<Back to Index>

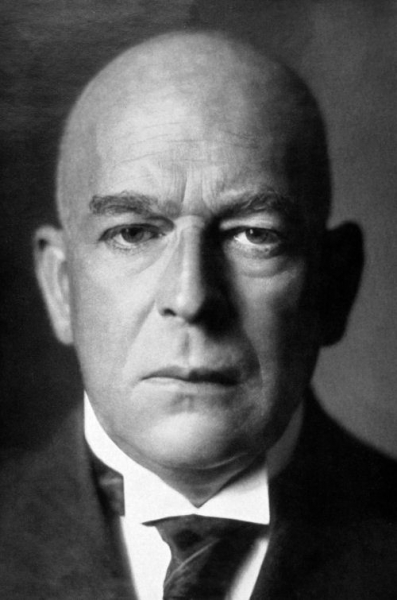

- Historian and

Philosopher Oswald

Manuel Arnold Gottfried Spengler, 1880

PAGE SPONSOR

Oswald Manuel Arnold Gottfried Spengler (29 May 1880 - 8 May 1936) was a German historian and philosopher whose interests also included mathematics, science, and art. He is best known for his book The Decline of the West (Der Untergang des Abendlandes), published in 1918 and 1922, where he proposed a new theory, according to which the lifespan of civilizations is limited and ultimately they decay. In 1920 Spengler produced Prussiandom and Socialism (Preußentum und Sozialismus), which argued for an organic, nationalist version of socialism and authoritarianism. He wrote extensively throughout World War I and the interwar period, and supported German hegemony in Europe. Some National Socialists (such as Goebbels) held Spengler as an intellectual precursor but he was ostracized after 1933 for his pessimism about Germany's and Europe's future, his refusal to support Nazi ideas of racial superiority, and his critical work The Hour of Decision.

Oswald Spengler was born in 1880 in Blankenburg (then in the Duchy of Brunswick, German Empire) at the foot of the Harz mountains, the eldest of four children, and the only boy. His family was conservative German of the petite bourgeoisie. His father, originally a mining technician, who came from a long line of mine workers, was a post office bureaucrat. His childhood home was emotionally reserved, and the young Spengler turned to books and the great cultural personalities for succor. He had imperfect health, and suffered throughout his life from migraine headaches and from an anxiety complex.

At the age of ten, his family moved to the university city of Halle. Here Spengler received a classical education at the local Gymnasium (academically oriented secondary school), studying Greek, Latin, mathematics and natural sciences. Here, too, he developed his affinity for the arts — especially poetry, drama and music — and came under the influence of the ideas of Goethe and Nietzsche. He even experimented with a few artistic creations, some of which still survive.

After his father's death in 1901 Spengler attended several universities (Munich, Berlin and Halle) as a private scholar, taking courses in a wide range of subjects: history, philosophy, mathematics, natural science, literature, the classics, music and fine arts. His private studies were undirected. In 1903, he failed his doctoral thesis on Heraclitus because of insufficient references, which effectively ended his chances of an academic career. In 1904 he received his Ph.D., and in 1905 suffered a nervous breakdown.

Scholars remark that his life seemed rather uneventful. He briefly served as a teacher in Saarbrücken and then in Düsseldorf. From 1908 to 1911 he worked at a grammar school (Realgymnasium) in Hamburg, where he taught science, German history and mathematics.

In 1911, following his mother's death, he moved to Munich, where he would live until his death in 1936. He lived as a cloistered scholar, supported by his modest inheritance. Spengler survived on very limited means and was marked by loneliness. He owned no books, and took jobs as a tutor or wrote for magazines to earn additional income.

He began work on the first volume of Decline of the West intending at first to focus on Germany within Europe, but the Agadir Crisis affected him deeply, and he widened the scope of his study. Spengler was inspired by Otto Seeck's work The Decline of Antiquity in naming his own effort. The book was completed in 1914, but publishing was delayed by World War I. Due to a congenital heart problem, he was not called up for military service. During the war, however, his inheritance was largely useless because it was invested overseas; thus Spengler lived in genuine poverty for this period.

When Decline came out in the summer of 1918 it became a wild success. The perceived national humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and later the economic depression around 1923 fueled by hyperinflation seemed to prove Spengler right. It comforted Germans because it seemingly rationalized their downfall as part of larger world - historical processes. The book met with wide success outside of Germany as well, and by 1919 had been translated into several other languages. Spengler rejected a subsequent offer to become Professor of Philosophy at the University of Göttingen, saying he needed time to focus on writing.

The book was widely discussed, even by those who had not read it. Historians took umbrage at an amateur effort by an untrained author and his unapologetically non scientific approach. Thomas Mann compared reading Spengler's book to reading Schopenhauer for the first time. Academics gave it a mixed reception. Max Weber described Spengler as a "very ingenious and learned dilettante", while Karl Popper described the thesis as "pointless". The great historian of antiquity Eduard Meyer thought highly of Spengler, although he also had some criticisms of him. Spengler's obscurity, intuitionalism, and mysticism were easy targets, especially for the Positivists and neo - Kantians who saw no meaning in history. The critic and æsthete Count Harry Kessler thought him unoriginal and rather inane, especially in regard to his opinion on Nietzsche. Ludwig Wittgenstein, however, shared Spengler's cultural pessimism. Spengler's work became an important foundation for the social cycle theory.

His book was a smashing success among intellectuals worldwide as it predicted the disintegration of European and American civilization after a violent "age of Caesarism," arguing by detailed analogies with other civilizations. It deepened the post World War I pessimism in Europe. German Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer explained that at the end of the First World War, Spengler's very title was enough to inflame imaginations: "At this time many, if not most of us, had realized that something was rotten in the state of our highly prized Western civilization. Spengler's book expressed in a sharp and trenchant way this general uneasiness." Northrop Frye argued that while every element of Spengler's thesis has been refuted a dozen times, it is "one of the world's great Romantic poems" and its leading ideas are "as much part of our mental outlook today as the electron or the dinosaur, and in that sense we are all Spenglerians."

Spengler's pessimistic predictions about the inevitable decline of the West inspired Third World intellectuals, ranging from China and Korea to Chile, eager to identify the fall of western imperialism. In Britain and America, however, Spengler's pessimism was later countered by the optimism of Arnold J. Toynbee in London, who wrote world history in the 1940s with a greater stress on religion.

A 1928 Time review of the second volume of Decline described the immense influence and controversy Spengler's ideas enjoyed during the 1920s: "When the first volume of The Decline of the West appeared in Germany a few years ago, thousands of copies were sold. Cultivated European discourse quickly became Spengler - saturated. Spenglerism spurted from the pens of countless disciples. It was imperative to read Spengler, to sympathize or revolt. It still remains so."

In the second volume, published in 1922, Spengler argued that German socialism differed from Marxism, and was in fact compatible with traditional German conservatism. In 1924, following the social - economic upheaval and inflation, Spengler entered politics in an effort to bring Reichswehr general Hans von Seeckt to power as the country's leader. The attempt failed and Spengler proved ineffective in practical politics. In 1931, he published Man and Technics, which warned against the dangers of technology and industrialism to culture. He especially pointed to the tendency of Western technology to spread to hostile "Colored races" which would then use the weapons against the West. It was poorly received because of its anti - industrialism. This book contains the well known Spengler quote "Optimism is cowardice".

Despite voting for Hitler over Hindenburg in 1932, Spengler found the Führer vulgar. He met Hitler in 1933 and after a lengthy discussion remained unimpressed, saying that Germany did not need a "heroic tenor (Heldentenor: one of several conventional tenor classifications) but a real hero (Held)." He publicly quarreled with Alfred Rosenberg, and his pessimism and remarks about the Führer resulted in isolation and public silence. He further rejected offers from Joseph Goebbels to give public speeches. However, Spengler did become a member of the German Academy in the course of the year.

The Hour of Decision, published in 1934, was a bestseller, but the Nazis later banned it for its critiques of National Socialism. Spengler's criticisms of liberalism were welcomed by the Nazis, but Spengler disagreed with their biological ideology and anti - Semitism. While racial mysticism played a key role in his own worldview, Spengler had always been an outspoken critic of the pseudo - scientific racial theories professed by the Nazis and many others in his time, and was not inclined to change his views upon Hitler's rise to power. Although himself a German nationalist, Spengler viewed the Nazis as too narrowly German, and not occidental enough to lead the fight against other peoples. The book also warned of a coming world war in which Western Civilization risked being destroyed, and was widely distributed abroad before eventually being banned in Germany. A Time review of The Hour of Decision noted his international popularity as a polemicist, observing that "When Oswald Spengler speaks, many a Western Worldling stops to listen". The review recommended the book for "readers who enjoy vigorous writing", who "will be glad to be rubbed the wrong way by Spengler's harsh aphorisms" and his pessimistic predictions.

In his private papers, Spengler denounced Nazi anti - Semitism in even stronger terms, writing "and how much envy of the capability of other people in view of one's lack of it lies hidden in anti - Semitism!" and that "when one would rather destroy business and scholarship than see Jews in them, one is an ideologue, i.e., a danger for the nation. Idiotic."

Spengler spent his final years in Munich, listening to Beethoven, reading Molière and Shakespeare, buying several thousand books, and collecting ancient Turkish, Persian and Hindu weapons. He made occasional trips to the Harz mountains, and to Italy. Shortly before his death, in a letter to a friend, he remarked that "the German Reich in ten years will probably no longer exist". He died of a heart attack on May 8, 1936 in Munich, three weeks before his 56th birthday and exactly nine years before the fall of the Third Reich.