<Back to Index>

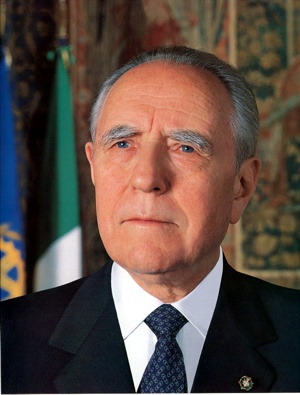

- 10th President of Italy Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, 1920

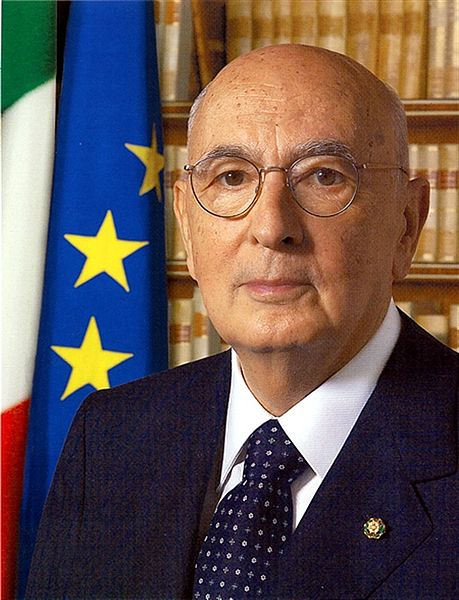

- 11th President of Italy Giorgio Napolitano, 1925

PAGE SPONSOR

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (December 9, 1920 - September 16, 2016) was an Italian politician, statesman and banker who was the prime minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994 and the president of Italy from 1999 to 2006.

Ciampi was born in Livorno. He received a B.A. in ancient Greek literature and classical philology in 1941 from the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, one of the country's most prestigious universities, defending a thesis, entitled Favorino d'Arelate e la consolazione Περὶ φυγῆς, under the direction of the Hellenist Augusto Mancini. Then he was called to military duty in Albania as a lieutenant. On 8 September 1943, on the date of the armistice with the Allies, he refused to remain in the Fascist Italian Social Republic, and took refuge in Abruzzo, in Scanno. He subsequently managed to pass the lines and reach Bari, where he joined the Partito d'Azione and thus the Italian resistance movement. In 1946 he married Franca Pilla. That same year, he obtained a B.A. in law from the University of Pisa and began working at the Banca d'Italia. He also joined the CGIL (Trade Union), which he left in 1980.

In 1960, he was called to work in the central administration of the Bank of Italy, where he became Secretary General in 1973, Vice Director General in 1976, and Director General in 1978. In October 1979, he was nominated Governor of the Bank of Italy and President of the national Bureau de Change, positions he filled until 1993.

Ciampi was the first non-parliamentarian prime minister of Italy in more than 100 years. From April 1993 to May 1994 he oversaw a technical government. Later, as treasury minister from 1996 to May 1999 in the governments of Romano Prodi and Massimo D'Alema, he was credited with adopting the euro currency. He chose the Italian design for the 1-euro coin, whereas all others were left to a television vote among some candidates the ministry had prepared. Ciampi chose the Vitruvian Man of Leonardo da Vinci, on the symbolic grounds that it represented man as a measure of all things, and in particular of the coin: in this perspective, money was at the service of man, instead of its opposite. The design also fitted very well on the bimetallic material of the coin.

According to the Italian weekly Famiglia Cristiana,

in 1993 Ciampi was a member of the regular Masonic Lodge "Hermes" of

Livorno which was affiliated to the Grand Orient of Italy

and linked to the Rito Filosofico Italiano.

Ciampi was elected with a broad majority, and was the second president ever to be elected at the first ballot (when there is a requirement of a two-thirds majority) in a joint session of the Chamber of Deputies, the Italian Senate and representatives of the Regions. He usually refrained from intervening directly into the political debate while serving as president. He often addressed general issues, without mentioning their connection to the current political debate, in order to state his opinion without being too intrusive. His interventions frequently stressed the need for all parties to respect the Constitution and observe the proprieties of political debate. He was generally held in high regard by all political forces represented in the parliament.

The possibility of persuading Ciampi to stand for a second term as president by the election 2006 - the so-called Ciampi-bis - was widely discussed, despite his advancing age, but it was officially dismissed by Ciampi himself on 3 May 2006: "None of the past nine presidents of the Republic has been re-elected. I think this has become a meaningful rule. It is better not to infringe it". Ciampi, whose mandate was due to expire on the 18th, resigned on the 15th. His successor, Giorgio Napolitano took the oath on the same day.

As head of state of the host country, he officially declared the 2006 Winter Olympics open, on 10 February 2006. As president, Ciampi was not considered to be close to the positions of the Vatican and the Catholic Church, in a sort of alternate after the devout Oscar Luigi Scalfaro. He often praised patriotism, not always a common feeling because of its abuse by the Italian Fascist regime.

He died in Rome on 16 September 2016 at the age of 95. His funeral was officiated at the Church of San Saturnino in Rome on 19 September by Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia. A national day of mourning was proclaimed on the same day and flags were flown at half mast.

Giorgio Napolitano (June 29, 1925 - September 22, 2023) was an Italian politician who served as the 11th president of Italy from 2006 to 2015, the first to be re-elected to the office. In office for 8 years and 244 days, he was the longest serving president, until the record was surpassed by Sergio Mattarella in 2023. He also was the longest lived president in the history of the Italian Republic, which has been in existence since 1946. Although he was a prominent figure of the First Italian Republic, he did not take part in the Constituent Assembly of Italy that drafted the Italian constitution; he is considered one of the symbols of the Second Italian Republic, which came about after the Tangentopoli scandal of the 1990s. Due to his dominant position in Italian politics, some critics have sometimes referred to him as Re Giorgio ("King Giorgio").

Napolitano was a longtime member of the Italian Communist Party, which he joined in 1945 after taking part in the Italian resistance movement, and of its post-Communist democratic socialist and social democratic successors, from the Democratic Party of the Left to the Democrats of the Left. He was a leading member of migliorismo, a reformist, moderate, and modernizing faction on the right wing of the PCI, which was inspired by the values of democratic socialism, looked favorably to social democracy, and was interested in revisionist Marxism. First elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1953, he took an assiduous interest in parliamentary life and was president of the Chamber of Deputies from 1992 to 1994. He was Minister of the Interior from 1996 to 1998 during the first Prodi government. A close friend of Henry Kissinger, he was also the first high ranking leader of a communist party to visit the United States, which he did in 1978.

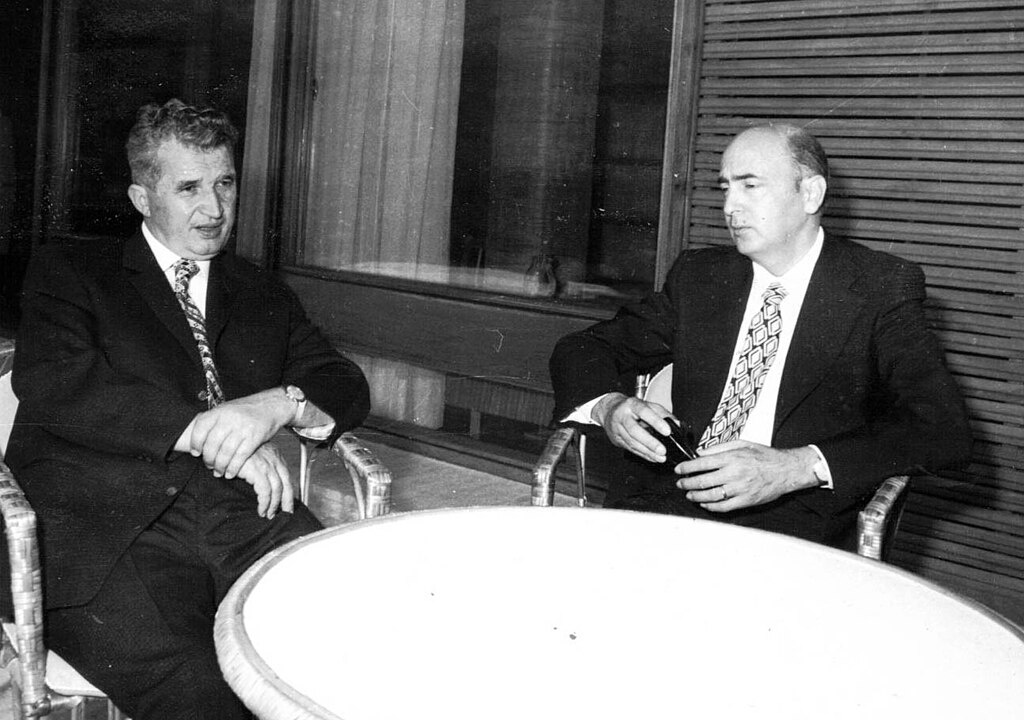

In 2005, Napolitano was appointed a senator for life in Italy by then president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi. In the May 2006 Italian presidential election, he was elected by the Italian Parliament as president of Italy. A pro-Europeanist, Napolitano was the first former Communist to hold said office. During his first term in office, he oversaw governments both of the center left coalition, such as the second Prodi government, and the center right coalition, such as the fourth Berlusconi government. In November 2011, Silvio Berlusconi resigned as prime minister of Italy amid financial and economic problems. In keeping with his constitutional role, Napolitano then asked former European commissioner Mario Monti to form a cabinet, which critics referred to as a "government of the president".

Napolitano intended to retire from politics after his seven-year presidential term expired, but reluctantly agreed to run again in the 2013 presidential election to safeguard the continuity of the country's institutions during the parliamentary deadlock that followed the February 2013 Italian general election. He was the first sitting president to run for a second term. On being re-elected as president with broad cross party support in Parliament, he overcame the impasse by inviting Enrico Letta to propose a grand coalition government. When Letta handed in his resignation in February 2014, Napolitano mandated Matteo Renzi (Letta's factional challenger) to form a new government. After a record eight and a half years as president, citing age factors, the 89 year old Napolitano resigned in January 2015. He had already stated that he did not intend to serve out a full second term. He then resumed his Italian Senate seat, which he held until his death in 2023.

Napolitano was often accused by his critics of having

transformed a largely ceremonial role into a political and

executive one, acting as kingmaker during his political

tenure. Supporters instead credited him with saving Italy

from the brink of default during the European debt crisis

and subsequent political stalemates, which helped to

stabilize the country. At the time of his

death in 2023, he was the longest-serving Italian

President as well as the longest lived Italian President

on record. He was also the oldest head of state in Europe

and the third oldest in the world, behind the Zimbabwean

president Robert Mugabe and Abdullah of Saudi Arabia. A

state funeral in secular form was held for Napolitano on

22 September 2023.

Napolitano was born in Naples, Campania, on 29 June 1925. His father Giovanni was a liberal lawyer and poet, while his mother was Carolina Bobbio, a descendant of a noble Piedmontese family. From 1938 to 1941, he studied at the Classical Lyceum Umberto I of Naples. In 1941, his family moved to Padua and he was graduated to the lyceum Titus Livius. In 1942, he matriculated at the University of Naples Federico II, studying law. During this period, Napolitano adhered to the local Fascist University Groups (Gruppi Universitari Fascisti), where he met his core group of friends, who shared his opposition to Italian fascism. As he would later state, the group "was in fact a true breeding ground of anti-fascist intellectual energies, disguised and to a certain extent tolerated".

An enthusiast of the theater since secondary school, during his university years he contributed a theatrical review to the IX Maggio weekly magazine and had small parts in plays organized by the Gioventł Universitaria Fascista itself. He played in a comedy by Salvatore Di Giacomo at Teatro Mercadante in Naples. Napolitano dreamed of being an actor and spent his early years performing in several productions at the Teatro Mercadante. He also loved reading the poetry of Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eugenio Montale, and Salvatore Quasimodo.

Napolitano has often been cited as the author of a collection of sonnets in Neapolitan dialect published under a pseudonym, Tommaso Pignatelli, and entitled Pe cupią 'o chiarfo ("To Mimic the Downpour"). He denied this in 1997 and on the occasion of his presidential election, when his staff described the attribution of authorship to Napolitano as a "journalistic myth". He published his first acknowledged book, entitled Movimento Operaio e Industria di Stato ("Workers' Movement and State Industry"), in 1962.

During the

existence of the Italian Social Republic (1943 - 1945), a

puppet state of Nazi Germany in the final period of World

War II, Napolitano and his circle of friends took part in

several actions of the Italian resistance movement against

German and Italian fascist

forces. In 1944, along with

the group of Neapolitan communists,

such as Mario Palermo and Maurizio Valenzi, Napolitano

prepared the arrival in Naples of Palmiro Togliatti, the long time

leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) who was in

exile since 1926 when the Communist

Party of Italy (PCd'I) was banned by the Fascist regime in Italy;

Togliatti was one of few leaders not to be arrested, as he

was attending a meeting of the Comintern

in Moscow. In 1945, Napolitano

joined the PCI.

Following the end of the war in 1945, Napolitano became the PCI's federal secretary for Naples and Caserta. In 1947, he graduated in jurisprudence with a final dissertation on political economy, entitled Il mancato sviluppo industriale del Mezzogiorno dopo l'unitą e la legge speciale per Napoli del 1904 ("The Lack of Industrial Development in the Mezzogiorno following the Unification of Italy and the Special Law of 1904 for Naples"). He became a member of the Secretariat of the Italian Economic Center for Southern Italy in 1946, which was represented by Giuseppe Paratore, where he remained for two years. Napolitano played a major role in the Movement for the Rebirth of Southern Italy for over ten years.

On 11 June 1946, nine days after the 1946 Italian institutional referendum in which Italy became a republic, Napolitano was at the headquarters of the Communist federation in via Medina when they were besieged for many hours by a crowd of royalist demonstrators who were enraged by the display of the party's red flag and the tricolor without the Savoy coat of arms. Many of them were impoverished people who, in the words of Napolitano years later, were "immersed in the context of a real social disintegration". They were animated by feelings of loyalty to the Savoy monarchy and by the ancient feeling of Southern Italy separatism, which had reawakened against Northern Italy, which had first wanted fascism and had imposed it on the South, and now wanted to impose the republic. About this event, which became known as the via Medina massacre, he later ruled out that it was only "the work of provocateurs, troublemakers, professional agitators and criminals".

In the 1953 Italian general election, Napolitano was first elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the electoral district of Naples. Apart from the 1963 Italian general election, when he did not seek re-election because he was the secretary of the Naples federation, a position he held from 1962 to 1966, he was always re-elected up to the 1996 Italian general election. He was elected to the National Committee of the party during its eighth national congress in 1956, largely thanks to the support offered by Togliatti, who wanted to involve younger politicians in the central direction of the party. He became responsible for the commission for Southern Italy within the National Committee.

A 26 May 1953 document of the Italian Ministry of the Interior reported Napolitano as a member of the secret armed paramilitary groups of the PCI in the city of Rome, what became known as Gladio Rossa. When the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and its military suppression by the Soviet Union (USSR) occurred, the leadership of the PCI labelled the insurgents as counter revolutionaries, and the official party newspaper L'Unitą referred to them as "thugs" and "despicable agents provocateurs". Napolitano complied with the party sponsored position on this matter, a choice for which he was later criticized; he repeatedly declared to have become uncomfortable with the decision, developing what his autobiography describes as a "grievous self critical torment". He would reason that his compliance was motivated by concerns about the role of the PCI as "inseparable from the fates of the socialist forces guided by the USSR" as opposed to imperialist forces.

The decision to support the Soviets against the Hungarian

revolutionaries generated a split in the PCI, and the CGIL (Italy's largest trade

union, then supportive of the PCI) refused to conform to

the party sponsored position and applauded the revolution,

on the basis that the eighth national congress of the PCI

had stated that the "Italian Way to Socialism" was to be

democratic and specific to the nation. These views were

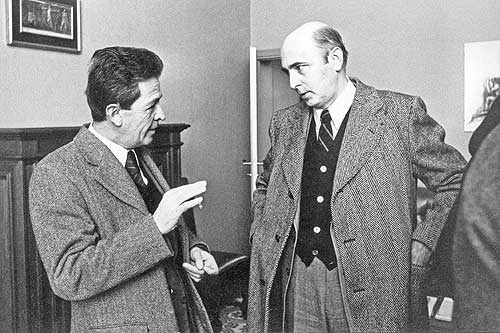

supported in the party by Giorgio Amendola, whom

Napolitano would always look up to as a teacher.

Frequently seen together, Amendola and Napolitano would

jokingly be referred to by friends as respectively Giorgio

'o chiatto and Giorgio 'o sicco ("Giorgio

the Pudgy" and "Giorgio the Slim" in the Neapolitan

dialect).

Between 1963 and 1966, Napolitano was party chairman in the city of Naples and later, between 1966 and 1969, he was appointed as chairman of the secretary's office and of the political office. In 1964, following the death of Togliatti, Napolitano was one of the main leaders who supported an alliance with the Italian Socialist Party, which after the end of the Popular Democratic Front joined the government with Christian Democracy. During the 1970s and 1980s, Napolitano was in charge for cultural activities, economic policy, and the international relations of the party.

Napolitano's political thought was somewhat moderate in the context of the PCI; he became the leader of the wing of the party called migliorismo, whose members notably included Gerardo Chiaromonte and Emanuele Macaluso. The term migliorista (from migliore, Italian for "better") was coined with a slightly mocking intent. To be a betterist was regarded more negatively than to be a reformist by traditional Communists. Their aim was to reform and improve, hence the name, capitalism by gradualist means. Henry Kissinger is said to have called Napolitano his "favorite Communist", while La Stampa described him as an atypical Communist, and once called him "the least communist Communist [sic] that the party ever enlisted". In 2015, Kissinger presented him the Henry A. Kissinger Prize, which is awarded by the American Academy in Berlin for exceptional contributions to transatlantic relations.

In the mid 1970s, Napolitano was invited by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to give a lecture; the United States ambassador to Italy, John A. Volpe, refused to grant Napolitano a visa on account of his membership of the PCI. Between 1977 and 1981, Napolitano had some secret meetings with the United States ambassador Richard N. Gardner, at a time when the PCI was seeking contact with the US administration, in the context of its definitive break with its past relationship with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the beginning of Eurocommunism, the attempt to develop a theory and practice more adapted to the democratic countries of Western Europe. He was an active member of the party until it ended in 1991. In 2006, when Napolitano was elected president of the Italian Republic, Gardner stated to the Associated Press Television News that he considered Napolitano "a real statesman", "a true believer in democracy", and "a friend of the United States [who] will carry out his office with impartiality and fairness".

Thanks to this role and in part by the good offices of Giulio Andreotti, in the 1980s Napolitano was able to travel to the United States and give lectures at Aspen, Colorado, and at Harvard University. He has since visited and lectured in the United States several times. After the death of Enrico Berlinguer in 1984, Napolitano was among the possible successors as secretary of the party; Alessandro Natta was elected instead, and it was the second time that he came close to the party's highest position, the first time being in 1972 when Berlinguer was favored over him. In July 1989, Napolitano became foreign minister in the PCI shadow government, from which he resigned the day after the Congress of Rimini, where the PCI was dissolved. That same year, Napolitano supported the motion that led to the PCI's transformation and name change.

After the dissolution of the PCI in February 1991, Napolitano followed most of its membership into the Democratic Party of the Left, a democratic socialist and social democratic party, which is considered the post Communist evolution of the PCI.

In 1992,

Napolitano was elected president of the Chamber of

Deputies, replacing Oscar Luigi Scalfaro, who became

president of the Italian Republic. That legislature was

hit by Tangentopoli

and his presidency became one of the fronts of the

relationship between the judiciary and politics. He was a

prominent symbol of the Second

Italian Republic that ensued.

After the 1996 Italian general election, the Italian center left Prime Minister Romano Prodi selected him as Minister of the Interior. He was the first former Communist to hold the office, a role traditionally occupied by Christian Democrats. In this capacity, he took part, together with fellow lawmaker and cabinet minister Livia Turco, in drafting the government sponsored law on immigration control (Law No. 40 of 6 March 1998), which is better known as the Turco - Napolitano Act. This bill was partially reformed by the third Berlusconi government in 2002 with the Bossi - Fini Act.

Napolitano remained Minister of the Interior until

October 1998, when Prodi's government lost its majority in

the Italian Parliament. He also served a second term as a

member of the European Parliament from 1999 to 2004 within

the Party of European Socialists, and was part of the

European Parliament Committee on Constitutional Affairs. In October 2005,

Napolitano was named senator for life, and was one of the

last two to be appointed by Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, the then

Italian president of the Republic, together with Sergio

Pininfarina.

The 2006 Italian general election saw a victory of Prodi, Italy's center left coalition candidate, against the incumbent Italian center right Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. After the election, the presidents of both houses of Parliament were chosen by the winning center left coalition, and so the center right House of Freedoms demanded an impartial candidate for the role of president of the Italian Republic. The Union stressed the fact that the Italian constitution demands that the president be a defender of the constitution, hinting that such a quality was scarce among the opposition members. Berlusconi complained about Napolitano's over fifty year Communist militancy, reiterated his allegations of election fraud, and said that "there is a fake majority that with a 24 thousand vote difference in just one month has occupied the government, presidency of the Chamber, the Senate and the Republic!"

In line with the anti-communist stance he had taken in the campaign, Berlusconi was the most vocal opponent of any candidate that came from the PCI. His allies, especially the Union of Christian and Center Democrats (UDC), openly disagreed with his intransigence but vowed to stick with their ally's decision. When Napolitano was elected, Berlusconi gave an interview to Panorama, one of his political magazines, saying that the UDC betrayed him by letting 60 of his electors cast a blank vote on the first ballot, instead of supporting the official candidate Gianni Letta. When the UDC argued that this might have spelt the end of the coalition, Berlusconi changed his stance by saying that he had been misunderstood and that he never gave that journalist an interview.

The candidacy of Massimo D'Alema was supported by Napolitano's party, the Democrats of the Left, and by other parties of the coalition, such as the Party of Italian Communists, the Communist Refoundation Party, and Democracy is Freedom - The Daisy; it was opposed by others, such as the Rose in the Fist, arguing that his candidacy was driven by a particracy's mentality. Part of the more left wing coalition considered D'Alema far too willing to conduct backroom deals with the opposition. Some moderate journalists liked D'Alema because his presidency would have given Prodi a stable government since the biggest party of the Union had not been rewarded with any institutional position. Initially, it was also thought that the incumbent president Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, who nominated Napolitano senator for life in 2005, could be re-elected, being favored by the center right coalition over D'Alema; Ciampi refused, and the front runner soon became D'Alema.

In the opposition coalition, while Berlusconi vehemently opposed a D'Alema presidency, some of his aides, such as Mediaset president Fedele Confalonieri and Marcello Dell'Utri, used the electoral fraud allegations as a means to get a president more favorable to Berlusconi saying that they were willing to move on from the electoral fraud allegations, and some right leaning newspapers, such as Il Foglio, campaigned for D'Alema. The official stance of the center right was that D'Alema, being an important left wing politician and having participated in the election campaign, was ill suited for president, a role that it is supposed to be impartial. When the Union proposed Napolitano, the House of Freedom objected that the Union should have presented a list of names. Even though Napolitano appeared at first a candidate that the House of Freedoms could converge on, the proposal was rejected much like that of D'Alema. On 5 May, Berlusconi had been unable to convince Gianfranco Fini of National Alliance to support D'Alema, while the Democrats of the Left explored the candidacy of Giuliano Amato and Emma Bonino before Piero Fassino and D'Alema, in agreement with Prodi, shifted to then 81 year old Napolitano.

On 7 May, the center left majority coalition officially endorsed Napolitano as its candidate in the 2006 Italian presidential election, which began on 8 May. The Holy See endorsed him as president through its official newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, just after the Union named him as its candidate, as did Marco Follini, former secretary of the UDC, a member party of the House of Freedoms. Napolitano was elected on 10 May, in the fourth round of voting - the first of those requiring only an absolute majority, unlike the first three which required two-thirds of the votes - with 543 votes (out of a possible 1,009). At the age of 80, he became the first former Communist to become president of Italy, as well as the third Neapolitan after Enrico De Nicola and Giovanni Leone. He came out of retirement to accept.

After Napolitano's election, expressions of esteem toward

him personally as regarding his authoritative character as

the future president of the Italian Republic were made by

both members of the Union and of the House of Freedoms,

which had turned in blank votes,

such as Pier Ferdinando Casini. Nevertheless, some Italian

right wing newspapers, such as il Giornale,

expressed concerns about his Communist past. He started his term

on 15 May. After his election, Berlusconi commented: "Best

wishes to Napolitano, nothing to complain about the

person, but now I hope that he will carry out his role

with true impartiality." Over the years,

Berlusconi changed his mind about Napolitano until he

refused to pardon him for his conviction in the Mediaset trial.

On 9 July 2006, Napolitano was present at the 2006 FIFA World Cup final, in which the Italy national team defeated France and won its fourth World Cup, and afterwards he joined the players' celebrations. He is the second president of the Italian Republic to be present at a FIFA World Cup final won by the Italian team after Sandro Pertini in 1982. On 26 September 2006, Napolitano made an official visit to Budapest, Hungary, where he paid tribute to the fallen in the 1956 revolution, which he initially opposed as member of the PCI, by laying a wreath at Imre Nagy's grave. On 10 February 2007, a diplomatic crisis arose between Italy and Croatia after Napolitano made an official speech during the celebration of the National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe. In the speech, he stated:

Already in the unleashing of the first wave of blind and extreme violence in those lands, in the autumn of 1943, summary and tumultuous justicialism, nationalist paroxysm, social retaliation and a plan to eradicate Italian presence intertwined in what was, and ceased to be, the Julian March. There was, therefore, a movement of hate and bloodthirsty fury, and a Slavic annexationist design, which prevailed above all in the peace treaty of 1947, and assumed the sinister shape of "ethnic cleansing". What we can say for sure is that what was consumed - in the most evident way through the inhuman ferocity of the foibe - was one of the barbarities of the past century.

The European Commission did not comment on this event but partly condemned the response by Croatian president Stjepan Mesić, who described Napolitano's statement as racist because Napolitano did not refer to either Slovenians or Croatians as a nation when he spoke about a "Slavic annexationist design" for the Julian March; at the time, Slovenians and Croatians fought together with the Yugoslav Partisans. Another matter of debate in Croatia was that Napolitano made awards to relatives of 25 foibe victims, who included the last fascist Italian prefect in Zadar, Vincenzo Serrentino, who was sentenced to death in 1947 in ibenik. That was seen by Mesić as historical revisionism and open support for revanchism. Napolitano's remarks on the foibe massacres were praised by both center left and center right in Italy, and both coalitions condemned Mesić's statements, while the whole of Croatia stood by Mesić, who later acknowledged that Napolitano did not want to put in discussion the Peace Treaty of 1947, saying that it is "absolutely unacceptable".

On 21 February 2007, Prodi submitted his resignation after losing a foreign policy vote in Parliament; Napolitano held talks with the political groups in Parliament, and rejected the resignation on 24 February, prompting Prodi to ask for a new vote of confidence. Prodi's cabinet remained in office after he won the vote in the upper house on 28 February, and then in the lower house on 2 March.

On 24 January 2008,

Prodi lost a vote of confidence in the Senate of the

Republic by a vote of 161 to 156 votes, after the Union of

Democrats for Europe ended its support for the Prodi led

government. On 30 January, Napolitano appointed the

president of the Senate Franco Marini to try to form a

caretaker government with the goal of changing the current

electoral system rather than call a quick election.

The state of the Italian electoral law of 2005 had been under criticism not only within the outgoing government but also among the opposition and in the general population because of the impossibility to choose candidates directly and of the risks that a close call election might not grant a stable majority in the Senate. After Marini was given the mandate, Bruno Tabacci and Mario Baccini splintered from the Union of Christian and Centre Democrats to form the White Rose, while Ferdinando Adornato and Angelo Sanza (two leading members of the Forza Italia faction Liberal - Popular Union) switched allegiance to the UDC. On 4 February, the Liberal Populars (a UDC faction that favoured merging with Forza Italia) seceded from UDC to join Berlusconi's People of Freedom later this year. That same day, Marini acknowledged that he had failed to find the necessary majority for an interim government.

After having met with all major political forces and having found opposition to forming an interim government mainly from centre-right coalition parties, such as Forza Italia and National Alliance, that were favoured in a possible next election and strongly in favour of an early vote, Marini resigned his mandate. Napolitano summoned Fausto Bertinotti and Marini, the two speakers of the houses of Parliament, acknowledging the end of the legislature on 5 February. He dissolved the Italian Parliament on 6 February. The ensuing snap election was held on 13 and 14 April 2008, together with the 2008 Italian local elections. The elections resulted in a decisive victory for Berlusconi's center right coalition.

On 7 May, Napolitano appointed Berlusconi as Prime Minister of Italy following his landslide victory in the 2008 Italian general election. The cabinet was officially inaugurated one day later, with Berlusconi thus becoming the second of five prime ministers in nine years under Napolitano. During the ensuing Belusconi government, Napolitano was at times criticized by the parliamentary opposition for having signed some of the laws approved by Parliament on the government's proposal, which were view critically by part of the opposition, particularly Antonio Di Pietro, who evaluated the possibility of an impeachment motion of Napolitano after he had signed a government decree - law for the readmission of the excluded Berlusconi's party lists in Lazio and Lombardy a few weeks before the 2010 Italian regional elections.

On 6 February 2009,

Napolitano refused to sign an emergency decree made by the

Berlusconi government in order to suspend a final court

sentence allowing suspension of nutrition to 38 year old

coma patient Eluana Englaro; the decree could not be

enacted by Berlusconi. This caused a major political

debate within Italy regarding the relationship between

Napolitano and the government in office.

In July 2011, Napolitano was Italy's most popular politician, with an 80% popularity rating compared to Berlusconi's 30% rating as prime minister. Citing Giuseppe Mazzini's "We Have No Flag" speech of 1844, he appealed to the regions of Italy to resolve the country's crisis. On 11 October, the Chamber of Deputies rejected the law on the budget of the state proposed by the government. As a result of this event, Berlusconi moved for a confidence vote in the Chamber of Deputies on 14 October; he won the vote with just 316 votes to 310, the minimum required to retain a majority. An increasing number of deputies continued to cross the floor and join the opposition. On 8 November, the Chamber of Deputies approved the law on the budget of the state that was previously rejected but with only 308 votes, while opposition parties did not participate in the vote to highlight that Berlusconi had lost his majority. After the vote, Berlusconi announced his resignation after Parliament passed economic reforms, as the bid - ask spread almost reached 600 points.

On 12 November, after a final meeting with his cabinet, Berlusconi met Napolitano at the Quirinal Palace to tend his resignation, which Napolitano accepted, in what was described as an end of an era, Berlusconi being Italy's longest serving post war prime minister, and his 17 year premiership in total marred by many scandals. This event was met with jeering and celebrations. As Berlusconi arrived at the presidential residence, a hostile crowd gathered with banners shouting insults at Berlusconi and throwing coins at the car. After his resignation, the booing and jeering continued as he left in his convoy, with the public shouting words like buffoon, dictator and mafioso.

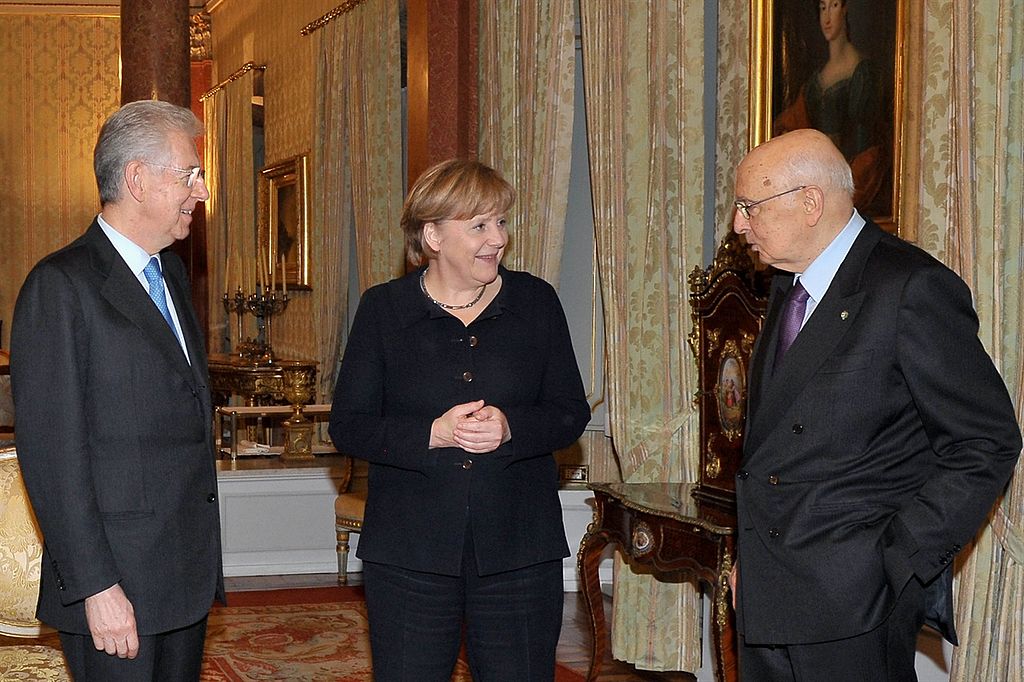

Following Berlusconi's resignation, Napolitano decided to appoint former European commissioner Mario Monti as a senator for life, and then as Prime Minister designate. The Monti Cabinet was subsequently confirmed by an overwhelming majority of both houses of Parliament in what was a technocratic cabinet, which was widely referred to as a "government of the president". He also earned the nickname "King George" (re Giorgio), which The New York Times attributed to "his stately defense of Italian democratic institutions". Napolitano's management of the events led to widespread international attention in his capacity as president, a role normally regarded as largely ceremonial. He received complimentary calls from multiple world leaders, including by the United States under Barack Obama, with whom he had positive relations. In December 2011, L'Espresso declared 2011 to be the year of Napolitano and named him the man of the year. While also used affectionately, the "King George" moniker was seen negatively by his critics on the Italian right, as they alleged that he had helped engineer the end of Berlusconi's final government after colluding with European Union authorities.

Monti later said that, due to Napolitano's role, he had

achieved the largest parliamentary majority and argued

that he did not fuel populism. He said that in 2013 he was

implored by the governing parties to remain as prime

minister. Critics accused

Napolitano of orchestrating a coup against Berlusconi, and

that he did this to help his former comrades; in fact,

many people in the Quirinale told Casini that Berlusconi

himself felt relieved, Berlusconi's party was instrumental

to the Monti government formation, and Berlusconi himself

supported Napolitano's re-election in 2013. According to

Casini, the coup story helped the center right coalition's

electoral campaign, with the center left coalition

suffering the most for their support of Monti even though

they had everything to gain from new elections. At

Napolitano's funeral in 2023, Gianni Letta dismissed the conspiracy theories related

to the alleged 2011 coup against Belusconi.

In February 2013, Napolitano wrote for L'Osservatore Romano. About the Fall of Communism, he spoke of the "overthrow of that revolutionary utopia which contained within itself promises of social emancipation and human liberation and which had ended up - as Norberto Bobbio said with a withering expression - by being overturned, in the conversion of done in its opposite." At the same time, he said that "the conservative ideology survived the end of Communism, increasingly taking on the appearance of that 'market fundamentalism', translated into deregulation and the abdication of politics, which only the global financial crisis which broke out in 2008 would have called into question."

Following five inconclusive ballots for the April 2013 Italian presidential election, Napolitano accepted to be re-elected as president - an unprecedented move - following pleas by Monti and the leaders of the main political blocks, Pier Luigi Bersani and Berlusconi. Napolitano reluctantly agreed to serve for another term in order to safeguard the continuity of the country's institutions. Napolitano was easily re-elected on 20 April, receiving 738 of the 1,007 possible votes, and was sworn in on 22 April after a speech when he asked for constitutional and electoral reforms. The critical findings on Porcellum (the Italian electoral law of 2005) echoed the words that Napolitano gave on 22 April before the Electoral College that had re-elected him for a second term.

After his

re-election, Napolitano immediately began consultations

with the chairmen of the Chamber of Deputies, Senate, and

political forces after the failure of the previous attempt

with Bersani after the inconclusive February 2013 Italian general

election, and the establishment of a panel of ten

experts by Napolitano himself, who were dubbed as wise men

by the press, in order to outline

priorities and formulate an agenda to deal with the

persistent economic hardship and growing unemployment and

end the country's political deadlock, as well as to

nominate his successor.

On 24 April, Napolitano gave to the vice-secretary of the center left Democratic Party, Enrico Letta, the task of forming a government, having determined that Bersani, leader of the winning coalition Italy Common Good, could not form a government because it did not have a majority in the Senate. Bersani refused a coalition with Berlusconi's party and attempted to form a government with the anti - establishment Five Star Movement but failed in his bid.

On 27 April, Letta formally accepted the task of leading a grand coalition government, which was described as unprecedened, with support from the Democratic Party, of which he remained deputy secretary, the center right People of Freedom of Berlusconi, and the centrist Civic Choice of Monti, and subsequently listed the members of the Letta Cabinet. Napolitano described it as the "only government possible", and said: "I hope that this government can get to work quickly in the spirit of fervent co-operation and without any prejudice or conflict. It was and is the only possible government."

The government formed by Letta became the first in the history of the Italian Republic to include representatives of all the major candidate coalitions that had competed in the election, and included a record number of women. His close relationship with his uncle Gianni Letta, one of Berlusconi's most trusted advisors, was perceived as a way of overcoming the bitter hostility between the two opposing camps. Letta appointed Angelino Alfano, secretary of the People of Freedom, as his Deputy Prime Minister of Italy. Letta was formally sworn in as prime minister on 28 April; during the ceremony, a man fired shots outside Palazzo Chigi and wounded two Carabinieri.

On 30 January 2014, the Five Star Movement deposited an

impeachment motion,

which was criticized by the other parties and was later

dismissed by the impeachment committee, for six charges

accusing Napolitano of harming the Italian constitution,

to allow unconstitutional laws and in relation to the

State - Mafia Pact, which remained controversial after his

death in 2023.

In the 2013 Democratic Party leadership election, Matteo Renzi, the mayor of Florence, was elected with 68% of the popular vote, compared to 18% for Gianni Cuperlo, and 14% for Giuseppe Civati. He became the new secretary of the Democratic Party and the centre-left's prospective candidate for Prime Minister. His victory was welcomed by Letta, who had been the vice-secretary of the party under Bersani's leadership. In an earlier speech, Renzi had paid tribute to Letta, saying that he was not intended to put him "on trial". Without directly proposing himself as the next Prime Minister, he said the Eurozone's third largest economy urgently needed "a new phase" and "radical program" to push through badly needed reforms. The motion he put forward made clear "the necessity and urgency of opening a new phase with a new executive". Speaking privately to party leaders, Renzi said that Italy was "at a crossroads" and faced either holding fresh elections or a new government without a return to the polls.

On 13 February, Letta dismissed rumours of his resignation. On 14 February, Napolitano accepted Letta's resignation from the office of Prime Minister; Napolitano wanted to avoid new elections until changes were made to Italy's electoral law, which many blamed for producing the deadlock and stalemate of Italian politics during those years; he said that he wanted to resolve the political crisis "as quickly as possible" so that a new government in what he described as "this fragile economic phase" could pass a new electoral law and institutional reforms. Following Letta's resignation, Renzi formally received the task of forming the new Italian government from Napolitano on 17 February. Renzi held several days of talks with party leaders, all of which he broadcast live on the internet, before unveiling his Cabinet on 21 February, which contained members of the Democratic Party, the New Center Right, the Union of the Center, and the Civic Choice. His cabinet became Italy's youngest government to date, with an average age of 47. It was also the first in which the number of female ministers was equal to the number of male ministers, excluding the Prime Minister. On 22 February, Renzi was formally sworn in as prime minister, becoming the fourth prime minister in four years and the youngest prime minister in the history of Italy, and the Renzi Cabinet was established.

On 9 November 2014,

the Italian press reported that Napolitano would step down

at the end of the year.

The press office of the Quirinal Palace "neither confirmed

nor denied" the reports. Citing age reasons, Napolitano

officially resigned on 14 January 2015 after the end of

the six month Italian presidency of the European Union.

After the presidency, Napolitano once again became senator for life in Italy after the end of his presidency on 14 January 2015. On 19 January, he joined the For the Autonomies group in the Senate. On 23 and 24 March 2018, he was the provisional president of the Senate as the most senior senator during the election of the new president of the Senate in the 18th legislature of the Italian Republic.

Napolitano had surgery on his aorta in April 2018, and was in the intensive care unit after abdominal surgery in May 2021. On 13 October 2022, on the occasion of the first session of the 19th legislature of the Italian Republic, he renounced to the role of provisional president of the Senate, which was taken by Liliana Segre.

At the beginning of

1959, Napolitano met Clio Maria Bittoni (1934 - 2024), who

had graduated in law. They were married at the town hall

in Rome a few months later in a civil ceremony. From the

marriage were born Giovanni (born 1961), who has two

children named Sofia and Simone,

and Giulio (born 1969).

Napolitano was a laico (secular layman) and non credente (non-believer), effectively an atheist. According to the Italian prelate of the Catholic Church and biblical scholar Gianfranco Ravasi, Napolitano always rejected the definition of either atheist or agnostic, which he did not like as formulas, and said that he was a non-believer, a layman who maintained close and positive relations with the Catholic Church and Pope Benedict XVI. During one of their first meetings, Napolitano quoted from Thomas Mann, one of his favourite writers, that "Christianity remains one of the pillars of the Western spirit and the other is the ancient Mediterranean culture."

Napolitano was the first to know about the pope's

resignation. Andrea Riccardi, founder of the Community of

Sant'Egidio and former minister in the Monti Cabinet, said

that "Napolitano considered the Church a component of

great importance in the social stability of the country"

and was concerned by the rightward shift of Catholics.

In 2023, Napolitano was hospitalized in Rome shortly after his 98th birthday on 29 June. On 19 September, he was reported to be in critical condition with his health deteriorating, and was taken off life support. He died three days later on 22 September at the age of 98. Italy's Council of Ministers proclaimed a day of national mourning and ordered flags to be flown half mast for five days in his honor.

Napolitano's state funeral was held on 26 September, and

was attended by international figures including four

incumbent presidents, one former president and over one

hundred ambassadors. In line with his personal views, it

was a secular funeral;

it was Italy's first funeral for a former president to be

held in this form. He was buried in

Rome's Cimitero Acattolico,

near other historical figures like Antonio Gramsci, Andrea

Camilleri, Emilio Lussu, Lindsay Kemp, Amelia Rosselli,

John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Napolitano is considered one of the most important figures of the Italian Republic, particularly of the Second Italian Republic between the 1990s and 2010s, and is described as a giant of Italian politics. He was the first Italian president to be re-elected, and was the first former Communist to achieve the Italian Republic's highest office. His life and career went almost through a century, being the longest-serving and longest lived president in the history of the Italian Republic. He underwent several changes, from supporting Soviet Communism from the 1940s to the 1960s, from the moderate transition in the 1960s and 1980s, and a man of the institutions from the 1990s to the 2010s. He is considered to have been a social democratic, pro-European, and reformist Communist; Le Monde described him as "a reformist Communist, capable of dialog with the leaders of the Christian Democrats and with the trade unions, a convinced pro-European, he participated in many international conferences in Europe, and formed ties with left wing leaders, such as Willy Brandt in Germany." Aldo Tortorella, another long time Communist member, described him as "a great left wing fighter".

The New York Times described him as the "Italian post Communist pillar". As president of Italy, Napolitano was charged by his critics of having transformed a largely ceremonial role into a political and executive one; he became the de facto kingmaker of Italian politics. In 2008 and 2011, he refused to hold snap elections and favored the formation of new governments instead to carry out reforms. This failed in 2008 when Berlusconi won the ensuing elections, while he succeeded in 2011 when he mandated Monti to form a government, a decision that remains controversial and polarizing but that it is considered to have saved Italy during the European debt crisis and praised for ending the country's political deadlock. In 2013, he accepted re-election reluctantly; before his resignation in 2015 due to age reasons, he again played a key role in forming Italy's first grand coalition government and ending the political stalemate.

Napolitano's death attracted international attention and recognition. The German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung described Napolitano as being "highly appreciated at an international level", where he was considered "an impartial and reliable interlocutor", while Deutsche Welle said that he "helped guide Italy through the EU sovereign debt crisis". In Spain, El Paķs characterized him as a "convinced European and renowned statesman" who "helped bring his country out of a debt crisis in 2011". In France, Le Monde described him as a "tireless militant" who "played a leading role in Italian political life" and a "symbol of stability and political longevity" during his nine years as head of state, and underscored his evolution from the "Red Prince" to "King George". In the United States, The New York Times emphasized Napolitano's crucial role in stabilizing the country.