<Back to Index>

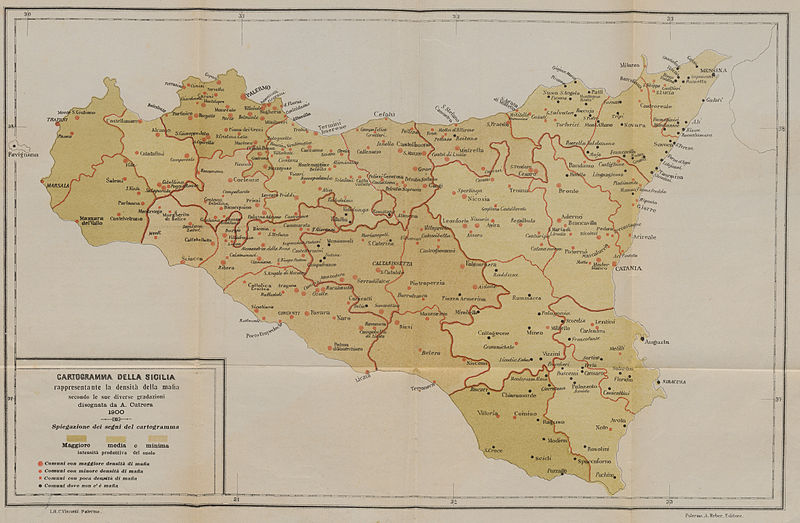

- Family of Sicily Mafia (Cosa Nostra), 1800s

PAGE SPONSOR

The Mafia (also known as Cosa Nostra) is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share a common organizational structure and code of conduct, and whose common enterprise is protection racketeering. Each group, known as a "family", "clan" or "cosca", claims sovereignty over a territory in which it operates its rackets – usually a town or village or a neighborhood (borgata) of a larger city. Its members call themselves "men of honor", although the public often refers to them as "mafiosi".

According to the classic definition, the Mafia is a criminal organization originating in Sicily. However, the term "mafia" has become a generic term for any organized criminal network with similar structure, methods and interests.

The Mafia proper frequently parallels, collaborates with or clashes with, networks originating in other parts of southern Italy, such as the Camorra (from Campania), the 'Ndrangheta (from Calabria), the Stidda (southern Sicily) and the Sacra Corona Unita (from Apulia). However, Giovanni Falcone, the anti - Mafia judge murdered by the Mafia in 1992, objected to the conflation of the term "Mafia" with organized crime in general:

While there was a time when people were reluctant to pronounce the word 'Mafia' ... nowadays people have gone so far in the opposite direction that it has become an overused term ... I am no longer willing to accept the habit of speaking of the Mafia in descriptive and all - inclusive terms that make it possible to stack up phenomena that are indeed related to the field of organized crime but that have little or nothing in common with the Mafia.—Giovanni Falcone, 1990

The American Mafia arose from offshoots of the Mafia that emerged in the United States during the late nineteenth century, following waves of emigration from Sicily. There were similar offshoots in Canada among Italian Canadians. However, while the same has been claimed of organized crime in Australia, this appears to result from confusion with 'Ndrangheta, which is generally regarded as more prominent among Italian Australians.

There are several theories about the origin of the term "Mafia" (sometimes spelled "Maffia" in early texts). The Sicilian adjective mafiusu (in Italian: mafioso) may derive from the slang Arabic mahyas (مهياص), meaning "aggressive boasting, bragging", or marfud (مرفوض) meaning "rejected". Roughly translated, it means "swagger," but can also be translated as "boldness, bravado". In reference to a man, mafiusu in 19th century Sicily was ambiguous, signifying a bully, arrogant but also fearless, enterprising and proud, according to scholar Diego Gambetta. In reference to a woman, however, the feminine form adjective "mafiusa" means beautiful and attractive.

Other possible origins from Arabic:

- maha = quarry, cave;

- mu'afa = safety, protection.

The public's association of the word with the criminal secret society was perhaps inspired by the 1863 play "I mafiusi di la Vicaria" ("The Mafiosi of the Vicaria") by Giuseppe Rizzotto and Gaetano Mosca. The words Mafia and mafiusi are never mentioned in the play; they were probably put in the title to add a local flair. The play is about a Palermo prison gang with traits similar to the Mafia: a boss, an initiation ritual, and talk of "umirtà" (omertà or code of silence) and "pizzu" (a code word for extortion money). The play had great success throughout Italy. Soon after, the use of the term "mafia" began appearing in the Italian state's early reports on the phenomenon. The word made its first official appearance in 1865 in a report by the prefect of Palermo, Filippo Antonio Gualterio.

According to legend, the word Mafia was first used in the

Sicilian revolt – the Sicilian Vespers – against rule of

the Capetian House of Anjou on 30 March 1282. In this

legend, Mafia is the acronym for "Morte Alla

Francia, Italia Avanti" (Italian

for "Death to France, Italy Forward!").

However, this version is now discarded by most serious

historians.

According to Mafia turncoats (pentiti), the real name of the Mafia is "Cosa Nostra" ("Our thing"). When the American mafioso Joseph Valachi testified before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the U.S. Senate Committee on Government Operations in 1963 (known as the Valachi hearings), he revealed that American mafiosi referred to their organization by the term cosa nostra ("our thing" or "this thing of ours"). At the time, it was understood as a proper name, fostered by the FBI and disseminated by the media. The designation gained wide popularity and almost replaced the term Mafia. The FBI even added the article La to the term, calling it La Cosa Nostra (in Italy, the article la is not used when referring to Cosa Nostra).

Italian investigators initially did not take the term seriously, believing it was used only by the American Mafia. In 1984, the Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta revealed to the anti - mafia magistrate Giovanni Falcone that the term was used by the Sicilian Mafia as well. Buscetta dismissed the word "mafia" as a mere literary creation. Other defectors, such as Antonino Calderone and Salvatore Contorno, confirmed the use of Cosa Nostra to describe the Mafia. Mafiosi introduce known members to each other as belonging to cosa nostra ("our thing") or la stessa cosa ("the same thing"), meaning "he is the same thing, a mafioso, as you".

The Sicilian Mafia has used other names to describe itself throughout its history, such as "The Honored Society". Mafiosi are known among themselves as "men of honor" or "men of respect". The Mafia was also known by another term, La Mano Nera ~ the Black Hand. Mafia crimes were often sealed by a black handprint at the scene.

Cosa Nostra should not be confused with other mafia type organizations in Italy such as the 'Ndrangheta in Calabria, the Camorra in Campania, or the Sacra Corona Unita in Apulia.

The genesis of Cosa Nostra is hard to trace

because mafiosi are very secretive and do not keep

historical records of their own. In fact, they have been

known to spread deliberate lies about their past, and

sometimes come to believe in their own myths.

Modern scholars believe that its seeds were planted

in the upheaval of Sicily's transition out of feudalism in

1812 and its later annexation by mainland Italy in 1860.

Under feudalism, the nobility owned most of the land and

enforced law and order through their private armies. After

1812, the feudal barons steadily sold off or rented their

lands to private citizens. Primogeniture was abolished,

land could no longer be seized to settle debts, and one

fifth of the land was to become private property of the

peasants.

The oldest reference to Mafia groups in Sicily dates back

to 1838, in a report of the General Prosecutor of the

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, although the term "mafia" was

not used. The report described the phenomenon rather than

the name: "In many villages, there are unions or

fraternities – kinds of sects – which are called partiti,

with no political color or goal, with no meeting places,

and with no other bond but that of dependency on a chief."

After Italy annexed Sicily in 1860, it redistributed a large share of public and church land to private citizens. The result was a huge boom in landowners: from 2,000 in 1812 to 20,000 by 1861. The nobles also released their private armies to let the state take over the task of law enforcement. However, the authorities were incapable of properly enforcing property rights and contracts, largely due to their inexperience with free market capitalism. Lack of manpower was also a problem: there were often less than 350 active policemen for the entire island. Some towns did not have any permanent police force, only visited every few months by some troops to collect malcontents, leaving criminals to operate with impunity from the law in the interim. With more property owners came more disputes that needed settling, contracts that needed enforcing, and properties that needed protecting. Because the authorities were undermanned and unreliable, property owners turned to extralegal arbitrators and protectors. These extralegal protectors would eventually organize themselves into the first Mafia clans.

Banditry was a serious problem at the time. Rising food prices, the loss of public and church lands, and the loss of feudal common rights pushed many desperate peasants to banditry. With no police to call upon, local elites in countryside towns recruited young men into "companies - at - arms" to hunt down thieves and negotiate the return of stolen property, in exchange for a pardon for the thieves and a fee from the victims. These companies - at - arms were often made up of former bandits and criminals, usually the most skilled and violent of them. Whilst this saved communities the trouble of training their own policemen, this may have made the companies - at - arms more inclined to collude with their former brethren rather than destroy them.

There was little Mafia activity in the eastern half of Sicily. In the east, the ruling elites were more cohesive and active during the transition from feudalism to capitalism. They maintained their large stables of enforcers, and were able to absorb or suppress any emerging violent groups. Furthermore, the land in the east was generally divided into a smaller number of large estates, so there were fewer landowners and their large estates often required full time patrolling. This meant that guardians of such estates tended to be bound to a single employer, giving them little autonomy or leverage to demand high payments. This did not mean there was little violence - the most violent conflicts over land took place in the east, but they did not involve mafiosi.

Mafia activity was most prevalent in the most prosperous areas of western Sicily, especially Palermo, where the dense concentrations of landowners and merchants offered ample opportunities for protection racketeering and extortion. There, a protector could serve multiple clients, giving him greater independence. The greater number of clients demanding protection also allowed him to charge high prices. The landowners in this region were also frequently absent and could not watch over their properties should the mafioso withdraw protection, further increasing his bargaining power.

The lucrative citrus orchards around Palermo were a favorite target of extortionists and protection racketeers, as they had a fragile production system that made them quite vulnerable to sabotage. Mafia clans forced landowners to hire their members as custodians by scaring away unaffiliated applicants. Cattle ranchers were also very vulnerable to thieves, and so they too needed mafioso protection.

In 1864, Niccolò Turrisi Colonna, leader of the Palermo

National Guard, wrote of a "sect of thieves" that operated

across Sicily. This "sect" was mostly rural, composed of

cattle thieves, smugglers, wealthy farmers and their

guards. The sect made "affiliates every day of the

brightest young people coming from the rural class, of the

guardians of the fields in the Palermitan countryside, and

of the large number of smugglers; a sect which gives and

receives protection to and from certain men who make a

living on traffic and internal commerce. It is a sect with

little or no fear of public bodies, because its members

believe that they can easily elude this."

It had special signals to recognize each other, offered

protection services, scorned the law and had a code of

loyalty and non-interaction with the police known as umirtà

("humility"). Colonna warned in his report that the

Italian government's brutal and clumsy attempts to crush

unlawfulness only made the problem worse by alienating the

populace. An 1865 dispatch from the prefect of Palermo to

Rome first officially described the phenomenon as a

"Mafia". An 1876 police report makes the earliest known

description of the familiar initiation ritual.

Mafiosi meddled in politics early on, bullying voters into voting for candidates they favored. At this period in history, only a small fraction of the Sicilian population could vote, so a single mafia boss could control a sizeable chunk of the electorate and thus wield considerable political leverage. Mafiosi used their allies in government to avoid prosecution as well as persecute less well connected rivals. The highly fragmented and shaky Italian political system allowed cliques of Mafia friendly politicians to exert a lot of influence.

In a series of reports between 1898 and 1900, Ermanno Sangiorgi, the police chief

of Palermo, identified 670 mafiosi belonging to eight

Mafia clans that went through alternating phases of

cooperation and conflict.

The report mentioned initiation rituals and codes of

conduct, as well as criminal activities that included

counterfeiting, ransom kidnappings, robbery, murder and

witness intimidation. The Mafia also maintained funds to

support the families of imprisoned members and pay defense

lawyers.

In 1925, Benito Mussolini initiated a campaign to destroy the Mafia and assert Fascist control over Sicilian life. The Mafia threatened and undermined his power in Sicily, and a successful campaign would strengthen him as the new leader, legitimizing and empowering his rule. Not only would this be a great propaganda coup for Fascism, but it would also provide an excuse to suppress his political opponents on the island, since many Sicilian politicians had Mafia links.

As prime minister, he visited Sicily in May 1924 and passed through Piana dei Greci where he was received by the mayor, Mafia boss Francesco Cuccia. At some point Cuccia expressed surprise at Mussolini’s police escort and whispered in his ear: "You are with me, you are under my protection. What do you need all these cops for?" After Mussolini rejected Cuccia's offer of protection, Cuccia instructed the townsfolk to not attend Mussolini's speech. Mussolini felt humiliated and outraged.

Cuccia’s careless remark has passed into history as the catalyst for Mussolini’s war on the Mafia. When Mussolini firmly established his power in January 1925, he appointed Cesare Mori as the Prefect of Palermo in October 1925 and granted him special powers to fight the Mafia. Mori formed a small army of policemen, carabinieri and militiamen, which went from town to town, rounding up suspects. To force suspects to surrender, they would take their families hostage, sell off their property, or publicly slaughter their livestock. By 1928, over 11,000 suspects were arrested. Confessions were sometimes extracted through beatings and torture. Some mafiosi who had been on the losing end of Mafia feuds voluntarily cooperated with prosecutors, perhaps as a way of obtaining protection and revenge. Charges of Mafia association were typically leveled at poor peasants and gabellotti (farm leaseholders), but were avoided when dealing with major landowners. Many were tried en masse. More than 1,200 were convicted and imprisoned, and many others were internally exiled without trial.

Mori's campaign ended in June 1929 when Mussolini recalled him to Rome. Although he did not permanently crush the Mafia as the Fascist press proclaimed, his campaign was nonetheless very successful at suppressing it. As the Mafia informant Antonino Calderone reminisced: "The music changed. Mafiosi had a hard life. [...] After the war the mafia hardly existed anymore. The Sicilian Families had all been broken up."

Sicily's murder rate sharply declined.

Landowners were able to raise the legal rents on their

lands; sometimes as much as ten-thousandfold. Many mafiosi

fled to the United States. Among these were Carlo Gambino

and Joseph Bonanno, who would go on to become powerful

Mafia bosses in New York City.

In 1943, nearly half a million Allied troops invaded Sicily. Crime soared in the upheaval and chaos. Many inmates escaped from their prisons, banditry returned and the black market thrived. During the first six months of Allied occupation, party politics in Sicily were banned. Most institutions, with the exception of the police and carabinieri, were destroyed, and the American occupiers had to build a new order from scratch. As Fascist mayors were deposed, the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories (AMGOT) simply appointed replacements. Many turned out to be mafiosi, such as Calogero Vizzini and Giuseppe Genco Russo. They could easily present themselves as political dissidents, and their anti - communist position gave them additional credibility. Mafia bosses reformed their clans, absorbing some of the marauding bandits into their ranks.

The changing economic landscape of Sicily would shift the Mafia's power base from the rural to the urban. The Minister of Agriculture – a communist – pushed for reforms in which peasants were to get larger shares of produce, be allowed to form cooperatives and take over badly used land, and remove the system by which leaseholders (known as "gabelloti") could rent land from landowners for their own short term use. Owners of especially large estates were to be forced to sell off some of their land. The Mafia, which had connections to many landowners, murdered many socialist reformers. The most notorious attack was the Portella della Ginestra massacre, when 11 persons were killed and 33 wounded during May Day celebrations on May 1, 1947. The bloodbath was perpetrated by the bandit Salvatore Giuliano who was possibly backed by local Mafia bosses. In the end, though, they couldn't stop the process, and many landowners chose to sell their land to mafiosi, who offered more money than the government.

In the 1950s, a crackdown in the United States on drug trafficking led to the

imprisonment of many American mafiosi. Furthermore, Cuba,

a major hub for drug smuggling, fell to Fidel Castro. This

prompted the American mafia boss Joseph Bonanno to return

to Sicily in 1957 to franchise out his heroin operations

to the Sicilian clans. Anticipating rivalries for the

lucrative American drug market, he negotiated the

establishment of a Sicilian Mafia Commission to mediate

disputes.

The post war period saw a huge building boom in Palermo. Allied bombing in World War II had left more than 14,000 people homeless, and migrants were pouring in from the countryside, so there was a huge demand for new homes. Much of this construction was subsidized by public money. In 1956, two Mafia connected officials, Vito Ciancimino and Salvatore Lima, took control of Palermo's Office of Public Works. Between 1959 and 1963, about 80% of building permits were given to just five people, none of whom represented major construction firms and were probably Mafia front men. Construction companies unconnected with the Mafia were forced to pay protection money. Many buildings were illegally constructed before the city's planning was finalized. Mafiosi scared off anyone who dared to question the illegal building. The result of this unregulated building was the demolition of many beautiful historic buildings and the erection of apartment blocks, many of which were not up to standard.

Mafia organizations entirely control the building sector in Palermo – the quarries where aggregates are mined, site clearance firms, cement plants, metal depots for the construction industry, wholesalers for sanitary fixtures, and so on.—Giovanni Falcone, 1982

The First Mafia War was the first high profile conflict between Mafia clans in post war Italy (the Sicilian Mafia has a long history of violent rivalries).

In 1962, the mafia boss Cesare Manzella organized a drug shipment to America with the help of two Sicilian clans, the Grecos and the La Barberas. Manzella entrusted another boss, Calcedonio Di Pisa, to handle the heroin. When the shipment arrived in America, however, the American buyers claimed some heroin was missing, and paid Di Pisa a commensurately lower sum. Di Pisa accused the Americans of defrauding him, while the La Barberas accused Di Pisa of embezzling the missing heroin. The Sicilian Mafia Commission sided with Di Pisa, to the open anger of the La Barberas. The La Barberas murdered Di Pisa and Manzella, triggering a war.

Many non-mafiosi were killed in the crossfire. In April

1963, several bystanders were wounded during a shootout in

Palermo. In May, Angelo La Barbera survived a murder

attempt in Milan. In June, six military officers and a

policeman in Ciaculli were killed while trying to dispose

of a car bomb. These incidents provoked national outrage

and a crackdown in which nearly 2,000 arrests were made.

Mafia activity fell as clans disbanded and mafiosi went

into hiding. The Sicilian Mafia Commission was dissolved;

it would not reform until 1969. 117 suspects were put on

trial in 1968, but most were acquitted or received light

sentences. The inactivity plus money lost to legal fees

and so forth reduced most mafiosi to poverty.

The 1950s and 1960s were difficult times for the mafia, but in the 1970s their rackets grew considerably more lucrative, particularly smuggling. The most lucrative racket of the 1970s was cigarette smuggling. Sicilian and Neapolitan crime bosses negotiated a joint monopoly over the smuggling of cigarettes to Naples.

When heroin refineries operated by Corsican gangsters in

Marseilles were shut down

by French authorities, morphine traffickers looked to

Sicily. Starting in 1975, Cosa Nostra set up heroin

refineries across the island.

As well as refining heroin, Cosa Nostra also

sought to control its distribution. Sicilian mafiosi moved

to the United States to personally control distribution

networks there, often at the expense of their U.S.

counterparts. Heroin addiction in Europe and North America

surged, and seizures by police increased dramatically. By

1982, the Sicilian Mafia controlled about 80% of the

heroin trade in the north-eastern United States.

Heroin was often distributed to street dealers from Mafia

owned pizzerias, and the revenues could be passed off as

restaurant profits (the so-called Pizza Connection).

In the early 1970s, Luciano Leggio, boss of the Corleone clan and member of the Sicilian Mafia Commission, forged a coalition of mafia clans known as the Corleonesi, with himself as its leader. He initiated a campaign to dominate Cosa Nostra and its narcotics trade. Because Leggio was imprisoned in 1974, he acted through his deputy, Salvatore Riina, to whom he would eventually hand over control. The Corleonesi bribed cash strapped Palermo clans into the fold, subverted members of other clans and secretly recruited new members. In 1977, the Corleonesi had Gaetano Badalamenti expelled from the Commission on trumped up charges of hiding drug revenues. In April 1981, the Corleonesi murdered another rival member of the Commission, Stefano Bontade, and the Second Mafia War began in earnest. Hundreds of enemy mafiosi and their relatives were murdered, sometimes by traitors in their own clans. By manipulating the Mafia's rules and eliminating rivals, the Corleonesi came to completely dominate the Commission. Riina used his power over the Commission to replace the bosses of certain clans with hand picked regents. In the end, the Corleonesi faction won and Riina effectively became the "boss of bosses" of the Sicilian Mafia.

At the same time the Corleonesi waged their campaign to

dominate Cosa Nostra, they also waged a campaign

of murder against journalists, officials and policemen who

dared cross them. The police were frustrated with the lack

of help they were receiving from witnesses and

politicians. At the funeral of a policeman murdered by

mafiosi in 1985, policemen insulted and spat at two

attending politicians, and a fight broke out between them

and military police.

In the early 1980s, the magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino began a campaign against Cosa Nostra. Their big break came with the arrest of Tommaso Buscetta, a mafioso who chose to turn informant in exchange for protection from the Corleonesi, who had already murdered many of his friends and relatives. Other mafiosi followed his example. Falcone and Borsellino compiled their testimonies and organized the Maxi Trial, which lasted from February 1986 to December 1987. It was held in a fortified courthouse specially built for the occasion. 474 mafiosi were put on trial, of whom 342 were convicted. In January 1992 the Italian Supreme Court confirmed these convictions.

The Mafia retaliated violently. In 1988, they murdered a Palermo judge and his son; three years later a prosecutor and an anti - mafia businessman were also murdered. Salvatore Lima, a close political ally of the Mafia, was murdered for failing to reverse the convictions as promised. Falcone and Borsellino were killed by bombs in 1992. This led to a public outcry and a massive government crackdown, resulting in the arrest of Salvatore Riina in January 1993. More and more defectors emerged. Many would pay a high price for their cooperation, usually through the murder of relatives. For example, Francesco Marino Mannoia's mother, aunt and sister were murdered.

After Riina's arrest, the Mafia began a campaign of terrorism on the Italian mainland. Tourist spots such as the Via dei Georgofili in Florence, Via Palestro in Milan, and the Piazza San Giovanni in Laterano and Via San Teodoro in Rome were attacked, leaving 10 dead and 93 injured and causing severe damage to cultural heritage such as the Uffizi Gallery. When the Catholic Church openly condemned the Mafia, two churches were bombed and an anti - Mafia priest shot dead in Rome.

After Riina's capture, leadership of the Mafia was

briefly held by Leoluca Bagarella, then passed to Bernardo

Provenzano when the former was himself captured in 1995.

Provenzano halted the campaign of violence and replaced it

with a campaign of quietness known as pax mafiosa.

Under Bernardo Provenzano's leadership, murders of state officials were halted. He also halted the policy of murdering informants and their families, with a view instead to getting them to retract their testimonies and return to the fold. He also restored the common support fund for imprisoned mafiosi.

The tide of defectors was greatly stemmed. The Mafia

preferred to initiate relatives of existing mafiosi,

believing them to be less prone to defection. Provenzano

was arrested in 2006, after 43 years on the run.

The incarcerated bosses are currently subjected to harsh controls on their contact with the outside world, limiting their ability to run their operations from behind bars under the article 41-bis prison regime. Antonino Giuffrè – a close confidant of Provenzano, turned pentito shortly after his capture in 2002 – alleges that in 1993 Cosa Nostra had direct contact with representatives of Silvio Berlusconi who was then planning the birth of Forza Italia.

The alleged deal included a repeal of 41 bis, among other anti - Mafia laws in return for electoral support in Sicily. Nevertheless, Giuffrè's declarations have not yet been confirmed. The Italian Parliament, with the full support of Forza Italia reinforced the provisions of the 41 bis, which was to expire in 2002 but has been prolonged for another four years and extended to other crimes such as terrorism. However, according to one of Italy’s leading magazines, L'Espresso, 119 mafiosi – one-fifth of those incarcerated under the 41 bis regime – have been released on an individual basis. The human rights group Amnesty International has expressed concern that the 41-bis regime could in some circumstances amount to "cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment" for prisoners.

In addition to Salvatore Lima, mentioned above, the politician Giulio Andreotti and the High Court judge Corrado Carnevale have long been suspected of having ties to the Mafia.

By the late 1990s, the weakened Cosa Nostra had to yield

most of the illegal drug trade to the 'Ndrangheta crime

organization from Calabria. In 2006, the latter was

estimated to control 80% of the cocaine imported to

Europe.

In 2012, it was reported that Mafia had joined forces with

the Mexican drug cartels.

It is difficult to define exactly, the single function, or goal, of the phenomenon of the Mafia. Until the early 1980s, mafia was generally considered a unique Sicilian cultural attitude and form of power, excluding any corporate or organizational dimension. Some even used it as a defensive attempt to render the Mafia benign and romantic: not a criminal association, but the sum of Sicilian values that outsiders never will understand.

Leopoldo Franchetti, an Italian deputy who traveled to Sicily and who wrote one of the first authoritative reports on the mafia in 1876, saw the Mafia as an "industry of violence" and described the designation of the term "mafia":

the term mafia found a class of violent criminals ready and waiting for a name to define them, and, given their special character and importance in Sicilian society, they had the right to a different name from that defining vulgar criminals in other countries.—Leopoldo Franchetti, 1876

Franchetti saw the Mafia as deeply rooted in Sicilian society and impossible to quench unless the very structure of the island's social institutions were to undergo a fundamental change.

Some observers saw "mafia" as a set of attributes deeply rooted in popular culture, as a "way of being", as illustrated in the definition by the Sicilian ethnographer, Giuseppe Pitrè:

Mafia is the consciousness of one's own worth, the exaggerated concept of individual force as the sole arbiter of every conflict, of every clash of interests or ideas.—Giuseppe Pitrè, 1889

Like Pitrè, many scholars viewed mafiosi as individuals behaving according to specific subcultural codes, but did not consider the Mafia a formal organization. Judicial investigations and scientific research in the 1980s provided solid proof of the existence of well structured Mafia groups with entrepreneurial characteristics. The Mafia was seen as an enterprise and its economic activities became the focus of academic analyses. Ignoring the cultural aspects, the Mafia is often erroneously seen as similar to other non-Sicilian organized criminal associations.

However, these two paradigms missed essential aspects of the Mafia that became clear when investigators were confronted with the testimonies of Mafia turncoats, like those of Buscetta to judge Falcone at the Maxi Trial. The economic approach to explain the Mafia did illustrate the development and operations of the Mafia business, but neglected the cultural symbols and codes by which the Mafia legitimized its existence and by which it rooted itself into Sicilian society.

The economic paradigm was prevalent when the Italian Penal Code definition of criminal conspiracy (Article 416) was extended by Pio La Torre. Article 416 bis defines an association as being of Mafia type nature "when those belonging to the association exploit the potential for intimidation which their membership gives them, and the compliance and omerta which membership entails and which lead to the committing of crimes, the direct or indirect assumption of management or control of financial activities, concessions, permissions, enterprises and public services for the purpose of deriving profit or wrongful advantages for themselves or others." The term Mafia type organizations is used to clearly distinguish the uniquely Sicilian Mafia from other criminal organizations – such as the Camorra, the 'Ndrangheta, the Sacra Corona Unita – that are structured like the Mafia, but are not the Mafia. According to historian Salvatore Lupo, “if everything is Mafia, nothing is Mafia.”

There are several lines of interpretation, often blended

to some extent, to define the Mafia: it has been viewed as

a mirror of traditional Sicilian society; as an enterprise

or type of criminal industry; as a more or less

centralized secret society; and/or as a juridical ordering

that is parallel to that of the state – a kind of anti -

state. The Mafia is all of these but none of these

exclusively.

Cosa Nostra is not a monolithic organization, but rather a loose confederation of about one hundred groups known alternately as "families", "cosche", "borgatas" or "clans" (despite the name, their members are generally not related by blood), each of which claims sovereignty over a territory, usually a town or village or a neighborhood of a larger city, though without ever fully conquering and legitimizing its monopoly of violence. For many years, the power apparatuses of the single families were the sole ruling bodies within the two associations, and they have remained the real centers of power even after superordinate bodies were created in the Cosa Nostra beginning in the late 1950s (the Sicilian Mafia Commission).

According to the Chief Prosecutor of Palermo, Francesco

Messineo, there were 94 Mafia clans in Sicily subject to

29 mandamenti, with a total of at least 3,500 to 4,000

full members. Most were based in western Sicily, almost

half of them in the province of Palermo.

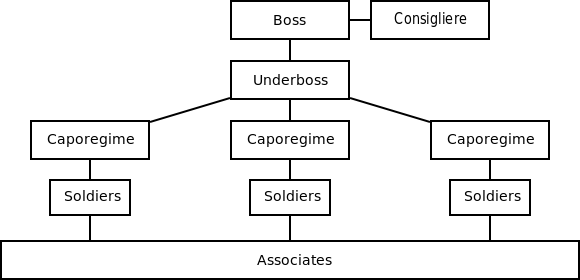

In 1984, the mafioso informant Tommaso Buscetta explained to prosecutors the command structure of a typical clan. A clan is led by a "boss" (capofamiglia or rappresentante), who is aided by an underboss (capo bastone or sotto capo) and supervised by one or more advisers (consigliere). Under his command are groups (decina) of about ten "soldiers" (soldati, operai or picciotti). Each decina is led by a capodecina.

The actual structure of any given clan can vary. Despite the name decina, they do not necessarily have ten soldiers, but can have anything from five to thirty. Some clans are so small that they don't even have decinas and capodecinas, and even in large clans certain soldiers may report directly to the boss.

The boss of a clan is typically elected by the rank - and - file soldiers (though violent successions do happen). Due to the small size of most Sicilian clans, the boss of a clan has intimate contact with all members, and doesn't receive much in the way of privileges or rewards as he would in larger organizations (such as the larger Five Families of New York). His tenure is also frequently short: elections are yearly, and he might be deposed sooner for misconduct or incompetence.

The underboss is usually appointed by the boss. He is the boss' most trusted right hand man and second - in - command. If the boss is killed or imprisoned, he takes over as leader.

The consigliere ("counselor") of the clan is also elected on a yearly basis. One of his jobs is to supervise the actions of the boss and his immediate underlings, particularly in financial matters (e.g., preventing embezzlement). He also serves as an impartial adviser to the boss and mediator in internal disputes. To fulfill this role, the consigliere must be impartial, devoid of conflict of interest and ambition.

Other than its members, Cosa Nostra makes extensive use of "associates". These are people who work for or aid a clan (or even multiple clans) but are not treated as true members. These include corrupt officials and prospective mafiosi. An associate is considered by the mafiosi nothing more than a tool, someone that they can "use", or "nothing mixed with nil."

The media has often made reference to a "capo di tutti

capi" or "boss of bosses" that allegedly "commands all of

Cosa Nostra". Calogero Vizzini, Salvatore Riina and

Bernardo Provenzano were especially influential bosses who

have each been described by the media and law enforcement

as being the "boss of bosses" of their times. While a

powerful boss may exert great influence over his

neighbors, the position does not formally exist, according

to Mafia turncoats such as Buscetta. According to Mafia

historian Salvatore Lupo "the emphasis of the media on the

definition of a 'capo di tutti capi' is without any

foundation".

Membership in Cosa Nostra is open only to Sicilian men. A candidate cannot be a relative or have any close links with a lawman, such as a policeman or a judge. There is no strict age limit: boys as young as sixteen have been initiated. A prospective mafioso is carefully tested for obedience, discretion, ruthlessness and skill at spying. He is almost always required to commit murder as his ultimate trial, even if he doesn't plan to be a career assassin. The act of murder is to prove his sincerity (i.e., he is not an undercover policeman) and to bind him into silence (i.e., he cannot break omertà without facing murder charges himself).

Traditionally, only men can become mafiosi, though in recent times there have been reports of women assuming the responsibilities of imprisoned mafiosi relatives.

Although clans are also called "families", their members are usually not related by blood. The Mafia actually has rules designed to prevent nepotism. Membership and rank in the Mafia are not hereditary. Most new bosses are not related to their predecessor. The Commission forbids relatives from holding positions in inter-clan bodies at the same time. That said, mafiosi frequently bring their sons into the trade. They have an easier time entering, because the son bears his father's seal of approval and is familiar with the traditions and requirements of Cosa Nostra.

A mafioso's legitimate occupation, if he has any,

generally does not affect his prestige within Cosa

Nostra. Historically, most

mafiosi were employed in menial jobs, and many bosses did

not work at all. Professionals such as lawyers and doctors

do exist within the organization, and are employed

according to whatever useful skills they have.

Since the 1950s, the Mafia has maintained multiple commissions to resolve disputes and promote cooperation among clans. Each province of Sicily has its own Commission. Clans are organized into districts (mandamenti) of three or four geographically adjacent clans. Each district elects a representative (capo mandamento) to sit on its Provincial Commission.

Contrary to popular belief, the commissions do not serve as a centralized government for the Mafia. The power of the commissions are limited and clans are autonomous and independent. Rather, each Commission serves as a representative mechanism for consultation of independent clans who decide by consensus. "Contrary to the wide - spread image presented by the media, these superordinate bodies of coordination cannot be compared with the executive boards of major legal firms. Their power is intentionally limited. And it would be entirely wrong to see in the Cosa Nostra a centrally managed, internationally active Mafia holding company," according to criminologist Letizia Paoli.

A major function of the Commission is to regulate the use of violence. For instance, a mafioso who wants to commit a murder in another clan's territory must ask the permission of the local boss; the commission enforces this rule. Any murder of a mafioso or prominent individual (police, lawyers, politicians, journalists, etc.) must be approved by the commission. Such acts can potentially upset other clans and spark a war, so the Commission provides a means by which to obtain their approval.

The Commission also deals with matters of succession.

When a boss dies or retires, his clan's reputation often

crumbles with his departure. This can cause clients to

abandon the clan and turn to neighboring clans for

protection. These clans would grow greatly in status and

power relative to their rivals, potentially destabilizing

the region and precipitating war. The Commission may

choose to divide up the clan's territory and members among

its neighbors. Alternatively, the commission has the power

to appoint a regent for

the clan until it can elect a new boss.

One of the first accounts of an initiation ceremony into the Mafia was given by Bernardino Verro, a leader of the Fasci Siciliani, a popular movement of democratic and socialist inspiration, which arose in Sicily in the early 1890s. In order to give the movement teeth and to protect himself from harm, Verro became a member of a Mafia group in Corleone, the Fratuzzi (Little Brothers). In a memoir written many years later, he described the initiation ritual he underwent in the spring of 1893:

"[I] was invited to take part in a secret meeting of the Fratuzzi. I entered a mysterious room where there were many men armed with guns sitting around a table. In the center of the table there was a skull drawn on a piece of paper and a knife. In order to be admitted to the Fratuzzi, [I] had to undergo an initiation consisting of some trials of loyalty and the pricking of the lower lip with the tip of the knife: the blood from the wound soaked the skull."—Bernardino Verro

After his arrest, the mafioso Giovanni Brusca described the ceremony in which he was formally made a full member of Cosa Nostra. In 1976 he was invited to a "banquet" at a country house. He was brought into a room where several mafiosi were sitting around a table upon which sat a pistol, a dagger and piece of paper bearing the image of a saint. They questioned his commitment and his feelings regarding criminality and murder (despite him already having a history of such acts). When he affirmed himself, Salvatore Riina, then the most powerful boss of Cosa Nostra, took a needle and pricked Brusca's finger. Brusca smeared his blood on the image of the saint, which he held in his cupped hands as Riina set it alight. As Brusca juggled the burning image in his hands, Riina said to him: "If you betray Cosa Nostra, your flesh will burn like this saint."

The elements of the ceremony have changed little over the

Mafia's history.

These elements have been the subject of much curiosity and

speculation. The sociologist Diego Gambetta points out

that the Mafia, being a secretive criminal organization,

cannot keep written records and thus cannot have its

recruits sign application forms and written contracts as

legitimate institutions do. Thus they rely on the old

fashioned ritual ceremony. The elements of the ceremony

are made deliberately specific, bizarre and painful so

that the event is both memorable and unambiguous, and the

ceremony is witnessed by a number of senior mafiosi. The

participants may not even care about what the symbols

mean, and they may indeed have no intrinsic meaning. The

real point of the ritual is to leave no doubt about the

mafioso's new status so that it cannot be denied or

revoked on a whim.

A mafioso is not supposed to introduce himself to another mafioso he does not personally know, even if both mafiosi know of each other through reputation, because there is a risk that the mafioso might accidentally expose himself to an outsider or undercover policeman. If he wants to establish a relationship, he must ask a third mafioso whom they both personally know to introduce them to each other in a face-to-face meeting. This intermediary can vouch that neither of the two is an impostor.

This tradition is upheld very scrupulously, often to the detriment of efficient operation. For instance, when the mafioso Indelicato Amedeo returned to Sicily following his initiation in America in the 1950s, he could not introduce himself to his own mafioso father, but had to wait for a mafioso from America who knew of his induction to come to Sicily.

Mafiosi of equal

status sometimes call each other "compare", while

inferiors call their superiors "padrino".

"Padrino" is the Italian term for "godfather".

In November 2007 Sicilian police reported discovery of a list of "Ten Commandments" in the hideout of mafia boss Salvatore Lo Piccolo, thought to be guidelines on good, respectful and honorable conduct for a mafioso.

- No one can present himself directly to another of our friends. There must be a third person to do it.

- Never look at the wives of friends.

- Never be seen with cops.

- Don't go to pubs and clubs.

- Always being available for Cosa Nostra is a duty - even if your wife is about to give birth.

- Appointments must absolutely be respected. (probably refers to formal rank and authority.)

- Wives must be treated with respect.

- When asked for any information, the answer must be the truth.

- Money cannot be appropriated if it belongs to others or to other families.

- People who can't be part of Cosa Nostra: anyone who has a close relative in the police, anyone with a two - timing relative in the family, anyone who behaves badly and doesn't hold to moral values.

The pentito Antonino Calderone recounted similar Commandments in his 1987 testimony:

These rules are not to touch the women of other men of honor; not to steal from other men of honor or, in general, from anyone; not to exploit prostitution; not to kill other men of honor unless strictly necessary; to avoid passing information to the police; not to quarrel with other men of honor; to maintain proper behavior; to keep silent about Cosa Nostra around outsiders; to avoid under all circumstances introducing oneself to other men of honor.

Omertà is a code of silence and secrecy that forbids mafiosi from betraying their comrades to the authorities. The penalty for transgression is death, and relatives of the turncoat may also be murdered. Mafiosi generally do not associate with police (aside perhaps from corrupting individual officers as necessary). For instance, a mafioso will not call the police when he is a victim of a crime. He is expected to take care of the problem himself. To do otherwise would undermine his reputation as a capable protector of others, and his enemies may see him as weak and vulnerable.

The need for secrecy and inconspicuousness deeply colors the traditions and mannerisms of mafiosi. Mafiosi are discouraged from consuming alcohol or drugs, as in an inebriated state they are more likely to blurt out sensitive information. They also frequently adopt self effacing attitudes to strangers so as to avoid unwanted attention. Whereas most Sicilians tend to be very verbose and expressive, mafiosi tend to be more terse and subdued. Mafiosi are also forbidden from writing down anything about their activities, lest such evidence be discovered by police.

To a degree, mafiosi also impose omertà on the general

population. Civilians who buy their protection or make

other deals are expected to be discreet, on pain of death.

Witness intimidation is also common.

Protection racketeering is one of the Sicilian Mafia's core activities. This aspect of the Mafia is often overlooked in the media because, unlike drug dealing and extortion, it is often not reported to the police. But many scholars, such as Diego Gambetta and Leopold Franchetti, see it as the Mafia's defining characteristic, the source of their power and place in Sicilian society. Gambetta describes the Mafia as a cartel of "private protection firms" who act as guarantors of trust and security in areas of the economy where such things are scarce and fragile. In exchange for money or favors, mafiosi use the credible threat of violence to protect their clients from fraudsters, thieves, and competitors.

For example: suppose a meat wholesaler wishes to sell some meat to a supermarket without paying taxes. Neither the seller nor buyer can turn to the police or the courts for help should something go wrong, such as the seller supplying rotten meat or the buyer not paying up. The law does not enforce black market agreements; it punishes them. Without the arbitration of the law, the seller could cheat the buyer with impunity or vice versa. If the parties both do not trust each other, they cannot do business and they could both lose out on a profitable deal. Instead, the parties can approach the local mafia clan to supervise their illegal deal. In exchange for a commission, the mafioso promises to both the buyer and seller that if either of them tries to cheat the other, the cheater can expect to be assaulted or have his property vandalized. Such is the mafioso's reputation for viciousness and reliability that neither the buyer nor the seller would consider cheating. Only a fool would dare cheat somebody protected by the Mafia. With the traders satisfied that this mafioso can discourage cheating, the transaction proceeds smoothly and all parties leave satisfied.

The Mafia's protection is not restricted to illegal activities. Shopkeepers often pay the Mafia to protect them from thieves. If a shopkeeper enters into a protection contract with a mafioso, the mafioso will make it publicly known that if any thief were foolish enough to rob his client's shop, he would track down the thief, beat him up, and, if possible, recover the stolen merchandise (mafiosi make it their business to know all the fences in their territory).

Mafiosi have protected a great variety of clients over the years: landowners, plantation owners, politicians, shopkeepers, drug dealers, etc. Whilst some people are coerced into buying protection and some do not receive any actual protection for their money (extortion), by and large there are many clients who actively seek and benefit from mafioso protection. This is one of the main reasons why the Mafia has resisted more than a century of government efforts to destroy it: the people who willingly solicit these services protect the Mafia from the authorities. If you are enjoying the benefits of Mafia protection, you do not want the police arresting your mafioso.

It is estimated that the Sicilian Mafia costs the Sicilian economy more than €10 billion a year through protection rackets. Roughly 70% of Sicilian businesses pay protection money to Cosa Nostra. Monthly payments can range from €200 for a small shop or bar to €5,000 for a supermarket. In Sicily, protection money is known as pizzo; the anti - extortion support group Addiopizzo derives its name from this. Mafiosi might sometimes ask for favors instead of money, such as assistance in committing a crime.

Protection from theft is one service that the Mafia

provides to paying "clients". Mafiosi themselves are

generally forbidden from committing theft

(though in practice they are merely forbidden from

stealing from anyone connected to the Mafia).

Instead, mafiosi make it their business to know all the

thieves and fences operating within their territory. If a

protected business is robbed, the clan will use these

contacts to track down and return the stolen goods and

punish the thieves, usually by beating them up. Since the

pursuit of thieves and their loot often goes into

territories of other clans, clans routinely cooperate with

each other on this matter, providing information and

blocking the sale of the loot if they can.

Mafiosi sometimes protect businessmen from competitors by threatening their competitors with violence. If two businessmen are competing for a government contract, the protected can ask his mafioso friends to bully his rival out of the bidding process. In another example, a mafioso acting on behalf of a coffee supplier might pressure local bars into serving only his client's coffee.

The primary method by which the Mafia stifles

competition, however, is the overseeing and enforcement of

collusive agreements between businessmen. Mafia enforced

collusion typically appear in markets where collusion is

both desirable (inelastic demand, lack of product

differentiation, etc.) and difficult to set up (numerous competitors, low barriers to

entry).

Industries which fit this description include garbage

collection.

Mafiosi approach potential clients in an aggressive but friendly manner, like a door - to - door salesman. They may even offer a few free favors as enticement. If a client rejects their overtures, mafiosi sometimes coerce them by vandalizing their property or other forms of harassment. Physical assault is rare; clients may be murdered for breaching agreements or talking to the police, but not for simply refusing protection.

In many situations, mafia bosses prefer to establish an indefinite long term bond with a client, rather than make one-off contracts. The boss can then publicly declare the client to be under his permanent protection (his "friend", in Sicilian parlance). This leaves little public confusion as to who is and isn't protected, so thieves and other predators will be deterred from attacking a protected client and prey only on the unprotected.

Mafiosi generally do not involve themselves in the management of the businesses they protect or arbitrate. Lack of competence is a common reason, but mostly it is to divest themselves of any interests that may conflict with their roles as protectors and arbitrators. This makes them more trusted by their clients, who need not fear their businesses being taken over.

A protection racketeer cannot tolerate competition

within his sphere of influence from another racketeer. If

a dispute erupted between two clients protected by rival

racketeers, the two racketeers would have to fight each

other to win the dispute for their respective client. The

outcomes of such fights can be unpredictable (not to

mention bloody), and neither racketeer could guarantee a

victory for his client. This would make their protection

unreliable and of little value. Their clients might

dismiss them and settle the dispute by other means, and

their reputations would suffer. To prevent this, mafia

clans negotiate territories in which they can monopolize

the use of violence in settling disputes.

This is not always done peacefully, and disputes over

protection territories are at the root of most Mafia wars.

Politicians court mafiosi to obtain votes during elections. A mafioso's mere endorsement of a certain candidate can be enough for his clients, relatives and associates to vote for said candidate. A particularly influential mafioso can bring in thousands of votes for a candidate; such is the respect a mafioso can command. The Italian Parliament has a huge number of seats (945, roughly 1 per 64,000 citizens) and a large number of political parties competing for them, meaning a candidate can win with only a few thousand votes. A mafia clan's support can thus be decisive for his success.

"Politicians have always sought us out because we can provide votes. [...] between friends and family, each man of honor can muster up forty to fifty other people. There are between 1,500 and 2,000 men of honor in Palermo province. Multiply that by fifty and you get a nice package of 75,000 to 100,000 votes to go to friendly parties and candidates."—Antonino Calderone

Politicians usually repay this support with favors, such as sabotaging police investigations or giving contracts and permits.

Although they are not ideological themselves, mafiosi

have traditionally opposed extreme parties such as

Fascists and Communists, and favored center candidates.

Mafiosi provide protection and invest capital in smuggling gangs. Smuggling operations require large investments (goods, boats, crews, etc.) but few people would trust their money to criminal gangs. It is mafiosi who raise the necessary money from investors and ensure all parties act in good faith. They also ensure that the smugglers operate in safety.

Mafiosi rarely directly involve themselves in smuggling operations. When they do, it is usually when the operations are especially risky. In this case, they may induct smugglers into their clans in the hope of binding them more firmly. This was the case with heroin smuggling, where the volumes and profits involved were too large to keep the operations at arm's length.

The Sicilian Mafia in Italy is believed to have a turnover of €6.5 billion through control of public and private contracts. Mafiosi use threats of violence and vandalism to muscle out competitors and win contracts for the companies they control. They rarely manage the businesses they control themselves, but take a cut of their profits, usually through payoffs (Pizzo).

In a 2007 publication, the Italian small-business association Confesercenti reported that about 25.2% of Sicilian businesses were indebted to loan sharks, who collected around €1.4 billion a year in payments. This figure has risen during the late 2000s recession, as tighter lending by banks forces the desperate to borrow from the Mafia.

Certain types of crimes are forbidden by Cosa Nostra, either by members or freelance criminals within their domains. Mafiosi are generally forbidden from committing theft (burglary, mugging, etc.). Kidnapping is also generally forbidden, even by non-mafiosi, as it attracts a great deal of public hostility and police attention. These rules have been violated from time to time, both with and without the permission of senior mafiosi.

Murders

are almost always carried out by members. It is very rare

for the Mafia to recruit an outsider for a single job, and

such people are liable to be eliminated soon afterwards

because they become expendable liabilities.

The Mafia's power comes from its reputation to commit violence, particularly murder, against virtually anyone and get away with it. Through reputation, mafiosi deter their enemies and enemies of their clients. It allows mafiosi to protect a client without being physically present (e.g., as bodyguards or watchmen), which in turn allows them to protect many clients at once.

Compared to other occupations, reputation is especially valuable for a mafioso, and they are especially vulnerable to blows in reputation. The reputation of a mafioso is dichotomous: he is either a good protector or a bad one; there is no mediocrity. This is because a mafioso can only either succeed at an act of violence or fail utterly. There is no spectrum of quality when it comes to violent protection. Consequently, a series of failures can completely ruin a mafioso's reputation, and with it his business.

The more fearsome a mafioso's reputation is, the more he can win disputes without having recourse to violence. It can even happen that a mafioso who loses his means to commit violence (e.g. his soldiers are all in prison) can still use his reputation to intimidate and provide protection if everyone is unaware of his weakness and still believes in his power. However, in the tough world of the Mafia, such bluffs generally do not last long, as his rivals will soon sense his weakness and challenge him.

When a Mafia boss retires from leadership (or is killed),

his clan's reputation as effective protectors and

enforcers often goes with him. If his replacement has a

weaker reputation, clients may lose confidence in the clan

and defect to its neighbors, causing a shift in the

balance of power and possible conflict. Ideally, the

successor to the boss will have built a strong reputation

of his own as he worked his way up the ranks, giving the

clan a reputable new leader. In this way,

established Mafia clans have a powerful edge over

newcomers who start from scratch; joining a clan as a

soldier offers an aspiring mafioso a chance to build up

his own reputation under the guidance and protection of

senior mafiosi.

Mafia violence is most commonly directed at other Mafia families competing for territory and business.

Violence is more common in the Sicilian Mafia than the American Mafia because Mafia families in Sicily are smaller and more numerous, creating a more volatile atmosphere.