<Back to Index>

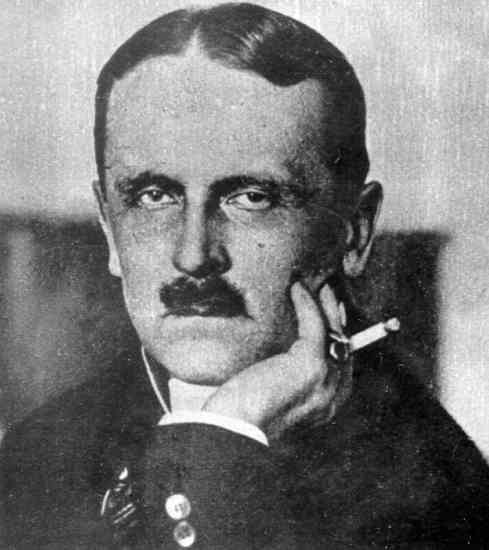

- Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff - Rantzau, 1869

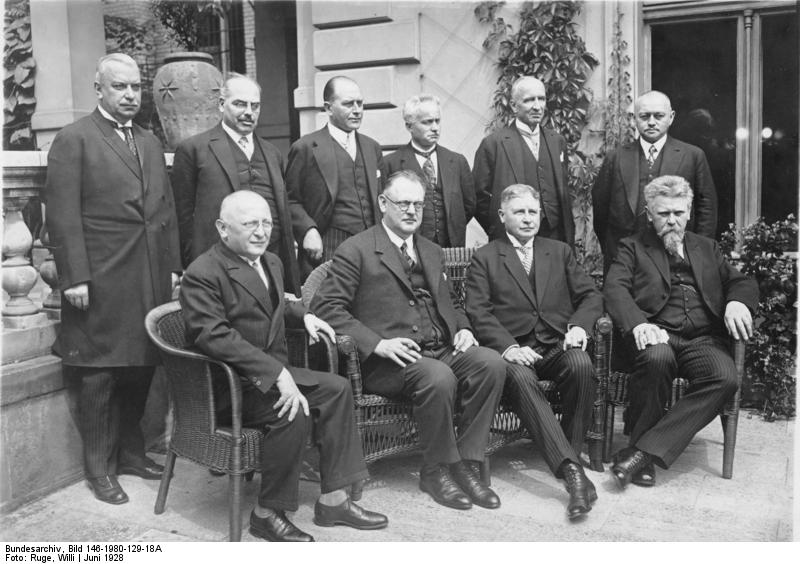

- 12th Chancellor of Gernany Hermann Müller, 1876

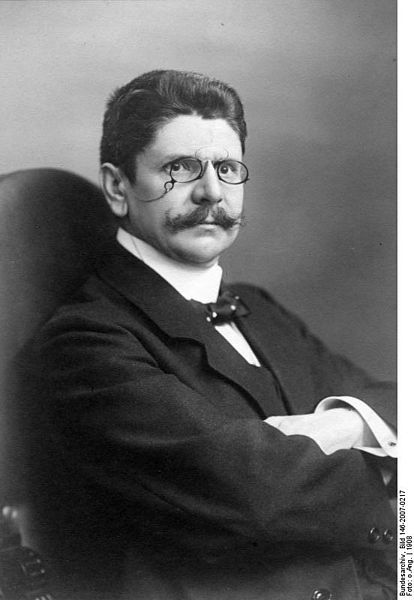

- Minister of Transport and Minister of Justice Johannes Bell, 1868

PAGE SPONSOR

Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau (May 29, 1869 Schleswig - September 8, 1928 Berlin) was a German diplomat, the first Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic and German Ambassador to the USSR for most of the twenties.

Son of Graf Hermann zu Rantzau and Juliane nee von Brockdorff, Brockdorff - Rantzau completed study of jurisprudence in Neuchâtel and Freiburg im Breisgau and became a Dr. jur in 1891. Between 1891 and 1893 he served with the Prussian army; he was dismissed as a second lieutenant after suffering an injury. He then entered the Foreign Office as a diplomat. From 1897 to 1901 he was secretary to the embassy in St Petersburg. In 1901 he moved on to Vienna. From 1909 to 1912 he was attached to the Consul General in Budapest. Finally, in 1912, he was made ambassador to Denmark. In this position he was able to ensure the exchange of German coal for Danish food supplies. He came in close contact with Danish and German trade unions and got to know the future German president Friedrich Ebert. He was also instrumental in facilitating the passage of the Bolsheviks Vladimir Lenin and Karl Radek across Germany in a sealed train in 1917.

He was offered the post of Außenstaatssekretär (State Secretary for Foreign Affairs) following Arthur Zimmermann's resignation in 1917, but declined because he did not believe he could follow a policy independent from military interference. This stance characterized his subsequent diplomatic career. However in December 1918, he accepted this post in the government of Philipp Scheidemann dependent on five conditions:

- A national Constituent assembly should be convened before February 16, 1919 to ensure the Council of People's Deputies could have a constitutional basis.

- Germany's credit rating should be restored to facilitate loans from the U.S.A.

- A republican Army should be immediately created to hold back the prospect of a communist revolution and to create a stronger negotiating position for Germany at the Peace Conference.

- All possible steps should be made remove the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils from involvement in the state.

- He demanded the right to participate in domestic problems and to reject a dictated peace if he felt it threatened Germany's future.

Ebert of the SPD and Hugo Haase of the USPD agreed to the first four conditions and he received the appointment arriving in Berlin January 2, 1919. On February 13 his title was changed to Reichsminister des Auswärtigen (Imperial Minister of Foreign Affairs) as part of the founding of the Weimar Republic.

Although he was to develop a policy of a positive relationship with the Soviet Union, this was based on realpolitik considerations rather than any sympathy for radicalism. Faced with the German Revolution, he advocated stern measures against the revolutionaries, threatening to resign if this was not done. The threat of resignation became a regular feature of his negotiating strategy. Nevertheless when Matthias Erzberger advocated the dispatch of Karl Radek, the captured Bolshevik diplomat, to the waiting hands of the Entente, he was furious about the failure to consider the political consequences.

After the defeat of the Spartacists in January 1919, the country wide elections for the constituent assembly continued, with the delegates assembling in Weimar as Berlin was not safe. On February 14 Brockdorff - Rantzau addressed the National Assembly. He stated that Germany was ready to make peace, but did not accept that she alone was responsible for the war or had, alone, committed acts of barbarity. This need to be looked at by an impartial judge, but that in the meantime Germany would adhere to Wilsonian principle of no indemnities or territorial concessions. Germany would reimburse civilians for damages they had caused, and to rebuild what they had destroyed, but voluntarily and not by slave labor forced on prisoners of war. He proclaimed himself a democrat but remarked: "Democracy did not mean the rule of the masses as such; only the very best men should rule and lead."

Following a Russian broadcast on April 22 declaring that the Soviet Union wanted to re-establish diplomatic relations, Brockdorff - Rantzau told a cabinet session the next day that any discussions should be restricted to private persons developing economic relations until after peace had been concluded with the Allies.

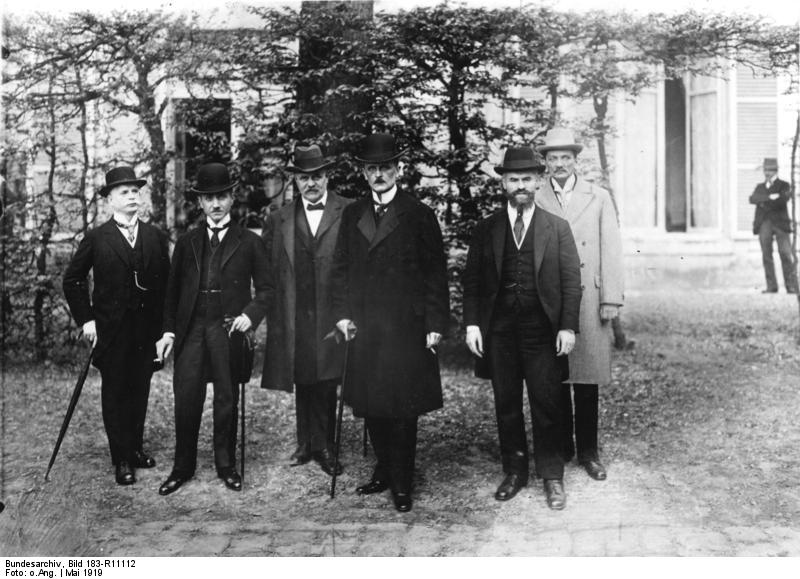

Count von Brockdorff - Rantzau led the German delegation which arrived at Versailles on April 29, and was kept waiting for several days. When the first session began on May 7, French newspapers suggested that this was because it was the anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania. After Georges Clemenceau had accused Germany of being responsible for the war, Brockdorff - Rantzau said that the issue was to reach a lasting peace but admitting that the power of German arms was broken, he nevertheless declared that admission of sole German responsibility for the war would be a lie. He stated that the policy of revenge, as well as the policy of expansion, in disregard of the fight of peoples to determine their own affairs contributed to the sickness of Europe, which reached its crisis in the World War. Russian mobilization took the possibility of curing the disease out of the hands of statesmen and placed the decision into the hand of military force. While he admitted wrongs carried out by the former leaders of Germany, he argued that these and other wrongs committed by other nations should be considered by an objective commission with access to all the archives. The German delegation was then granted seven days to respond to the 440 articles.

In this capacity, Count von Brockdorff - Rantzau attended the signing of the Treaty of Versailles (1919). He had set out to negotiate a peace based on President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points and a request for the union of Austria with Germany. In practice, he found himself trying to defend Germany against the accusation of sole war guilt; he attacked the atrocities of the Allied blockade on Germany following the armistice on November 11, and even made the prediction (which was later borne out), that such a treaty would be impossible to fulfill, and cause continual discontent among the German people.

He was appointed Ambassador to Moscow and played a crucial role in German - Soviet relations until his death from throat cancer in 1928. He developed a close working relationship with Georgy Chicherin, the Soviet People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs from March 1918 to 1930.

Hermann Müller (18 May 1876 - 20 March 1931) was a German Social Democratic politician who served as foreign minister (1919 - 1920) and was twice chancellor of Germany (1920, 1928 - 1930) during the Weimar Republic. In his capacity as foreign minister, he was one of the German signatories of the Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919).

Hermann Müller was born on 18 May 1876 in Mannheim, the son of Georg Jakob Müller (born 1843), a producer of sparkling wine and wine dealer from Güdingen near Saarbrücken, and his wife Karoline (née Vogt, born 1849, died after 1931), originally from Frankfurt am Main. Müller attended the Realgymnasium at Mannheim and, after his father moved to Niederlößnitz in 1888, at Dresden. After his father died in 1892, Müller had to leave school due to financial difficulties and began an apprenticeship at Frankfurt. He worked in Frankfurt and Breslau, and in 1893 joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Heavily influenced by his father and an advocate of Ludwig Feuerbach's views, Hermann Müller was the only German chancellor who was not a member of any religion.

From 1899 to 1906, Müller worked as an editor at the socialist newspaper Görlitzer Volkswacht. He was a member of the local city council (Stadtverordneter) from 1903 to 1906 and party functionary (Unterbezirksvorsitzender). August Bebel nominated him in 1905 (without success) and 1906 (successfully) for membership of the board of the national SPD. At that time, Müller changed from a left wing Social Democrat to a "centrist", who argued against both the "revisionists" and the radical left around Rosa Luxemburg. Together with Friedrich Ebert, Müller succeeded in 1909 in creating a party executive committee that was to deal with internal arguments in between party conventions. Known for his calm, industriousness, integrity and rationality, Müller lacked charisma. In 1909 he tried but failed to prevent Otto Braun's election to the board, laying the foundation for a long-running animosity between the two.

As a result of his foreign language skills, Müller was the representative of the SPD at the Second International, an organization of socialist and labor parties, and at the conventions of socialist parties in other countries in western Europe. In late July 1914, Müller was sent to Paris to negotiate with French socialists over a common stance towards the respective countries' proposals for war loans. No agreement was reached, however, and before Müller was able to report back, the SPD had already decided to support the first war loans in the Reichstag.

During World War I, Müller supported the political truce between Germany's political parties known as the Burgfrieden. He was used by the SPD leadership to deal with arguments with the party's left wing and as an in-house censor for the party newspaper Vorwärts to avoid an outright ban by the military authorities. Müller was close to the group around the leading revisionist Eduard David and supported both the Treaty of Brest - Litovsk with Russia and the entry of the SPD into the government of Max von Baden in October 1918.

First elected in a by-election in 1916, Müller was a

member of the Imperial Reichstag until the collapse of the

German Empire in 1918.

In the German Revolution of 1918-19, Müller was a member of the Greater Berlin Executive Council of Workers and Soldiers (Vollzugsrat der Arbeiter - und Soldatenräte Groß - Berlin) where he represented the position of the SPD leadership, arguing in favor of elections to the Weimar National Assembly. He later published a book on his experience during the revolution.

In January 1919, Müller was elected to the National Assembly. In February 1919, Friedrich Ebert became president of Germany and appointed Philipp Scheidemann as minister president (head of government). The two men had been the joint chairmen of the SPD and now replacements had to be found. Müller and Otto Wels were elected with 373 and 291 out of 376 votes, respectively. Wels focused on internal leadership and organization, whilst Müller was the external representative of the party. In 1919 and 1920 - 28, Müller was also parliamentary party leader first in the National Assembly and then the Weimar Republic Reichstag. He was nominated as chairman of the Reichstag's Committee on Foreign Affairs. After 1920, he was a candidate for the Reichstag for Franconia and changed his name to Müller - Franken to distinguish himself from other members named Müller.

After Scheidemann resigned in June 1919, Müller was asked

to succeed him as head of government but declined. Under

the new Reich Minister President and later Chancellor

Gustav Bauer, Müller became foreign minister on 21 June

1919. In that capacity, he went to Versailles and with

Colonial Minister Johannes Bell signed the Treaty of

Versailles for Germany on 29 June 1919.

After the resignation of the Bauer cabinet, which followed the Kapp - Lüttwitz Putsch in March 1920, Müller accepted Ebert's offer of becoming chancellor and formed a new government that was a continuation of the Weimar Coalition made up of the SPD, German Democratic Party (DDP) and Centre Party. Under his leadership, the government suppressed the left-wing insurgencies such as the Ruhr uprising and urged the disarmament of the paramilitary Einwohnerwehren (Citizens' Defense) demanded by the Allies. The newly created second commission on socialization, which was tasked to examine ways of socializing parts of the German economy, admitted some members from the left wing USPD because Müller felt that it was the only way workers would be willing to accept the commission's decisions. In social policy, Müller's time as chancellor saw the passage of a number of progressive social reforms. A comprehensive war disability system was established in May 1920, while the Law on the Employment of the Disabled of April 1920 stipulated that all public and private employers with more than 20 employees were obligated to hire Germans disabled by accident or war and with at least a 50% reduction in their ability to work. The Basic School Law (passed on 28 April 1920) introduced a common four-year course in primary schools for all German children. Benefits for the unemployed were improved, with the maximum benefit for single males over the age of 21 increasing from 5 to 8 marks in May 1920. Maximum wage scales that were established in April 1919 were also increased.

On 29 March 1920 the Reichstag passed a Reich income tax law, together with a law on corporate tax and a capital yield tax. The Salary Reform Act, passed in April 1920, greatly improved the pay of civil servants. In May 1920, the Reich Office for Labor Allocation was set up as the first Reich wide institution "to allocate labor, administer unemployment insurance and generally manage labor concerns". The Reich Insurance Code of May 1920 provided war wounded persons and dependent survivors with therapeutic treatment and social welfare with the objective of reintegrating handicapped persons into working life. The Cripples' Welfare Act, passed that same month, made it a duty of the public welfare system to assist cripples under the age of 18 to obtain the capacity to earn an income. The Reich Homestead Act, passed in May 1920, sought to encourage homesteading as a means of helping economically vulnerable groups. The Reich Tenant Protection Order of 9 June 1920 sought to check evictions and "an immoderate increase of rental rates", authorizing the states to set up tenancy offices made up of tenants' and owners' representatives, with a judge as chairman to settle disputes concerning rents. As noted by Frieda Wunderlich, they were entitled "to supervise the fixing of rents for all farms". During Müller's last year in office, a number of orders were introduced that "confirmed and defined the protective measures taken in connection with the employment of women in certain work of a particularly dangerous or arduous nature", which included glass works, rolling mills, and iron foundries (through orders of 26 March 1930).

Müller was chancellor only until June 1920, when the

outcome of the first regular election to the Reichstag

resulted in the formation of a new government led by

Constantin Fehrenbach of the Center Party. The SPD

suffered a significant defeat at the polls, with the

number of people voting for them dropping almost by half

compared to the January 1919 election. Discouraged, Müller

only half-heartedly negotiated with the USPD about a

coalition. He was turned down because the USPD was

unwilling to join any coalition including non-socialist

parties and one in which the USPD was not the majority

party. On the other side of the political spectrum, Müller

was opposed to working with Gustav Stresemann's German

People's Party (DVP), considering them a mouthpiece for

corporate interests and doubting their loyalty to the

republican constitution.

The SPD now was in the opposition regarding the domestic agenda of the new government while supporting its foreign policy, in particular regarding reparations to the Allies. Müller was an early advocate of joining the League of Nations and of moving politically closer to the West. He was critical of the Soviet Union's authoritarian system of government, its revolutionary goals and its support for the radical left in Germany. However, he opposed a blockade of the Soviet Union by the western Allies.

Initially, Müller favored diplomatic relations with the Soviets only as far as they would help in preventing the integration of Upper Silesia into the new Polish state. He viewed the Treaty of Rapallo (1922) with the Soviets as a true peace treaty, but one that only had meaning within the context of a successful diplomatic policy towards the western powers, not as an alternative to it. Müller warned against attaching too much hope to the potential economic gains from the treaty, arguing that only the United States would be in a position to provide effective aid for the economic reconstruction of post World War I Europe.

During the two governments led by Joseph Wirth in 1921/22 and in which the SPD participated as part of another Weimar Coalition, Müller demanded as parliamentary leader of the SPD that budget consolidation involve first and foremost higher taxation of wealth rather than of consumption. This led to confrontations with the middle class parties. Similarly, the reunification of SPD and USPD resulted in a move to the left of the new SPD. When the SPD refused to agree to letting the DVP join the existing coalition as desired by the Center Party and DDP, the coalition broke apart in November 1922. The SPD did not participate in the following government of Wilhelm Cuno, which lasted until August 1923.

Recognizing a national emergency when the French seized the Ruhr and inflation spiraled out of control in 1923, Müller brought the SPD into a grand coalition led by Gustav Stresemann (August to November 1923). Differences in economic and social policies strained relations between the SPD and the other members of the coalition. Müller supported the emergency measures taken after October 1923, but the harsh manner which with the Reich government dealt with the governments in Thuringia and Saxony, where the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) was brought into SPD led governments as part of the so-called German October, compared with the lenient handling of the right wing regime in Bavaria, caused the SPD to leave the coalition in November 1923.

At the party convention in 1924, Müller said that the

SPD's stance towards coalitions was based less on

principles than on tactics that were geared towards

foreign policy. During their years in the opposition, the

SPD supported a policy of reconciliation with the western

powers, as exemplified by the Locarno Treaties, which

settled Germany's western borders but left the eastern

ones open, and by Germany's entry to the League of

Nations. After November 1923, the SPD did not participate

in a government again until June of 1928.

In 1928 Prussian Minister President Otto Braun said that he was not interested in becoming chancellor. When the SPD turned out to be the clear winner of the May 1928 elections, the Social Democrats put Müller forward as their candidate. Reich President Paul von Hindenburg would have preferred DVP chairman Ernst Scholz as chancellor but was persuaded to accept Müller by his inner circle, which expected a Social Democratic chancellorship to erode SPD support in the medium term. On 12 June 1928 Hindenburg finally entrusted Müller with forming the government. The other parties proved reluctant to compromise, and it took a personal intervention by Gustav Stresemann for a government to be formed on 28 June 1928. Müller's cabinet, a coalition of Social Democrats, Center Party, DDP, DVP and BVP managed to settle only on a written agreement on the government's policies in the spring of 1929. In particular, domestic policy differences between the SPD and DVP dominated the government's work. Its continued existence was mainly due to the mutual personal esteem between Müller and Foreign Minister Stresemann, who died on 3 October 1929. Relations between the parties were strained by the arguments over construction of the pocked battleship Panzerkreuzer A, in which the SPD forced its ministers to vote against the allocation of funds to the project in the Reichstag even though they had endorsed it in cabinet meetings in order to keep the coalition intact. In addition, the Ruhr iron dispute (Ruhreisenstreit), the "largest and longest lockout Germany had ever experienced", was a bone of contention, as the DVP voted against the Reichstag motion that approved state support for the estimated 200,000 to 260,000 locked out workers.

Financing the budget for 1929 and the external liabilities of the Reich were a huge problem, and reaching an agreement involved negotiating more lenient reparations conditions with the Allies. Müller had been the leader of the delegation to the League of Nations in the summer of 1928 where he – despite a heated argument with French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand over German rearmament – had laid the groundwork for concessions by the Allies. By January 1930, the government had succeeded in negotiating a reduction in reparation payments (the Young Plan, signed in August 1929) and a promise by the Allies to completely withdraw the occupation forces from the Rhineland by May 1930.

Meanwhile, Müller's cabinet also had to deal with diplomatic problems with Poland over trade and the position of ethnic minorities. German - Soviet relations also reached a nadir, as the Soviet government blamed the cabinet for violence between Communist demonstrators and the police in Berlin in May 1929. At that point, the middle class parties were looking for ways to end the coalition with the SPD. The nationalist DNVP and Nazi Party failed to stop the Young Plan via a referendum, and the coalition parties disagreed on the issue of funding unemployment insurance. Müller was unable to participate in the political arena for several months due to a life threatening illness.

Although Müller was able to resume his duties in the fall of 1929, he was physically weakened and unable to control the centrifugal forces at work. The coalition finally fell apart in a disagreement about budgetary issues. After the onset of the Great Depression, the unemployment insurance system required frequent injections of taxpayer money by the Reich, but the parties could not agree on how to raise the funds. Müller was willing to accept a compromise offer by Heinrich Brüning of the Center Party, but he was overruled by the SPD parliamentary group, which refused to make any further concessions. On the suggestion of his advisors, Reich President Hindenburg would not provide Müller's government with the emergency powers available under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, forcing Müller and his cabinet to resign on 27 March 1930.

A number of progressive reforms were implemented under Müller's last government. In 1928, nationwide state-controlled unemployment insurance was established, and midwives and people in the music profession became compulsorily insured under a pension scheme for non-manual workers in 1929. In February 1929, accident insurance coverage was extended to include 22 occupationally induced diseases. That same year, a special pension for unemployed persons at the age of 60 was introduced.

After resigning as chancellor, Müller retired from public

life. Following the elections in September 1930, which saw

massive gains for Adolf Hitler's NSDAP, Müller called on his

party to support Heinrich Brüning's government even

without being part of the coalition. His death in 1931

following a gallbladder operation was seen as a major blow

to the Social Democrats. He died in Berlin and is buried

there at the Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde.

In 1902, Müller married Frieda Tockus. They had one daughter, Annemarie, in 1905. Frieda died several weeks later due to complications from the pregnancy. He remarried in 1909 to Gottliebe Jaeger, and the following year their daughter Erika was born.

Johannes Bell (23 September 1868 - 21 October 1949) was a German jurist and politician from the Center Party. During the Weimar Republic era, he briefly served as Minister of Colonial Affairs, Minister of Transport (1919/20), and as Minister of Justice (1926/27). He was one of the two German representatives who signed the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

Johannes Bell was born on 23 September 1868 in Essen in what was then the Rhine Province of Prussia, as the son of Josef Bell, a land surveyor, and his wife Josefine (née Steuer). A Roman Catholic, Bell married Trude Nünning in 1896.

Bell studied law at Tübingen, Leipzig and Bonn and was awarded a Doctor of Law in 1890.

He started practicing law in Essen in 1894 and in 1900 became a notary. After 1908, Bell was a member of the Prussian diet. From 1911/12 to 1933 (i.e. both in the Empire and in the Weimar Republic), he was a member (and 1920 to 1926 Vice President) of the Reichstag for the Catholic German Center Party or Zentrum. He was also a member of the constituent assemblies, Weimar National Assembly and its Prussian equivalent, the Preußische Landesversammlung.

Bell was a member of the first democratically elected governments of Germany, the Cabinet Scheidemann, Cabinet Bauer and Cabinet Müller I. In February 1919, Bell became Reichskolonialminister (Minister of Colonial Affairs) and he held that post until the ministry was dissolved in November 1919. Together with Hermann Müller (SPD), Bell signed the Treaty of Versailles for Germany on 28 June 1919. After June 1919, he also was Reichsverkehrsminister (Minister of Transport). In this capacity, Bell was instrumental in the creation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, which involved the nationalization of various regional railway lines. He remained in office just long enough to see the National Assembly approve the unification of railways and then resigned in May 1920.

Bell was also a senior figure in the parliamentary group of the Zentrum and the author of numerous publications, making him a well known political figure.

Johannes Bell once again served as a minister of Germany from July 1926 to February 1927 in the cabinet of Wilhelm Marx, as Reichsjustizminister (Minister of Justice) and minister for the occupied territories. After 1930, he was chairman of the Reichstag committee on violations of international law.

After the Nazis seized power in 1933, Bell retired from politics. He died on 21 October 1949 in Würgassen / Weser.