<Back to Index>

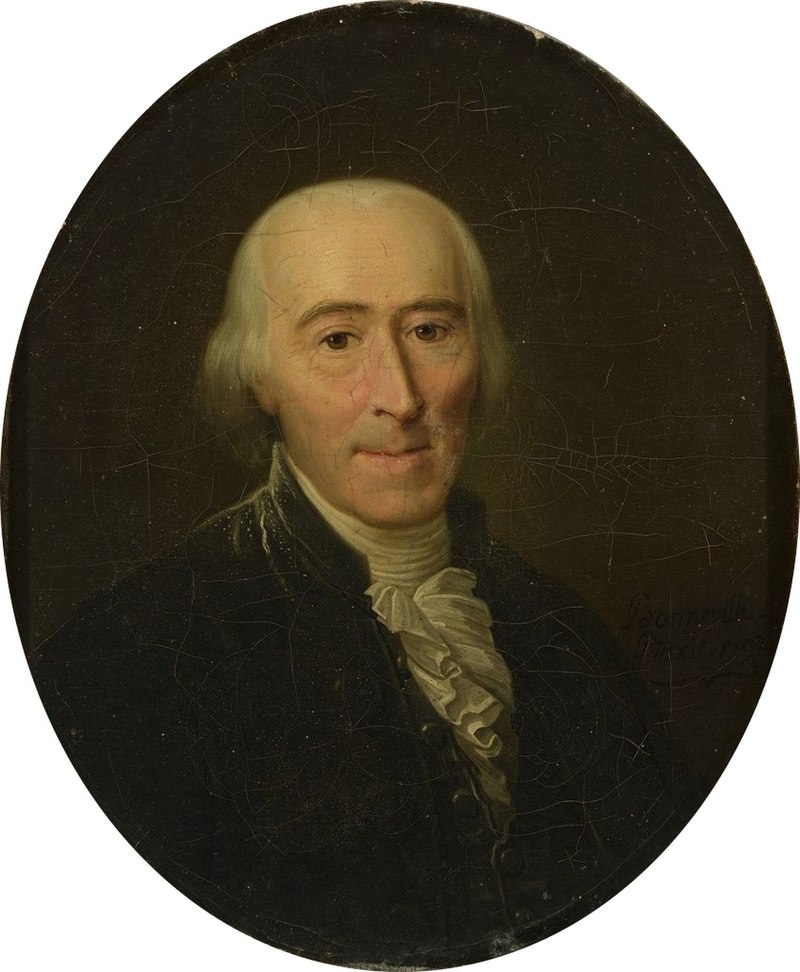

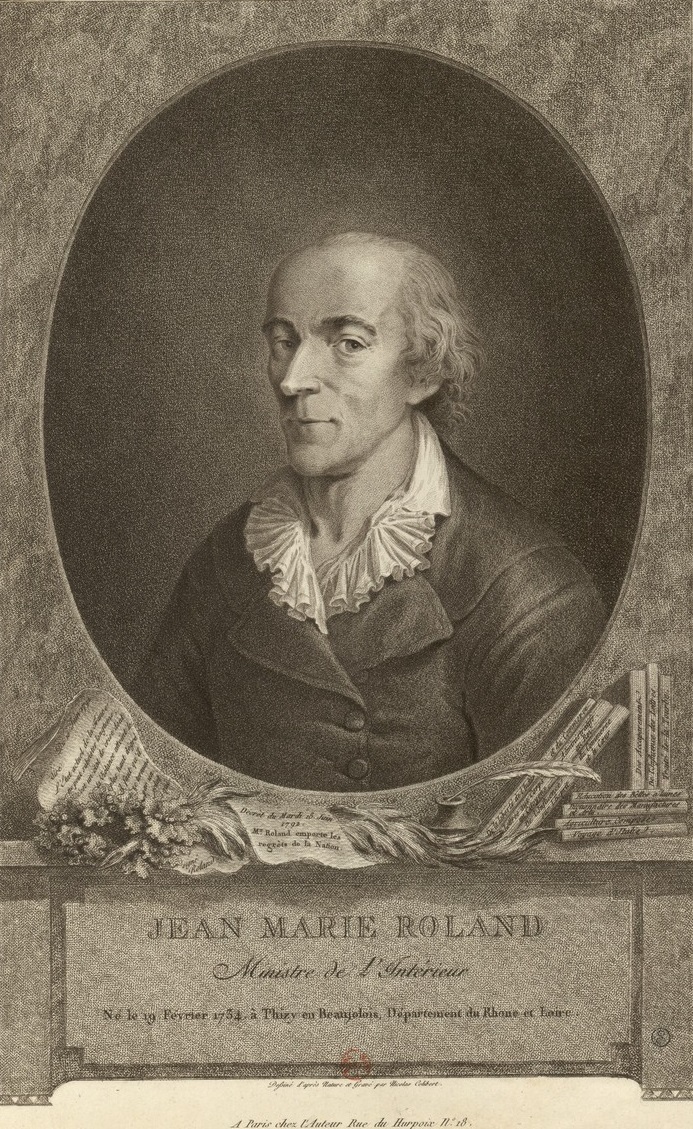

- Minister of the Interior, Minister of Justice and Economist Jean - Marie Roland, vicomte de la Platière, 1734

- Political Activist Marie - Jeanne "Manon" Philipon Roland, 1754

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean-Marie Roland, de la Platière (18 February 1734 - 10 November 1793) was a French manufacturer in Lyon and became the leader of the Girondist faction in the French Revolution, largely influenced in this direction by his wife, Marie - Jeanne "Manon" Roland de la Platiere. He served as a minister of the interior in King Louis XVI's government in 1792.

Roland de la Platière was born and baptized on February 18, 1734 in Thizy, Rhône. He was a studious child, who received a thorough education. At the age of 18 years old, Roland was offered the choice of becoming either a businessman or a priest. But he declined both offers and took up studying manufacturing, leading him to the city of Lyons. Two years later, a cousin and inspector of manufactures offered Roland a position in Rouen. He gladly accepted the job. Roland then was transferred to Languedoc, where he became an enthusiastic economist but soon became ill from overwork. He was then offered the less stressful job of lead inspector of Picardy which was the third most important manufacturing province in France in 1781.

Later that year he married Marie - Jeanne Phlipon, better

known simply as Madame Roland, the daughter of a Parisian

engraver. Madame Roland was just as involved in Jean -

Marie's work as he was, editing much of his writing and

supporting his political goals. For the first four years

of their marriage, Roland continued to live in Picardy and

work as a factory inspector. His knowledge of commercial

affairs enabled him to contribute articles to the Encyclopédie

Méthodique, a three volume encyclopedia of

manufacturing and industry, in which, as in all his

literary work, he was assisted by his wife.

During the first year of the Revolution, the Rolands moved to Lyon, where their influence grew and their political ambitions became clear. From the beginning of the Revolution, they affiliated with the liberal cause. The articles they contributed to the Courrier de Lyon came to the attention of the Parisian press; although Roland signed them, it was Madame Roland who wrote them. The city then sent Roland to Paris to inform the Constituent Assembly of the critical state of the silk industry and to ask for relief of Lyon's debt. As a result, a correspondence began between Roland, Jacques Pierre Brissot and other supporters of the Revolution, whom he had met in Paris. The Rolands arrived in Paris during February 1791, and remained there until September. They frequented the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, entertaining deputies who later became leading Girondists, and taking an active part in the political landscape. Meanwhile Madame Roland opened her first salon, helping her husband's name become better known in the capital.

In September 1791, Roland's mission was complete and he returned to Lyon. By then, however, inspectorships of manufacture had been abolished, so the Roland family decided to move and make their new home in Paris. Roland became a member of the Jacobin Club, and their influence continued to grow. Madame Roland's salon becoming the rendezvous of Brissot, Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve, Maximilien Robespierre and other leaders of the popular movement - especially François Nicolas Leonard Buzot.

When the Girondins assumed power, Roland found himself appointed minister of the interior on 23 March 1792, displaying both his administrative ability and what the Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh Edition, 1911) characterized as "a bourgeois brusqueness". His wife's influence on his declarations of policy was particularly strong in this period: as Roland was ex officio excluded from the Legislative Assembly, these declarations were in writing, and so most prone to exhibit Madame Roland's personal beliefs.

King Louis XVI used his veto power to prevent decrees against émigrés and the non-juring clergy. Madame Roland therefore wrote a letter addressing the royal refusal to sanction the decrees and the role of the king in the state, which her husband addressed and sent to the king. When it remained unanswered, Roland read it aloud in full council and in the king's presence. Judged inconsistent with a minister's position and disrespectful in tone, the incident led to Roland's dismissal. However, he then read the letter to the Assembly, which ordered it printed and circulated. It became a manifesto of dissatisfaction, and the Assembly's subsequent demand that Roland and other dismissed ministers be reinstated eventually led to the king's dethronement.

After the insurrection of 10 August, Roland was reinstated as Interior Minister, but was dismayed by what he saw as the lack of progress made by the Revolution. As a provincial, he opposed the Montagnards who aimed at supremacy not only in Paris but in the government as well. His hostility to the Paris Commune prompted him to propose transferring the government to Blois; and his attacks on Robespierre and his associates made him very unpopular. After failing to seal the armoire de fer (iron chest) found in the Tuileries Palace, containing documents that indicated Louis XVI's relations with corrupt politicians, he was accused of destroying some of the evidence within. Finally, during the trial of the king, he and the Girondists demanded that the sentence should be decided by a poll of the French people rather than the National Convention. Two days after the king's execution, he resigned his office.

Not long after he resigned as minister, the Girondins

came under attack and Roland was denounced as well. Roland

fled Paris and went into hiding; in his absence, he was

sentenced to death. Madame Roland remained in Paris and

was arrested and executed. When Roland learned of his

wife's death, he wandered away from his refuge in Rouen

and wrote a few words expressing his horror at the Reign

of Terror: "From the moment when I learned that they had

murdered my wife, I would no longer remain in a world

stained with enemies." He attached the paper to his chest,

sat up against a tree, and ran a cane - sword through his

heart.

Marie-Jeanne Phlipon Roland, better known simply as Madame Roland and born Marie - Jeanne Phlipon (17 March 1754 - 8 November 1793), was, together with her husband Jean - Marie Roland de la Platière, a supporter of the French Revolution and influential member of the Girondist faction. She fell out of favor during the Reign of Terror and died on the guillotine.

Madame Roland, born Marie - Jeanne Phlipon, the sole surviving child of eight pregnancies, was born to Gratien Phlipon and Madame Phlipon in March 1754. From her early years she was a successful, enthusiastic, and talented student. In her youth she studied literature, music and drawing. From the beginning she was strong willed and frequently challenged her father and instructors as she progressed through an advanced, well-rounded education.

Enthusiastically supporting her education, Jeanne's parents enrolled her in the convent school of the Sisterhood of the Congregation in Paris - for one year only. She was enthusiastically religious, leading John Abbott to state "God thus became in Jane's mind a vision of poetic beauty." Following her convent school education, she pursued her education independently, Abbott relating that "Heraldry and books of romance, lives of the saints and fairy legends, biography, travels, history, political philosophy, poetry and treatises upon morals, were all read and meditated upon by this young child." Several Multiple literary figures influenced Roland's philosophy, including Voltaire, Montesquieu, Plutarch and others. Most significantly, Rousseau's literature strongly influenced Roland's understanding of feminine virtue and political philosophy, and she came to understand a woman's genius as residing in "a pleasurable loss of self - control."

Manon Phlipon (as her close friends and relatives called

her) also, as she traveled, developed an increasing

awareness of the outside world. In 1774, on a trip to Versailles, some of her most

famous letters were sent to her friend Sophie, wherein she

first begins to display an interest in politics,

describing the perfect government as one which contained

"enlightened and well meaning ministers, a young prince

docile to their council who wants to do good, a lovable

and well doing queen, an easy court, pleasant and decent,

an honorable legislative body, a charming people who wants

nothing but the power to love its master...". Already,

Manon was disregarding the idea of an absolute monarchy by

placing the authority and importance of government

ministers before the crown.

In the winter of 1780, Manon Phlipon married the philosopher Jean - Marie Roland de la Platière. 20 years her senior, M. Roland was politically ambitious, and following their marriage, Madame Roland's love for literature and her husband's political aspirations formed a new foundation for her intellectual development. She collaborated on a number of M. Roland's works: the Dictionnaire des Manufactures, Arts et Métiers, and a contribution to Panchoucke's Encyclopedie Methodique, in particular. Her most significant influence flowed through her husband's political writings. Nevertheless, attempting to conform to Rousseau's model of femininity, she also carefully restricted herself "well within the limits of a woman's domestic function." Thus, with him and through him, she proved both powerful and influential in the era of the French Revolution.

In 1784, she obtained a promotion for her husband which transferred him to Lyon, where she began building her network of friends and associates. In Lyon, the Rolands began to express their political support for the revolution through letters to the journal Patriote Français. Their voice was noticed and in November 1790, Jean - Marie was elected to represent Lyon in Paris, negotiating a loan to reduce the debt of Lyon. When the couple moved from Lyon to Paris in 1791, she began to take an even more active role. Her salon at the Hotel Britannique in Paris became the rendezvous of Brissot, Pétion, Robespierre and other leaders of the popular movement. An especially esteemed guest was Buzot, whom she loved with platonic enthusiasm. These leaders of the Girondist faction of the Jacobin Club met to discuss the rights of citizens and strategies to transform the French from subjects of the Monarchy into citizens of a constitutional republic.

In person, Madame Roland is said to have been attractive but not beautiful; her ideas were clear and far reaching, her manner calm, and her power of observation extremely acute. Madame Roland’s ability to weave social networks fed the Rolands' growing popularity; an invitation from Madame Roland would signify acknowledged importance to the developing French government. It was through Manon that one gained access to the inner circle of the growing Gironde. Inevitably, her activity placed her in the center of political aspirations where she swayed a company of the most talented men of progress.

As noted above, Madame Roland began her movement toward political involvement slowly, initially acting as her husband’s secretary, and later developing into a far more influential member of revolutionary politics. As time went on she realized that she could tweak a number of her husband’s letters and still sign them in his name. M. Roland’s rise in politics and the Girondin faction subsequently improved Madame Roland’s influence. In maintenance of her feminist beliefs she never spoke during formal meetings. Instead she listened intently at her desk, taking notes, thus educating herself on political matters. Independently, M. Roland performed sufficiently in his duties as a minister, possessing reasonable knowledge, activity, and integrity. In combination with Madame Roland, he shone due to his ability to articulate writings infused with spirit, gentleness, authoritative reason, and seducing sentiment. Consequently, whenever M. Roland spoke, it was generally known that he was speaking also for her. Girondin policies reflected her sentiments. This political influence continued until the downfall of the Girondin movement, related to Madame Roland's notoriety provoking strong opposition from the Montagnards and celebrated figures such as Robespierre, Danton and Marat.

As a result of ideological differences, Madame Roland and her husband defected from the Jacobins in early 1792 and, with Jacques - Pierre Brissot, formed the moderate Girondin party. The Girondists desire to bring liberty to the people, whilst simultaneously implementing control coincided with Madame Roland’s political beliefs, thus satisfying her ‘appetite’: “All her tastes were with the ancient nobility and their defenders. All her principles were with the people.” Succeeding the surrender of King Louis XVI, the Girondists installed M. Roland as Minister of the Interior. At the time, this position was particularly dangerous, creating an alternate representation of the French monarchy. This 'promotion' added to the spirit of Madame Roland, “whose all - absorbing passion it now was to elevate her husband to the highest summits of greatness, was gratified in view of the honor and agitated in view of the peril.” During this period, she authored much of his official correspondence, including the letter to the King of June 21, 1792, which urged the King to publicly pledge his loyalty and cooperation to the new republic, or suffer the consequences of escalating civil unrest. Madame Roland’s sharply worded passion cost her husband his ministry, but satisfied Madame Roland’s pride and passion. This letter to the King could be considered the peak of her political influence. After Monsieur Roland made a stand against the worst excesses of the Revolution, however, the couple became unpopular. Once, Madame Roland appeared personally in the Assembly to repel the falsehoods of an accuser, and her ease and dignity evoked enthusiasm and compelled acquittal. Her drive, focus, and radiant intelligence made her the equal in accomplishments of any contemporary male politician.

Nevertheless, the accusations mounted. On the morning of

1 June 1793, she, along with other Girondins, was arrested

for treason and, as a woman who had betrayed her gender,

for her political activism. She was thrown into the prison

of the Abbaye. Her husband escaped to Rouen with her help.

Released for an hour from the Abbaye, she was again

arrested and placed in Sainte -

Pelagie, and finally transferred to the

Conciergerie. In prison, she was respected by the guards,

and was allowed the privilege of writing materials and

occasional visits from devoted friends. There, she wrote

her Appel à l'impartiale postérité, memoirs which

display a strange alternation between self praise and love

of country, the trivial and the sublime. She was tried on

trumped up charges of harboring royalist sympathies, but

it was plain that her death was part of Robespierre's

purge of the Girondist opposition.

Perhaps some of the most interesting days of Madame Roland’s life took place in prison as she struggled with her concept of a woman’s place in the nation of France after having been forced to lurk in the shadows to gain her own influence over the nation. Though she had earlier stated that she would "rather chew off (her own) fingers than become a writer," Madame Roland began writing her memoirs during her stay in prison. Madame Roland wrote her memoirs in five months, with sections smuggled from the prison by her frequent guests. In her memoirs, she reflected upon her studies, passions and political events. Madame Roland climbed the political scale by editing and modifying her husband’s platform but she established her historical significance through her recorded memoirs. Manon proved that women could significantly affect national politics. She proved women to be valuable active partners to political success. After Madame Roland helped her husband escape Paris, she accepted her fate of death on the guillotine as the only way to clear her name and reputation. Refusing to compromise her principles and remaining true to the ideals of Rousseau, Voltaire and Plutarch, she died as a citizen of the republic, not a subject of the monarchy. After the revolution, her memoirs were published in 1795, so that Madame Roland continued to influence the formation of the French republic.

On 8 November 1793, she was conveyed to the guillotine. Before placing her head on the block, she bowed before the clay statue of Liberty in the Place de la Révolution, uttering the famous remark for which she is remembered:

O Liberté, que de crimes on commet en ton nom! (Oh Liberty, what crimes are committed in thy name!)

Her corpse was disposed of in the Madeleine Cemetery. Two days after her execution, her husband, Jean - Marie Roland, committed suicide on a country lane outside Rouen.