<Back to Index>

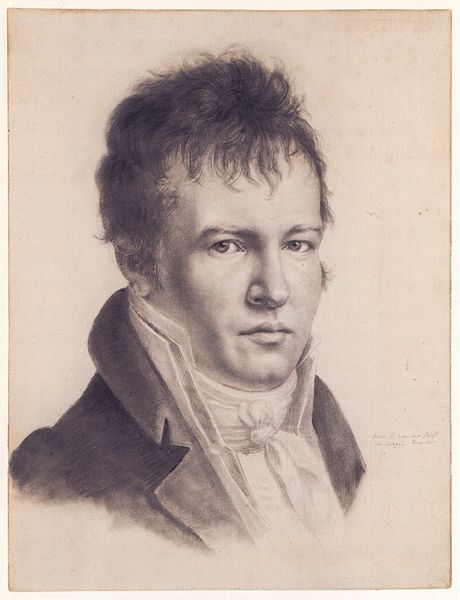

- Geographer, Naturalist and Explorer Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, 1769

- Philosopher and Diplomat Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt, 1767

PAGE SPONSOR

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (September 14, 1769 - May 6, 1859) was a Prussian geographer, naturalist and explorer, and the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767 - 1835). Humboldt's quantitative work on botanical geography laid the foundation for the field of biogeography.

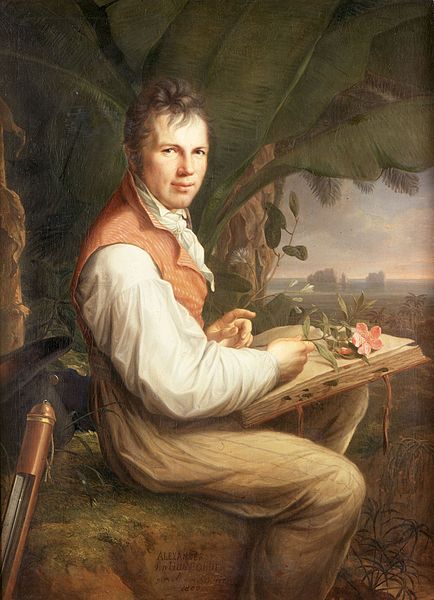

Between 1799 and 1804, Humboldt traveled extensively in

Latin America, exploring and describing it for the first

time in a manner generally considered to be a modern

scientific point of view. His description of the journey

was written up and published in an enormous set of volumes

over 21 years. He was one of the first to propose that the

lands bordering the Atlantic Ocean were once joined (South

America and Africa in particular). Later, his five volume

work, Kosmos (1845), attempted to unify the

various branches of scientific knowledge. Humboldt

supported and worked with other scientists, including Joseph - Louis Gay - Lussac,

Justus von Liebig, Louis Agassiz, Matthew Fontaine Maury

and Georg von Neumayer, most notably, Aimé Bonpland, with

whom he conducted much of his scientific exploration.

Humboldt was born in Berlin in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. His father, Alexander Georg von Humboldt, belonged to a prominent Pomeranian family; a major in the Prussian Army, he was rewarded for his services in the Seven Years' War with the post of Royal Chamberlain. He married the daughter of the Prussian general adjutant, von Schweder. In 1766, he married Maria Elizabeth Colomb, the widow of Baron von Hollwede, and they had two sons. The money of Baron von Holwede, left to his former wife, was instrumental in funding Alexander's explorations, contributing more than 70% of Alexander's income.

Due to his juvenile penchant for collecting and labeling plants, shells and insects, Alexander received the playful title of "the little apothecary". His father died in 1779, after which his mother saw to his education. Marked for a political career, he studied finance for six months at the University of Frankfurt (Oder); a year later, on April 25, 1789, he matriculated at Göttingen, then known for the lectures of C. G. Heyne and J. F. Blumenbach. His vast and varied interests were by this time fully developed, and during a vacation in 1789, he made a scientific excursion up the Rhine and produced the treatise Mineralogische Beobachtungen über einige Basalte am Rhein (Brunswick, 1790) (Mineralogic Observations on Several Basalts on the River Rhine).

Humboldt's passion for travel was confirmed by a friendship formed at Göttingen with Georg Forster, Heyne's son - in - law and the companion of Captain James Cook on Cook's second voyage. Thereafter, his talents were devoted to the purpose of preparing himself as a scientific explorer. With this emphasis, he studied commerce and foreign languages at Hamburg, geology at Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg under A. G. Werner, anatomy at Jena under J. C. Loder and astronomy and the use of scientific instruments under F. X. von Zach and J. G. Köhler. His researches into the vegetation of the mines of Freiberg led to the publication, in 1793, of his Florae Fribergensis Specimen. Long experimentation on muscular irritability, then recently discovered by Luigi Galvani, were contained in his Versuche über die gereizte Muskel- und Nervenfaser (Berlin, 1797) (Experiments on the Frayed Muscle and Nerve Fibres), enriched in the French translation with notes by Blumenbach.

In 1794 Humboldt was admitted to the famous Weimar coterie and contributed (June 7, 1795) to Schiller's new periodical, Die Horen, a philosophical allegory entitled Die Lebenskraft, oder der rhodische Genius. In the summer of 1790 he paid a short visit to England in the company of Forster. In 1792 and 1797 he was in Vienna; in 1795 he made a geological and botanical tour through Switzerland and Italy. He had obtained in the meantime official employment by appointment as assessor of mines at Berlin, February 29, 1792. Although this service to the state was regarded by him as only an apprenticeship to the service of science, he fulfilled its duties with such conspicuous ability that not only did he rise rapidly to the highest post in his department, but he was also entrusted with several important diplomatic missions. The death of his mother, on November 19, 1796, set him free to follow the bent of his genius, and severing his official connections, he waited for an opportunity to fulfill his long cherished dream of travel.

On the postponement of Captain Nicolas Baudin's proposed

voyage of circumnavigation, which he had been officially

invited to accompany, Humboldt left Paris for Marseille

with Aimé Bonpland, the designated botanist of the

frustrated expedition, hoping to join Napoleon Bonaparte in Egypt.

Means of transport, however, were not forthcoming, and the

two travelers eventually found their way to Madrid, where

the unexpected patronage of the minister Don Mariano Luis

de Urquijo convinced them to make Spanish America the

scene of their explorations.

Armed with powerful recommendations from the King of Spain, they sailed in the Pizarro from A Coruña, on June 5, 1799, stopped six days on the island of Tenerife to climb the volcano Teide, and landed at Cumaná, Venezuela, on July 16. Humboldt visited the mission at Caripe and explored the Guácharo cavern, where he found the oil-bird, which he was to make known to science as Steatornis caripensis. Returning to Cumaná, Humboldt observed, on the night of November 11-12, a remarkable meteor shower (the Leonids). He proceeded with Bonpland to Caracas where he would climb the Avila mount with Andres Bello. In February 1800, Humboldt and Bonpland left the coast with the purpose of exploring the course of the Orinoco River. This trip, which lasted four months and covered 1,725 miles (2,776 km) of wild and largely uninhabited country, had the important result of establishing the existence of the Casiquiare canal (a communication between the water systems of the rivers Orinoco and Amazon), and of determining the exact position of the bifurcation, as well as documenting the life of several native tribes such as the Maipures and their extinct rivals the Atures (several words of the latter tribe were transferred to Humboldt by one parrot). Around March 19, 1800, von Humboldt and Bonpland discovered and captured some electric eels. They both received potentially dangerous electric shocks during their investigations. Two months later they explored the territory of the Maypures and that of the then recently extinct Aturès Indians.

On November 24, the two friends set sail for Cuba where they met fellow botanist and plant collector John Fraser, and after a stay of some months they regained the mainland at Cartagena, Colombia. Ascending the swollen stream of the Magdalena River and crossing the frozen ridges of the Cordillera Real, they reached Quito on January 6, 1802, after a tedious and difficult journey. Their stay there was marked by the ascent of Pichincha and an attempt on Chimborazo. Humboldt and his party reached an altitude of 19,286 feet (5,878 m), a world record at the time. The journey concluded with an expedition to the sources of the Amazon en route for Lima, Peru. At Callao, Humboldt observed the transit of Mercury on November 9, and studied the fertilizing properties of guano, the subsequent introduction of which into Europe was due mainly to his writings. A tempestuous sea voyage brought them to Mexico, where they resided for a year, traveling to different cities.

Next, Humboldt made a short visit to the United States, staying in the White House as a guest of President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, a scientist himself, was delighted to have Humboldt as a guest and the two held numerous intense discussions on scientific matters. After six weeks, Humboldt set sail for Europe from the mouth of the Delaware and landed at Bordeaux on August 3, 1804.

This memorable expedition may be regarded as having laid

the foundation of the sciences of physical geography and

meteorology. By his delineation (in 1817) of "isothermal

lines", he at once suggested the idea and devised the

means of comparing the climatic conditions of various

countries. He first investigated the rate of decrease in

mean temperature with the increase in elevation above sea

level, and afforded, by his inquiries regarding the origin

of tropical storms, the earliest clue to the detection of

the more complicated law governing atmospheric

disturbances in higher latitudes; while his essay on the

geography of plants was based on the then novel idea of

studying the distribution of organic life as affected by

varying physical conditions. His discovery of the decrease

in intensity of Earth's magnetic field from the poles to

the equator was communicated to the Paris Institute in a

memoir read by him on December 7, 1804, and its importance

was attested by the speedy emergence of rival claims. His

services to geology were based mainly on his attentive

study of the volcanoes of the New World. He showed that

they fell naturally into linear groups, presumably

corresponding with vast subterranean fissures; and by his

demonstration of the igneous origin of rocks previously

held to be of aqueous formation, he contributed largely to

the elimination of erroneous views, such as Neptunism.

Humboldt is considered to be the "second discoverer of Cuba" due to all the scientific and social research he conducted on this Spanish colony. During an initial three-month stay at Havana, his first tasks were to properly survey that city and the nearby towns of Guanabacoa, Regla and Bejucal. He befriended Cuban landowner and thinker Francisco Arango y Parreño; together they visited the Guines area in south Havana, the valleys of Matanzas Province and the Valley of the Sugar Mills in Trinidad. Those three areas were, at the time, the first frontier of sugar production in the island. During those trips, Humboldt collected statistical information on Cuba's population, production, technology and trade, and with Arango, made suggestions for enhancing them. He predicted that the agricultural and commercial potential of Cuba was huge and could be vastly improved with proper leadership in the future. After traveling to the United States, Humboldt returned to Cuba for a second, shorter stay in April 1804. During this time he socialized with his scientific and landowner friends, conducted mineralogical surveys and finished his vast collection of the island's flora and fauna.

Finally, Humboldt conducted a rudimentary census of the indigenous and European inhabitants in New Spain, and on May 5, 1804, he estimated the population to be six million individuals.

The editing and publication of the encyclopedic mass of scientific, political and archaeological material that had been collected by him during his absence from Europe was now Humboldt's most urgent desire. After a short trip to Italy with Gay - Lussac for the purpose of investigating the law of magnetic declination and a sojourn of two and a half years in his native city, he finally, in the spring of 1808, settled in Paris with the purpose of securing the scientific cooperation required for bringing his great work through the press. This colossal task, which he at first hoped would occupy but two years, eventually cost him twenty-one, and even then it remained incomplete. In these early years in Paris, he shared accommodation and a laboratory with his former rival, and now friend, Joseph-Louis Gay - Lussac, both working together on the analysis of gases and the composition of the atmosphere.

Alexander von Humboldt thought an approach to science was needed that could account for the harmony of nature among the diversity of the physical world. For Humboldt, "the unity of nature" meant that it was the interrelation of all physical sciences — such as the conjoining between biology, meteorology and geology — that determined where specific plants grew. He found these relationships by unraveling myriad, painstakingly collected data, data extensive enough that it became an enduring foundation upon which others could base their work. Humboldt viewed nature holistically, and tried to explain natural phenomena without the appeal to religious dogma. He believed in the central importance of observation, and as a consequence had amassed a vast array of the most sophisticated scientific instruments then available. Each had its own velvet lined box and was the most accurate and portable of its time; nothing quantifiable escaped measurement. According to Humboldt, everything should be measured with the finest and most modern instruments and sophisticated techniques available, for it was that collected data was the basis of all scientific understanding. This quantitative methodology would become known as "Humboldtian science." Humboldt wrote "Nature herself is sublimely eloquent. The stars as they sparkle in firmament fill us with delight and ecstasy, and yet they all move in orbit marked out with mathematical precision."

His critics say his writings contain fantastical descriptions of America, while leaving out its inhabitants. They claim Humboldt, coming from the Romantic school of thought, believed '...nature is perfect till man deforms it with care.' In this line of thinking, they think he largely neglected the human societies amidst this nature. The writing style that describes the 'new world' without people is a trend among explorers both of the past and present. Views of indigenous peoples as 'savage' or 'unimportant' leaves them out of the historical picture. In reality Humboldt dedicated large parts of his work to describing the conditions of slaves, Indians and society in general. He often showed his disgust for the slavery and inhumane conditions in which Indians and others were treated and he often criticized the colonial policies. Some of Humboldt's descriptions or assumptions were not accurate.

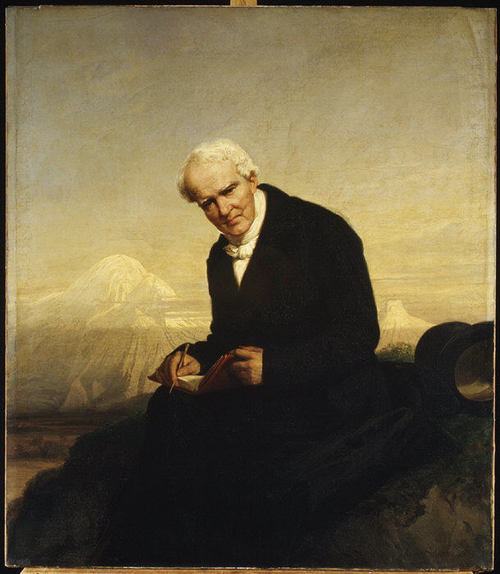

Humboldt was now one of the most famous men in

Europe. The acclaimed American painter Rembrandt Peale

painted him during his European stay, between 1808 and

1810, as one of the most prominent figures in Europe at

the time. A chorus of applause greeted him from every

side. Academies, both native and foreign, were eager to

enroll him among their members. He was elected a foreign

member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1810.

King Frederick William III of Prussia conferred upon him

the honor, without exacting the duties, attached to the

post of royal chamberlain, together with a pension of

2,500 thalers, afterwards doubled. He refused the

appointment of Prussian minister of public instruction in

1810. In 1814 he accompanied the allied sovereigns to

London. Three years later he was summoned by the king of

Prussia to attend him at the congress of Aachen. Humboldt

was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American

Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822. Again in the autumn

of 1822 he accompanied the same monarch to the Congress of

Verona, proceeded thence with the royal party to Rome and

Naples and returned to Paris in the spring of 1823.

Humboldt had long regarded the French capital as his true home. There he found not only scientific sympathy, but the social stimulus which his vigorous and healthy mind eagerly craved. He was equally in his element as the lion of the salons and as the savant of the Institut de France and the observatory. During that time he met in 1818, the young and brilliant Peruvian student of the Royal Mining School of Paris, Mariano Eduardo de Rivero y Ustariz. They became good friends. Subsequently von Humboldt acted as a mentor of the career of this promising Peruvian scientist. Thus, when at last he received from his sovereign a summons to join his court at Berlin, he obeyed indeed, but with deep and lasting regret. The provincialism of his native city was odious to him. He never ceased to rail against the bigotry without religion, aestheticism without culture, and philosophy without common sense, which he found dominant on the banks of the Spree. The unremitting benefits and sincere attachment of two well meaning princes secured his gratitude but could not appease his discontent. At first he sought relief from the "nebulous atmosphere" of his new abode by frequent visits to Paris; but as years advanced, his excursions were reduced to accompanying the monotonous "oscillations" of the court between Potsdam and Berlin. On May 12, 1827, he settled permanently in the Prussian capital, where his first efforts were directed towards the furtherance of the science of terrestrial magnetism. For many years, it had been one of his favorite schemes to secure, by means of simultaneous observations at distant points, a thorough investigation of the nature and law of "magnetic storms" (a term invented by him to designate abnormal disturbances of Earth's magnetism). The meeting at Berlin, on September 18, 1828, of a newly formed scientific association, of which he was elected president, gave him the opportunity of setting on foot an extensive system of research in combination with his diligent personal observations. His appeal to the Russian government, in 1829, led to the establishment of a line of magnetic and meteorological stations across northern Asia. Meanwhile his letter to the Duke of Sussex, then (April 1836) president of the Royal Society, secured for the undertaking, the wide basis of the British dominions.

The Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition, observes, "Thus that scientific conspiracy of nations which is one of the noblest fruits of modern civilization was by his exertions first successfully organized." However, earlier examples of international scientific cooperation exist, notably the 18th century observations of the transits of Venus.

Then President of Mexico, Benito Juárez, gave him honorary Mexican citizenship.

In 1811, and again in 1818, projects of Asiatic

exploration were proposed to Humboldt, first by the

Russian government, and afterwards by the Prussian

government; but on each occasion, untoward circumstances

interposed, and it was not until he had begun his sixtieth

year that he resumed his early role of traveler in the

interests of science. Between May and November 1829, he,

together with his chosen associates, Gustav Rose and C. G. Ehrenberg, traversed

the wide expanse of the Russian empire from the Neva to

the Yenesei, accomplishing in twenty-five weeks a distance

of 9,614 miles (15,472 km). The journey, however, though

carried out with all the advantages afforded by the

immediate patronage of the Russian government, was too

rapid to be profitable. The correction of the prevalent

exaggerated estimate of the height of the Central Asian

plateau, and the discovery of diamonds in the gold -

washings of the Ural, a result which Humboldt's Brazilian

experiences enabled him to predict, and by predicting to

secure.

Between 1830 and 1848 von Humboldt was frequently employed in diplomatic missions to the court of Louis Philippe, with whom he always maintained the most cordial personal relations.

His brother, Wilhelm von Humboldt, died in Alexander's arms on April 8, 1835. The death saddened the later years of his life; Alexander lamented that he had lost half of himself with the death of his brother.

Upon the accession of the crown prince Frederick William

IV in June 1840, Humboldt's favor at court increased.

Indeed, the new king's craving for Humboldt's company

became at times so importunate as to leave him only a few

waking hours to work on his writing.

The first two volumes of the Kosmos were published between the years 1845 and 1847. Humboldt had long intended to write a comprehensive work about geography and the natural sciences. The writing took shape in lectures he delivered before the University of Berlin in the winter of 1827-28. These lectures would form "the cartoon for the great fresco of the [K]osmos". The work attempted to unify the sciences then known in a Kantian framework. With inspiration from German Romanticism, Humboldt sought to create a compendium of the world's environment.

He spent the last decade of his long life — as he called them, his "improbable" years — continuing this work. The third and fourth volumes were published in 1850-58; a fragment of a fifth appeared posthumously in 1862.

Kosmos was very popular in Britain and America. In 1849 a German newspaper commented that in England two of the three different translations were made by women, "while in Germany most of the men do not understand it." The first translation by Augustin Pritchard — published anonymously by Mr. Baillière (volume I in 1845 and volume II in 1848) — suffered from being hurriedly made. In a letter Humboldt said of it: "It will damage my reputation. All the charm of my description is destroyed by an English sounding like Sanskrit."

The other two translations were made by Mrs. Sabine under the superintendence of her husband Col. Edward Sabine (4 volumes 1846 - 1858), and by Miss E.C. Otté (5 volumes 1849 - 1858, the only complete translation of the 4 German volumes). These three translations were also published in America. The numbering of the volumes differs between the German and the English editions. Volume 3 of the German edition corresponds to the volumes 3 and 4 of the English translation, as the German volume appeared in 2 parts in 1850 and 1851. Volume 5 of the German edition was not translated until 1981, again by a woman. Miss Otté's translation benefited from a detailed table of contents, and an index for every volume; of the German edition only volumes 4 and 5 had a (extremely short) tables of contents, and the index to the whole work only appeared with volume 5 in 1862.

Not so well known in Germany is the atlas belonging to the German edition of the Cosmos "Berghaus’ Physikalischer Atlas", better known as the pirated version by Traugott Bromme under the title "Atlas zu Alexander von Humboldt's Kosmos" (Stuttgart 1861). In Britain Heinrich Berghaus planned to publish together with Alexander Keith Johnston a "Physical Atlas". But later Johnston published it alone under the title "The Physical Atlas of Natural Phenomena". In Britain its connection to the Cosmos seems not have been recognized.

On

February 24, 1857, Humboldt suffered a minor stroke, which

passed without perceptible symptoms. It was not until the

winter of 1858 - 1859 that his strength began to decline,

and that spring, on May 6, he died quietly in Berlin at

the age of 89. The honors which had been showered on him

during life continued after his death. His remains, prior

to being interred in the family resting place at Tegel,

were conveyed in state through the streets of Berlin, and

received by the prince - regent at the door of the

cathedral. The first centenary of his birth was celebrated

on September 14, 1869, with great enthusiasm in both the

New and Old Worlds. Numerous monuments were constructed in

his honour, and newly explored regions named after

Humboldt, bear witness to his wide fame and popularity.

Much of Humboldt's private life remains a mystery because he destroyed his private letters.

In 1908 the sexual researcher Paul Näcke, who worked with

outspoken gay activist Magnus Hirschfeld, gathered

reminiscences of him from people who recalled his

participation in the homosexual

subculture of Berlin. A traveling

companion, the pious Francisco José de Caldas, accused him

of frequenting houses where 'impure love reigned', of

making friends with 'obscene dissolute youths', and giving

vent to 'shameful passions of his heart'.

But author Robert F. Aldrich concludes hesitantly: "As for

so many men of his age, a definite answer is impossible."

Throughout his life Humboldt formed strong emotional attachments to men. In a letter to Reinhard von Haeften, a soldier, he wrote: "I know that I live only through you, my good precious Reinhard, and that I can only be happy in your presence." He never married, yet there were at least two notable occasions where he seemed to have been drawn to the opposite sex. The first was an adolescent infatuation with Henriette Herz, the beautiful wife of Marcus Herz, his mentor, and the second was a short lived but intimate relationship with a woman named Pauline Wiesel in 1808 Paris. He was strongly attached to his brother's family. Four years before his death, he executed a deed of gift transferring the absolute possession of his entire property to an old family servant named Seifert.

Humboldt made many friends and had a reputation for

widespread benevolence. He showed zeal for the improvement

of the condition of the miners in Galicia and Franconia,

detestation of slavery, and patronage of rising men of

science.

Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt (22 June 1767 - 8 April 1835) was a Prussian philosopher, government functionary, diplomat, and founder of the University of Berlin, which was named after him (and his brother, naturalist Alexander von Humboldt) in 1949. He is especially remembered as a linguist who made important contributions to the philosophy of language and to the theory and practice of education. In particular, he is widely recognized as having been the architect of the Prussian education system which was used as a model for education systems in countries such as the United States and Japan.

Humboldt was born in Potsdam, Margraviate of Brandenburg,

and died in Tegel, Province of Brandenburg. His younger brother, Alexander von

Humboldt, was equally famous, as a geographer and

explorer.

Humboldt was a philosopher and wrote On the Limits of State Action in 1791-2 (though it was not published until 1850, after Humboldt's death), one of the boldest defenses of the liberties of the Enlightenment. It influenced John Stuart Mill's essay On Liberty through which von Humboldt's ideas became known in the English-speaking world. Humboldt outlined an early version of what Mill would later call the "harm principle".

The section dealing with education was published in the

December 1792 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift under

the title ‘On public state education’. With this

publication, Humboldt took part in the philosophical

debate on the direction of national education which was in

progress in Germany, as elsewhere after the French

Revolution.

As Prussian Minister of Education, Humboldt oversaw the system of Technische Hochschulen and Gymnasien. Humboldt's plans for reforming the Prussian school system were not published until long after his death, together with his fragment of a treatise on the 'Theory of Human Education', which had been written in about 1793. Here Humboldt states that 'the ultimate task of our existence is to give the fullest possible content to the concept of humanity in our own person [...] through the impact of actions in our own lives'. This task 'can only be implemented through the links established between ourselves as individuals and the world around us' (GS, I, p. 283).

Humboldt's concept of education does not lend itself solely to individualistic interpretation. It is true that he always recognized the importance of the organization of individual life and the 'development of a wealth of individual forms' (GS, III, p. 358), but he stressed the fact that 'self - education can only be continued [...] in the wider context of development of the world' (GS, VII, p. 33). In other words, the individual is not only entitled, but also obliged, to play his part in shaping the world around him.

Humboldt's educational ideal was entirely colored by

social considerations. He never believed that the 'human

race could culminate in the attainment of a general

perfection conceived in abstract terms'. In 1789, he wrote

in his diary that 'the education of the individual

requires his incorporation into society and involves his

links with society at large' (GS, XIV, p. 155). In his

essay on the 'Theory of Human Education', he answered the

question as to the 'demands which must be made of a

nation, of an age and of the human race'. 'Education,

truth and virtue' must be disseminated to such an extent

that the 'concept of mankind' takes on a great and

dignified form in each individual (GS, I, p. 284).

However, this shall be achieved personally by each

individual, who must 'absorb the great mass of material

offered to him by the world around him and by his inner

existence, using all the possibilities of his

receptiveness; he must then reshape that material with all

the energies of his own activity and appropriate it to

himself so as to create an interaction between his own

personality and nature in a most general, active and

harmonious form' (GS, II, p. 117). In the original text

from which this section has been lifted without

attribution, "GS" refers to Humboldt, Wilhelm von.

1903-36. Gesammelte Schriften: Ausgabe Der Preussischen

Akademie Der Wissenschaften. Bd. I-XVII, Berlin. (Cited as

GS in the text, the Roman numeral indicates the volume and

the Arabic figure the page; the original German spelling

has been modernized.) "Gesammelte Schriften" means

"Collected Writings".

As a successful diplomat between 1802 and 1819, Humboldt

was plenipotentiary Prussian minister at Rome from 1802,

ambassador at Vienna from 1812 during the closing

struggles of the Napoleonic Wars, at the congress of

Prague (1813) where he was instrumental in drawing Austria

to ally with Prussia and Russia against France, a signer

of the peace treaty at Paris and the treaty between

Prussia and defeated Saxony (1815), at Frankfurt settling

post Napoleonic Germany, and at the congress at Aachen in

1818. However, the increasingly reactionary policy of the

Prussian government made him give up political life in

1819; and from that time forward he devoted himself solely

to literature and study.

Wilhelm von Humboldt was an adept linguist and studied the Basque language. He translated Pindar and Aeschylus into German.

Humboldt's work as a philologist in Basque has had more extensive impact than his other work. His visit to the Basque country resulted in Researches into the Early Inhabitants of Spain by the help of the Basque language (1821). In this work, Humboldt endeavored to show by examining geographical place names, that at one time a race or races speaking dialects allied to modern Basque extended throughout Spain, southern France and the Balearic Islands; he identified these people with the Iberians of classical writers, and further surmised that they had been allied with the Berbers of northern Africa. Humboldt's pioneering work has been superseded in its details by modern linguistics and archaeology, but is sometimes still uncritically followed even today.

Humboldt died while preparing his greatest work, on the ancient Kawi language of Java, but its introduction was published in 1836 as The Heterogeneity of Language and its Influence on the Intellectual Development of Mankind. This essay on the philosophy of speech:

- "... first clearly laid down that the character and structure of a language expresses the inner life and knowledge of its speakers, and that languages must differ from one another in the same way and to the same degree as those who use them. Sounds do not become words until a meaning has been put into them, and this meaning embodies the thought of a community. What Humboldt terms the inner form of a language is just that mode of denoting the relations between the parts of a sentence which reflects the manner in which a particular body of men regards the world about them. It is the task of the morphology of speech to distinguish the various ways in which languages differ from each other as regards their inner form, and to classify and arrange them accordingly." 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

He is credited with being the first European linguist to identify human language as a rule - governed system, rather than just a collection of words and phrases paired with meanings. This idea is one of the foundations of Noam Chomsky's theory of language. Chomsky frequently quotes Humboldt's description of language as a system which "makes infinite use of finite means", meaning that an infinite number of sentences can be created using a finite number of grammatical rules. Humboldt scholar Tilman Borsche notes profound differences between von Humboldt's view of language and Chomsky's.

More recently Humboldt has also been credited as an originator of the linguistic relativity hypothesis (more commonly known as the Sapir – Whorf hypothesis), developed by linguists Edward Sapir or Benjamin Whorf a century later. Nonetheless, the reception of Humboldt's work remains problematic in English-speaking countries, despite the work of Langham Brown, Manchester and Underhill (Humboldt, Worldview & Language, 2009). Indeed, although encyclopédias often cite Humboldt as being the founder of the term 'worldview', a confusion is invariably made by citing the German term Weltanschauung, which is rightly associated with ideologies and cultural mindsets in both German and English. Humboldt's work was concerned more with what he called Weltansicht, the linguistic worldview. This distinction was cleared up by one of the leading contemporary German Humboldt scholars, Jürgen Trabant, in his works in both German and French. Polish linguists,working in the Lublin School (see Jerzy Bartmiński) preserve this distinction between worldviews of a personal or political kind and the worldview implicit in the language as a conceptual system, in their reading of Humboldt and in their research into the Polish - speaker's worldview.

However, little rigorous research in English has gone into exploring the relationship between the linguistic worldview and the transformation and maintenance of this worldview by individual speakers. One notable exception is the work of Underhill who explores comparative linguistic studies in both Creating Worldviews: Language, Ideology & Metaphor (2011) and in Ethnolinguistics and Cultural Concepts: Truth, Love, Hate & War. In Underhill's work, a distinction is made between five forms of worldview: world - perceiving, world - conceiving, cultural mindset, personal world and perspective, in order to convey the distinctions Humboldt was concerned with preserving in his ethnolinguistics. Probably the best known linguist working with a truly Humboldtian perspective writing in Englishis Anna Wierzbicka who has published a wide number of comparative works on semantic universals and conceptual distinctions in language.

In June 1791 Humboldt married Karoline von Dacheröden. They had eight children. Five survived to adulthood.