkin disaster contributed strongly to the fall of the Ferry cabinet.

At the elections of 1885 he advocated a strong Radical program, and was returned both for his old seat in Paris and for the Var, district of Draguignan, selecting the latter. Refusing to form a ministry to replace the one he had overthrown, he supported the Right in keeping Freycinet in power in 1886, and was responsible for the inclusion of General Boulanger in the Freycinet cabinet as War Minister. When Boulanger showed himself as an ambitious pretender, Clemenceau withdrew his support and became a vigorous opponent of the heterogeneous Boulangist movement, though the Radical press and a section of the party continued to patronize the general.

By his exposure of the Wilson scandal, and by his personal plain speaking, Clemenceau contributed largely to Jules Grévy's resignation of the presidency in 1887. He had declined Grévy's request to form a cabinet on the downfall of Maurice Rouvier's Cabinet. by advising his followers to vote for neither Floquet, Ferry, or Freycinet, he was primarily responsible for the election of an "outsider", Sadi Carnot, as president.

The split in the Radical party over Boulangism weakened his hand, and its collapse meant that moderate Republicans did not need his help. A further misfortune occurred in the Panama affair, as Clemenceau's relations with Cornelius Herz led to his being included in the general suspicion. He remained the leading spokesman of French Radicalism, but his hostility to the Russian alliance so increased his unpopularity that in the 1893 election, he was defeated for his Chamber seat, after having held it continuously since 1876.

After his 1893 defeat, Clemenceau confined his political activities to journalism. His career was further overclouded by the long - drawn - out Dreyfus case, in which he took an active part as a supporter of Emile Zola and an opponent of the anti-Semitic and Nationalist campaigns. In all, Clemenceau published 665 articles defending Dreyfus during the affair.

On 13 January 1898 Clemenceau, as owner and editor of the Paris daily newspaper L'Aurore, published Émile Zola's "J'accuse" on the front page. He decided to run the controversial article, which would become a famous part of the Dreyfus Affair, in the form of an open letter to the President, Félix Faure.

In 1900 he withdrew from La Justice to found a weekly review, Le Bloc, to which he was practically the sole contributor. Le Bloc lasted until 15 March 1902. On 6 April 1902 he was elected senator for the Var, district of Draguignan, although he had previously called for the suppression of the Senate, as he considered it a strong-house of conservatism. He served as senator of Draguignan until 1920.

He sat with the Radical Socialist Party and moderated his positions, although he still vigorously supported the Combes ministry, who spearheaded the anti - clericalist Republican struggle. In June 1903 he undertook the direction of the journal L'Aurore, which he had founded. In it he led the campaign to revisit the Dreyfus affair, and to create a separation of Church and State. The latter was implemented by the 1905 Act.

In March 1906 the Rouvier ministry fell, owing to the riots provoked by the inventories of church property, and the Radicals' victory during the 1906 legislative election. The new government Ferdinand Sarrien appointed Clemenceau as Minister of the Interior in the cabinet. On a domestic level, Clemenceau reformed the police forces and ordered repressive policies towards the workers' movement. He supported the formation of scientific police by Alphonse Bertillon, and founded the Brigades mobiles (French for "mobile squads") led by Célestin Hennion. These squads were nicknamed Brigades du Tigre ("Tiger's Brigades") after Clemenceau himself.

The miners' strike in the Pas de Calais after the disaster at Courrieres, which resulted in more than one thousand dead, threatened wide disorder on 1 May 1906. Clemenceau used the military against the strikers and repressed the wine growers' strike in the Languedoc - Roussillon. His actions alienated the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) socialist party, from which he definitively broke in his notable reply in the Chamber to Jean Jaurès, leader of the SFIO, in June 1906.

His speech positioned him as the strong man of the day in French politics; when the Sarrien ministry resigned in October, Clemenceau became premier. During 1907 and 1908, he led the development of a new Entente cordiale with England, France had a successful role in European politics. Difficulties with Germany and criticism by the Socialist party in connection with Morocco (First Moroccan Crisis in 1905 - 06, were settled by the Algeciras Conference).

Clemenceau was defeated on 20 July 1909 in a discussion in the Chamber on the state of the Navy, in which bitter words were exchanged between him and Théophile Delcassé, the former president of the Council whose downfall Clemenceau had aided. Refusing to respond to Delcassé's technical questions, Clemenceau resigned after his proposal for the order of the day vote was rejected. He was succeeded as premier by Aristide Briand, with a reconstructed cabinet.

Between 1909 and 1912, Clemenceau dedicated his time to travels, conferences and also to the treatment of his sickness. He went to South America in 1910, traveling to Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina (where he went as far as Santa Ana de Tucuman in the North West of Argentina). There, he was amazed by the influence of French culture and of the French Revolution on local elites. In 1912, he was operated on because of a problem of the prostate.

He published the first issue of the Journal du Var on 10 April 1910. Three years later on 6 May 1913, he founded L'Homme libre (The Free Man) newspaper in Paris, for which he wrote a daily editorial. In these media, Clemenceau focused increasingly on foreign policy, and condemned the Socialists' anti - militarism.

When the First World War broke out, his newspaper was one of the first to be censored by the government; it was suspended from 29 September 1914 to 7 October. In response, Clemenceau changed its name to L'Homme enchaîné (The Man in Chains). He criticized the government for the lack of transparency of the government and its ineffectiveness, while defending the patriotic Union sacrée against the German Empire.

When the First World War broke out in 1914 Clemenceau refused to act as justice minister. He was a vehement critic of the government, complaining that it was never doing enough to win the war. He rejected any talk of a compromise peace. The prominence of his opposition made him the best known critic and the last man standing when the others had failed.

When the hour was darkest in November 1917 Clemenceau was appointed prime minister. Unlike his predecessors, he discouraged internal disagreement and called for peace among the senior politicians.

Churchill later wrote that Clemenceau "looked like a wild animal pacing to and fro behind bars" in front of "an assembly which would have done anything to avoid putting him there, but, having put him there, felt they must obey".

When Clemenceau became Prime Minister in 1917 victory seemed to be a long way off. There was little activity on the Front because it was believed that there should be limited attacks until the American support arrived. At this time, Italy was on the defensive, Russia had virtually stopped fighting – and it was believed they would be making a separate peace with Germany. At home the government had to combat increasing resentment against the war. They also had to handle increasing demonstrations against the war, scarcity of resources and air raids – which were causing huge physical damage to Paris as well as damaging the morale of its citizens. It was also believed that many politicians secretly wanted peace. It was a challenging situation for Clemenceau, because after years of criticizing other men during the war, he suddenly found himself in a position of supreme power. He was also isolated politically. He did not have close links with any parliamentary leaders (especially after years of criticism) and so had to rely on himself and his own circle of friends.

Clemenceau's ascension to power meant little to the men in the trenches at first. They thought of him as "Just another Politician", and the monthly assessment of troop morale found that only a minority found comfort in his appointment. Slowly, however, as time passed, the confidence he inspired in a few began to grow throughout all the fighting men. They were encouraged by his many visits to the trenches. This confidence began to spread from the trenches to the home front and it was said "We believed in Clemenceau rather in the way that our ancestors believed in Joan of Arc." After years of criticism against the French army for its conservatism and Catholicism, Clemenceau would need help to get along the military leaders in order to achieve a sound strategic plan. He nominated general Henri Mordacq to be his military chief of staff. Mordacq helped inspiring trust and mutual respect from the army to the government which proved essential to the final victory.

Clemenceau was also well received by the media because they felt that France was in need for strong leadership. It was widely recognized that throughout the war he was never discouraged and he never stopped believing that France could achieve total victory. There were skeptics, however, that believed that Clemenceau, like other war time leaders, would have a short time in office. It was said that "Like everyone else … Clemenceau will not last long- only long enough to clean up [the war]."

As the situation worsened in early 1918, Clemenceau continued to support the policy of total war – "We present ourselves before you with the single thought of total war" – and the policy of "la guerre jusqu'au bout" (war until the end). His 8 March speech advocating this policy was so effective it left a vivid impression on Winston Churchill, who would make similar speeches on becoming British Prime Minister in 1940. Clemenceau's war policy encompassed the promise of victory with justice, loyalty to the fighting men, and immediate and severe punishment of crimes against France.

Joseph Caillaux, a former French prime minister, disagreed with Clemenceau's policies. He was a believer in negotiating peace by surrendering to Germany. Clemenceau observed Caillaux as a threat to national security. Unlike previous ministers, Clemenceau publicly stepped against Caillaux. As a result, the parliamentary committee decided that Caillaux would be arrested and imprisoned for three years. Clemenceau believed, in the words of Jean Ybarnégaray, that Caillaux's crime "was not to have believed in victory [and] to have gambled on his nation's defeat".

It was believed by some in Paris that the arrest of Caillaux and others was a sign that Clemenceau had begun a Reign of Terror. The many trials and arrests aroused great public excitement, one newspaper ironically reported "The war must be over, for no one is talking about it anymore". These trials, far from making the public fear the government, inspired confidence as they felt that for the first time in the war, action was being taken and they were being firmly governed. The claims that Clemenceau's "firm government" was a dictatorship found little support. Clemenceau was still held accountable to the people and media. He relaxed censorship on political views as he believed that newspapers had the right to criticize political figures – "The right to insult members of the government is inviolable". The only powers that Clemenceau assumed were those that he thought necessary to win the war.

In 1918, Clemenceau thought that France should adopt Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, mainly because of its point that called for the return of the disputed territory of Alsace - Lorraine to France. This meant that victory would fulfill the war aim that was crucial for the French public. Clemenceau was however skeptical about some other points, including those concerning the League of Nations, as he believed that the latter could succeed only in a utopian society.

As war minister Clemenceau was also in close contact with his generals. However, he did not always make the most effective decisions concerning military issues (though he did heed the advice of the more experienced generals). As well as talking strategy with the generals he also went to the trenches to see the Poilu, the French infantrymen. He would speak to them and assure them that their government was actually looking after them. The Poilu had great respect for Clemenceau and his disregard for danger as he often visited soldiers only yards away from German front lines. These visits contributed to Clemenceau's title Le Père de la Victoire (Father of Victory).

On 21 March the Germans began their great Spring Offensive. The Allies were caught off guard as they were waiting for the majority of the American troops to arrive. As the Germans advanced on 24 March, the British Fifth army retreated and a gap was created in the British/French lines – giving them access to Paris. This defeat cemented Clemenceau's belief, and that of the other allies, that a coordinated, unified command was the best option. It was decided that Foch would be appointed to the supreme command.

The German line continued to advance and Clemenceau believed that they could not rule out the fall of Paris. It was believed that if "the tiger" as well as Foch and Pétain stayed in power, for even another week, France would be lost. It was thought that a government headed by Briand would be beneficial to France because he would make peace with Germany on advantageous terms. Clemenceau adamantly opposed these opinions and he gave an inspirational speech to parliament and "the chamber" voted their confidence in him 377 votes to 110.

As the Allied counter-offensives began to push the Germans back, with the help of American reinforcements, it became clear that the Germans could no longer win the war. Although they still occupied allied territory, they did not have sufficient resources and manpower to continue the attack. As countries allied to Germany began to ask for an armistice, it was obvious that Germany would soon follow. On 11 November an armistice with Germany was signed – Clemenceau saw this was Germany's admission of defeat. Clemenceau was embraced in the streets and attracted admiring crowds. He was a strong, energetic, positive leader who was key to the allied victory of 1918.

It was decided that a peace conference would be held in Paris, France. (The treaty signed by both parties was signed in the Palace of Versailles, but deliberated upon in Paris). On 13 December Woodrow Wilson received an enormous welcome. His Fourteen Points and the concept of a League of Nations had made a big impact on the war weary French. Clemenceau realized at their first meeting that he was a man of principle and conscience but narrow minded.

It was decided that since the conference was being held in France, Clemenceau would be the most appropriate president. He also spoke both English and French, the official languages of the conference.

The Conference progress was much slower than anticipated and decisions were constantly being tabled. It was this slow pace that induced Clemenceau to give an interview showing his irritation to an American journalist. He said he believed that Germany had won the war industrially and commercially as its factories were intact and its debts would soon be overcome through ‘manipulation’. In a short time, he believed, the German economy would be much stronger than the French.

France's diplomatic position at the Paris Peace Conference was repeatedly jeopardized by Clemenceau's mistrust of David Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson, and his intense dislike of French President Raymond Poincaré. When negotiations reached a stalemate, Clemenceau had a habit of shouting at the other heads of state and storming out of the room rather than participating in further discussion.

On 19 February 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference, as Clemenceau was leaving his house in the Rue Franklin to drive to a meeting with House and Balfour at the Crillon, a man jumped out and fired several shots at the car. One bullet hit Clemenceau between the ribs, just missing his vital organs. Too dangerous to remove, the bullet remained with him for the remainder of his life. Clemenceau's assailant, Emile Cottin, was seized by the crowd following the leader's procession and nearly lynched. Taken back to his house, Clemenceau's faithful assistant found him pale but conscious. "They shot me in the back," Clemenceau told him. "They didn't even dare to attack me from the front."

Clemenceau often joked about the "assassin's" bad marksmanship – “We have just won the most terrible war in history, yet here is a Frenchman who misses his target 6 out of 7 times at point blank range. Of course this fellow must be punished for the careless use of a dangerous weapon and for poor marksmanship. I suggest that he be locked up for eight years, with intensive training in a shooting gallery."

When Clemenceau returned to the council of ten on 1 March he found that little had changed. One issue that had not changed was a dispute over the long running Eastern Frontier and control of the German province Rhineland. Clemenceau believed that Germany's possession of the territory left France without a natural frontier in the East and so simplified invasion into France for an attacking army. The British ambassador reported in December 1918 on Clemenceau's views on the future of the Rhineland: "He said that the Rhine was a natural boundary of Gaul and Germany and that it ought to be made the German boundary now, the territory between the Rhine and the French frontier being made into an Independent State whose neutrality should be guaranteed by the great powers".

The issue was finally resolved when Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson guaranteed immediate military assistance if Germany attacked without provocation. It was also decided that the Allies would occupy the territory for fifteen years, and that Germany could never rearm the area. Lloyd George insisted on a clause allowing for the early withdrawal of Allied troops if the Germans fulfilled the treaty; Clemenceau inserted Article 429 into the treaty that permitted the Allied occupation beyond the fifteen years if adequate guarantees for Allied security against unprovoked aggression were not met. This was in case the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the treaty of guarantee, thereby making null and void the British guarantee as well as that was dependent on the Americans being part of it. This is, in fact, what did occur. Article 429 ensured that a refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify the treaties of guarantee would not weaken them.

President Poincaré and Marshal Foch both repeatedly pressed for an autonomous Rhineland state. At a Cabinet meeting on 25 April Foch spoke against the deal Clemenceau had brokered and pushed for a separate Rhineland. On 28 April Poincaré sent Clemenceau a long letter detailing why he thought Allied occupation should continue until Germany had paid all her reparations. Clemenceau replied that the alliance with America and Britain was of more value than an isolated France which held onto the Rhineland: "In fifteen years I will be dead, but if you do me the honor of visiting my tomb, you will be able to say that the Germans have not fulfilled all the clauses of the treaty, and that we are still on the Rhine". Clemenceau said to Lloyd George in June: "We need a barrier behind which, in the years to come, our people can work in security to rebuild its ruins. The barrier is the Rhine. I must take national feelings into account. That does not mean that I am afraid of losing office. I am quite indifferent on that point. But I will not, by giving up the occupation, do something which will break the willpower of our people". He said later to Jean Martet: "The policy of Foch and Poincaré was bad in principle. It was a policy no Frenchman, no republican Frenchman could accept for a moment, except in the hope of obtaining other guarantees, other advantages. We leave that sort of thing to Bismarck".

There was increasing discontent among Clemenceau, Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson about slow progress and information leaks surrounding the Council of Ten. They began to meet in a smaller group, called the Council of Four, Vittorio Orlando of Italy being the fourth, though less weighty, member. This offered greater privacy and security and increased the efficiency of the decision making process. Another major issue which the Council of Four discussed was the future of the German Saar province. Clemenceau believed that France was entitled to the province and its coal mines after Germany deliberately damaged the coal mines in Northern France. Wilson, however, resisted the French claim so firmly that Clemenceau accused him of being ‘pro German’. Lloyd George came to a compromise and the coal mines were given to France and the territory placed under French administration for 15 years, after which a vote would determine whether the province would rejoin Germany.

Although Clemenceau had little knowledge of the Austrian - Hungarian empire, he supported the causes of its smaller ethnic groups and his adamant lead to the stringent terms in the Treaty of Trianon which dismantled Hungary. Rather than recognizing territories of the Austrian-Hungarian empire solely within the principles of self determination, Clemenceau sought to weaken Hungary just as Germany and remove the threat of such a large power within Central Europe. The entire Czechoslovakian state was seen a potential buffer from Communism and this encompassed majority Hungarian territories.

Clemenceau was not experienced in the fields of economics or finance, but was under strong public and parliamentary pressure to make Germany’s reparation bill as large as possible. It was generally agreed that Germany should not pay more than it could afford, but the estimates of what it could afford varied greatly. Figures ranged between £2,000 million which was quite modest compared to another estimate of £20,000 million. Clemenceau realized that any compromise would anger both the French and British citizens and that the only option was to establish a reparations commission which would examine Germany’s capacity for reparations. This meant that the French government was not directly involved in the issue of reparations.

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. Clemenceau now had to defend the treaty against critics who viewed the compromises Clemenceau had negotiated as inadequate for French national interests. The French Parliament debated the treaty and Louis Barthou on 24 September claimed that the U.S. Senate would not vote for the treaty of guarantee or of Versailles and therefore it would have been wiser to have the Rhine as a frontier. Clemenceau replied that he was sure the Senate would ratify both and that he had inserted Article 429 into the treaty, providing for "new arrangements concerning the Rhine". This interpretation of Article 429 was disputed by Barthou.

Clemenceau's main speech on the treaty was delivered on 25 September. He said that he knew the treaty was not perfect but that the war had been fought by a coalition and therefore the treaty would express the lowest common denominator of those involved. He claimed criticisms of the details of the treaty were misleading; they should look as the treaty as a whole and see how they could benefit from it:

The treaty, with all its complex clauses, will only be worth what you are worth; it will be what you make it...What you are going to vote to-day is not even a beginning, it is a beginning of a beginning. The ideas it contains will grow and bear fruit. You have won the power to impose them on a defeated Germany. We are told that she will revive. All the more reason not to show her that we fear her...M. Marin went to the heart of the question, when he turned to us and said in despairing tones, ‘You have reduced us to a policy of vigilance.’ Yes, M. Marin, do you think that one could make a treaty which would do away with the need for vigilance among the nations of Europe who only yesterday were pouring out their blood in battle? Life is a perpetual struggle in war, as in peace...That struggle cannot be avoided. Yes, we must have vigilance, we must have a great deal of vigilance. I cannot say for how many years, perhaps I should say for how many centuries, the crisis which has begun will continue. Yes, this treaty will bring us burdens, troubles, miseries, difficulties, and that will continue for long years.

The Chamber of Deputies ratified the treaty by 372 votes to 53, with the Senate voting unanimously for its ratification. On 11 October he gave his last parliamentary speech, to the Senate. He said that any attempt to partition Germany would be self-defeating and that France must find a way of living with sixty million Germans. He also said that the bourgeoisie, like the aristocracy before them in the ancien régime, had failed as a ruling class. It was now the turn of the working class to rule. He advocated national unity and a demographic revolution: "The treaty does not state that France will have many children, but it is the first thing that should have been written there. For if France does not have large families, it will be in vain that you put all the finest clauses in the treaty, that you take away all the Germans guns, France will be lost because there will be no more French".

In 1919 France adopted a new electoral system and the legislative election gave the National Bloc (a coalition of right wing parties) a majority. Clemenceau only intervened once in the election campaign, delivering a speech on 4 November at Strasbourg, praising the manifesto and men of the National Bloc and urging that the victory in the war needed to be safeguarded by vigilance. In private he was concerned at this huge swing to the right.

His friend Georges Mandel urged Clemenceau to stand for the Presidency in the upcoming election and on 15 January 1920 he let Mandel announce that he would be prepared to serve if elected. However Clemenceau did not intend to campaign for the post, instead he wished to be chosen by acclaim as a national symbol. The preliminary meeting of the republican caucus (a forerunner to the vote in the National Assembly) chose not Clemenceau but Paul Deschanel by 408 votes to 389. In response Clemenceau refused to be put forward for the vote in the National Assembly because he did not want to win by a small majority but by a near-unanimous vote. Only then, he claimed, could he negotiate with confidence with the Allies.

In his last speech to the Cabinet on 18 January he said: "We must show the world the extent of our victory, and we must take up the mentality and habits of a victorious people, which once more takes its place at the head of Europe. But all that will now be placed in jeopardy... It will take less time and less thought to destroy the edifice so patiently and painfully erected than it took to complete it. Poor France. The mistakes have begun already".

Clemenceau resigned as Prime Minister as soon as the Presidential election was held and took no further part in politics. In private he condemned the unilateral occupation by French troops of the German city of Frankfurt in 1920 and said if he had been in power he would have persuaded the British to join it.

He took a holiday in Egypt and the Sudan from February to April 1920, then embarking for the Far East in September, returning to France in March 1921. In June he visited England and received an honorary degree from Oxford. He met Lloyd George and said to him that after the Armistice he had become the enemy of France. Lloyd George replied: “Well, was not that always our traditional policy?” He was joking but after reflection Clemenceau took it seriously. After Lloyd George's fall from power in 1922 Clemenceau remarked: “As for France, it is a real enemy who disappears. Lloyd George did not hide it: at my last visit to London he cynically admitted it”.

In late 1922 Clemenceau gave a lecture tour in the major cities of the American north east. He defended the policy of France, including war debts and reparations, and condemned American isolationism. He was well received and attracted large audiences but America's policy remained unchanged. On 9 August 1926 he wrote an open letter to the American President Calvin Coolidge, arguing against France paying all its war debts: "France is not for sale, even to her friends". This appeal went unheard.

He condemned Poincaré's occupation of the Ruhr as undoing of the entente between France and Britain.

He wrote two short biographies of the Greek orator Demosthenes and the French painter Claude Monet. He also penned a huge two volume tome, covering philosophy, history and science, titled Au Soir de la Pensée. Writing this occupied most of his time between 1923 and 1927.

During his last months he wrote his memoirs, despite declaring previously that he would not write them. He was spurred into doing so by the appearance of Marshal Foch's memoirs which were highly critical of Clemenceau, mainly for his policy at the Paris Peace Conference. He only had time to finish the first draft and it was published posthumously as Grandeurs et Misères d'une Victoire (The Grandeur and Misery of Victory). He was critical of Foch and also of his successors who had allowed the Versailles treaty to be undermined in the face of Germany's revival. He burned all his private letters.

Clemenceau was a long-time friend and supporter of the impressionist painter Claude Monet. He was instrumental in convincing Monet to have a cataract operation in 1923, and for over a decade encouraged Monet to complete his donation to the French state of the "Nymphéas" (Water Lilies) paintings that are now on display in Paris' Musée de l'Orangerie in specially constructed oval galleries (which opened to the public in 1927).