<Back to Index>

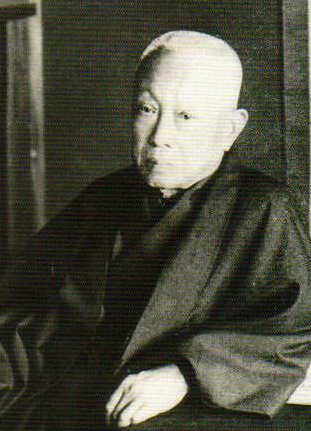

- Prime Minister of Japan Saionji Kinmochi, 1849

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Makino Nobuaki, 1861

PAGE SPONSOR

Prince Saionji Kinmochi (西園寺 公望, 23 October 1849 - 24 November 1940) was a Japanese politician, statesman and twice Prime Minister of Japan. His title does not signify the son of an emperor, but the highest rank of Japanese hereditary nobility; he was elevated from marquis to prince in 1920. As the last surviving genrō, he was Japan's most honored statesman of the 1920s and 1930s.

Kinmochi was born in Kyoto as the son of Udaijin Tokudaiji Kin'ito (1821 - 1883), head of a kuge family of court nobility. He was adopted by another kuge family, the Saionji, in 1851. However, he grew up near his biological parents, since both the Tokudaiji and Saionji lived very near the Kyoto Imperial Palace. The young Saionji Kinmochi was frequently ordered to visit the palace as a playmate of the young prince who later became Emperor Meiji. Over time they became close friends. Kinmochi's biological brother Tokudaiji Sanetsune later became the Grand Chamberlain of Japan. Another younger brother was adopted into the very wealthy Sumitomo family and as Sumitomo Kichizaemon became the head of the Sumitomo zaibatsu. Sumitomo money largely financed Saionji's political career. His close relationship to the Imperial Court opened all doors to him. In his later political life, he was an influence on both the Taishō and Shōwa emperors.

As the heir of a noble family, Saionji participated in politics from an early age and was known for his brilliant talent. He took part in the climactic event of his time, the Boshin War, the revolution in Japan of 1867 and 1868, which overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate and installed the young Emperor Meiji as the (nominal) head of the government. Some noblemen at the Imperial Court considered the war to be a private dispute of the samurai of Satsuma and Choshu against those of the Tokugawa. Saionji held the strong opinion that the nobles of the Imperial Court should seize the initiative and take part in the war. He participated in various battles as an imperial representative.

One of his first encounters involved taking Kameoka Castle without a fight. The next encounter was at Sasayama Castle. Several hundred Samurai from both sides met on the road nearby, but the defenders immediately surrendered. Then Fukuchiyama surrendered without a fight. By this time he had acquired an Imperial banner made by Iwakura Tomomi, featuring a sun and moon on a red field. Other Samurai did not want to attack the army with the imperial banner, and readily deserted the Shogun. After two weeks Saionji reached Kizuki, and following another bloodless encounter, Saionji returned by ship to Osaka. Matters did eventually come to an end at Nagaoka Castle. However, Saionji was relieved from command in the actual battle and appointed governor of Echigo.

After the Meiji Restoration, Saionji resigned. With the support of Ōmura Masujirō he studied French in Tokyo. He left Japan on SS Costa Rica with a group of thirty other Japanese students sailing to San Francisco. He traveled on to Washington where he met Ulysses Grant, President of the United States of America. He then crossed the Atlantic spending 13 days in London sightseeing, before finally arriving in Paris on 27 May 1871. Paris was in the turmoil of the Commune, and Paris was not safe for Saionji - indeed his tutor was shot when they stumbled upon a street battle. Saionji went to Switzerland and Nice, before settling in Marseilles where he learned French with the accent of that city. He made his way to Paris following the suppression of the Commune. He studied law at the Sorbonne and became involved with Emile Acollas, who had set up the Acollas Law School for foreign students studying law in Paris. These were the early years of the Third Republic, a time of high idealism in France. Saionji arrived in France with highly reactionary views but he was influenced by Acollas (a former member of the League of Peace and Freedom) and became the most liberal of Japanese major political figures of his generation. When the Iwakura Mission visited Paris in 1872, Iwakura was quite worried about the radicalism of Saionji and other Japanese students. He made many acquaintances in France, including Franz Liszt, the Goncourt brothers and fellow Sorbonne student Georges Clemenceau.

On his return to Japan, he founded the Ritsumeikan University in 1869 and Meiji Law School, which later evolved into Meiji University in 1880.

In 1882, Itō Hirobumi visited Europe in order to research the constitutional systems of each major European country, and he asked Saionji to accompany him, as they knew each other very well. After the trip, he was appointed ambassador to Austria - Hungary, and later to Germany and Belgium.

Returning to Japan, Saionji joined the Privy Council, and served as president of the House of Peers. He also served as Minister of Education in the 2nd and 3rd Itō administrations (1892 - 1893, 1898) and 2nd Matsukata administration. During his tenure, he strove to improve the quality of the educational curriculum towards an international (i.e., western) standard.

In 1900, Itō founded the Rikken Seiyūkai political party, and Saionji joined as one of the first members. Due to his experiences in Europe, Saionji had a liberal political point of view and supported parliamentary government. He was one of the few early politicians who claimed that the majority party in parliament had to be the basis for forming a cabinet.

Saionji replaced Itō as president of the Privy Council in 1900, and as president of the Rikken Seiyūkai in 1903.

From 7 January 1906 to 14 July 1908, and again from 30 August 1911 to 21 December 1912, Saionji served as Prime Minister of Japan.

Both his ministries were marked by continuing tension between Saionji and the powerful arch conservative genrō, Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo. Saionji and Itō saw political parties as a useful part of the machinery of government; Yamagata looked on political parties and all democratic institutions as quarrelsome, corrupt and irrational.

Saionji had to struggle with the national budget with many demands and finite resources, Yamagata sought ceaselessly the greatest expansion of the army. Saionji's first cabinet was brought down in 1908 by conservatives led by Yamagata who were alarmed at the growth of socialism, who felt the government's suppression of socialists (after a parade and riots) had been insufficiently forceful.

The fall of Saionji's second cabinet was a major reverse to constitutional government. The Taishō Crisis (so named for the newly enthroned emperor) erupted in late November 1912, out of the continuing bitter dispute over the military budget. The army minister, General Uehara, unable to get the cabinet to agree on the army's demands, resigned. Saionji sought to replace Uehara.

A Japanese law (intended to give added power to the army and navy) required that the army minister must be a lieutenant general or general on active duty. All of the eligible generals, on Yamagata's instruction, refused to serve in Saionji's cabinet. The cabinet was then forced to resign. The precedent had been established that the army could force the resignation of a cabinet.

Saionji's political philosophy was heavily influenced by his background; he believed the Imperial Court should be guarded and that it should not participate directly in politics: the same strategy employed by noblemen and the Court in Kyoto for hundreds of years. This was another point in which he was opposed by nationalists in the Army, who wished for the Emperor to participate in Japanese politics directly and thus weaken both parliament and the cabinet. Nationalists also accused him of being a 'globalist'.

Saionji was appointed a genrō in 1913. The role of the genrō at this time was diminishing; their main function was to choose the prime ministers - formally, to nominate candidates for Prime Minister to the Emperor for approval, but no Emperor ever rejected their advice. From the death of Matsukata Masayoshi in 1924 Saionji was the sole surviving genrō. He exercised his prerogative of naming the prime ministers very nearly until his death in 1940 at the age of 91. Saionji, when he could, chose as prime minister the president of the majority party in the Diet, but his power was always constrained by the necessity of at least the tacit consent of the army and navy. He could choose political leaders only when they might be strong enough to form an effective government. He nominated military men and non party politicians when he felt necessary.

In 1919 Saionji led the Japanese delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, though his role was largely symbolic due to ill health. Nevertheless, he courageously proposed that racial equality should have been legally enshrined as one of the basic tenets of the newly formed League of Nations, but both the USA and Great Britain opposed his proposal and prompted its rejection from the delegates, very likely because of the destabilizing effects it would have wreaked upon their respective racially segregated societies. Saionji, a never - married man of 70, was accompanied to Paris by his son, his favorite daughter and his current mistress. In 1920 he was given the title kōshaku (公爵, Prince) as an honor for a life in public service.

He was detested by the militarists and was on the list of those to be assassinated in the attempted coup of February 26, 1936. Saionji, on receiving news of the mutiny, fled from his home for his life in his car, pursued for a great distance by a strange car that he and his companions supposed held soldiers bent on his murder. It held newspaper reporters.

In much of his career, Saionji tried to diminish the influence of the Imperial Japanese Army in political issues. He was one of the most liberal of Emperor Hirohito's advisors, and favored friendly relations with Great Britain and the United States. However, he was careful to pick his battles, and often accepted defeat by the militarists when placed into a position from which he could not easily win, thus was unable to prevent the Tripartite Pact.

Count Makino Nobuaki (牧野 伸顕, November 24, 1861 - January 25, 1949) was a Japanese statesman, active from the Meiji period through the Pacific War.

Born to a samurai family in Kagoshima, Satsuma domain (present day Kagoshima Prefecture), Makino was the second son of Ōkubo Toshimichi, but adopted into the Makino family at a very early age.

In 1871, at the age of 11, he accompanied Ōkubo on the Iwakura Mission to the United States as a student, and briefly attended school in Philadelphia. After he returned to Japan, he attended Tokyo Imperial University, but left without graduating to enter the Foreign Ministry. Assigned to the Japanese London Embassy, he made the acquaintance of Itō Hirobumi.

After serving as governors of Fukui Prefecture (1891 - 1892), Ibaraki Prefecture (1892 - 1893), Ambassador to the Austria - Hungary Empire and Ambassador to Italy, he served as Minister of Education under the 1st Saionji Cabinet, and as Minister of Agriculture and Commerce under the 2nd Saionji Cabinet. He was also appointed to serve on the Privy Council. Under the 1st Yamagata Cabinet, he was appointed Foreign Minister. Makino aligned his policies closely with Itō Hirobumi and later, with Saionji Kinmochi, and was considered one of the early leaders of the Liberalism movement in Japan. He was appointed to be Japan's ambassador plenipotentiary to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, ending World War I. Makino and his delegation put forth a racial equality proposal at the conference which did not pass.

In 1907, Makino elevated in rank to danshaku (baron) under the kazoku peerage system. In 1913, Makino became Minister of Foreign Affairs. On September 20, 1920, he was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers. In February 1921, he became Imperial Household Minister and elevated in rank to shishaku (viscount). Behind the scenes, he strove to improve Anglo - Japanese and Japanese - American relations, and he shared Saionji Kinmochi's efforts to shield the Emperor from direct involvement in political affairs. In 1925, he was appointed Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan. He relinquished the post in 1935, and was elevated in title to hakushaku (count). Although he relinquished his positions, his relations with Emperor Shōwa remained good, and he still had much power and influence behind the scenes. This made him a target for the militarists, and he narrowly escaped assassination at his villa in Yugawara during the February 26 Incident in 1936. He continued to be an advisor and exert a moderating influence on the Emperor until the start of World War II.

Makino was also first president of the Nihon Ki-in Go Society, and a fervent player of the game of go.

After the war, his reputation as an "old liberalist" gave him high credibility, and the politician Hatoyama Ichirō attempted to recruit him to the Liberal Party as its chairman. However, Makino declined for reasons of health and age. He died in 1949, and his grave is at the Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo.

Noted post war Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru was Makino's son - in - law, and the former Prime Minister, Asō Tarō, was Makino's great - grandson. In addition, Ijuin Hikokichi, former foreign minister, was brother - in - law of Makino.