<Back to Index>

- Secretary of State

for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Labour Party

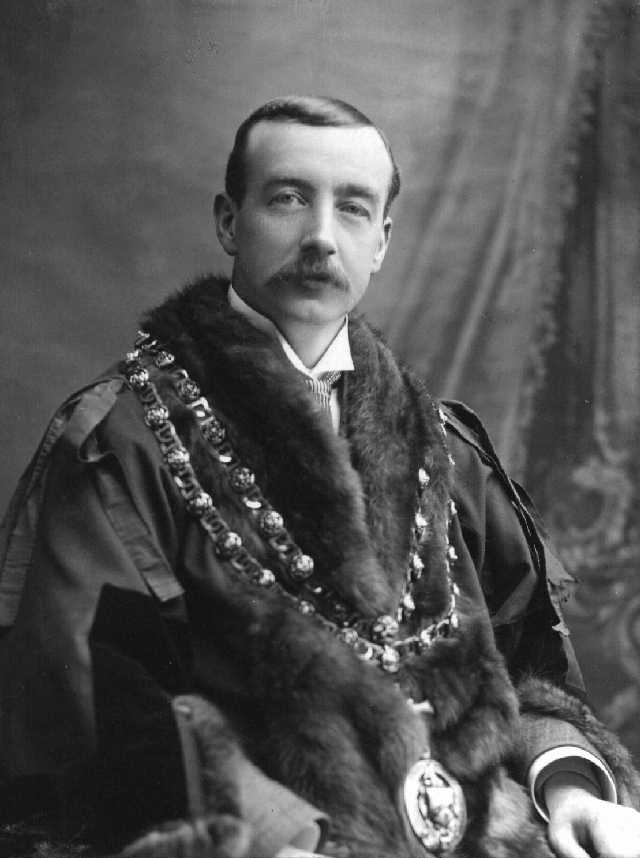

Arthur Henderson, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 - 20 October 1935) was a British iron molder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and served three terms as the Leader of the Labour Party. He was popular among his colleagues, who called him "Uncle Arthur" in acknowledgement of his integrity, devotion to the cause and unperturbability. He was a transition figure whose policies were closer to the Liberal Party for the trades unions rejected his emphasis on arbitration and conciliation and thwarted his goal of unifying the Labour Party and the trades unions.

Arthur Henderson was born at 10 Paterson Street, Anderston, Glasgow, Scotland in 1863, the illegitimate son of Agnes Henderson, a domestic servant. Agnes later married and she and her young son moved to Newcastle upon Tyne in the North East of England.

Henderson worked in a locomotive factory from the age of

12. After finishing his apprenticeship at seventeen, he

moved to Southampton for a year and then returned to work

as an iron molder (a

type of foundryman) in

Newcastle - upon - Tyne. He converted to Methodism (having

previously been a Congregationalist) in 1879. This had a

major impact on Henderson and he became a lay preacher. In 1884,

Henderson lost his job and concentrated on his education

and preaching commitments.

By 1892, Henderson had entered the complex world of Trade Union politics, when he was elected as a paid organizer for the Iron Founders Union, and was also a representative on the North East Conciliation Board.

Henderson believed that strikes caused more harm than

they were worth, and tried to avoid them whenever he

could. For this reason he opposed the formation of the

General Federation of Trade Unions, as he was convinced it

would lead to more strikes.

In 1900, Henderson was one of the 129 trade union and socialist delegates, who passed Keir Hardie's motion to create the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), and in 1903, Henderson was elected treasurer of the LRC, and was also elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Barnard Castle following a by-election.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the Labour Party and won 29 seats in the general election of that year (which was a landslide victory for the Liberal Party).

In 1908, when Hardie resigned as Leader of the Labour

Party, Henderson was elected to replace him, and was

leader for two fairly quiet (from Labour's perspective)

years, before resigning in 1910.

In 1914, the First World War broke out, and the then Labour leader, Ramsay MacDonald, resigned in protest. Henderson was elected to replace him, and in 1915, following Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith's decision to create a coalition government, became the first member of the Labour Party to become a member of the Cabinet, as President of the Board of Education.

In 1916, David Lloyd George forced Asquith to resign and

replaced him as Prime Minister. Henderson became a member

of the small War Cabinet with the job of Minister without Portfolio.

Other labor and union representatives to join Henderson in

Lloyd George's coalition government were; John Hodge and

George Barnes. John Hodge became Minister of Labour whilst

Barnes became Minister of Pensions. Henderson resigned in

August 1917 when his idea for an international conference

on the war was voted down by the rest of the cabinet;

shortly afterwards he resigned as Labour leader.

Henderson lost his seat in the "coupon election" of 14 December 1918, an election announced within twenty four hours of the end of hostilities in World War I that resulted in a landslide victory for a coalition formed by presiding Prime Minister Lloyd George. Henderson returned to Parliament in 1919 after winning a by-election in Widnes. After his election, he became Labour's chief whip, only to lose his seat in the 1922 general election.

Again, he returned to Parliament via a by-election, this time representing Newcastle East, however he lost this seat in the 1923 general election, but returned to Parliament two months later after winning a by-election in Burnley. He was appointed Home Secretary in the first ever Labour government (led by MacDonald). This government was defeated in 1924, and lost the following election.

Henderson was re-elected in 1924, and he refused to challenge MacDonald for the party leadership, despite calls from other MPs to do just that. Worried about factionalism in the Labour Party, he published a pamphlet called Labour and the Nation, in which he attempted to clarify the Labour Party's goals.

In Moscow Vladimir Lenin held him in very low regard. In a 10 February 1922, letter to the Soviet Foreign Affairs Commissar Georgy Chicherin in relation to the Genoa Conference, Lenin wrote pejoratively:

"Henderson is as stupid as Kerensky, and for this reason he is helping us....

Furthermore. This is ultrasecret. It suits us that Genoa be wrecked... but not by us, of course. Think this over with Litvinov and Ioffe and drop me a line. Of course, this must not be mentioned even in secret documents. return this to me, and I will burn it. We will get a loan better without Genoa, if we are not the ones that wreck Genoa. We must work out cleverer maneuvers so that we are not the ones that wreck Genoa. For example, the fool Henderson and Co. will help us a lot if we cleverly prod them....

In 1929, Labour formed another minority government, and MacDonald appointed Henderson as Foreign Secretary, a position Henderson used to try to reduce the tensions that had been building up in Europe since the end of the War. Diplomatic relations were re-established with the USSR and the League of Nations was given Britain's full support. The government was able to function properly, even without a parliamentary majority. However this did not last. The Great Depression plunged the government into a terminal crisis.Everything is flying apart for them. It is total bankruptcy (India and so on). We have to push a falling one unexpectedly, not with our hands."

The crisis began in 1931 when a key committee discovered that the budget was facing a serious deficit. This generated a crisis of confidence in the British financial system which threatened the Pound's position on the Gold Standard. The Labour Cabinet agreed that it was essential to maintain the Gold Standard and that the Budget needed to be balanced, but divided seriously over some of the measures proposed. Henderson found himself at the head of a minority of nearly half the Cabinet who could not accept a cut in unemployment benefit. With the Cabinet so clearly divided it decided to resign office. On 24 August 1931 it was announced that MacDonald was forming an emergency National Government with members of all parties in order to tackle the crisis. However the Labour Party repudiated this government, and the National Executive expelled from the party MacDonald and all other Labour members who supported him (Henderson cast the only vote against this). Henderson now became leader of the party as it became ever more hostile to the Government. With the economic and political situation still uncertain, the National Government decided to call a general election, and in the largest landslide in British political history, it won an overwhelming majority. Labour was reduced to just 46 MPs, and yet again Henderson lost his seat. The following year he relinquished the party leadership.

Henderson returned to Parliament after winning a by-election (Clay Cross). Uniquely, he was elected to Parliament a total of five times at by-elections where he was not the previous MP, and he holds the record for the greatest number of comebacks from losing his seat.

He spent the rest of his life trying to halt the gathering storm of war. He worked with the World League of Peace and chaired the Geneva Disarmament Conference. In 1934 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Arthur Henderson died aged 72 in 1935. Two of his sons also became Labour politicians. His second son William was created Baron Henderson in 1945 while his third son Arthur was made Baron Rowley in 1966.