<Back to Index>

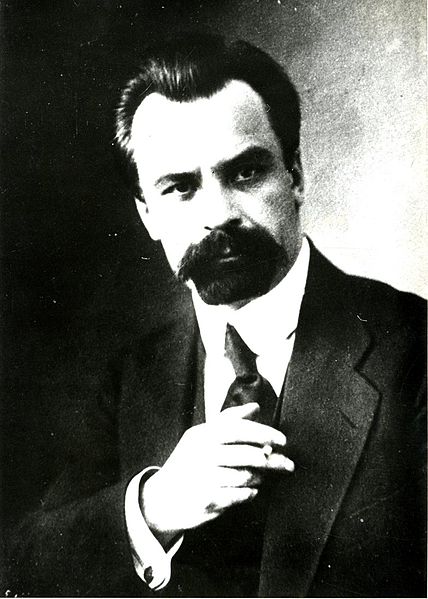

- 1st Chairman of the Directory of Ukraine Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko, 1880

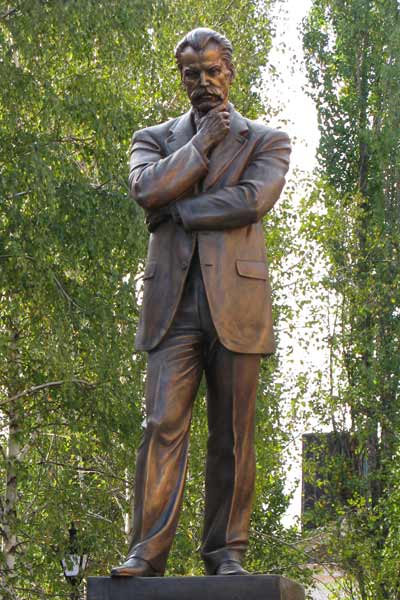

- 2nd Chairman of the Directory of Ukraine Symon Vasylyovych Petliura, 1879

PAGE SPONSOR

Volodymyr Kyrylovych Vynnychenko (Ukrainian: Володимир Кирилович Винниченко, July 26 [O.S. July 14] 1880 - March 6, 1951) was a Ukrainian writer, playwright, artist, political activist and revolutionary, politician and statesman. Vynnychenko is recognized in Ukrainian literature as a leading modernist writer in pre-revolutionary Ukraine, who wrote short stories, novels, and plays, but in Soviet Ukraine his works were proscribed, like that of many other Ukrainian writers, from the 1930s until the mid-1980s. Prior to his entry onto the stage of Ukrainian politics, he was a long time revolutionary activist, who lived abroad in Western Europe from 1906 - 1914. His works reflect his immersion in the Ukrainian and Russian revolutionary milieu, among impoverished and working class people, and among emigres from the Russian Empire living in Western Europe.

Vynnychenko was born in Yelisavetgrad (Kirovohrad), the Kherson Governorate of the Russian Empire in a family of peasants. His father Kyrylo Vasyliovych Vynnychenko earlier in his life was a peasant - serf has moved from a village to the city of Yelisavetgrad where he married a widow Yevdokia Pavlenko (nee: Linnyk). From her previous marriage Yevdokia had three children: Andriy, Maria, and Vasyl, while from the marriage with Kyrylo only one son Volodymyr. Upon graduating from a local public school the Vynnychenko family managed to enroll Volodymyr to the Yelyzavetgrad Male Gymnasium (today is the building of the Ukrainian Ministry of Extraordinary Situations). In later grades of the gymnasium he took part in a revolutionary organization and wrote a revolutionary poem for which was incarcerated for a week and excluded from school. That did not stop him to continue his studying as he was getting prepared for his test to obtain the high school diploma (Matura). He successfully took the test in the Zlatopil gymnasium from which obtained his attestation of maturity.

In 1900 Vynnychenko joined the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP) and enrolled in the law department at Kiev University, but in 1903 he was expelled for participation in revolutionary activities among the Kievan workers and peasants from Poltava and jailed for several months in Lukyanivska Prison. He managed to escape his incarceration. Afterward, he was forcibly drafted into the Russian tsarist army, where he began to agitate soldiers with revolutionary propaganda. Tipped off that his arrest was imminent, Vynnychenko fled to Western Ukraine, Galicia, a region that was part of the Austro - Hungarian Empire. When trying to return to Russian Ukraine in 1903 with revolutionary literature, Vynnychenko was arrested and jailed in Kiev for two years. After his release in 1905, he passed his exams for a law degree in Kiev University.

In 1905 Vynnychenko became a founding and leading member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Worker's Party, which was affiliated with the Russian Social Democratic Party and led by Martov & Lenin. In 1906 Vynnychenko was arrested for a third time, again for his political activities, and jailed for a year; before his scheduled trial, however, the wealthy patron of Ukrainian literature and culture, Yevhen Chykalenko, paid his bail, and Vynnychenko fled the Russian Ukraine again, effectively become an emigre writer abroad from 1907 to 1914, living in Lemberg (Lviv), Vienna, Geneva, Paris, Florence, Berlin. In 1911 Vynnychenko married Rosalia Lifshitz, a Russian Jewish doctor. From 1914 to 1917 Vynnychenko lived near Moscow throughout much of WWI and returned to Kiev in 1917 to assume a leading role in Ukrainian politics.

After the Russian revolution in February 1917, Vynnychenko served as the head of the General Secretariat, a representative executive body of the Russian Provisional Government in Ukraine. He was authorized by the Central Rada of Ukraine (a de facto parliament) to conduct negotiations with the Russian Provisional Government, 1917.

Vynnychenko resigned his post in the General Secretariat on August 13 in protest for the government of Russia declining the Universal of Central Rada. For a brief period he was replaced by Dmytro Doroshenko who composed a new government the next day, yet unexpectedly he requested his resignation as well on August 18. Vynnychenko was offered to return, form a cabinet and redesign the Second Universal to petition a federal union with the Russian Republic. His second government was confirmed by A.Kerensky on September 1.

It is often claimed that political mistakes of Vynnychenko (who was, in effect, prime minister) and Mykhailo Hrushevsky (the head of the Central Rada) cost the newly established Ukrainian People's Republic its independence. Both men were strongly opposed to the creation of the army of the Republic and repeatedly denied the requests by Symon Petliura to use his volunteer forces as the core of a would-be army (Polubotok Regiment Affair).

After the October Revolution and the Kiev Bolshevik Uprising many of his secretaries resigned after the Central Rada disapproved the Bolsheviks actions in Petrograd with the ongoing confrontations in Moscow as well as the other cities in the country (Odessa Soviet Republic). On January 22, 1918, the Ukrainian People's Republic has proclaimed its independents due to the Bolshevik intervention headed the Russian minister Antonov - Ovseyenko. The country was squeezed between the abandoned German - Russian front lines to its western border and the advancing Bolshevik forces of Muravyov along the eastern border. Within days, Mikhail Muravyov manage to invade Kiev forcing the government to evacuate to Zhytomyr whose retreat was secured by the great efforts of the Sich Riflemen. During the evacuation the Ukrainian government managed to secure military assistance in the face of the Central Powers. The government of the Ukrainian People's Republic signed a highly criticized treaty with Germans to repel the Bolshevik forces in exchange for a right to expropriate food supplies. That treaty also required for the Russian SFSR to recognize the Ukrainian People's Republic. Around that time the Vynnychenko's government established an economic agreement with the government of Belarus People's Republic through the Belarus Chamber of Commerce in Kiev. Alas, Vynnychenko's was replaced as well by the Socialist - Revolutionary government of Vsevolod Holubovych.

After the coup d'etat of Hetman Skoropadsky (in collaboration with Germans) in March, 1918, Vynnychenko left Kiev. Later after forming the Directorate of Ukraine he took an active part in organizing a revolt against the Hetman. The revolt was successful and Vynnychenko returned to the capital on December 19, 1918. The Directorate, a temporary central executive committee, proclaimed the restoration of the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Directorate was put in charge until the Ukrainian Constituent Assembly would convene to elect a permanent body of government.

Vynnychenko, unable to restore order and overcome the disagreement among the Directors, stepped down on February 11, 1919. He emigrated the following March.

While in emigration, Vynnychenko wrote Rebirth of a Nation (Вiдродження нацiї, 1919), an account of the Ukrainian revolution up to that point. He argued that the Ukrainian nationalists had made mistakes by ignoring the social question, and that the Bolsheviks had similarly failed to see the importance of national liberation. However, he concluded that the Bolsheviks were beginning to change their position on the Ukrainian nation. For this reason, he began to support reconciliation with the Bolsheviks and returned to Ukraine.

He formed the Foreign Group of the Ukrainian Communist Party, which was mainly made up of other former members of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party, in order to promulgate this position. In June 1920 Vynnychenko himself traveled to Moscow in an attempt to come to an agreement with the Bolsheviks. After four months of unsuccessful negotiation, Vynnychenko had become disillusioned with the Bolsheviks: he accused them of Great Russian Chauvinism and insincerity as socialists. In September 1920 he returned to the emigration, where he revealed his impressions of Bolshevik rule. This split the Foreign Group of the Ukrainian Communist Party: some remained pro - Bolshevik and indeed returned to Soviet Ukraine; others supported Vynnychenko, and with him conducted a campaign against the Soviet regime in their organ Nova doba ("New Era").

Vynnychenko spent the following thirty years in Europe, residing in Germany in the 1920s, then moving to France. As an émigré, Vynnychenko resumed his career as a writer; in 1919 his writing was republished in an eleven volume edition in the 1920s. In 1934 Vynnychenko moved from Paris to Mougins, near Cannes, on the Mediterranean coast, where he lived on a homestead type residence as a self supporting farmer and continued to write, notably a philosophical exposition of his ideas about happiness, Concordism. Vynnychenko called his place Zakoutok. He died in Mougins, near Cannes, France in 1951. Rosalia Lifshitz after her death passed the estate to some Ivanna Vynnykiv - Nyzhnyk (1912 - 1993), who emigrated to France after the World War II and lived with Vynnychenkos since 1948.

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura (Ukrainian: Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; Russian: Симо́н Васи́льевич Петлю́ра; also known as Simon Petlura, Symon Petlura, or Symon Petlyura, May 10, 1879 - May 25, 1926) was a publicist, writer, journalist, Ukrainian politician, statesman and national leader who led Ukraine's struggle for independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917.

During the period of Ukrainian independence in 1918 - 1920, he was Head of the Ukrainian State.

On May 25, 1926 Petliura was slain with five shots from a handgun in the broad daylight by the Russian Jewish anarchist Sholom Schwartzbard in the center of Paris. According to several political parties in Ukraine, such as the Ukrainian People's Party, Schwartzbard was a Soviet spy (NKVD). The fact that the assassination of Petliura was a special operation of GPU was acknowledged by a KGB operative and World War II veteran Peter Deriabin, who defected to the West, during his speech to US Congress.

Petliura was born on May 10, 1879, in a suburb of Poltava, Ukraine, the son of Vasyl Petliura and Olha (née Marchenko), of Cossack class. Cossack, as opposed to peasant heritage, allowed certain privileges regarding land ownership, taxes and access to education in the Russian Empire, of which most of Ukraine was then part. Petliura's initial education was obtained in parochial schools, and he planned to become an Orthodox priest.

During the years 1895 - 1901 in the Russian Orthodox Seminary in Poltava, Petliura joined the Ukrainian Revolutionary Party (RUP) in 1898. When his membership in RUP was discovered in 1901, he was expelled from the seminary. In 1902, under threat of arrest, he moved to Yekaterinodar in the Kuban where he worked for 2 years initially as a schoolteacher and later in the archives of the Kuban Cossack Host where he helped organize over 200 thousand documents. In December 1903, he was arrested for organizing a RUP branch in Yekaterinodar and for publishing inflammatory anti - tsarist articles in the Ukrainian press outside of Imperial Russia. He was released in March 1904, moving briefly to Kiev and then emigrating to the Western Ukrainian city of Lviv then in the Austro - Hungarian Empire.

In Lviv, Petliura lived under the name of Sviatoslav Tagon working alongside Ivan Franko, Volodymyr Hnatiuk publishing and working as an editor for the "Literaturno - Naukovy Zbirnyk" Journal (Literary - Scientific Collection), the Shevchenko Scientific Society and as a co-editor of "Volya" magazine. He contributed numerous articles to the Ukrainian language press in Galicia.

At the end of 1905, after amnesty was declared, Petliura returned briefly to Kiev but soon moved to the Russian capital of Petersburg in order to publish the socialist - democratic monthly magazine Vil’na Ukrayina (Free Ukraine). After Russian censors closed this magazine in July 1905, he moved back to Kiev where he worked for the magazine Rada (Council). In 1907 - 09 he became the editor of the literary magazine Slovo (Word) and co-editor of Ukrayina (Ukraine).

Because of the closure of these publications by the Russian Imperial authorities, Petliura was forced to once again move from Kiev to Moscow in 1909, where he worked briefly as an accountant. There, he married Olha Bilska (1885 - 1959), with whom he had a daughter, Lesia (1911 - 42). From 1912 he was a co-editor of the influential Russian language journal Ukrainskaya zhizn’ (Ukrainian life) until May 1917.

As the editor of numerous journals and newspapers, Petliura published over 15 000 critical articles, reviews, stories and poems under an estimated 120 nom - de - plumes. His prolific work in both the Russian and Ukrainian languages helped shape the mindset of the Ukrainian population in the years leading up to the Revolution in both Eastern and Western Ukraine. His prolific correspondence was of great benefit when the Revolution broke out in 1917, as he had contacts throughout Ukraine.

As the Ukrainian language had been outlawed in the Russian Empire by the Ems Ukaz of 1876, Petliura found more freedom to publish Ukraine oriented articles in Saint Petersburg than in Ukraine. There, he published the magazine "Vil'na Ukrayina" (Independent Ukraine, Ukrainian: Вільна Україна) until July 1905. Tsarist censors, however, closed this magazine, and Petliura moved back to Kiev.

In Kiev, Petliura first worked for "Rada" (Council: Ukrainian - Радa). In 1907 he became editor of the literary magazine "Slovo" (The Word: Ukrainian - Слово). Also, he co-edited the magazine "Ukrayina" (Ukraine, Ukrainian: Україна).

In 1909, these publications were closed by Russian imperial police, and Petliura moved back to Moscow to publish. There, he was co-editor of the Russian language magazine "Ukrayinskaya Zhizn" (Ukrainian Life) to familiarize the local population with news and culture of what was known as Malorossia. He was chief editor with this publication from 1912 to 1914. In Moscow he married his wife Olha Bilska in 1915 (later she was also known as her husband under the surname of Marchenko). There, in Moscow was born the daughter of Peliura, Lesia (Olesia).

In Paris, Petliura continued the struggle for Ukrainian independence as a publicist. In 1924, Petliura became the editor and publisher of the weekly journal "Tryzub" (Trident: Ukrainian - Тризуб). He contributed to this journal using various pen names, including V. Marchenko, and V. Salevsky.

Petliura's correspondence with all the noted Ukrainian literary figures of the time and his many articles addressing the problems of Ukrainian self awareness and cultural development were unavailable during the Soviet period and have only recently been made available for study. Previously all the journals which he published and edited were only available in main Academic library in Moscow, in the vaults with restricted access. Currently scholarship in Petliura's monumental legacy is being collected, published and carefully studied. New documents continue to be discovered.

Petliura attended the first All - Ukrainian Army Congress held in Kiev in May 1917 as a delegate, where he was elected head of the Ukrainian General Army Committee on May 18. With the proclamation of the Ukrainian Central Council on June 28, 1917, Petliura became the First Secretary for military matters. Disagreeing with the politics of the then Head of the General Secretariat Volodymyr Vynnychenko, Petliura left the government and became the head of the Haydamatskyj Kish of Sloboda Ukraine (in Kharkiv), a military formation that in January - February 1918 was forced back to protect Kiev during the Uprising on the Arsenal Plant and prevent capturing the capital by the Bolshevik Red Guard.

After the Hetmanate Putsch (April 28, 1918), Petliura was arrested by the Skoropadsky administration and spent four months incarcerated in Bila Tserkva.

After his release, Petliura participated in the anti - Hetmanate putsch and became a member of the Directorate of Ukraine as the Chief of Military Forces. With the fall of Kiev and the emigration of Vynnychenko from Ukraine, Petliura became the leader of the Directorate in February 1919. In his capacity as head of the Army and State, he continued to fight both Bolshevik and White forces in Ukraine for the next ten months.

With the outbreak of hostilities between Ukraine and Soviet Russia in January 1919, and with Vynnychenko's emigration, Petliura ultimately became the leading figure in the Directorate. During the winter of 1919 the Petliura army lost most of Ukraine (including Kiev) to Bolsheviks and by March 6 relocated to Podolie. In the spring of 1919 he managed to extinguished a coup d'etat led by Volodymyr Oskilko who saw Petliura cooperating with socialists such as Borys Martos. During the course of the year, Petliura continued to defend the fledgling republic against incursions by the Bolsheviks, Anton Denikin's White Russians, and the Romanians. By autumn of 1919, most of Denikin's White Russian forces were defeated - in the meantime, however, the Bolsheviks had grown to become the dominant force in Ukraine.

Petliura withdrew to Poland December 5, 1919, which had previously recognized him as the head of the legal government of Ukraine. In April 1920, as head of the Ukrainian People's Republic, he signed an alliance in Warsaw with the Polish government, agreeing to a border on the River Zbruch and recognizing Poland's right to Galicia in exchange for military aid in overthrowing the Bolshevik regime. Polish forces, reinforced by Petliura's remaining troops (some two divisions), attacked Kiev on May 7, 1920 in what became a turning point of the 1919 - 21 Polish - Bolshevik war. Following initial successes, Piłsudski's and Petliura's forces were pushed back to the Vistula River and the Polish capital, Warsaw. The Polish Army managed to defeat the Bolshevik Russians, but were unable to secure independence for Ukraine. Petliura directed the affairs of the Ukrainian government - in - exile from Tarnów and when the Soviet Union requested Petliura's extradition from Poland, the Poles engineered his "disappearance," secretly moving him from Tarnów to Warsaw.

Bolshevik Russia persistently demanded that Petliura be handed over. Protected by several Polish friends and colleagues, such as Henryk Józewski, with the establishment of the Soviet Union on December 30, 1922, Petliura, in late 1923 left Poland for Budapest, then Vienna, Geneva and finally settled in Paris in early 1924. Here he established and edited the Ukrainian language newspaper Tryzub (Trident).

During his time as leader of the Directorate, Petliura was active in supporting Ukrainian culture both in Ukraine and abroad.

Petliura introduced the awarding of the title "People's Artist of Ukraine" to artists who had made significant contributions to Ukrainian culture. A similar title award was continued after a significant break under the Soviet regime. Among those who had received this award was blind kobzar Ivan Kuchuhura Kucherenko.

He also saw the value in gaining international support and recognition of Ukrainian arts through cultural exchanges. Most notably, Petliura actively supported the work of cultural leaders such as the choreographer Vasyl Avramenko, conductor Oleksander Koshetz and bandurist Vasyl Yemetz, to allow them to travel internationally and promote an awareness of Ukrainian culture. Koshetz created the Ukrainian Republic Capella and took it on tour internationally, giving concerts in Europe and the Americas. One of the concerts by the Capella inspired George Gershwin to write "Summertime", based on the lullaby Oi Khodyt Son Kolo Vikon (The dream passes by the Windows). All three musicians later emigrated to the United States.

In Paris, Petliura directed the activities of the government of the Ukrainian National Republic in exile. He launched the weekly Tryzub, and continued to edit and write numerous articles under various pen names with an emphasis on questions dealing with national oppression in Ukraine. These articles were written with a literary flair. The question of national awareness was often of significance in his literary work.

Petliura's articles had a significant impact on the shaping of Ukrainian national awareness in the early 20th century. He published articles and brochures under a variety of noms de plume, including V. Marchenko, V. Salevsky, I. Rokytsky and O. Riastr.

Anti - Jewish pogroms accompanied the Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Russian Civil War. The Ukrainian state promised Jews full equality and autonomy, and Arnold Margolin, a Jewish minister in Petliura's government, declared in May 1919 that the Ukrainian government had given Jews more rights than they enjoyed in any other European government. However, Petliura lost control over most of his armed forces, who then engaged in killing Jews. During Petliura's term as Head of State (1919 - 20), pogroms continued to be perpetrated on Ukrainian ethnic territory, and the number of Jews killed during the period is estimated to be from 35,000 to 50,000.

The debate about Petliura's role in the pogroms has been a topic of dispute since Petliura's assassination and Schwartzbard's trial. In 1969, the Journal of Jewish Studies published two opposing views by scholars Taras Hunczak and Zosa Szajkowski, views still frequently cited.

Some historians claim that Petliura, as the head of the government, did not do enough to stop the pogroms. They suggest this lack of activity knowingly encouraged them, thus strengthening his base of support among his soldiers, commanders and the peasant population at large, by appealing to antisemitic sentiments. They also suggest that many of the atrocities were committed by the forces directly under the command of the Directorate and loyal to Petliura. According to a Jewish former member of the Ukrainian government's cabinet, Solomon Goldelman, Petliura was afraid to punish officers or soldiers engaged in crimes against Jews for fear of losing their support. Nevertheless, Goldelman consistently defended Petliura and his record. Petliura is said to have once said, "it is a pity that pogroms take place, but they uphold the discipline of the army.

Historians have pointed out that Petliura himself never demonstrated any personal antisemitism, and it is documented that he actively sought to halt anti - Jewish violence on numerous occasions, introducing capital punishment for the crime of pogroming. Taras Hunczak of Rutgers University writes that "to convict Petliura for the tragedy that befell Ukrainian Jewry is to condemn an innocent man and to distort the record of Ukrainian - Jewish relations".

Because the Soviet Union saw Petliura and Ukrainian nationalism as a threat, it was in its interest to tarnish his reputation. A propaganda campaign to this end included accusations of anti - Jewish crimes. Hunczak insists that "Petliura's own personal convictions render such responsibility highly unlikely, and all the documentary evidence indicates that he consistently made efforts to stem pogrom activity by UNR troops."

In 1921 Ze'ev Jabotinsky, the father of Revisionist Zionism, signed an agreement with Maxim Slavinsky, Petliura's representative in Prague, regarding the formation of a Jewish gendarmerie which was to accompany Petliura’s putative invasion of Ukraine, and would protect the Jewish population from pogroms. This agreement did not materialize, and Jabotinsky was heavily criticized by most Zionist groups. Nevertheless he stood by the agreement and was proud of it.

On May 25, 1926, while walking on rue Racine, near Boulevard Saint - Michel, Petliura was approached by Sholom Schwartzbard. Schwartzbard asked him in Ukrainian, "Are you Mr. Petliura?" Petliura did not answer but raised his walking cane. Then, as Schwartzbard claimed in court, he pulled out a gun and shot him five times. Some state two more shots were fired after Petliura was lying on the ground. That is how Schwartzbard described the incident:

"When I saw him fall I knew he had received five bullets. Then I emptied my revolver. The crowd had scattered. A policeman came up quietly and said: 'Is that enough?' I answered: 'Yes.' He said: 'Then give me your revolver.' I gave him the revolver, saying: 'I have killed a great assassin.' "When the policeman told me Petliura was dead I could not hide my Joy. I leaped forward and threw my arms about his neck."

Schwartzbard was claiming that he was walking around Paris with Petliura's photo in one pocket and his handgun in another, peering in the faces of the Paris residents just to find his victim.

Schwartzbard was a Russian anarchist of Jewish descent born in on the territory of Little Russia (today Ukraine). He participated in the Jewish self defense of Balta, for which the Russian Tsarist government sentenced him to 3 months in prison for "provoking" the Balta pogrom, and was twice convicted for taking part in anarchist "expropriation" (burglary) and bank robbery in Austro - Hungary. He later joined the French Foreign Legion (1914 - 1917) and was wounded in the Battle of the Somme. It is reported that Schwartzbard told famous fellow anarchist leader Nestor Makhno in Paris that he was terminally ill and expected to die, and that he would take Petliura with him; Makhno forbade Schwartzbard to do so.

The French Secret service had been keeping an eye out on Schwartzbard from the time he had surfaced in the French capital and had noted his meetings with known Bolsheviks. During the trial the German special services also informed their French counterparts that Schwartzbard had assassinated Petliura on the orders of Galip, an emissary of the Union of Ukrainian Citizens. He had received orders from a former chairman of the Soviet Ukrainian government and current Soviet Ambassador to France, Christian Rakovsky, an ethnic Bulgarian and a revolutionary leader from Romania. The act was consolidated by Mikhail Volodin, who arrived in France August 8, 1925 and who had been in close contact with Schwartzbard.

Schwartzbard's parents were among fifteen members of his family murdered in the pogroms in Odessa. The core defense at the Schwartzbard trial was — as presented by the noted jurist Henri Torres — that he was avenging the deaths of more than 50,000 Jewish victims of the pogroms, whereas the prosecution (both criminal and civil) tried to show that:

- (i) Petliura was not responsible for the pogroms and

- (ii) Schwartzbard was a Soviet agent.

Both sides brought on many witnesses, including several historians. A notable witness for the defense was Khaye Greenberg (aged 29), a local nurse who survived the Proskurov pogroms and testified about the carnage. She never said that Petliura personally participated in the event, but rather some other soldiers who did said that they were directed by Petliura. The pogrom in Proskurov was really taken place and was led by Otaman Semesenko on his own initiative on February 15, 1919 (soon after the fall of Hetmanate). Two weeks later Petliura orders denouncing the event were published in newspapers. Because of a difficult situation the execution of Semesenko was postponed until November 1920. Several former Ukrainian officers testified for the prosecution.

After a trial lasting eight days the jury acquitted Schwarzbard.

Petliura is buried alongside his wife and daughter in the Cimetičre du Montparnasse in Paris, France.

Petliura's two sisters, Orthodox nuns who had remained in Poltava, were arrested and shot in 1928 by the NKVD (the Soviet secret police). It is claimed that in March 1926 Vlas Chubar (the Russian Commissar to Ukraine), in a speech given in Kharkiv and repeated in Moscow, warned of the danger Petliura represented to Soviet power. It is after this speech that the command was allegedly given to assassinate Petliura.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, previously restricted Soviet archives have allowed numerous politicians and historians to review Petliura's role in Ukrainian history. Some consider him a national hero who strove for the independence of Ukraine. Several cities, including Kiev, the Ukrainian capital and Poltava, the city of his birth, have erected monuments to Petliura, with a museum complex also being planned in Poltava. To mark the 80th anniversary of his assassination, a twelve volume edition of his writings, including articles, letters and historic documents, has been published in Kiev by the Taras Shevchenko University and the State Archive of Ukraine. In 1992 in Poltava a series of readings known as "Petlurivski chytannia" have become an annual event, and since 1993 these take place annually at Kiev University.

In June 2009 the Kiev city council renamed Komintern's Street (located in the Shevchenkivskyi Raion) into Symon Petliura Street to commemorate the occasion of his 130th birthday anniversary.

In Israel and the Jewish world Petliura is mostly remembered by some as the leader in charge of Ukraine when pogroms took place (Yad Vashem and the writing on the street sign honoring Schwartzbard in Beersheba). One of Ukrainian - Jewish leaders in independent Ukraine wrote that "Petliura did not want or was not able to defend Ukrainian Jews from his own army".

Recently uncovered documents and letters to prominent Jewish community leaders demonstrate Petliura's support for the re-establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. In a "in the name of" the Jewish population of Ukraine, former Jewish affairs minister Pinchas Krasny thanked Petliura for his support for the vote in the League of Nations of July 24, 1922 regarding the formation of a Jewish state in Palestine. A further reflection regarding Petliura's position regarding Jews is demonstrated by another interesting fact. In exile, as the Head Otаman of the Ukrainian forces he was functioning in great material difficulties. In February 1921 he assigned Jewish refugees from Ukraine in Poland 15 thousand Polish Marks in aid.

In the Western Ukrainian diaspora, Petliura is remembered as a national hero, a fighter for Ukrainian independence, a martyr, who inspired hundreds of thousands to fight for an independent Ukrainian state. He has inspired original music, and youth organizations.

During the revolution Petliura became the subject of numerous folk songs, primarily as a hero calling for his people to unite against foreign oppression. His name became synonymous with the call for freedom. 15 songs were recorded by the ethnographer rev. prof. K. Danylevsky. In the songs Petliura is depicted as a soldier, in a manner similar to Robin Hood, mocking Skoropadsky and the Bolshevik Red Guard.

News of Petliura’s assassination in the summer of 1926 was marked by numerous revolts in eastern Ukraine particularly in Boromlia, Zhehailivtsi, (Sumy province), Velyka Rublivka, Myloradov (Poltava province), Hnylsk, Bilsk, Kuzemyn and all along the Vorskla River from Okhtyrka to Poltava, Burynia, Nizhyn (Chernihiv province) and other cities. These revolts were brutally pacified by the Soviet administration. The blind kobzars Pavlo Hashchenko and Ivan Kuchuhura Kucherenko composed a duma (epic poem) in memory of Symon Petliura. To date Petliura is the only modern Ukrainian politician to have a duma created and sung in his memory. This duma became popular among the kobzars of left bank Ukraine and was sung also by Stepan Pasiuha, Petro Drevchenko, Bohushchenko and Chumak.

The Soviets also tried their hand at portraying Petliura through the arts in order to discredit the Ukrainian national leader. A number of humorous songs appeared in which Petliura is portrayed as a traveling beggar whose only territory is that which is under his train carriage. A number of plays such as the “Republic on wheels” by Mamontov and the opera “Shchors” by Boris Liatoshinsky and “Arsenal” by Georgy Maiboroda portray Petliura in a negative light, as a lackey who sold out Western Ukraine to Poland, often using the very same melodies which had become popular during the fight for Ukrainian Independence in 1918.

Petliura continues to be portrayed by the Ukrainian people in its folk songs in a manner similar to Taras Shevchenko and Bohdan Khmelnytsky. He is likened to the sun which suddenly stopped shining.