<Back to Index>

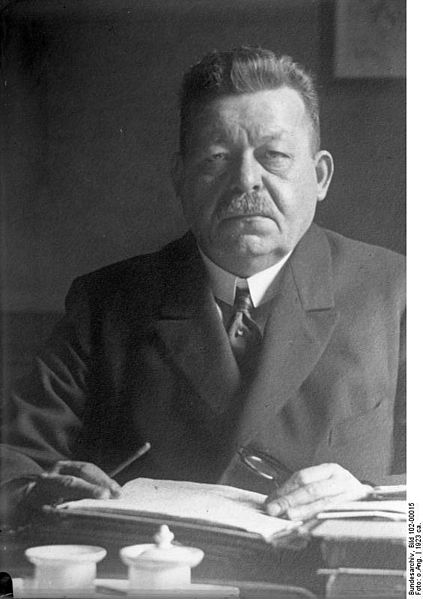

- 1st President of

Germany Friedrich

Ebert, 1871

PAGE SPONSOR

Friedrich Ebert (February 4 1871 - February 28 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), who served as the first President of Germany from 1919 to 1925.

When Ebert was elected as the leader of the SPD after the death of August Bebel, the party members of the SPD were deeply divided because of the party's support for World War I. A moderate social democrat, Ebert supported the Burgfrieden and tried to isolate the war opposition in the party. After the war and the end of the monarchy he served as the first President of Germany from 1919 until his death in office. Before being elected as President, he briefly served as Chancellor during the last months of the German Empire. After he was announced as the new President, the government intervened together with the army and right wing Freikorps against the leftist uprisings, which resulted in the death of several left politicians and ended the partnership of the SPD in government with the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD).

After that he changed his politics to a “policy of

compensating“ between the left and the right, between the

workers and the enterprises. For that he followed a policy

of brittle coalitions. This resulted in some problems, for

example the SPD agreed during the crisis of 1923 to an

extension of the work time without extra payment for the

workers, but the conservative parties hadn’t agreed to

also introduce taxes for the rich as an compensation. His

death, which resulted in the monarchist Paul von

Hindenburg as his Presidential successor, is seen as an

important break in the Weimar Republic, which ended less

than a decade later.

Born in Heidelberg as the son of a tailor, he himself was trained as a saddle-maker. After he had become a journeyman he migrated, according to the German custom, from place to place in Germany, seeing the country and learning fresh details of his trade until he finally settled at Bremen. There he became interested in the agitation of the Social Democratic Party, obtained in 1893 an editorial post on the socialist Bremer Volkszeitung and in 1900 was appointed a trade union secretary and ultimately elected a member of the Bremen Bürgerschaft (comitia of citizens) as representative of the Social Democratic Party. He became a leader of the "moderate" wing of the Social Democratic Party, becoming Secretary-General in 1905, and party chairman in 1913. In 1912 he was elected as a Member of the Reichstag (parliament of Germany) for the constituency of Elberfeld - Barmen (now part of Wuppertal).

In August 1914, Ebert led the party to vote almost unanimously in favor of war loans, accepting that the war was a necessary patriotic, defensive measure, especially against the autocratic regime of the Tsar in Russia. The party's stance, under the leadership of Ebert and other "moderates" like Philipp Scheidemann, in favor of the war with the aim of a compromise peace, eventually led to a split, with those radically opposed to the war leaving the S.P.D. in early 1917 to form the U.S.P.D. For similar reasons several left wing members of parliament had already distanced themselves from the party in 1916. Later they called themselves "Spartacists".

When it became clear that the war was lost, a new government was formed by Prince Maximilian of Baden which included Ebert and other members of the S.P.D. in October 1918. Following the outbreak of the German Revolution, Prince Max resigned on November ninth, and handed his office over to Ebert. Prince Max also declared that the Kaiser had abdicated. Ebert favored retaining the monarchy under a different ruler ("If the Kaiser does not abdicate, the social revolution is inevitable. But I do not want it, I even hate it like sin" he had said to Max von Baden on November seventh). On the same day, how ever, Scheidemann proclaimed the German Republic, in response to the unrest in Berlin and in order to counter a declaration of the "Free Socialist Republic" by Karl Liebknecht later that day. Ebert reproached him: "You have no right to proclaim the Republic!" By this he meant that the decision was to be made by an elected national assembly, even if that decision might be the restoration of the monarchy.

Scheidemann's proclamation ended the German monarchy, and an entirely Socialist provisional government based on workers' councils took power under Ebert's leadership.

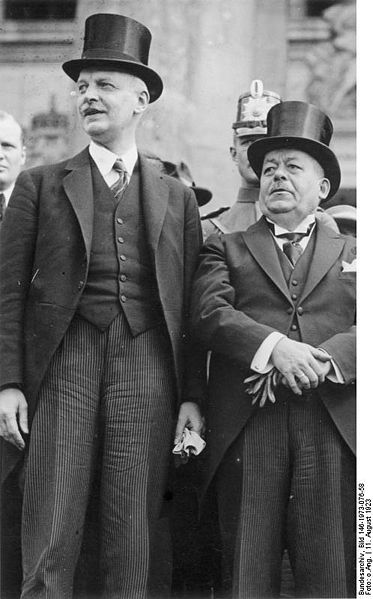

Ebert led the new government for the next several months. He used the army under the command of Minister of Defense Gustav Noske and also Freikorps (paramilitary organizations of former soldiers) to suppress the so-called Spartacist uprising against the establishment of a parliamentary democracy. Spartacist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were murdered by members of the Freikorps. On February eleventh, 1919, five days after the Constituent Assembly convened in Weimar, Ebert was elected to be the first president of the German Republic.

In 1920, the German workers protected his government from

the right-wing Kapp Putsch of some Freikorps elements by

means of a nation wide general strike. The armed forces

Reichswehr remained neutral and did not defend the

republic. Nevertheless, the government used the army and

parts of the Freikorps in order to suppress a left wing

workers' rebellion in Germany's main industrial area, the

Ruhr district in north-west Germany. Thousands of people

were killed.

Participants in the Kapp Putsch were treated leniently. The judiciary in the Weimar Republic was "blind in the right eye". Some of the Freikorps already used the swastika as their symbol of resistance against the "red pack" at the time, and many of them as well as right wing members of the Reichswehr would later become influential National Socialists.

Ebert suffered from gallstones and frequent bouts of cholecystitis. He became acutely ill in mid February 1925, from what was believed to be influenza. His condition deteriorated over the following two weeks, and at that time he was thought to be suffering from another episode of gallbladder disease. He became acutely septic on the night of 23 February, and underwent an emergency appendectomy (which was performed by August Bier) in the early hours of the following day for what turned out to be appendicitis. He died of septic shock four days later, at 54 years of age.

Vicious attacks by Ebert's right wing adversaries, including slander and ridicule, were often condoned or even supported by the judiciary when the president turned to the courts. The constant necessity to defend himself against those attacks also undermined his health.

Ebert‘s politics of compensating during the Weimar

Republic is seen as an important archetype in the S.P.D.

Today, the S.P.D.-associated Friedrich Ebert Foundation,

Germany's largest and oldest party-affiliated foundation,

which, among other things, promotes students of

outstanding intellectual ability and personality, is named

after Ebert.

Ebert remains a somewhat controversial figure to this day. While the S.P.D. recognizes him as one of the founders and keepers of German democracy whose death in office in February 1925 was a great loss, communists and others on the left argue that he paved the way for national socialism by supporting the Freikorps and their suppression of violent worker uprisings.

Elements of the Freikorps, which consisted of World War I veterans, maintained that the German working class, supported by the S.P.D., was responsible for Germany's defeat in World War I. The alleged proof of this Dolchstoßlegende was found in a number of strikes during 1917 and 1918 which had partly disrupted production in the Imperial German armaments industry. The aim of the striking workers and their socialist allies was said to have been to turn the German Empire into a Soviet Socialist Republic. Most historians, however, say that military defeat was inevitable after the U.S. had joined the war against Germany. In November 1918, a delegation of members of parliament represented Germany in the ceasefire negotiations at the request of the military leadership after the generals had decided that the war could no longer be won. Critics say that thus the politicians exactly played the role that the military wanted them to play. Ebert later on even cooperated with the generals in order to prevent the country from falling into chaos, as he saw it.

Some historians have defended Ebert's actions as unfortunate but inevitable if the creation of a socialist state on the model that had been promoted by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and the communist Spartacus Group was to be prevented. Leftist historians like Bernt Engelmann as well as mainstream ones like Sebastian Haffner on the other hand, have argued that organized communism was not yet politically relevant in Germany at the time. However, the actions of Ebert and his Minister of Defense, Gustav Noske, against the insurgents contributed to the radicalization of the workers and to increasing support for communistic ideas.

Although the Weimar constitution (which Ebert signed into law in August 1919) provided for the establishment of workers' councils on different levels of society, they did not play a major part in the political life of the Weimar Republic. Ebert always regarded the institutions of parliamentary democracy as a more legitimate expression of the will of the people; workers' councils, as a product of the revolution, were only justified in exercising power for a transitive period. "All power to all the people!" was the slogan of his party, in contrast to the slogan of the far left, "All power to the (workers') councils!". In Ebert's opinion only reforms, not a revolution, could advance the causes of democracy and socialism. So he has been called a traitor by the far left, paving the way for the ascendancy of the far right and even of Hitler, whereas those who think his policies were justified claim that he saved Germany from Bolshevik excesses.