<Back to Index>

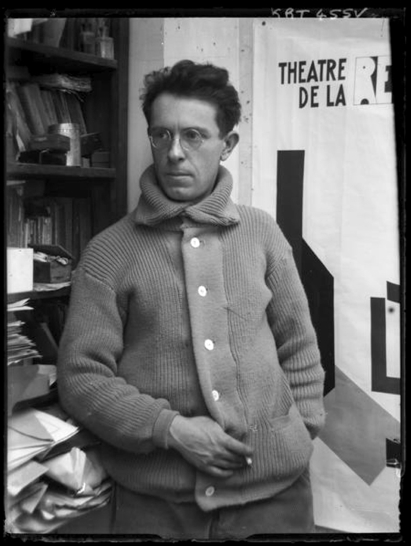

- Sculptor Joseph Csaky, 1888

PAGE SPONSOR

Joseph Csaky (also written Josef Csŕky', Csáky József and József Csáky) (Szeged, March 18, 1888 - Paris, May 1, 1971) was a Hungarian avant garde artist, sculptor and graphic artist, best known for his early participation as a sculptor in the Cubist movement. Joseph Csaky was one of the first sculptors in Paris to apply the principles of pictorial Cubism to his art, and was a pioneer of modern sculpture. He was an active member of the Section d'Or group between 1911 and 1914, and closely associated with De Stijl and Purism throughout the 1920s.

Csaky fought alongside French soldiers during World War I and in 1922 became a naturalized French citizen. He was a founding member of l'Union des Artistes modernes (UAM) in 1929. During World War II, Csaky joined forces with the French underground movement (la Résistance) in Valençay. In the late 1920s, he collaborated with some other artists in designing furniture and other decorative pieces, including elements of the Studio House for the designer Jacques Doucet.

After 1928, Csaky moved away from Cubism into a more

figurative or representational style for nearly thirty

years. He exhibited internationally across Europe, but

some of his pioneering artistic innovation was forgotten.

His work today is primarily held by French and Hungarian

institutions, as well as galleries and private collections

both in France and abroad.

József Csáky was born in Szeged, Hungary, then part of the dual monarchy of the Austro - Hungarian Empire. A provincial southern city, Szeged is now the third largest in the country.

Csaky moved with his family to Budapest at an early age, where he frequented museums and galleries. In 1905 Csaky was accepted at the Academy of Applied Arts in Budapest, where he studied under the direction of the sculptor Mátrai Lajos (1875 - 1945) for one and a half years. His interest centered around figure drawing, but, dissatisfied with the local traditional art training (which consisted of copying sculptures in plaster and modeling wild flowers out of clay), Csaky and fellow students left the school to study in the workshop of the photographer - painter László Kimnach, in Buda.

In 1907, for six and a half months, he worked in the

Zsolnay Factory in Pécs, making ceramic ashtrays and

vases. He worked briefly as a metal founder in Budapest,

and at one point with a taxidermist. Attracted by its

reputation for lights and great artists, Csaky made the

decision to move to Paris France, and did so (with only

forty francs in his pocket. He traveled mostly by

foot, walking fifty or sixty kilometers per day during the

summer of 1908. In Paris a 'new world' opened up for him.

He made a living by doing odd jobs: working as a peddler,

stone cutter, and posing as a model for students at a

local art school, making 20 francs a week. He later posed

for individual artists in their own studios, making more

money and leaving plenty of time free to pursue his own

work. By autumn of 1908

he shared a studio space at Cité Falguičre with Joseph

Brummer, a Hungarian friend who had opened the Brummer

Gallery with his brothers and was studying art. Within

three weeks of Csaky's arrival in Paris, Brummer showed

the newcomer a sculpture he was working on: an exact copy

of an African sculpture from the Congo. Brummer told Csaky

that another artist in Paris, a Spaniard named Pablo

Picasso, was painting in the spirit of 'Negro' sculptures.

Shortly after, Csaky found a studio at the artists' collective La Ruche in Montparnasse. The building had been constructed by Gustave Eiffel, and was adapted as artists' studios by the sculptor Alfred Boucher. Among other émigré artists at La Ruche were Alexander Archipenko (who arrived in Paris the same year), Wladimir Baranoff - Rossine, and Sonia Delaunay (Terk). In the early years of the 20th century, other artists who lived there for a time included Guillaume Apollinaire, Ossip Zadkine, Moise Kisling, Marc Chagall, Max Pechstein, Fernand Léger, Jacques Lipchitz, Max Jacob, Blaise Cendrars, Chaim Soutine, Robert Delaunay, Amedeo Modigliani, Constantin Brâncuşi and Diego Rivera, attracted to Paris from across Europe and Mexico.

Soon Csaky and his new Parisian girlfriend Jeanne moved into a studio together on rue Didot, near the Pasteur Institute and Montparnasse Cemetery. They married.

"Thinking back on my life now," Csaky would later write, "I am amazed by the speed of the events. A few months before I had been a poor and helpless fellow who had found himself in a strange country all alone, not even speaking the language. And then, all of a sudden, from one minute to the next, I became a man with an orderly life, a place of his own and a wife, an honest, and good working woman." (Joseph Csaky)

This relationship did not last long. The two separated

but retained a friendship. Csaky rented a small attic

studio on rue Dalou. In 1910 Csaky won the Ferenc

József Art Scholarship in Szeged, giving him enough

money to attend l'Académie de la Palette, a private school

in Paris. He was able to devote himself full time to art.

"Csaky, after Archipenko, was the first sculptor to join the cubists, with whom he exhibited from 1911 on. They were followed by Duchamp - Villon [...] and then in 1914 by Lipchitz, Laurens and Zadkine." (Michel Seuphor)

The inspirations that led Csaky to Cubism were diverse, as they were for artists of the Bateau - Lavoir, on the one hand, or the Puteaux Group on the other. While art historians are divided on the influence of African art in the distillation of Cubism, they generally agree that Cézanne's geometric syntax was significant, as well as Seurat's approach to painting. Given a growing dissatisfaction with the classical methods of representation, and the contemporary changes — the industrial revolution, exposure to art from across the world — artists began to transform their expression.

Archipenko and Csaky — along with the Cubist sculptors who would follow — stimulated by the profound cultural changes and their own experiences, contributed their own personal artistic language.

Csaky wrote of the direction his art had taken during the crucial years:

"There was no question which was my way. True, I was not alone, but in the company of several artists who came from Eastern Europe. I joined the cubists in the Académie La Palette, which became the sanctuary of the new direction in art. On my part I did not want to imitate anyone or anything. This is why I joined the cubists movement." (Joseph Csaky)

Early in his artistic career, Csaky had understood that Cubism was a great liberating force. It was a means of reassessing the nature of sculpture as a four - dimensional continuum, with space, mass, plane and direction, dynamic and changing in time. It represented for him the departure from classicism, from the conventions of his predecessors.

Csaky first met Picasso at the gallery of Daniel - Henry Kahnweiler. He had already met Guillaume Apollinaire but was never as close to either of them as to Archipenko, Henri Laurens, Jacques Villon, Raymond Duchamp - Villon, and Jean Metzinger. They often met at Henri Le Fauconnier's studio on rue Notre - Dame - des - Champs, near the Boulevard de Montparnasse, as well as at the Montjoie, Café de la Rotonde and La Closerie des Lilas in Montparnasse.

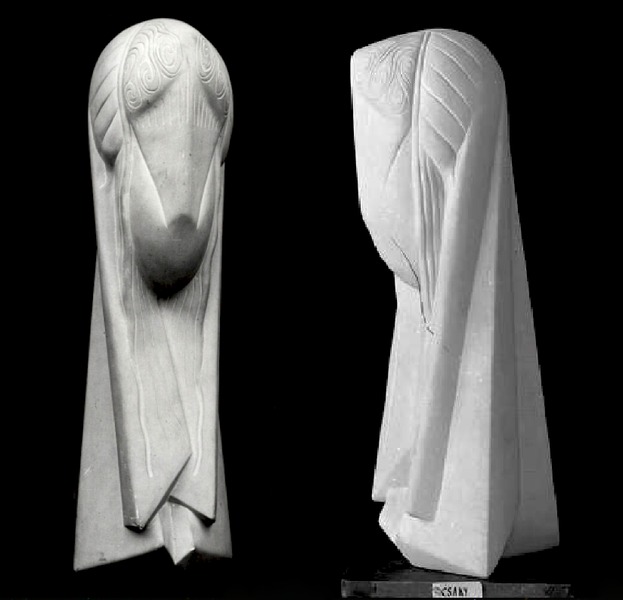

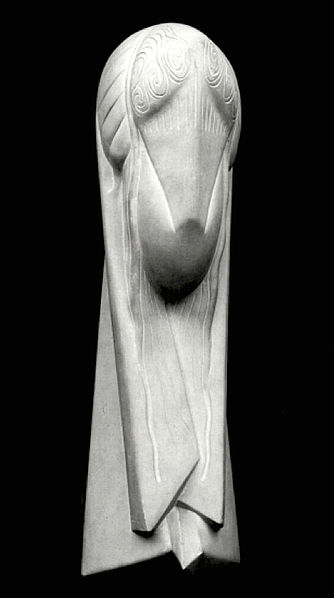

Csaky exhibited his highly stylized 1909 sculpture, Tęte de femme (Portrait de Jeanne), at the 1910 Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux - Arts. The following year, he exhibited a proto - Cubist work entitled Mademoiselle Douell (1910).

In 1911, Csaky exhibited his Cubist sculptures at the Salon des Indépendants (21 April - 13 June) with Archipenko, Duchamp, Gleizes, Laurencin, La Fresnaye, Léger, Picabia and Metzinger. This exhibition provoked an 'involuntary scandal' out of which Cubism, brought to the attention of the general public for the first time, emerged and spread throughout Paris and beyond. Four months later Csaky exhibited at the Salon d'Automne (1 October - 8 November) together with the same artists, in addition to Modigliani, Lhote, Duchamp - Villon, Villon and František Kupka.

The following year Csaky showed with the Cubists at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants (20 March - 16 May): with Archipenko, Gleizes, La Fresnaye, Laurencin, Le Fauconnier, Léger, Lhote, Zadkine, Duchamp, Constantin Brâncuşi, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Robert Delaunay, Juan Gris, Piet Mondrian, Alfréd Réth and Diego Rivera.

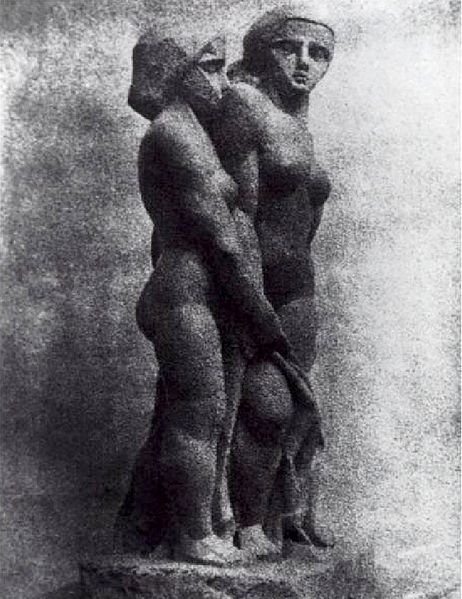

Csaky participated in the Salon d'Automne of 1912 (1 October - 8 November) with the Cubists: Duchamp, Duchamp - Villon, Gleizes, La Fresnaye, Le Fauconnier, Léger, Lhote, Marcoussis, Metzinger, Picabia, Villon and Kupka. A rare photograph of the 1912 Salon d'Automne shows Csaky's Groupe de femmes, a sculpture now lost, exhibited in front of Kupka's Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colours and next to sculptures by Amedeo Modigliani. In the same photograph can be seen Henri Le Fauconnier's vast composition Les Montagnards attaqués par des ours (Mountaineers Attacked by Bears,) now at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum; and Francis Picabia's monumental La Source (The Spring), now at the Museum of Modern Art] in New York.

Csaky exhibited as a member of Section d’Or at the Galerie La Boétie (10-30 October 1912), with Archipenko, Duchamp - Villon, La Fresnaye, Gleizes, Gris, Laurencin, Léger, Lhote, Marcoussis, Metzinger, Picabia, Kupka, Villon and Duchamp.

By this time, Csaky's participation in the avant garde

milieu was complete.

"One could say that before the war, life in Paris had been like a summer day, and after the announcement of war the sky and life were darkened by weighty, heavy clouds" (Joseph Csaky)

Csaky enlisted as a volunteer in the French army and was

expecting to be called in. Before joining his company, he

married Marguerite Fétrié on 19 August 1914. She had

become pregnant and had a child during their relationship,

and Csaky wanted to become his daughter's legal father

prior to his departure for what became known as the Great War.

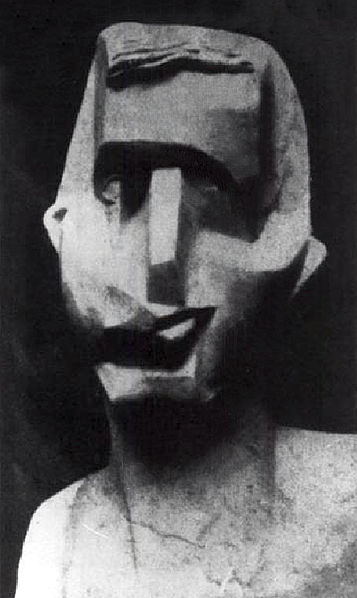

Returning to Paris after the war, Csaky began a series of works derived in part from the machine aesthetic; streamlined with geometric and mechanical affinities. By this time Csaky's artistic vocabulary had evolved: it was distinctly mature, showing a new, refined sculptural quality. Nothing in early modern sculpture in comparable to the revolutionary work Csaky produced in the years directly succeeding World War I. These were nonrepresentational free standing objects, i.e., abstract three - dimensional constructions combining organic and geometric elements.

- "Csaky derived from nature forms which were in concordance with his passion for architecture, simple, pure, and psychologically convincing." (Maurice Raynal, 1929)

The scholar Edith Balas writes of Csaky's sculpture following the war years:

"Csáky, more than anyone else working in sculpture, took Pierre Reverdy's theoretical writings on art and cubist doctrine to heart. "Cubism is an eminently plastic art; but an art of creation, not of reproduction and interpretation." The artist was to take no more than "elements" from the external world, and intuitively arrive at the "idea" of objects made up of what for him constant in value. Objects were not to be analyzed; neither were the experiences they evoked. They were to be re-created in the mind, and thereby purified. By some unexplained miracle the "pure" forms of the mind, an entirely autonomous vocabulary, of (usual geometric) forms, would make contact with the external world." (Balas, 1998)

These 1919 works (e.g., Cones and Spheres, Abstract Sculpture) are made of juxtaposing sequences of rhythmic geometric forms, where light and shadow, mass and the void, play a key role. They allude, occasionally, to the structure of the human body or modern machines, but the semblance functions only as "elements" (Reverdy) and are deprived of descriptive narrative. Csaky's polychrome reliefs of the early 1920s display an affinity with Purism — an extreme form of the Cubism aesthetic developing at the time — in their rigorous economy of architectonic symbols and the use of crystalline geometric structures.

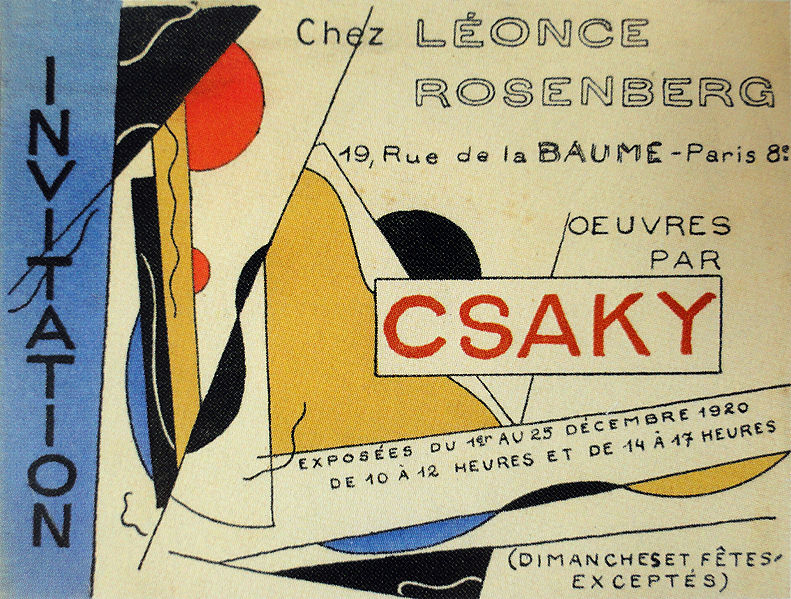

With this intense flurry of activity, Csaky was taken on by Léonce Rosenberg, owner of the Galerie l'Effort Moderne, 19, rue de la Baume, Paris. By 1920 Rosenberg was the sponsor, dealer and publisher of Piet Mondrian, Léger, Lipchitz and Csaky. He had just published Le Néo-Plasticisme — a collection of writings by Mondrian — and Theo van Doesburg's Classique - Baroque - Moderne. Csaky's showed a series of works at Rosenberg's gallery in December 1920.

For the following three years, Rosenberg purchased Csaky's entire artistic production. In 1921 Rosenberg organized an exhibit entitled Les maîtres du Cubisme, a group show that featured works by Csaky, Albert Gleizes, Metzinger, Mondrian, Gris, Léger, Picasso, Laurens, Georges Braque, Auguste Herbin, Gino Severini, Georges Valmier, Amédée Ozenfant and Léopold Survage.

Csaky's works of the early 1920s reflect a collective spirit of the time,

"a puritanical denial of sensuousness that reduced the cubist vocabulary to rectangles, verticals, horizontals," writes Balas, "a Spartan alliance of discipline and strength" to which Csaky adhered in his Tower Figures. "In their aesthetic order, lucidity, classical precision, emotional neutrality, and remoteness from visible reality, they should be considered stylistically and historically as belonging to the De Stijl movement." (Balas, 1998)

Joseph Csaky became a naturalized French citizen in 1922. He began to work with Marcel Coard, a dealer and gallery owner who from 1924 onward bought Csaky's sculptures in order to cast them in bronze. The two created furniture in the Art Deco style, within which sculpted elements of marble, wood and glass were integrated.

In 1927 Csaky collaborated with other artists, including

Gustave Miklos, Jacques Lipchitz and Louis Marcoussis, on

the decoration of Studio House, rue Saint - James,

Neuilly, owned by the French fashion designer Jacques

Doucet. Doucet was also collecting Post - Impressionist and Cubist paintings; he bought Les

Demoiselles d'Avignon directly from Picasso's

studio. Csaky designed the staircase in Studio House.

From 1928, while his fellow pioneers tended towards greater abstraction, Csaky moved away both from the faceted Cubism of his early Parisian epoch, and from the highly abstract or nonrepresentational intent of his post war series. Turning towards figurative art, he no longer saw potential in abstraction.

Waldemar George, the Polish-French art critic, writes in 1930 of Csaky's departure from abstraction: "The cube, the polyhedron with right angles with its abrupt edges, are replaced by ovoids and spheres." Turning towards a more representational figuration — in a highly stylized, curvilinear and descriptive form — allowed Csaky the contact with reality, a reality that ran deeper than surface appearances. For the rest of his life, he was interested primarily in the female body in youth, a theme that expressed optimism, happiness and well being. He was fascinated by the the beauty and expressiveness of the human form in itself. He explored the subject to express his ideas and connotations attached to them. His monumental figures (although not always in sheer size) possess a timeless "amaranthine beauty, a fundamental essence relevant only to themselves."

Csaky continued exhibiting from the 1930s onward; he was shown internationally, with shows in France, Germany, Holland, Brussels, Hungary, and Luxembourg. In 1935, he traveled in Greece, an experience that shaped his artistic exploration of nudes for the remainder of his life. He had an exhibit there in 1965.

Joseph Csaky died in Paris May 1, 1971.

Joseph Csaky contributed substantially to the development of modern sculpture, both as a pioneer in applying Cubism to sculpture, and as a leading figure in nonrepresentational art of the 1920s.

After fighting along side the French underground movement against the Nazis during World War II, Csaky faced many difficulties: health issues, family problems and a lack of work related commissions. Unlike many of his friends, whose names became widely known, Csaky was appreciated by fewer people (but they notably included art collectors, art historians and museum curators).

"Today, however," writes Edith Balas, "in a postmodernist atmosphere, those aspects of his art that made Csáky unacceptable to the more advanced modernists are readily accepted as valid and interesting. The time has come to give Csáky his rightful place in the ranks of the avant-garde, based on an analysis of his artistic innovations and accomplishments."